This is the fifth in a new series of posts on military violence against hospitals and medical personnel in conflict zones. It follows directly from my analysis of the situation in Syria here.

President Bashar al-Assad has consistently denied that his forces have attacked hospitals or doctors. In an interview with SBS Australia on 1 July 2016 he asked his interviewer:

‘… the very simple question is: why do we attack hospitals and civilians?… No government in this situation has any interest in killing civilians or attacking hospitals. Anyway, if you attack hospitals, you can use any building to be a hospital. No, these are anecdotal claims, mendacious statements …’

There are at least four answers to Assad’s disingenuous question (if you falter at the adjective, see here).

(1) Silencing the witnesses

When Widney Brown from Physicians for Human Rights testified at the Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission on 31 March 2016 she provided one clear and compelling rationale for Assad’s attacks on doctors:

‘… attacks on doctors silence particularly powerful witnesses. When the Syrian government denies its use of chemical weapons, cluster munitions, starvation, or torture, doctors can bear witnesses to these violations because they have seen and treated the victims.’

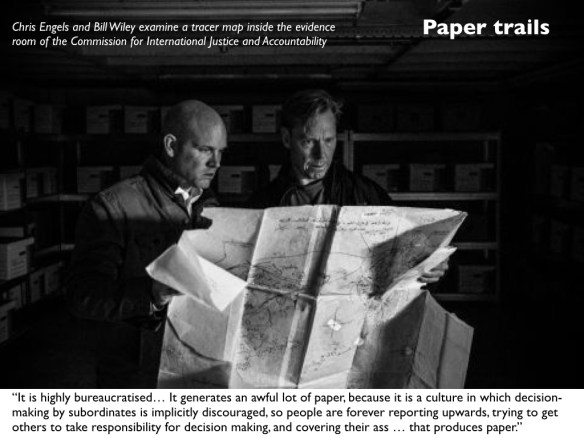

To be sure, there are other witnesses and even paper trails and photographic records. Ben Taub, who has done so much to bring ‘Syria’s war on doctors‘ to the attention of a wider public, has also provided a detailed account of the work done by Bill Wiley and the Commission for International Justice and Accountability whose volunteers have smuggled over 600,000 documents out of Syria detailing mass torture and killings by the regime.

The war crimes have not been confined to attacks on hospitals in opposition-held areas. A photographer known only as ‘Caesar’, who had been attached to the Defence Ministry’s Criminal Forensic Division, smuggled out thousands of high-resolution digital images exposing the horrors of the regime’s own military hospitals:

The pictures, most of them taken in Syrian military hospitals, show corpses photographed at close range – one at a time as well as in small groupings. Virtually all of the bodies – thousands of them – betray signs of torture: gouged eyes; mangled genitals; bruises and dried blood from beatings; acid and electric burns; emaciation; and marks from strangulation…

These unfortunates may have lived and died in different ways, but they were bound in death by coded numerals scribbled on their skin with markers, or on scraps of paper affixed to their bodies. The first set of numbers (for example, 2935 in the photographs at bottom) would denote a prisoner’s I.D. The second (for example, 215) would refer to the intelligence branch responsible for his or her death. Underneath these figures, in many cases, would appear the hospital case-file number (for example, 2487/B)…

[T]he system of organizing and recording the dead served three ends: to satisfy Syrian authorities that executions were carried out; to ensure that no one was improperly discharged; and to allow military judges to represent to families—by producing official-seeming death certificates—that their loved ones had died of natural causes. In many ways, these facilities were ideal for hiding “unwanted” individuals, alive or dead. As part of the Ministry of Defense, the hospitals were already fortified, which made it easy to shield their inner workings and keep away families who might come looking for missing relatives. “These hospitals provide cover for the crimes of the regime,” said Nawaf Fares, a top Syrian diplomat and tribal leader who defected in 2012. “People are brought into the hospitals, and killed, and their deaths are papered over with documentation.” When I asked him, during a recent interview in Dubai, Why involve the hospitals at all?, he leaned forward and said, “Because mass graves have a bad reputation.”

