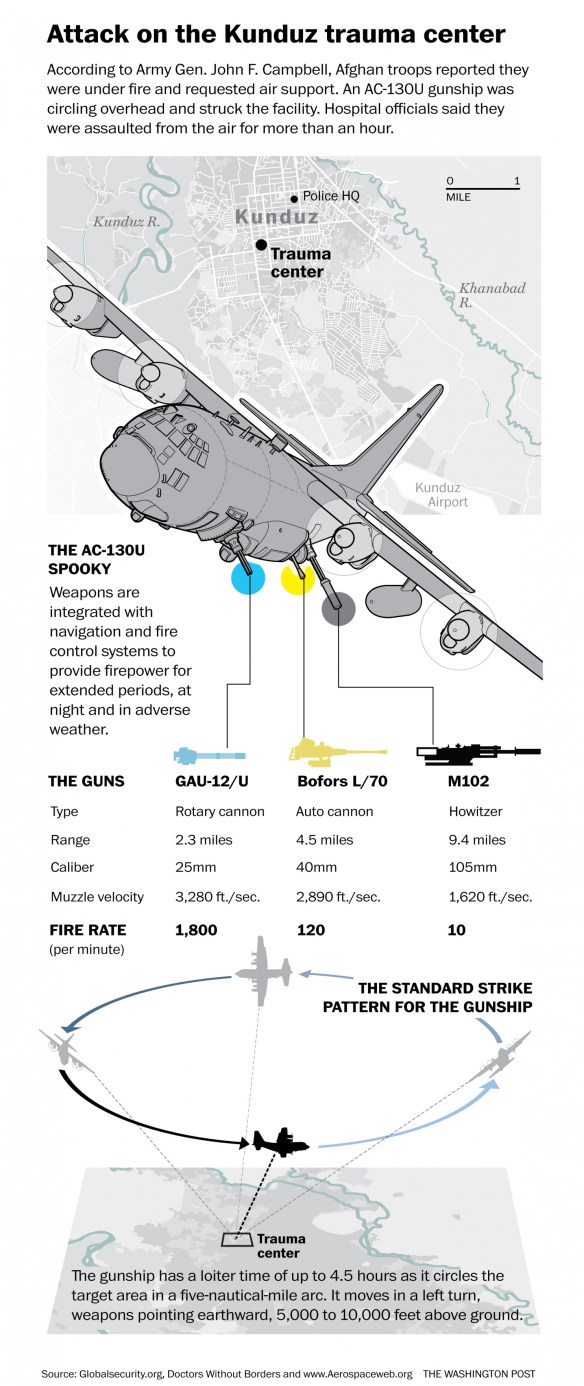

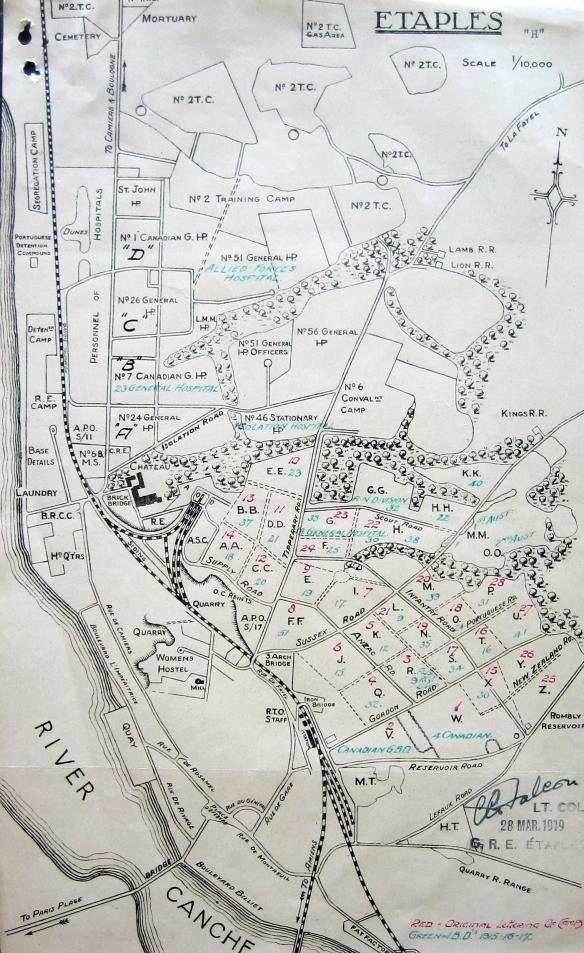

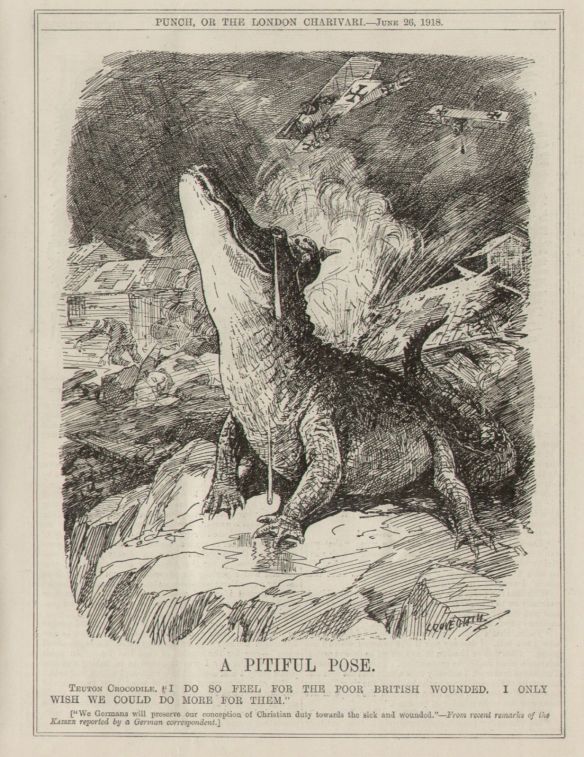

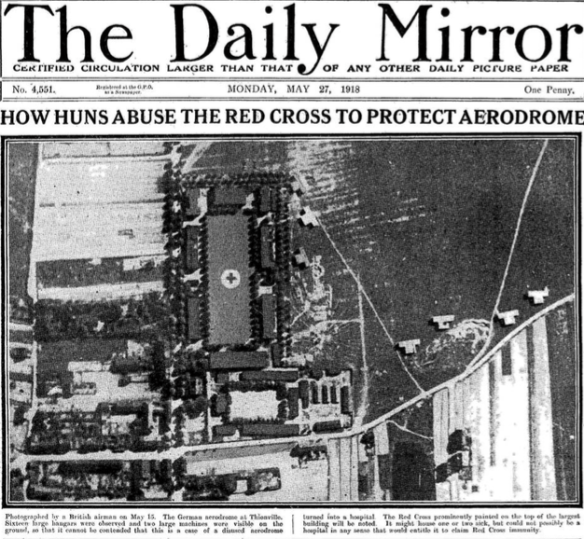

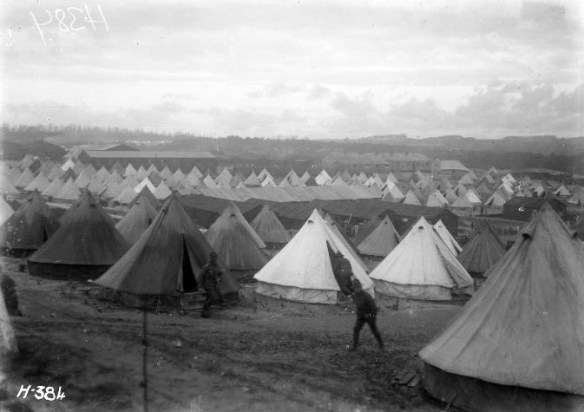

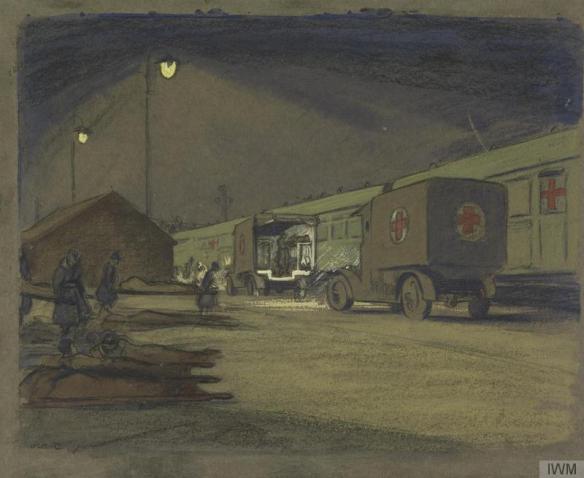

This is the fourth in a new series of posts on military violence against hospitals and medical personnel in conflict zones. It follows from my analysis of air strikes on base hospitals on the coast of France in 1918 here, and of the US air strike on the MSF Trauma Centre in Kunduz, Afghanistan in 2015 here and here. This post, together with the next in the series, is about Syria. They all derive from a new presentation – still in active development – called ‘The Death of the Clinic: surgical strikes and spaces of exception’ that will eventually become an essay in my next book, so I would appreciate any comments or suggestions.

