Forthcoming from Hurst in the UK – who have an expanding catalogue of books on the Middle East that is full of delights – and Columbia University Press in North America (September/October 2012), this edited collection on Orientalism and War emerged from a superb conference I attended at Oxford in June 2010.

But it’s not the usual quick-and-dirty “Proceedings” volume; Tarak Barkawi and Keith Stanski have done a marvellous job of editing, and the papers have all been revised for publication. I’ve listed the Contents at the end of this post.

In their Introduction, Tarak and Keith treat Orientalism as a regime of truth:

‘For us, this focus on Orientalism as an institutionalized community of experts is crucial. Orientalism is not mere bias against Easterners; it is a regime of truth. Views that in fact amount to grotesque misrepresentation come to be accepted by the authorized experts and by those they communicate with. One such misrepresentation that sits at the core of historical and contemporary Orientalisms concerns the East as a site of disorder and the West as that which brings order to disorder.’

The gavotte between order and disorder is one of the central ways in which Orientalism is so deeply entangled with war, and – as they also note – ‘war entails a cycle of the unmaking and remaking of truths of all kinds.’ In particular, war has ‘an uncanny capacity to overturn received wisdom of all kinds. Wars and military operations rarely turn out as expected.’

This is obviously about far more than the imaginative geographies that Edward Said exposed so wonderfully well in his Orientalism; as the chapters in the book document in different ways and in different places, these regimes of truth impose and inscribe material economies of violence that, in their turn, enforce those regimes of truth. The relation between the two is not a frictionless machine but a slippery series of precepts, protocols and practices that can (and usually does) come undone – the point that Tarak and Keith sharpen so well – but the dangerous liaison between epistemological violence and physical violence is of cardinal and continuing importance.

For Said, Orientalism entailed two cultural-political performances:

- First, ‘the Orient’ was summoned as an exotic and bizarre space, and at the limit a pathological and even monstrous space: ‘a living tableau of queerness.’

- Second, ‘the Orient’ was constructed as a space that had to be domesticated, disciplined and normalized through a forceful projection of the order it was presumed to lack: ‘framed by the classroom, the criminal court, the prison, the illustrated manual.’

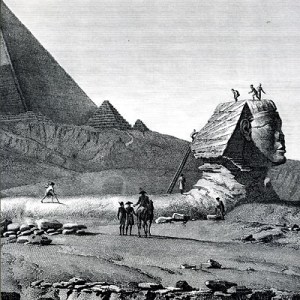

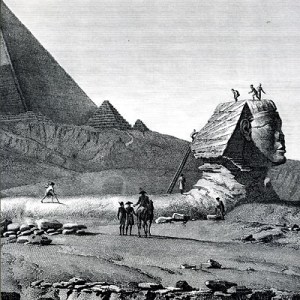

As I’ve said, these performances wrought considerably more than epistemological violence. The Orientalist projection of order was more than conceptual or cognitive, for the process of ordering also conveyed the sense of command and conquest. Said knew this very well, and his critique of Orientalism was framed by a series of wars. Orientalism (1978) opens with the civil war in Lebanon, a place that had a special significance for Said; it was a belated response to his puzzlement at the jubilation on the streets of New York at the Israeli victory in the 1967 and 1973 wars; and it located the origins of a distinctively modern Orientalism in Napoleon’s military expedition to Egypt between 1798 and 1801.

And yet, even as he fastened on the importance of the French invasion and occupation, Said’s focus was unwaveringly on the textual appropriation of ‘ancient Egypt’ by the savants – the engineers, scientists and artists – who accompanied the French army.