(2) Multiplying the casualties

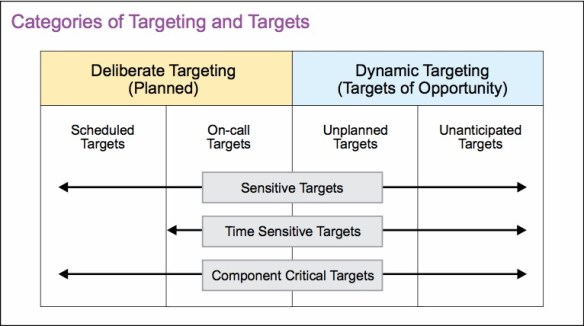

This is a radicalisation of an old strategy. As Sam Weber pointed out in Targets of opportunity (2005), ‘every target is inscribed in a network or chain of events that inevitably exceeds the opportunity that can be seized or the horizon that can be seen.’ So, for example, when the United States or Israel bombs a power plant it often as not explains that it has been careful to bomb in the small hours when only a skeleton staff was in the building in order to minimise collateral damage. But this begs the question: why bomb the power plant at all? In most instances the degradation of the electricity supply means that it becomes impossible to pump water or treat sewage; refrigerators fail and food perishes; hospitals are forced to use unreliable generators. The result – the intended, carefully calculated result – is that casualties rise at considerable distances from the target and over an extended period of time.

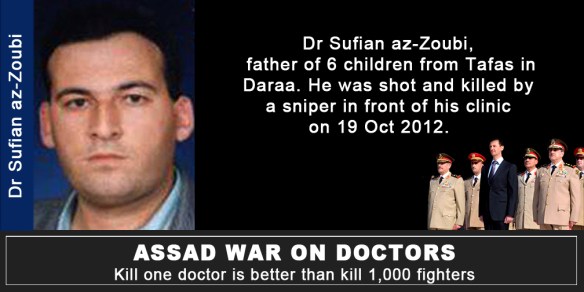

Similarly, Dr Abdulaziz Adel notes: ‘Kill a doctor and you kill thousands.’ Simply put, patients who are sick or injured then go without treatment and in many cases their lives are put at risk. (The images below are from Collateral Damage: more here).

Dr Rami Kalazi, a neurosurgeon from East Aleppo, agrees:

‘They are the artery of life in the city. Can you imagine a life in city without hospitals? Who will treat your kids? Who will make the surgeries for the injured people? So, they are targeting these hospitals because they know, if these hospitals were completely destroyed, the life will be completely destroyed.’

(3) ‘Moral[e] bombing’

This too is an old strategy. The architects of ‘area bombing’ during the combined bomber offensive against Germany during the Second World War described it as ‘moral [sic] bombing’: a sustained and systematic attempt to undermine the morale of the enemy population so that they would demand their leaders sue for peace. If this was a tried and tested strategy, however, the test showed that it was a complete failure (see my ‘Doors into nowhere’: DOWNLOADS tab).

But the lesson was lost in Syria, where attacks on hospitals have had a central place. As Samir Puri argues, the strategy behind the joint Syrian and Russian air campaign seems to be:

“If there is a total collapse of any kind of trauma care, those are the sort of things that can contribute to collapsing morale very suddenly. The morale of a besieged force can look robust until it collapses.”

And Syria is not unique in contemporary wars: Israel has deployed the same strategy in its repeated assaults on Gaza (see here, here and here for ‘Operation Protective Edge’ in 2014), and the Saudi-led coalition has attacked more than 70 hospitals and health facilities in Yemen since March 2015 (in this latter case Russian media have reported MSF’s objections to the ‘utter disregard for civilian life’ without dissent: see for example here).

‘Preventing medicine’, as Annie Sparrow puts it, has become ‘a new weapon of mass destruction’.

(4) ‘Violence legislates’

Following the attack on the UN aid convoy delivering supplies to a Syrian Red Crescent warehouse outside East Aleppo on 19 September 2016, 101 humanitarian organisations issued a joint appeal to the United Nations on 22 September; in part it read:

‘Deliberate attacks on humanitarian workers and civilians are war crimes. This must mark a turning point: the UN Security Council cannot allow increasingly brazen violations of international humanitarian law to continue with impunity.

‘Heads of state are gathered in New York this week for the United Nations General Assembly. Each one that accepts a lack of accountability for perpetrators and facilitators of war crimes colludes in the ongoing dissolution of international humanitarian law’ (my emphases).