The eye of the storm

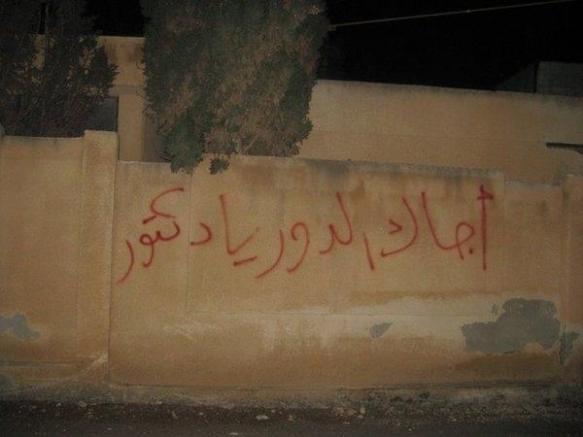

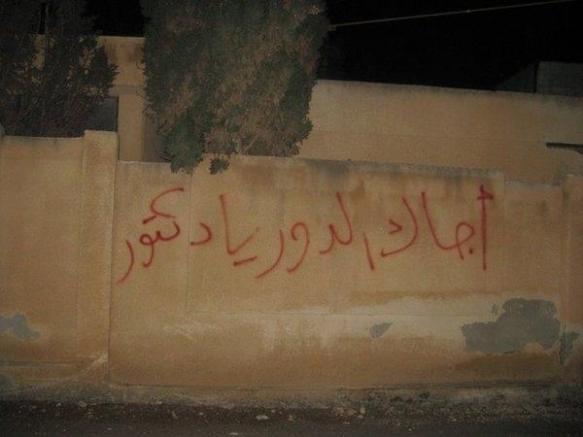

Syria’s civil war has multiple origins, but one of the most incendiary incidents took place on 16 February 2011 in the city of Dara’a 80 km south of Damascus near the Jordanian border. Inspired by the spread of the Arab uprisings east across the Maghreb from Tunisia, and the threat they posed to a succession of autocratic regimes, a group of local teenagers decided to daub slogans on the wall of their high school. One of them, a brave 15-year old (who now lives with his family in Jordan), painted this:

‘Ejak el door ya Doctor’ – ‘Your turn, doctor’.

The doctor in question was Bashar al-Assad, Syria’s president, who had trained as an opthalmologist in Damacus and London. In the months to come, Assad would give that slogan a viciously ironic twist.

The immediate response of the security forces to the graffiti was swift and draconian; the boys were rounded up, imprisoned and tortured (see here, here and here). When their relatives protested to the officer in charge he told them:

‘Forget your children. Just make more children. And if you don’t know how to make more, I’ll send someone to show you.’

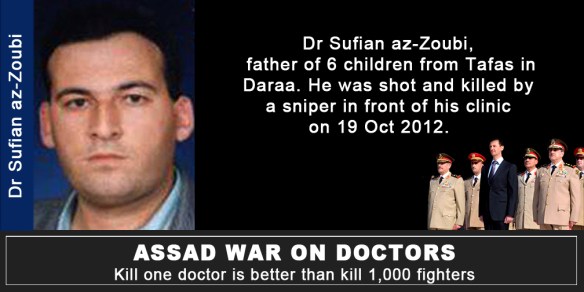

Local people took to the streets, and as the demonstrations spread on 22 March security forces entered the National Hospital in Dara’a, cleared it of all non-essential medical staff and stationed snipers on the roof who were under orders to fire on protesters. The hospital remained until military control until May 2013; admissions were restricted and snipers continued to fire on the sick and wounded who tried to approach the hospital. On 8 April security forces opened fire on thousands of demonstrators approaching a roadblock; ambulances were prevented from reaching the wounded, and a doctor, a nurse and an ambulance driver were killed when they tried to get through (UN Human Rights Council: ‘Assault on Medical Care in Syria’, 13 September 2013: download here; see also the Human Rights Watch report, ”We’ve never seen such horror’ here).

Local people took to the streets, and as the demonstrations spread on 22 March security forces entered the National Hospital in Dara’a, cleared it of all non-essential medical staff and stationed snipers on the roof who were under orders to fire on protesters. The hospital remained until military control until May 2013; admissions were restricted and snipers continued to fire on the sick and wounded who tried to approach the hospital. On 8 April security forces opened fire on thousands of demonstrators approaching a roadblock; ambulances were prevented from reaching the wounded, and a doctor, a nurse and an ambulance driver were killed when they tried to get through (UN Human Rights Council: ‘Assault on Medical Care in Syria’, 13 September 2013: download here; see also the Human Rights Watch report, ”We’ve never seen such horror’ here).

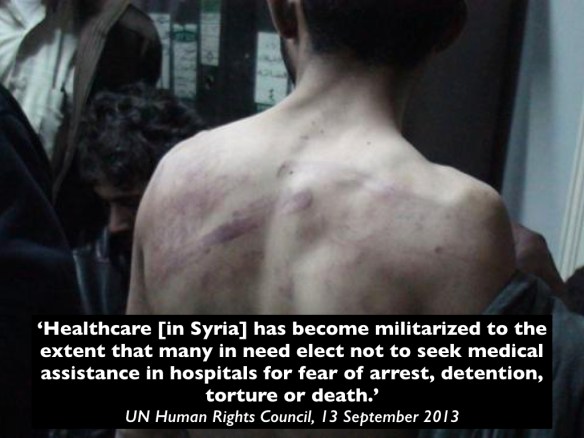

Others took up the cry, taking to the streets and chanting ‘Dara’a is Syria‘. In many other areas the government stationed snipers, armoured personnel carriers, tanks and heavy artillery at hospitals; doctors suspected of treating protesters were arrested and tortured; security forces forcibly removed patients from hospitals, ‘claiming bullet or shrapnel wounds as evidence of participation in opposition activities’; and ambulances transporting casualties were attacked and pharmacies looted.

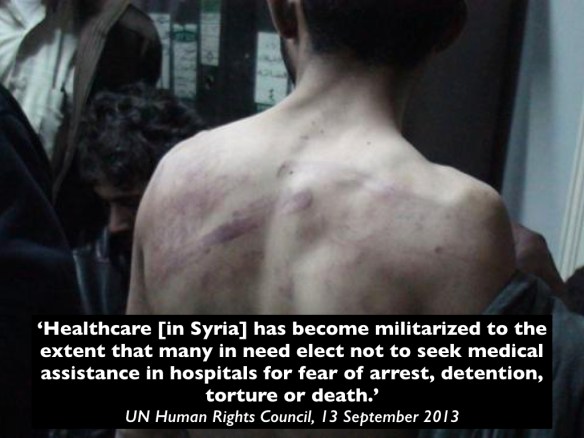

The UN Human Rights Council concluded:

This was, sadly, hardly novel. In 2006, at the height of sectarian violence in occupied Baghdad, for example, Muqtada al-Sadr‘s Shi’a militia controlled the Health Ministry and manipulated the delivery of healthcare in order to marginalise and even exclude the Sunni population. As Amit Paley reported:

‘In a city with few real refuges from sectarian violence – not government offices, not military bases, not even mosques – one place always emerged as a safe haven: hospitals…

‘In Baghdad these days, not even the hospitals are safe. In growing numbers, sick and wounded Sunnis have been abducted from public hospitals operated by Iraq’s Shiite-run Health Ministry and later killed, according to patients, families of victims, doctors and government officials.

‘As a result, more and more Iraqis are avoiding hospitals, making it even harder to preserve life in a city where death is seemingly everywhere. Gunshot victims are now being treated by nurses in makeshift emergency rooms set up in homes. Women giving birth are smuggled out of Baghdad and into clinics in safer provinces.’

He described hospitals as ‘Iraq’s new killing fields’, but in Syria the weaponisation of health care has been radicalised and explicitly authorized by the state.

Counterterrorism and the criminalisation of health care

Doctors were systematically targeted for treating anyone who opposed the government. In April 2012 one surgeon from Idlib told Annie Sparrow:

‘We were detained in the hospital for several days. Tanks parked out front, artillery in the wards, snipers on the roofs shooting patients who tried to come. They took our names, and summoned three of the five security branches – state, political and military. I was interrogated and forced to sign several commitments not to treat anyone not pro-regime. Of course, as soon as I was released I violated it immediately…the city was full of wounded and sick people. Soon after that a friend who worked in military security let me know I was now “wanted” [for my work], the charge being that I was the leader of a terrorist group. So I went into hiding, and moved my family to Turkey. In retaliation my brother was executed.’

