This is the second installment of my analysis of an air strike orchestrated by a Predator in Uruzgan province, Afghanistan on 21 February 2010; the first installment is here.

(4) Command and control?

What was happening in and around Khod was being followed not only by flight crews and image analysts in the continental United States but also by several Special Forces command posts or Operations Centers in Afghanistan. In ascending order these were:

(1) the base from which ODA 3124 had set out at Firebase Tinsley (formerly known as Cobra);

(2) Special Operations Task Force-12 (SOTF-12), based at Kandahar;

(3) Combined Joint Special Operations Task Force – Afghanistan (CJSOTF-A) based at Bagram.

Once the ODA 3124 left the wire, command and support passed to SOTF-12; the OD-B at Tinsley had limited resources and limited (and as it happens intermittent) communications access and could only monitor what was happening.

That was normal, but in fact both higher commands did more or less the same: and the investigating team was clearly appalled. At SOTF-12 all senior (field grade) officers were asleep during the period of ‘highest density of risk and threatening kinetic activity’ (although they had established ‘wake-up criteria’ for emergency situations). The Night Battle Captain had been in post for just three weeks and had been given little training in his role; he received a stream of SALT reports from the Ground Force Commander of ODA 3124 (which detailed Size of enemy force, Activity of enemy force, Location and Time of observation) but simply monitored the developing situation – what one investigating officer characterised as ‘a pretty passive kind of watching’.

The same was true at CJSOTF-A (the staff there monitored 15-25 missions a day, but this was the only active operation that had declared a potential Troops in Contact).

When the more experienced Day Battle Captain entered the Joint Operations Center at Kandahar and was briefed by the Night Battle Captain he was sufficiently concerned to send a runner to ask the Judge Advocate, a military lawyer, to come to the JOC. He believed the occupants of the vehicles were hostile but was not convinced that they posed an immediate threat to troops on the ground: ‘I wanted to hear someone who was extremely smart with the tactical directive and use of CAS [Close Air Support] in a situation I hadn’t seen before’.

This was a smart call for many reasons; the commander of US Special Forces, Brigadier General Edward Reeder, told the inquiry: ‘Honestly I don’t take a shit without one [a JAG], especially in this business’. Significantly, the Safety Observer at Creech testified that there was no ‘operational law attorney’ available onsite for aircrews conducting remote operations; conversely, JAGs were on the operations floor of CENTCOM’s Combined Air and Space Operations Centre at Ul Udeid Air Base and, as this case shows, they were available at operations centers established by subordinate commands in-theatre.

The JAG at Kandahar was not routinely called in for ‘Troops in Contact’ but on this occasion he was told ‘my Legal Opinion [was] needed at the OPCENT and that it wasn’t imminent but they wanted me to rush over there right away…’

Meanwhile up at Bagram Colonel Gus Benton, the commanding officer of CJSOTF-A, was being briefed by his second-in-command who understood that the Ground Force Commander’s intention was to allow the three vehicles to move closer to his position at Khod. He thought that made sound tactical sense.

‘I said that … is what we did, we let them come to us so we can get eyes on them. During my time I never let my guys engage with CAS if they couldn’t see it. I said that is great and COL [Benton] said “that is not fucking great” and left the room.’

At 0820, ten minutes after the JAG entered the JOC at Kandahar, while he was watching the Predator feed, the phone rang: it was Benton. He demanded Lt Colonel Brian Petit, the SOTF-12 commander, be woken up and brought to the phone:

He spectacularly mis-read the situation (not least because he mis-read the Predator feed). It was true that the vehicles were in open country, and not near any compounds or villages; but Benton consistently claimed that the vehicles were ‘travelling towards our objective’ whereas – as MG McHale’s investigating team pointed out to him – they were in fact moving away from Khod.

There had also been some, inconclusive discussion of a possible ‘High Value Target’ when the vehicles were first tracked, but the presence of a pre-approved target on the Joint Prioritised Effects List (Benton’s ‘JPEL moving along this road’) had never been confirmed and the Ground Force Commander had effectively discarded it (‘above my authority’, he said).

Certainly, the JAG at Kandahar read the situation differently:

When Benton rang off, the JAG went over to the Day Battle Captain and Lt Col Petit and recommended an Aerial Vehicle Interdiction (AVI) team be called in for a show of force to stop the vehicles without engaging the occupants in offensive action.