The first paragraph is damning enough. Ben Taub in the New Yorker again:

Nowhere has the supposed deterrent of eventual justice proved so visibly ineffective as in Syria. Like most countries, Syria signed the Rome Statute, which, according to U.N. rules, means that it is bound by the “obligation not to defeat the object and purpose of the treaty.” But, because Syria never actually ratified the document, the International Criminal Court has no independent authority to investigate or prosecute crimes that take place within Syrian territory. The U.N. Security Council does have the power to refer jurisdiction to the court, but international criminal justice is a relatively new and fragile endeavor, and, to a disturbing extent, its application is contingent on geopolitics.

But the sting comes in the second paragraph. As I’ve noted before, international humanitarian law is not a neutral court of appeal, a deus ex machina above the fray, but has always been closely entangled with military violence. In many respects it travels in the baggage train, constantly pulled by the trajectory of the very violence it supposedly seeks to regulate (or facilitate, depending on your point of view). In short, as Eyal Weizman has it, ‘violence legislates‘.

There is good reason to fear that the systematic violation of medical neutrality is intended to force its dissolution. Thomas Arcaro writes: ‘Humanitarian principles like neutrality and impartiality that once seemed so self-evident have been drawn into question, especially on the politically and ethnically complex battlefields of Iraq and Syria.’

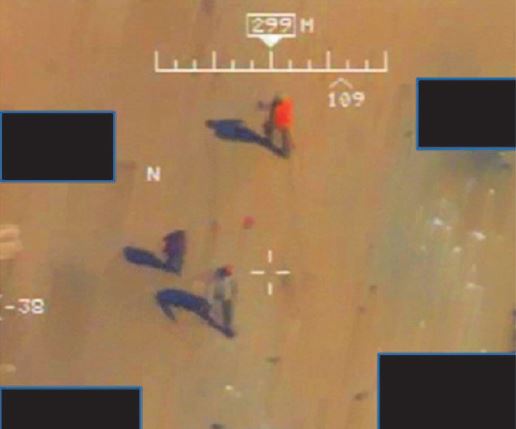

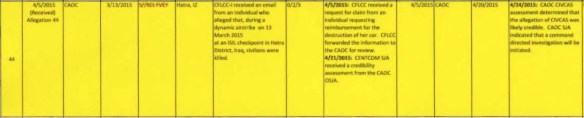

And not only there. In the case of the US airstrike on the MSF Trauma Centre in Kunduz in 2015, I’ve suggested that some key Afghan officers and politicians chafed at the protections afforded to wounded Taliban combatants by international humanitarian law. They also alleged that the Trauma Centre had breached its conditional immunity because the Taliban had overrun the hospital and were firing at US and Afghan forces from its precincts. There is no evidence to support that assertion, but it is an increasingly familiar claim. On 7 December 2016 US Central Command justified a ‘precision strike’ requested by Iraqi forces on a building within the al-Salem hospital complex in Mosul by claiming that IS fighters had used it as a base to launch heavy and sustained machine-gun and rocket-propelled grenade attacks. That would certainly have compromised the hospital’s immunity, but international humanitarian law still requires a warning to be issued before any attack and a proportionality analysis to be conducted; Colonel John Dorrian said that the US Air Force did not ‘have any reason to believe civilians were harmed’ but conceded that it was ‘very difficult to ascertain with full and total fidelity’ whether any medical staff or patients were in the building at the time of the air strike.

But what the Syrian case suggests is a new impatience with medical neutrality tout court: not only a hostility towards the treatment of wounded and sick combatants but also an unwillingness to extend sanctuary to wounded and sick civilians.