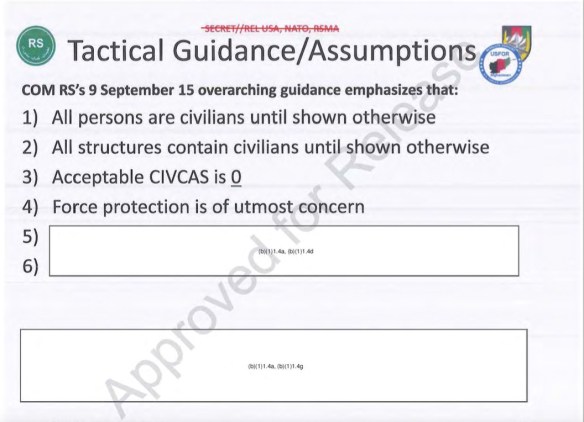

The State of Emergency that had been in force in Syria since 1962 was abruptly ended on 21 April 2012. But on 2 July a new Counter-terrorism Law came into force that criminalised all medical aid to the opposition. Here is Annie Sparrow again:

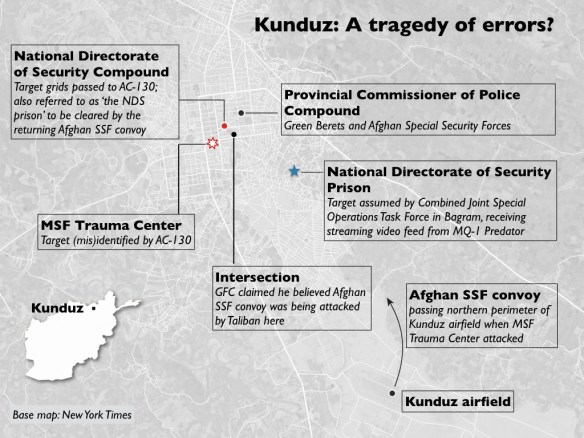

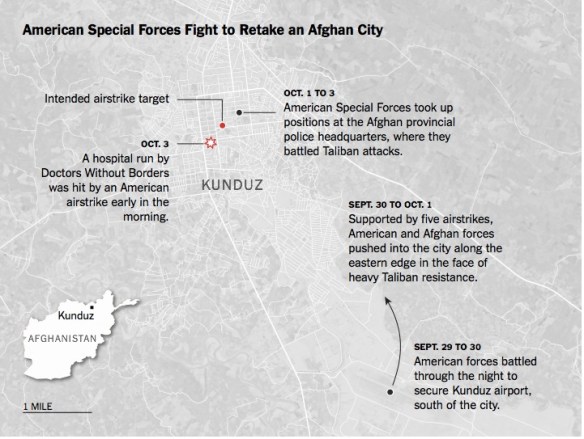

The parallels with the objections voiced by some members of Afghanistan’s security services against MSF’s work in Kunduz are only too clear: but in Syria they have been given explicit state sanction enforced through the law.

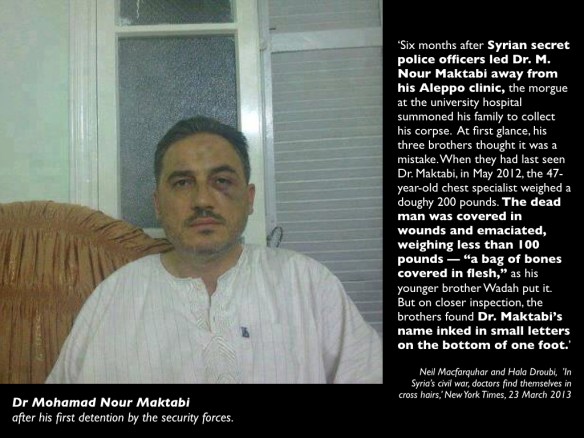

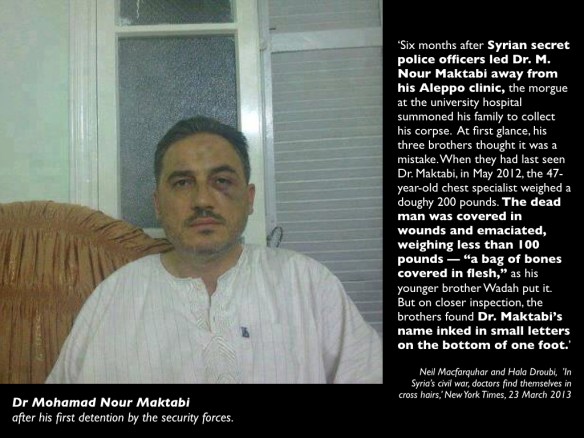

As Neil Macfarquhar and Hala Droubi reported for the New York Times in March 2013, doctors repeatedly found themselves in the cross-hairs. Here, for example, is the case of Dr Mohamad Nour Maktabi:

The Counter-terrorism Law also declared that all medical facilities operating in opposition-held areas without government permission were illegal – and thereby transformed them (under Syrian law, at least) into legitimate targets of military violence.

Air wars and ‘surgical strikes’

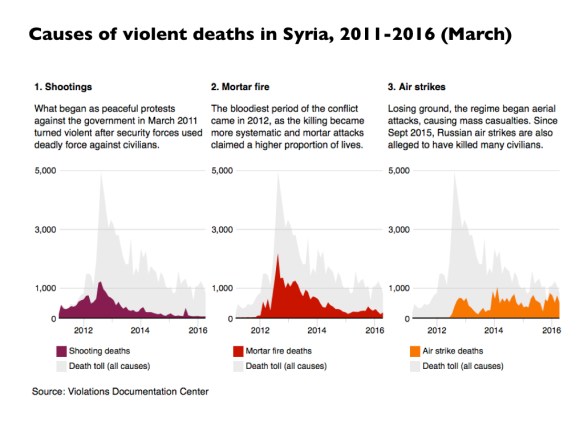

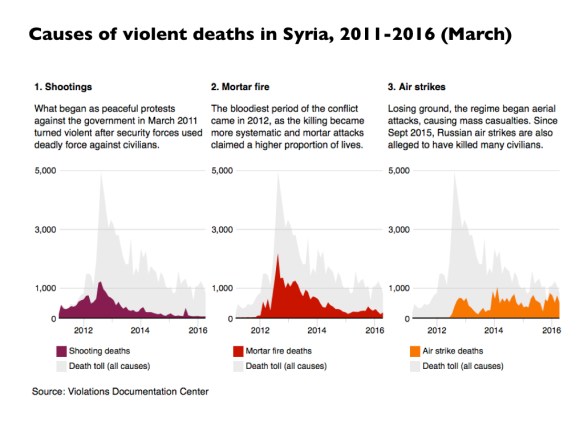

The nature of military and paramilitary violence has changed during the course of the war; shooting and mortar-fire have increasingly been supplemented by air strikes.

Even in the early stages of the war doctors were confronting what one trauma specialist called ‘unimaginable injuries’. Dr Rami Kalazi, a neurosurgeon in east Aleppo, explained:

‘In the beginning, we saw new injuries that we did not know how to treat. Fortunately, at the beginning of the revolution and when we began working in field hospitals, there was more freedom of movement. In 2012 and 2013, there was no such thing as “barrel bombs” and there was no violent shelling from airplanes, so many visiting foreign doctors came…

‘But even so, they told us that they were seeing injuries that they had never seen before in books or textbooks or in the hospitals where they worked in their home countries. Unfortunately, reality forces you to learn.’

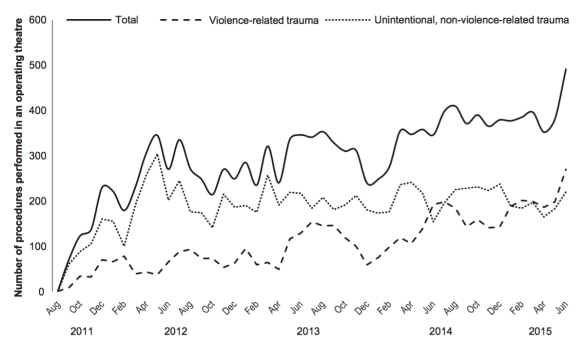

But air strikes transformed the calculus of injury. Many more casualties resulted from each attack, and the wounds of those who survived were often far more serious.