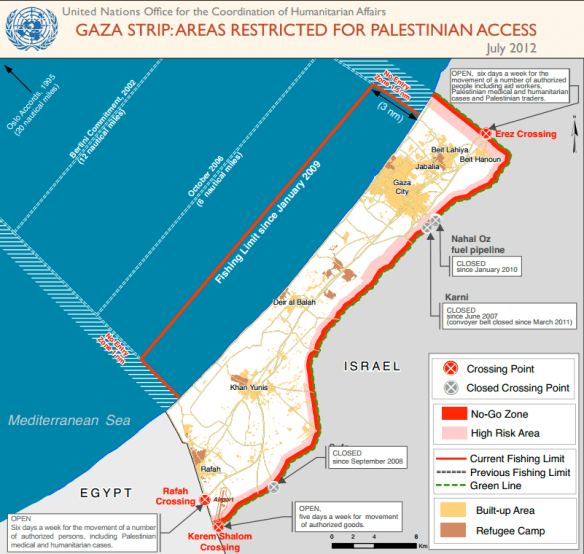

Their collective work was enshrined in the monumental Description de l’Égypte, which Said described as a project ‘to render [Egypt] completely open, to make it totally accessible to European scrutiny’, and so to usher the Orient from what he called ‘the realms of silent obscurity’ into ‘the clarity of modern European science.’ The phrasing is instructive: visuality is a leitmotif of Orientalism. Said repeatedly notes that under its sign ‘the Orient is watched’, that the Orient was always more than tableau vivant or theatrical spectacle, and that the Orientalist technology of power-knowledge was, above all, about ‘making visible’, about the construction ‘of a sort of Benthamite panopticon’ from whose watch-towers ‘the Orientalist surveys the Orient from above, with the aim of getting hold of the whole sprawling panorama’ in every ‘dizzying detail’.

But Napoleon’s military expedition was about more than annexing Egypt as what Said calls ‘a department of French learning’, and its execution inflicted more than cultural violence. In my own contribution to the volume, I tried to go beyond textual appropriations – even as I necessarily relied on an archive that is primarily textual – to trace the changing relations between Orientalism, visuality and military violence from the French occupation of Egypt to the American-led occupations of Afghanistan and Iraq. (There’s an extended version of the essay under the DOWNLOADS tab).

Although I’ve emphasised the historical roots of Said’s critique in this post, I should note that the essays in Orientalism and War are all written by scholars with a clear sense of the continuing, dismally contemporary relations between the two (and Said himself displayed the same sensibility in his brilliant stream of essays on the dispossession of the Palestinian people).

‘When a book comes along that examines what should be obvious yet is utterly under-thought, you have to read it and teach it. This is such a book. It forces us to consider how war is unthinkable without Orientalism, and how Orientalism is unthinkable without war.’ — Cynthia Weber, Professor of International Relations, University of Sussex

‘Orientalism has a history in which projections of superiority and inferiority, fear and desire, repulsion and envy reach extremes that only war can resolve. From Herodotus to Petraeus, Orientalism and war have been cultural bedfellows. Assembling a diversity of views and keenness of inquiry rarely found in a single volume, Tarak Barkawi and Keith Stanski have revitalised the concept of Orientalism to bring a nuanced and complex understanding of how culture has become the killer variable of modern warfare.’ — James Der Derian, Professor of International Studies (Research), Brown University

Contents:

1 Orientalism and War – Tarak Barkawi and Keith Stanski

2 Shocked by War: the non-politics of Orientalism – Arjun Chowdhury

3 American Orientalism at War in Korea and the United States: a hegemony of racism, repression and amnesia – Bruce Cumings

4 Terror, the Imperial Presidency and American Heroism – Susan Jeffords

5 Can the insurgent speak? – Hugh Gusterson

6 Colonial Wars, Postcolonial Specters: the anxiety of domination – Quynh N. Pham and Himadeep R. Muppidi

7 Orientalism in the Machine – Josef Teboho Ansorge

8 Dis/Ordering the Orient: scopic regimes and modern war – Derek Gregory

9 Nesting Orientalisms at war: World War II and the “Memory War” in Eastern Europe – Maria Mälksoo

10 Victimhood as agency: Afghan women’s memoirs – Margaret A. Mills

11 Fanon’s “guerre des ondes”: resisting the call of Orientalism – John Mowitt

12 The Pleasures of Imperialism and the Pink Elephant: Torture, Sex, Orientalism – Patricia Owens

13 Afterword – Patrick Porter