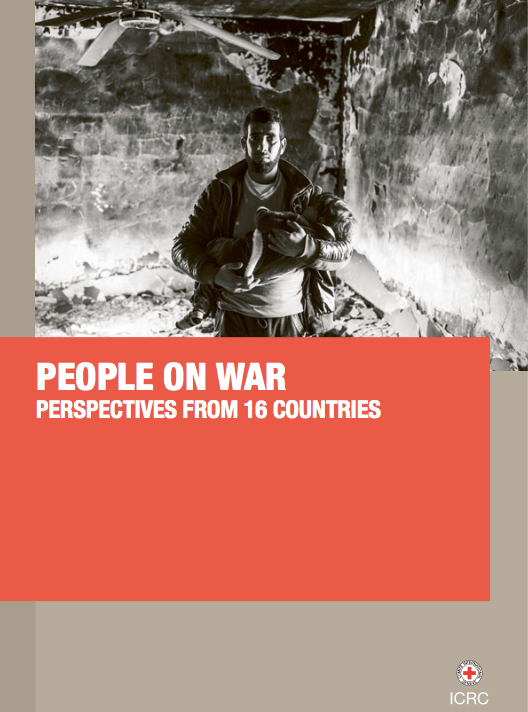

And that reluctance is not confined to the Assad regime and its allies. A survey carried out for the International Committee of the Red Cross between June and September makes for alarming reading – even once you’ve overcome your scepticism about public opinion polls. As Spencer Ackerman reports:

Areas in active conflict record greater urgency over questions of civilian protection in wartime than do the great powers that often conduct or participate in those conflicts. In Ukraine, 83% believe everyone wounded and sick during a conflict has a right to health care, compared with 62% of Russians. A full 100% of Yemenis endorse the proposition, as do 81% of Afghans, 66% of Syrians and 42% of Iraqis – compared with 49% of Americans, 53% of Britons, 37% of the Chinese and 67% of the French.

It’s that last clause that is so disturbing: for the last four states listed are all permanent members of the UN Security Council…

So what, then, are we to make of what I’ve been calling ‘the exception to the exception’?

The exception to the exception

I think it’s a mistake to treat ‘the camp’, following Giorgio Agamben‘s vital work, as the exemplary, diagnostic site of the modern space of exception; the killing fields of today’s wars (themselves spaces of indistinction, where it is never clear where war stops and peace begins, where the geometry of the battlefield or, better, ‘battlespace’ becomes ever more fractured and blurred, and where the partitions between international and internal conflicts have been reduced to rubble) are also spaces within which groups of people are deliberately and knowingly exposed to death through the removal of legal protections that would ordinarily be afforded to them. In short, killing and injuring become legally permissible.

I think it’s a mistake to treat ‘the camp’, following Giorgio Agamben‘s vital work, as the exemplary, diagnostic site of the modern space of exception; the killing fields of today’s wars (themselves spaces of indistinction, where it is never clear where war stops and peace begins, where the geometry of the battlefield or, better, ‘battlespace’ becomes ever more fractured and blurred, and where the partitions between international and internal conflicts have been reduced to rubble) are also spaces within which groups of people are deliberately and knowingly exposed to death through the removal of legal protections that would ordinarily be afforded to them. In short, killing and injuring become legally permissible.

Those exposed groups include both combatants and civilians, but their fate is not determined solely by the suspension of national laws (the case that concerns Agamben) because international humanitarian law continues to afford them some minimal protections. One of its central provisions has been medical neutrality: yet if, through its serial violations in Syria and elsewhere, we are witnessing the slow ‘death of the clinic’ – which I treat as a topological figure which extends from the body of the sick or wounded through the evacuation chain to the hospital itself – and the extinction of ‘the exception to the exception’, the clinic as a (conditionally) sacrosanct space – then I think it’s necessary to add further twists to Agamben’s original conception.

As Adia Benton and Sa’ed Ashtan have argued, medical neutrality – the exception to the exception – represents a fraught attempt to restrict the state’s recourse to military violence: it is a limitation on and has now perhaps become even an affront to sovereign power and the state’s insistence that it is ‘the sole arbiter of who can live and who can die’.

Agamben describes the inhabitants of the space of exception as so many homines sacri – where sacer has the double meaning of both ‘sacred’ and ‘accursed’ – and it may be that in today’s killing fields doctors, nurses and healthcare workers are being transformed into new versions of homo sacer: once ‘sacred’ for their selfless devotion to saving lives, they are now ‘accursed’ for their principled dedication to medical neutrality.

Yet the precarity of their existence under conditions of detention and torture, siege and airstrike, has not reduced them to what Agamben calls ‘bare life’. They care – desperately – whether they live or die; they have improvised a series of survival strategies; they have not been silent in the face of almost unspeakable horror; and they have developed new forms of solidarity, support and sociality.