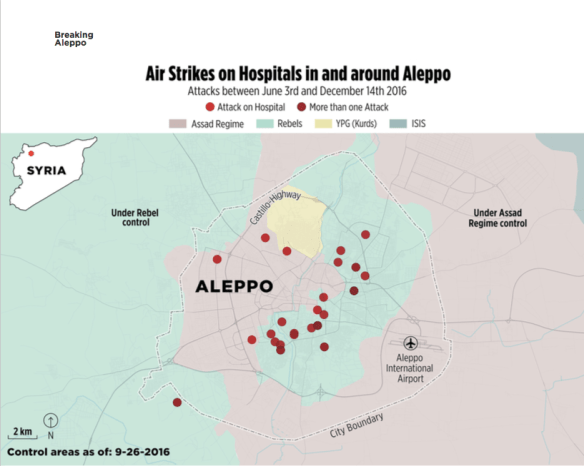

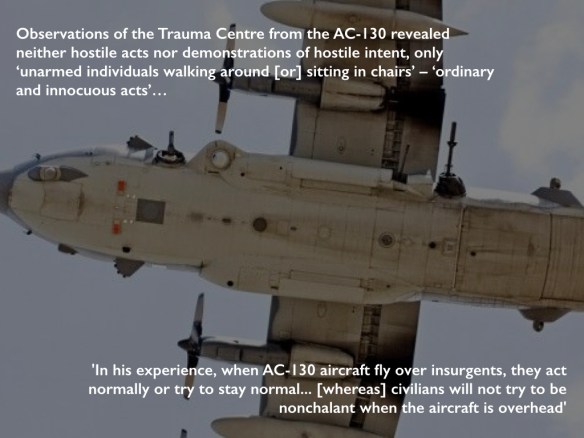

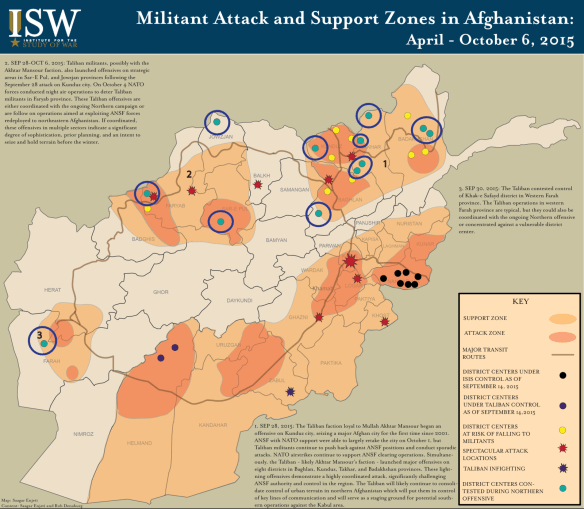

The US-led coalition has carried out multiple airstrikes primarily in areas controlled by IS, and the campaign has caused (minimally) hundreds and probably several thousand civilian casualties – see my analysis of specific US air strikes here and here, for example – but the Syrian Arab Air Force has concentrated its fire on areas controlled by other rebel groups (see Jeffrey White‘s analysis here).

A favourite tactic has been the deployment of ‘barrel bombs‘ – in effect, aerial IEDs: oil drums filled with high explosive and cut rebar to act as shrapnel – dropped from helicopters (see Human Rights Watch here). Basel al-Junaidi described witnessing their impact:

I saw the aftermath of a barrel bomb. I saw human remains scattered in the street; I heard the screaming. I’m trained as a doctor, but I was unable to act. I just stood there, petrified. The West thinks we’re used to this, but we aren’t of course. We’re like anyone else – we use computers and cars, not camels and tents…

Another doctor who worked in Syria said he kept ‘a drawing from a second grader in Aleppo, showing helicopters bombing the city, blood and destruction below.’ Chillingly, ‘the dead children are smiling while the living ones are crying.’

From September 2015) the Russian Air Force, often acting in concert with the Syrian Arab Air Force, has also concentrated on targets in areas controlled by other opposition groups:

Russia has routinely denied these charges, but from 30 September to 12 October 2015 its Ministry of Defence published videos of 43 airstrikes. Bellingcat, aided by crowdsourcing, identified the exact location of 36 of them and overlaid them on the ministry’s own map identifying which groups controlled what parts of the country (see the full report, ‘Distract, Deceive, Destroy’, here):

‘The result revealed inaccuracy on a grand scale: Russian officials described 30 of these videos as airstrikes on Isis positions but in only one example was the area struck in fact under the control of Isis, even according to the Russian MoD’s own map.’

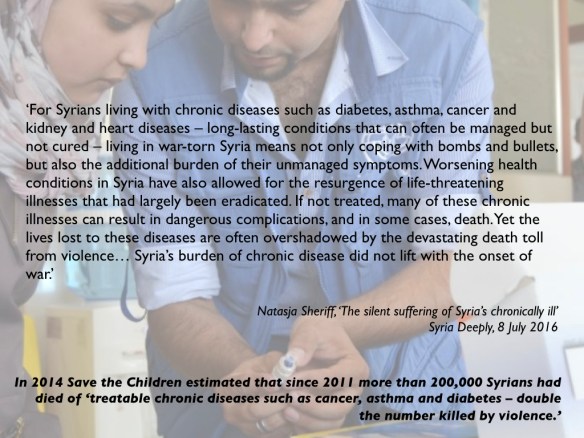

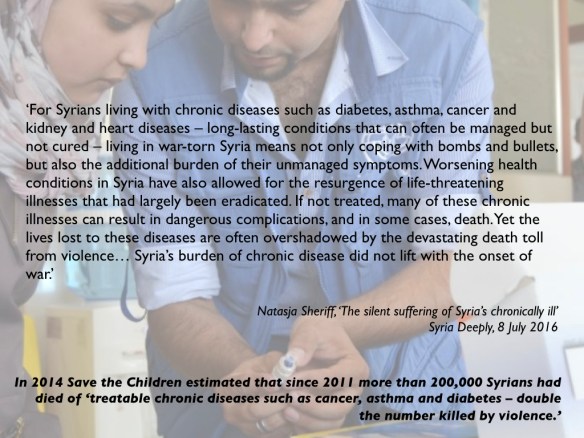

The effect of these air strikes has been devastating on the population at large. To make matters even worse, air strikes cannot target individual doctors and have instead frequently been directed against hospitals and other medical facilities. This compromises not only trauma care for the wounded but also the treatment of chronic and infectious diseases:

(You can find a discussion of the problem of infectious diseases in Sima L. Sharara and Souha S. Kanj, ‘War and infectious diseases: challenges of the Syrian Civil War’, PLOS Pathogens 10 (11) (2014) here).

Hospitals and bomb sights

Doctors and other medical staff had to adjust to a new, sickening vulnerability. Here is one OB/GYN who was still working in a hospital in East Aleppo when she was interviewed on Public Radio International in August 2016:

Carol Hills, PRI: Doctor Farida, did I just hear a noise there? Was that some sort of attack that I just heard?

Dr Farida Almouslem: It’s attack. [Laughs]. It’s normal. It’s away from me. Not next to me. These noises are all the time.

Hills: Do you and the doctors and patients you work with feel safe inside the place where you’re working?

Dr Farida: No. It’s not safe. I work at the third floor in my hospital. And many times the wall was perforated. So every woman came to the hospital, she knows that there is a danger on her life. So they just give the delivery, or give the birth, and then go home. She escapes to home because she knows our hospital is always targeted.

Other doctors in opposition-held areas said the same. Here is Dr Mohamed Tennari, director of an above-the-ground field hospital in Idlib:

‘When I am in the hospital, I feel like I am sitting on a bomb. It is only a matter of time until it explodes. It is wrong − a hospital should not be the most dangerous place. I wish I could say that targeting a hospital in Syria is unique, but is not.’

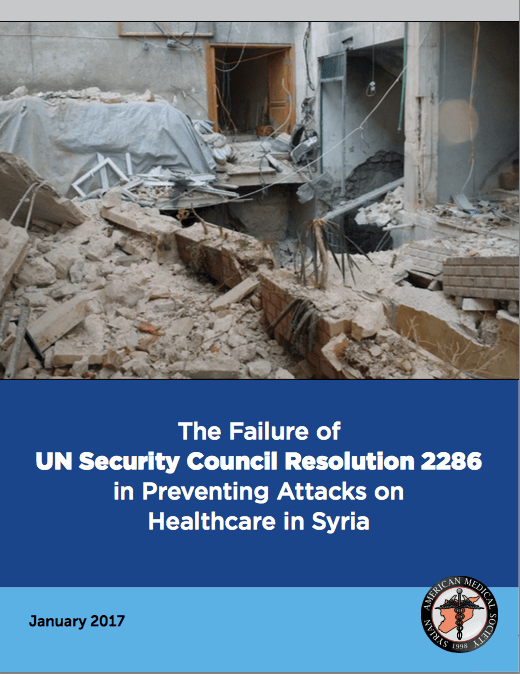

In fact, it’s far from unique: Physicians for Human Rights has issued a report detailing Attacks on Doctors, Patients and Hospitals hospitals and provided a interactive map of attacks on healthcare in Syria.

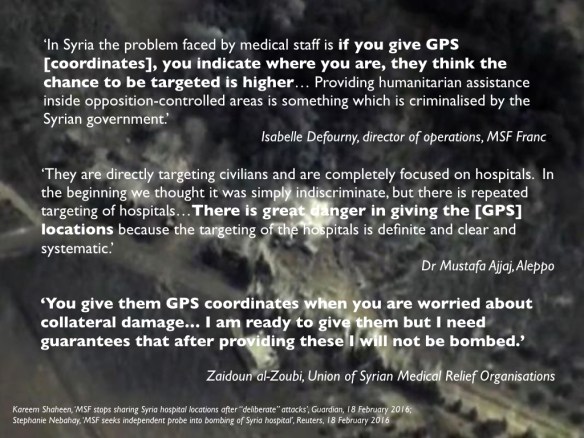

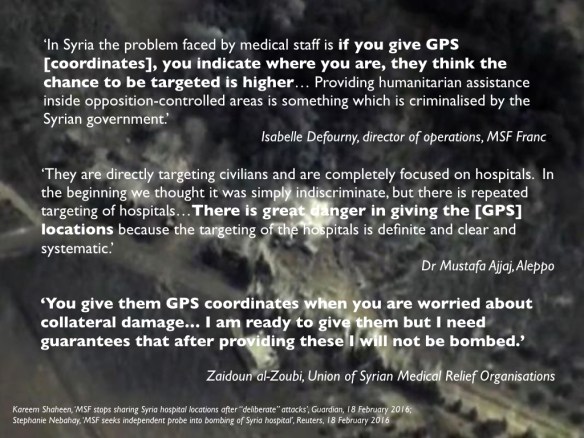

In the face of these escalating attacks, hospitals in opposition-held areas have tried to conceal their locations from the Syrian government. In contrast to the protocol adopted by the MSF Trauma Centre in Kunduz, they have been markedly reluctant to provide their GPS coordinates (and see MSF’s explicit comparison between what happened in Kunduz and the situation in Syria here):

But this has trapped them in a grim Catch-22. Michiel Hofman of Médecins sans Frontières – which is not permitted to operate in government-controlled areas in Syria – explains:

‘Hospitals that MSF supports in Syria are bereft of the possible protection of being clearly marked as a hospital or sharing of GPS coordinates, as the Syrian government passed an anti-terrorist law in 2012 that made illegal the provision of humanitarian assistance – including medical care – to the opposition, forcing most health structures to go underground and operate without governmental medical registration. The bombing parties can then conveniently claim they were unaware it was a hospital they hit.’