They agreed; in fact another Task Force also watching the Predator feed called to make the same suggestion, and the Fires Officer set about arranging to use their Apache helicopters to conduct an AVI:

The Fires Officer had been responsible for setting up the Restricted Operating Zone for aircraft supporting the ODA – de-conflicting the airspace and establishing what aircraft would be available – but its management was de-centralised:

‘I establish the ROZ, give the initial layout of what assets are going on, and then I pass that to the JTAC [Joint Terminal Attack Controller with the Ground Force Commander at Khod]. I pass the frequencies to the assets and the JTAC controls them from there.’

At 0630, long before all this frantic activity at Kandahar, the two OH-58s had arrived at a short hold location beyond the ‘range of enemy visual and audio detection’, and at 0730 they had left to refuel at Tarin Kowt. The Day Battle Captain and the Fires Officer both thought they were still off station. In fact, the helicopters had returned to hold at Tinsley/Cobra at 0810 and flat pitched to conserve fuel (which means they landed and left the rotor blades spinning but with no lift); thirty minutes later the JTAC called them forward and the Predator began to talk them on to the target.

The Day Battle Captain had another reason for thinking he and his colleagues in the JOC had more time. He maintained that the helicopters had been brought in not to engage the three vehicles but to provide air support if and when the ‘convoy’ reached Khod and the precautionary ‘AirTic’ turned into a real TIC or Troops in Contact:

‘… the CAS brought on station for his [the Ground Force Commander’s] use was not for the vehicles but for what we thought was going to be a large TIC on the objective. The weapons team that was pushed forward to his location was not for the vehicles, it was for the possibility of a large TIC on the objective based on the ICOM chatter that we had.’

That chimes with Benton’s second-in-command at Bagram, who also thought the Ground Force Commander was waiting for the ‘convoy’ to reach Khod, but neither witness explained the basis for their belief. It was presumably a string of transmissions from the JTAC to the Predator crew: at 0538 he told them the Ground Force Commander wanted to ‘keep tracking them and bring them in as close as we can until we have CCA up’ (referring to the Close Combat Attack helicopters, the OH-58s); shortly before 0630 he confirmed that the Ground Force Commander’s intent was to ‘permit the enemy to close, and we’ll engage them closer when they’re all consolidated’; and at 0818 he was still talking about allowing the vehicles to ‘close distance.’

Yet this does not account for the evident urgency with which the Day Battle Captain and the JAG were concerned to establish ‘hostile intent’ and ‘immediate threat’. When the vehicles were first spotted they were 5 km from Khod, and when they were attacked they were 12 km away across broken and difficult terrain: so what was the rush if the Ground Force Commander was continuing to exercise what the Army calls ‘tactical patience’ and wait for the vehicles to reach him and his force?

In fact, the messages from the Ground Force Commander had been mixed; throughout the night the JTAC had also repeatedly made it clear that the ODA commander’s intent was ‘to destroy the vehicles and the personnel’. The Ground Force Commander insisted that ‘sometime between 0820 and 0830’ he sent a SALT report to SOTF-12 to say that he was going to engage the target. Unfortunately there is no way to confirm this, because SOTF’s text records of the verbal SALT reports stopped at 0630 for reasons that were never disclosed (or perhaps never pursued), but it would explain why the JTAC’s log apparently showed the JAG contacting him at 0829 to confirm there were no women and children on the target. It would also account for testimony by one of the screeners, who realised that the helicopters were cleared to engage at 0835, ten minutes before the strike, when the NCO responsible for monitoring the Predator feed at SOTF-12 ‘dropped’ into the ‘ISR’ (I presume the relevant chat room window), and in response:

‘The MC [Mission Intelligence Co-ordinator at Creech] passed that the OH58 were cleared to engage the vehicles. We were all caught off guard… It seemed strange because we had called out that these vehicles were going west. I don’t know how they determined these vehicles to be hostile… I brought up a whisper [private chat] with the MC, I said are you sure, what are the time frames when they will be coming in, and the MC responded saying we don’t know their ETA and at that moment the first vehicle blew up…’

Should those watching the events unfold have been taken aback when the vehicles were attacked? According to the pilot of the Predator, he and his crew were surprised at the rapid escalation of events:

‘The strike ultimately came a little quicker than we expected…. we believed we were going to continue to follow, continue to pass up feeds… When he decided to engage with the helos when they did, it happened very quickly from our standpoint. I don’t have a lot of info or situational awareness of why the JTAC decided to use them when they did. When they actually came up … the JTAC switched me on frequencies. So we weren’t talking on the frequency I was talking to him on a different frequency to coordinate with the helos.