More often, the Syrian government and its allies routinely describe the bombed building as a ‘so-called hospital’. After an air strike on an MSF-supported hospital near Maarat al-Numan in Idlib on 15 February 2016 Bashar Jaafari, Syria’s ambassador to the United Nations, made this statement:

‘The so-called hospital was installed without any prior consultation with the Syrian government by the so-called French network called MSF which is a branch of the French intelligence operating in Syria… They assume the full consequences of the act because they did not consult with the Syrian government. They did not operate with the Syrian government permission.’

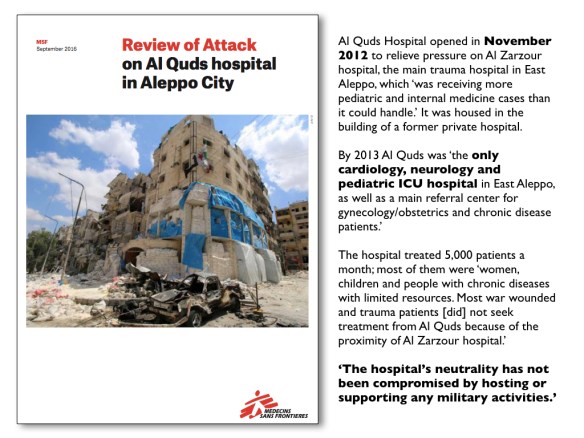

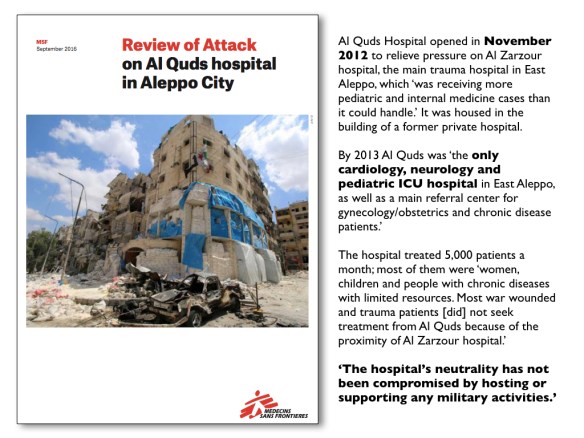

The allies of the Syria government are not confined to Russia and Iran. On 27 April 2016 the Al Quds hospital in Aleppo was hit by two air strikes that killed 55 people – among them two specialists, including Dr Muhammad Waseem Maaz, Al Quds’s pediatrician – and severely damaged the hospital. When it partially reopened 20 days later its capacity was reduced from 34 to 12 beds. MSF conducted a detailed review of the operations of the hospital and the circumstances of the attack:

Here is Professor Tim Anderson on what he calls ‘The “Aleppo Hospital” Smokescreen‘ (and for reasons that will become obvious I am so tempted to put scare-quotes around the title that adorns his post; the Department of Political Economy at the University of Sydney lists him as a Senior Lecturer not a Professor, but perhaps anxiety over the appellation ‘Doctor’ is contagious):

‘…the story of Russian or Syrian air attacks on the ‘al Quds hospital’ gained prominence in the western media… CCTV showed people leaving this ‘hospital’ before an explosion.

‘The building is in the southern al-Sukkari district, which has been a stronghold of Jabhat al Nusra for some years. Many Aleppans had never heard of ‘al Quds hospital’. Dr Antaki [Aleppo Medical Association in Western Aleppo] says: “This hospital did not exist before the war. It must have been installed in a building after the war began”…. This facility was not a state-run or registered facility.’

Anderson is joined in his disinformation effort by Eva Bartlett writing in the ‘OffGuardian’:

‘Dr. Zahar Buttal, Chairman of the Aleppo Medical Association … said: “The media says the only pediatrician in Aleppo was killed in a hospital called Quds. In reality, it was a field hospital, not registered.”

As for the pediatrician, “We checked the name of the doctor and didn’t find him registered in Aleppo Medical Association records.”…

… central to the lies were the bias and propaganda of the very partial, corporate-financed Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), which supports areas in Syria controlled by terrorists, specifically Jabhat al-Nusra…’

To repeat: the Syrian government has refused to register or recognise any hospitals operating in areas outside its control – hence the snide reference to ‘so-called hospitals’ and Anderson’s meretricious scare-quotes – and it does not permit MSF to operate in areas under its control (despite repeated requests). As for the disappearance of Dr Muhammad Waseem Maaz from the Syrian government’s registry (though I have no doubt he was on other lists maintained by the regime) the director of the Children’s Hospital in Aleppo provides a graceful tribute to him here. And here is the doctor whose death these commentators dismiss so lightly (if you have the stomach for it, you can see his last moments caught on CCTV here):

What, apart from the grotesque stipulations of the Syrian state, makes them think it proper to withdraw medical care from those living – surviving – in rebel-held areas? International humanitarian law is unequivocal: they are entitled to medical treatment and to be protected whilst it is provided to them.

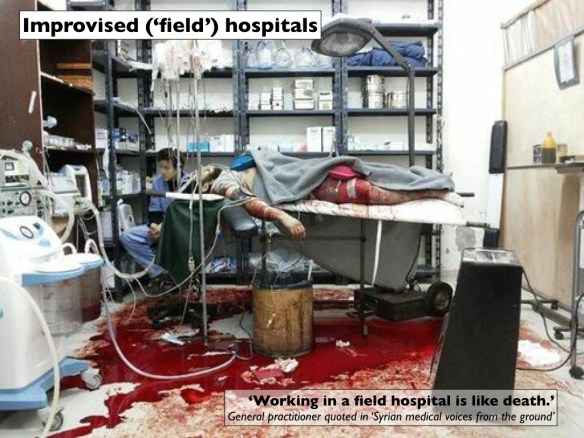

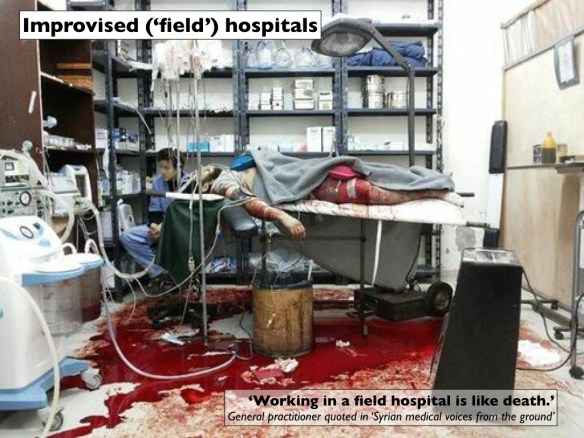

In rebel-held areas medical care has increasingly moved outside what were once established hospitals into the clandestine ‘field hospitals’ referred to above, which have been given numbered code-names to conceal their locations. Some, like those established by MSF, follow strict medical protocols and, according to a study of one operating in Jabal al-Akrad by Miguel Trelles and his colleagues, they have (for a time) been able to provide high-quality medical care with remarkable survival rates (‘Providing surgery in a war-torn context: the Médecins Sans Frontières experience in Syria’, Conflict and Health (December 2015)). As the attacks on them have increased and qualified personnel and medical supplies have become scarce, however, many have become exercises in improvisation:

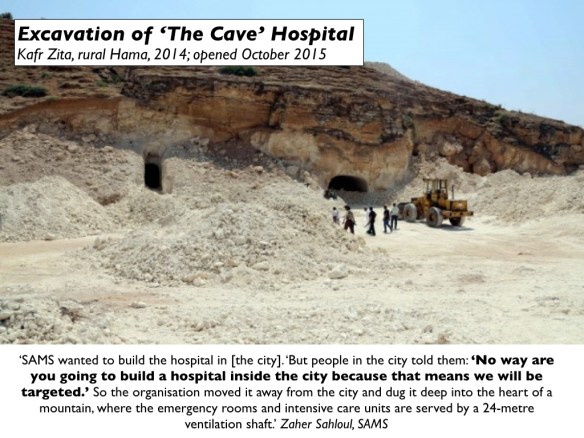

Some of these hospitals have literally gone underground. ‘‘In our worst dreams – in our worst nightmares – we never thought we would have to fortify hospitals,’ declared Dr Zaidoun al-Zoabi of the Union of Medical Care and Relief Organizations. ‘It’s not humane. It’s impossible to comprehend.’

Subterranean locations have been used not only to protect the hospitals but also to protect local populations. Charles Davis reported that

‘whether it’s a vehicle or a building, anything that’s identifiable as providing medical care is ripe for an airstrike, so that staff have now taken to covering up any distinguishing characteristics. Even so, [Dr Abdulaziz Adel, a surgeon in East Aleppo, admits that] local residents are “always begging us to go away, take your hospital away from us or otherwise we’ll be a target.”‘

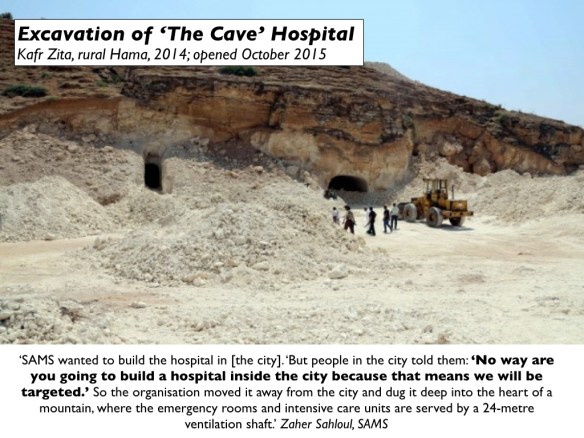

When the Syrian-American Medical Society proposed to build a hospital in Hama in 2014, local people begged them to locate it outside the city and so SAMS excavated what became the Dr Hasan al Araj Hospital, better known as ‘The Cave’:

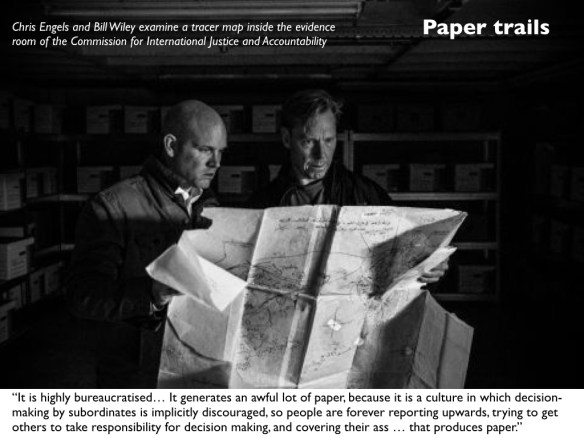

Supply chains and kill-chains

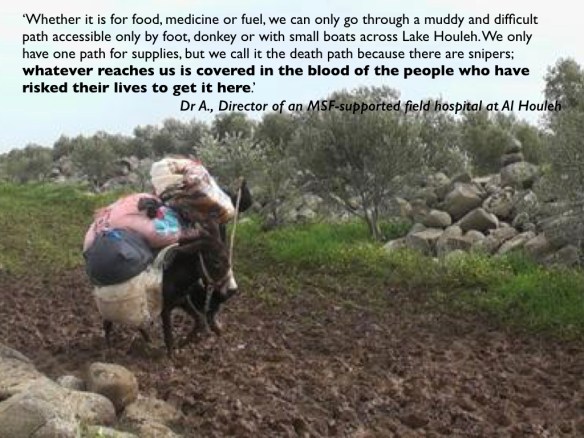

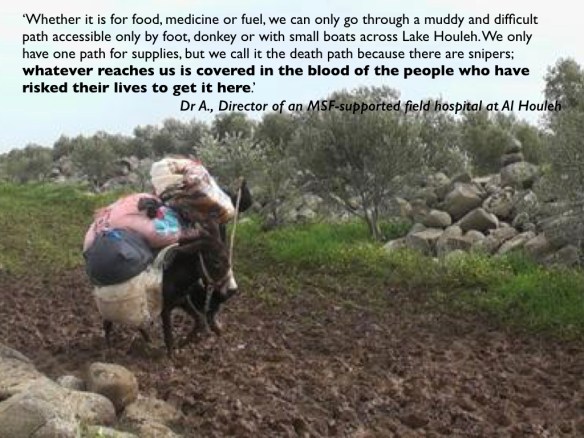

As the civil war ground on, even the most basic medical supplies became scarce and obtaining them ever more dangerous. In March 2015 MSF reported that:

‘Even if it is available, many suppliers do not want to risk selling material like gauze or surgical threads when they know it is going to be sent into North Homs. Gauze is considered synonymous with war surgery, and often a supplier is not willing to take the risk of being arrested or shut down for supplying a besieged area.’

You can read more here and here. One doctor told MSF:

‘It is precious, dangerous, incriminating. There are secret outlets supplying us with gauze.’

At the end of last year the Guardian provided this image of one of the secret factories:

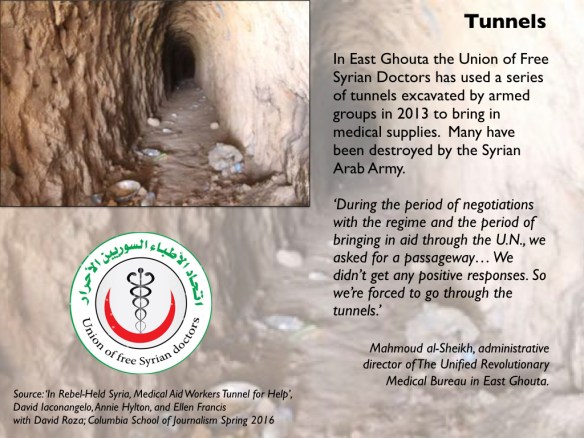

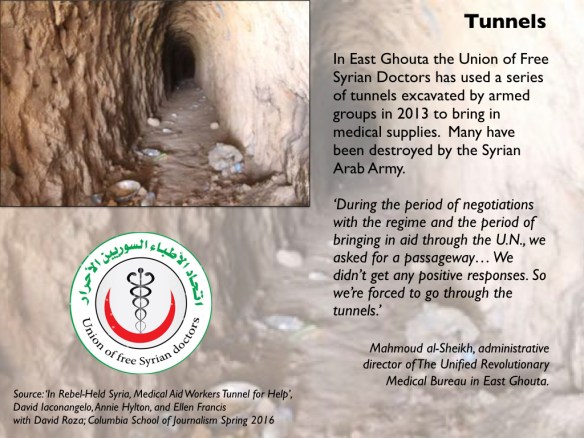

In East Ghouta, hospitals have been forced to use tunnels to bring in medical supplies (more from Ellen Francis and her colleagues here):

The risks are formidable and the costs have been almost prohibitive. Ellen Francis and her colleagues at Columbia’s Graduate School of Journalism report that in January 2014 the Free Syrian Army and the Syrian Arab Army agreed an uneasy and ragged cease-fire in Barzeh, a small town on the northern edge of Damascus. There a team from the Union of Free Syrian Doctors was able to buy medical supplies from merchants who travelled out from the capital.

The merchants paid a 20 per cent ‘customs fee’ to Syrian Army soldiers; the agents for the doctors then paid a ‘tax’ to get the supplies through the Harasta checkpoint on the Army-controlled highway, and then a ‘toll’ to the rebels (‘tunnel lords’) who controlled the tunnels into Ghouta.

The combined fees inflated the price of medical supplies. A litre of serum used to help the body replenish lost blood cost $1 in government-controlled areas and $3.50 to $10 via the tunnel route. Ghouta was using about 10,000 litres of serum per month. The supply chain was subsequently severed once Barzeh itself came under siege and was cut off from Damascus.

Some humanitarian aid has crossed the lines by more conventional routes – conventional for a war zone at any rate – but medical supplies have routinely been removed from aid convoys. On 19 May 2016 the UN Secretary-General reported to the Security Council:

‘[By May] 2016, WHO [had] submitted 21 individual requests to the Government of the Syrian Arab Republic to deliver medical supplies to 82 locations in 10 governorates. The Government approved five requests [while] 16 requests remained unanswered.

‘The removal of life-saving medicines and medical supplies continued, with nearly 47,459 treatments removed from convoys in April intended for locations in Homs, Aleppo and Rif Dimashq governorates. Removed items included surgical supplies, emergency kits, trauma kits, mental health medicines, burn kits and multivitamins. Removals extended to basic items, such as antibacterial soap, which was removed from midwifery kits. Items were also removed from other kits, notably surgical tools…’

Even then, aid convoys are not safe. Four months later to the day a UNICEF aid convoy delivering supplies to a Syrian Red Crescent warehouse at Urum al-Kubra in Aleppo was attacked from the air, killing at least 18 people and destroying 18 of the 31 trucks. Most analysts have concluded that the Russian Air Force was responsible, perhaps acting in concert with the Syrian Arab Air Force – see for example here and here– but the Russian Ministry of Defence and the usual suspects have variously blamed spontaneous combustion, a ground attack by rebels and a US drone attack.