But their surprise was as nothing compared to the reaction of most observers when the first vehicle exploded. The officer in charge of the screeners and imagery analysts who had been scrutinising the Predator feed at Air Force Special Operations Command at Hurlburt Field in Florida couldn’t believe it:

The Day Battle Captain testified:

‘I did not feel that the ground force commander would use any kind of close air support whatsoever to engage those vehicles… Based on the information that I had and looking at the vehicles move away it did not appear that they were moving towards the ground forces…

… as we were watching the Predator feed the first vehicles exploded. And everyone in the OPSCEN was immediately shocked… The amount of time from when that course of action approved by the SOTF commander to when we actually saw the strike occur there was no time, there was not adequate time to inform the ground commander that that was the course of action decided by the CJSOTF commander… I have phones ringing left and right, talking to people, trying to explain things, you know we look up on the screen and it happened…’

The Fires Officer:

‘I don’t think at any time anyone communicated to the GFC [Ground Force Commander] not to strike these vehicles because it is not something that we normally do. We feel that if he is in contact with the Predator and the OH-58s that we sent out to screen which we were not aware of and he is on the ground he generally has a pretty good picture of what is going on. He might be more privy to some conversation that he had with the OH-58 than what we know about. We normally give the GFC pretty big leeway on how they operate and the same with the JTAC because he has control of the assets and I am not going to try to take his assets away.’

In short, the investigation concluded that the Ground Force Commander never knew that an Aerial Vehicle Interdiction was being arranged, and neither of his higher commands were aware that he had cleared the helicopters to attack the three vehicles.

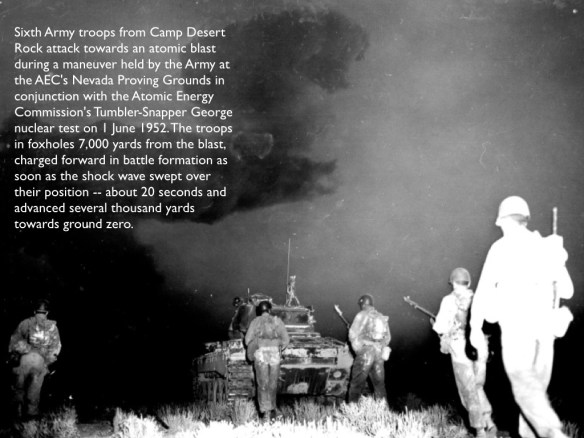

But, as I will show next, what lay behind these failures of communication was a de-centralised, distributed and dispersed geography of militarised vision whose fields of view expanded, contracted and even closed at different locations engaged in the administration of military violence. Far from being a concerted performance of Donna Haraway‘s ‘God-trick’ – the ability to see everything from nowhere – this version of networked war was one in which nobody had a clear and full view of what was happening.

Part of this can be attributed to technical issues – the different fields of view available on different platforms, the low resolution of infra-red imagery (which Andrew Cockburn claims registers a visual acuity of 20/200, ‘the legal definition of blindness in the United States’), transmission interruptions, and the compression of full-colour imagery to accommodate bandwidth pressure. So for example:

But it is also a matter of different interpretive fields. Peter Asaro cautions:

‘The fact that the members of this team all have access to high-resolution imagery of the same situation does not mean that they all ‘‘see’’ the same thing. The visual content and interpretation of the visual scene is the product of analysis and negotiation among the team, as well as the context given by the situational awareness, which is itself constructed.’

The point is a sharp one: different visualities jostle and collide, and in the transactions between the observers the possibility of any synoptic ‘God-trick’ disappears. But it needs to be sharpened, because different people have differential access to the distributed stream of visual feeds, mIRC and radio communications. Here the disposition of bodies combines with the techno-cultural capacity to make sense of what was happening to fracture any ‘common operating picture’. As one officer at Kandahar put it:

‘We didn’t have eyes on, minus ISR platform, that we can all see, who watches what? All the discrepancies between who watches what. What I see may be different from what someone else might interpret on the ISR… ISR is not reliable; it is simply a video platform.’

He was talking specifically about the multiple lines of communication (and hence bases for interpretation) within his Operations Center: now multiply that across sites scattered across Afghanistan and the continental United States and it becomes clear that the contemporary ‘fog of war’ may be as much the result of too much information as too little.

To be continued.