These shortages are threaded into dispersed and precarious siege economies that gravely affect the health of local populations. In December 2015 an estimated 400,000 people were surviving without access to life-saving aid in 15 besieged locations across Syria; the figures gathered by Siege Watch are even higher.

Surrounded by 6,000 land-mines and 65 sniper-controlled checkpoints, Madaya’s 40,000 inhabitants have been under siege since July 2015; 32 people died of starvation and malnutrition in December 2015 alone. One resident interviewed by Amnesty International in January 2016 described the catastrophic situation:

‘Every day I wake up and start searching for food. I lost a lot of weight, I look like a skeleton covered only in skin. Every day, I feel that I will faint and not wake up again… I have a wife and three children. We eat once every two days to make sure that whatever we buy doesn’t run out. On other days, we have water and salt and sometimes the leaves from trees. Sometimes organizations distribute food they have bought from suppliers, but they cannot cover the needs of all the people.

‘In Madaya, you see walking skeletons. The children are always crying. We have many people with chronic diseases. Some told me that they go every day to the checkpoints, asking to leave, but the government won’t allow them out. We have only one field hospital, just one room, but they don’t have any medical equipment or supplies.’

An aid convoy was allowed in four days after this interview.

There are also grave shortages of skilled medical personnel. The doctors who remain in opposition-held areas have all had to learn new skills sometimes far beyond their original training. In March 2015 one young surgeon working in an MSF-supported hospital east of Damascus recalled:

‘There was a pregnant woman who was trapped during the time we were under full siege. She was due to deliver soon. All negotiation attempts to get her out failed. She needed a cesarean operation, but there was no maternity hospital we could get her to, and I had never done this operation before.

A few days before the expected delivery date, I was trying to get a working internet connection to read up information on doing a C-section. The clock was ticking and my fear and stress started to peak. I wished I could stop time, but the woman’s labour started…’

In 2015 OCHA estimated that more than 40 per cent of pregnant women in these areas now scheduled C-sections to reduce the risk of an attack preventing them from obtaining care.

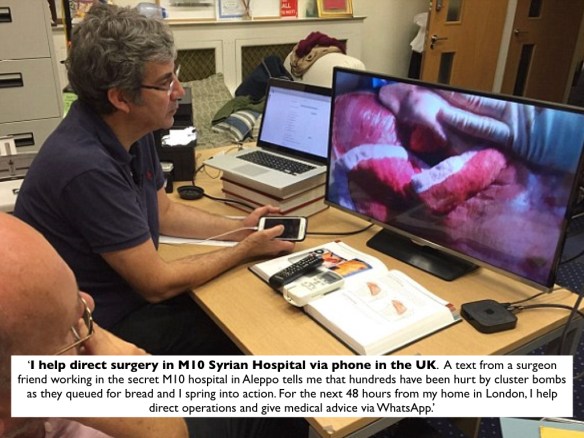

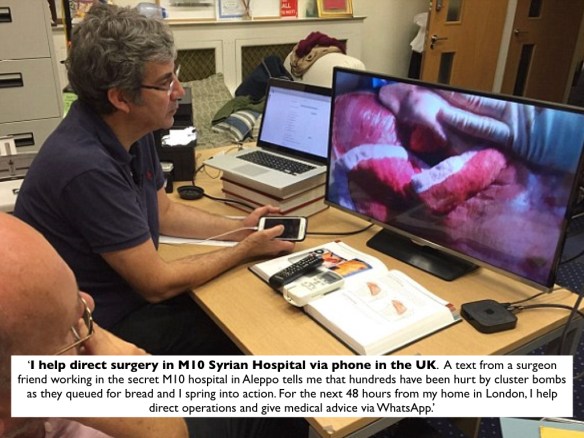

In some cases doctors can call on skilled overseas help via Skype from consultants on call 24/7 in the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom. Ben Taub has written movingly of the extraordinary efforts of what he calls ‘the shadow doctors’ enlisted in ‘the underground race to spread medical knowledge as the Syrian regime erases it.’ One of the most active is Britain’s Dr David Nott:

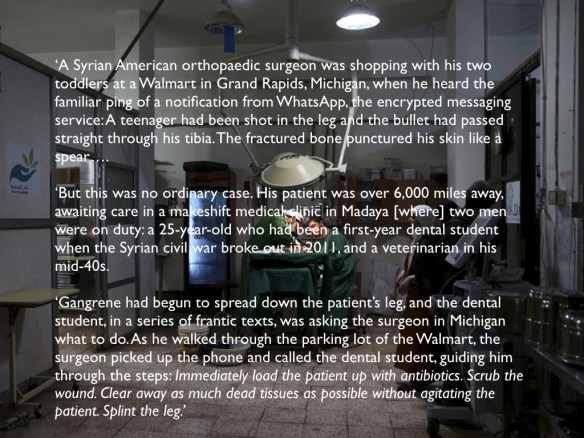

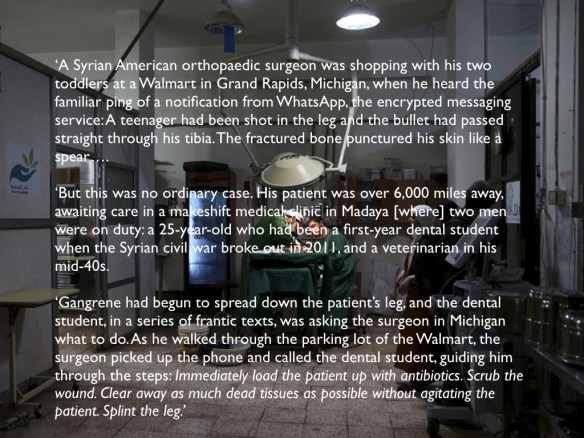

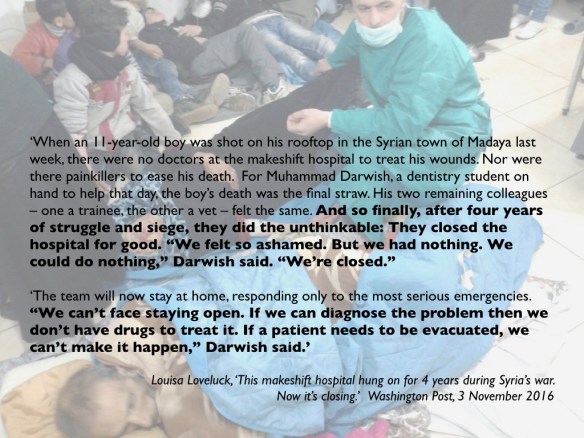

But not all those seeking specialist help are qualified surgeons. In the field hospital serving the besieged town of Madaya medical care has been provided by a dentist, a dental student and a veterinarian. Avi Asher-Schapiro reports:

‘The five-year civil war has plunged the Madaya clinicians into the deep end, forcing them to perform medical procedures that push them far beyond their training. They have treated countless gunshot victims, performed seven amputations, over a dozen C-sections, and diagnosed everything from meningitis to cancer.’

As he explains, this remarkable trio has also relied on remote medicine:

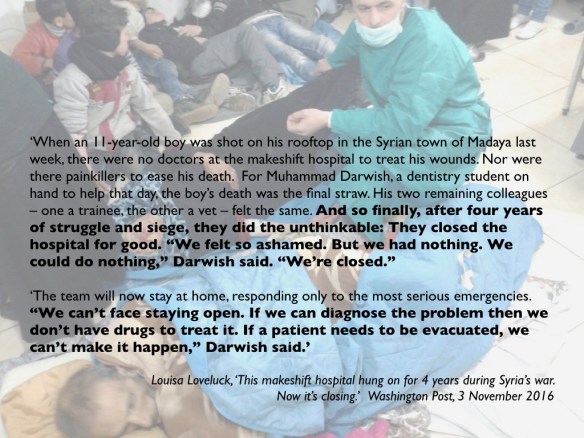

These are all extraordinary responses to near-impossible, life-threatening situations. But their successes have been short-lived.

The Madaya clinic was forced to close in November 2016:

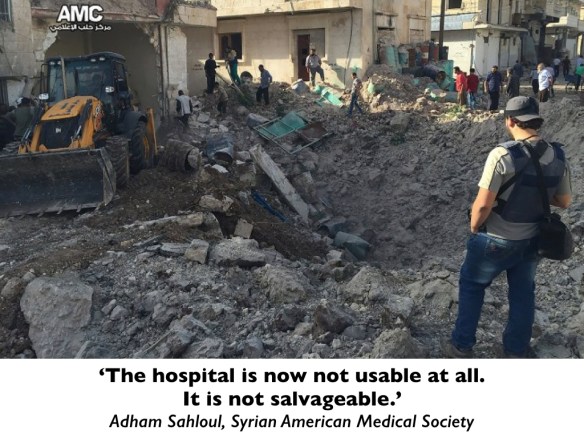

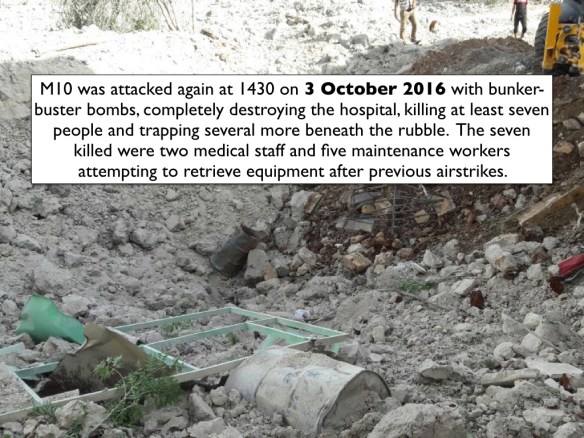

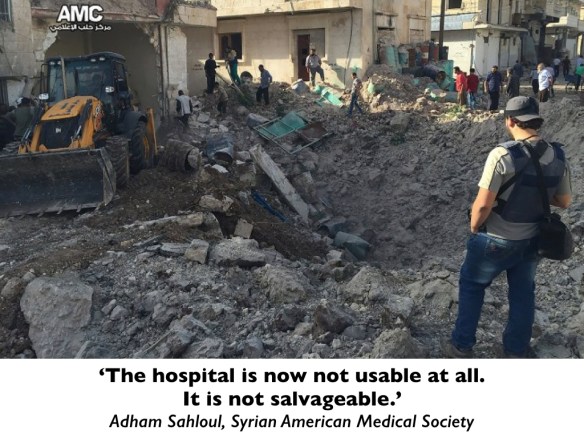

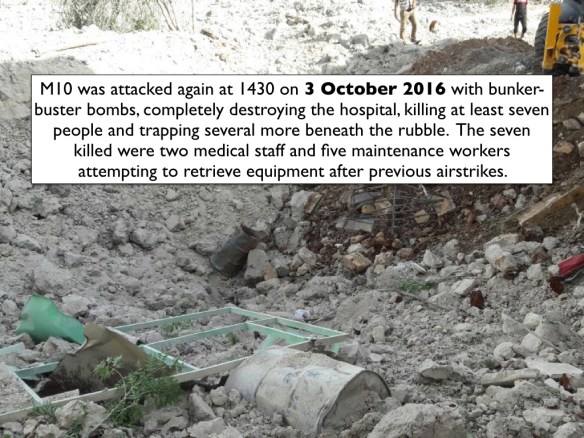

And the M10 hospital where Nott helped direct surgery – the largest trauma and ICU centre in East Aleppo – was hit by successive, catastrophic air strikes. First, an attack on 28 September 2016 left only half the hospital operational. On 1 October Xisco Villalonga, MSF’s Director of Operations, reported that

‘Bombs are raining from Syria-led coalition planes and the whole of east Aleppo has become a giant kill box.’

That night multiple strikes on M10 killed two people and injured ten others; the hospital had to be evacuated because one crater was so deep there were fears that the rest of the building would collapse.

But the ordeal was not over: there were further, devastating strikes on 3 October:

The underground hospitals have fared no better. ‘The Cave’ – 15 metres inside a mountain, remember – was hit by two ‘bunker-buster’ bombs at 1500 on 2 October 2016. After 35 staff and patients had been evacuated a second strike occurred in the early evening involving missiles and cluster bombs. The E.R. was wrecked, ceilings collapsed, cement walls crumbled and generators, water tanks and medical equipment were destroyed (see image below). Nobody was seriously injured but the hospital sustained critical damage and has been closed indefinitely. It used to treat 300 patients and perform 150 surgeries a month.

The exception to the exception

Once safe places under the protection of international humanitarian law – the exception to the space of exception that is the conflict zone – hospitals have become the targets of a new and extraordinarily vicious modality of modern war. The systematic attacks on hospitals have not only threatened the lives of patients and healthcare workers; they have also made many patients reluctant to seek medical treatment at all. In February 2015 a report from the Centre for Public Health and Human Rights at Johns Hopkins University was already warning of the consequences:

‘Unless they feel their life is in danger, many people won’t go to hospital because it is targeted for bombardment’ [Physician, Aleppo]. Two physicians reported that fear of travel and an understanding that the hospital is a target has led to a 50% decrease in clinic visits and surgery cases, even though the level of violence has not decreased.

Dr Farida, the OB/GYN in East Aleppo interviewed earlier, no longer has a hospital to work in – the last remaining hospital was reduced to rubble and closed on 18 November – and she now provides what medical care she can from a basement:

‘People know it’s a basement, but they are afraid to come here because they know any health facility is deliberately targeted by the regime. For women, they are afraid to come — but they don’t have any other option. When they don’t have a car or fuel to come here, they have to give birth at home. Women are bleeding at home and babies are born dehydrated without oxygen.’

Those that do make the precarious journey to a field hospital or other medical facility almost always now find that their care is compromised by the shortage or even the absence of doctors, nurses, medical supplies and even the most basic medical equipment. So doctors use ordinary sewing cotton instead of surgical thread; local anaesthetic where they would normally use a general, or even home-made, improvised variants. Dr Zaher Sahloul, who still tries to provide help to colleagues in Syria from his home in Chicago via WhatsApp, explains:

‘We operate on the mindset that they have basic things we take for granted… The reality is, they don’t have 90 percent of the things we think they have. They know better what they have and what they can do with it. These people are facing decisions we will never face in our lives. If you have 10 patients dying, who will you see first? Do you use spoiled gauze and dirty tubes at the risk of infection? It’s Hell for them.’

As I write, the Syrian Arab Army and its supporting militias are advancing into East Aleppo, where air strikes and artillery bombardments have left more than 250,000 people without access to any form of advanced medical care. The World Health Organisation announced that ‘although some health services are still available through small clinics, residents no longer have access to trauma care, major surgeries, and other consultations for serious health conditions.’

The final irony – although in this catalogue of horrors it probably isn’t the last at all – is that the Kremlin has announced that it will send two mobile hospitals to treat patients from East Aleppo. The Defence Ministry will operate ‘a special 100-bed clinic with trauma equipment for treating children’ and the Emergencies Ministry will provide a 50-bed clinic capable of treating 200 outpatients a day.

While the Kremlin congratulates itself on its ‘humanity’, we need to remember that this minimalist contribution would not have been necessary at all had medical neutrality been respected and doctors and nurses, hospitals and clinics not been so ruthlessly, systematically and deliberately targeted in the first place.

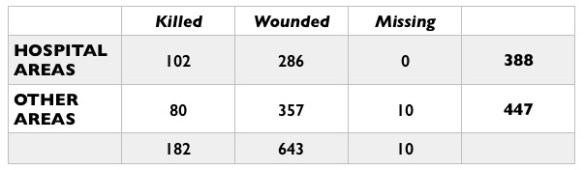

UPDATE: On 5 December the Defence Ministry’s mobile hospital (set up in West Aleppo to treat patients from East Aleppo) came under mortar fire from the crumbling opposition-held area to the east; one Russian doctor and two paramedics were killed. It’s not clear whether the hospital was deliberately targeted – there have been accusations that the co-ordinates of the hospital must have been given to the militants for it to have been hit ‘right at the moment when it started working‘ – or whether it was caught in the indiscriminate shelling and mortar-fire that has hit other hospitals in West Aleppo.

But I should make two things clear. First, attacks on hospitals in West Aleppo – even though I don’t think they have exhibited anything like the scale or the systematicity of those directed against medical facilities and healthcare workers in opposition-held areas – are as reprehensible as those on hospitals in the East. Second, the muted response from the US-led coalition to the shelling of the Russian field hospital is deeply disturbing. The International Committee of the Red Cross announced after the attack that ‘all sides to the conflict in Syria are failing in their duties to respect and protect healthcare workers, patients, and hospitals, and to distinguish between them and military objectives.’ The Russian Ministry of Defence dismissed this as a ‘cynical’ display of indifference to the deaths of its doctors, but I don’t read it like that at all – what is cynical is the partisan appeal to medical neutrality when it suits, and its systematic violation when it doesn’t.

To be continued

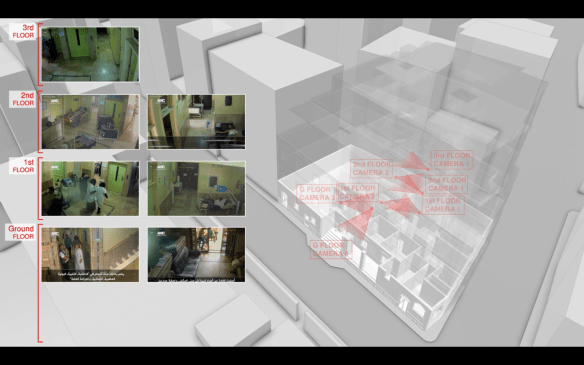

The Atlantic Council has issued a new report, Breaking Aleppo, which uses satellite imagery, CCTV clips, social media and video from the Russian Ministry of Defence and the RT network to explore the siege of eastern Aleppo and in particular attacks on civilian targets and infrastructure.

The Atlantic Council has issued a new report, Breaking Aleppo, which uses satellite imagery, CCTV clips, social media and video from the Russian Ministry of Defence and the RT network to explore the siege of eastern Aleppo and in particular attacks on civilian targets and infrastructure.