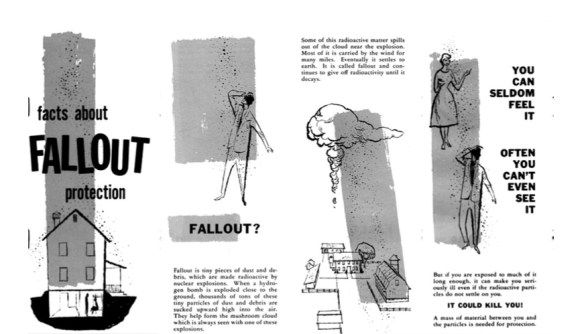

I’ve noted before how one of the most immediate and long-lasting effects of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on American post-atomic culture was an extraordinary sense of vulnerability: hence the steady stream of visuals imagining a nuclear attack on cities like New York and Washington. In The Age of the World Target, Rey Chow writes about

I’ve noted before how one of the most immediate and long-lasting effects of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on American post-atomic culture was an extraordinary sense of vulnerability: hence the steady stream of visuals imagining a nuclear attack on cities like New York and Washington. In The Age of the World Target, Rey Chow writes about

‘…the self-referential function of virtual worlding that was unleashed by the dropping of the atomic bombs, with the United States always occupying the position of the bomber, and other cultures always viewed as the … target fields.’

But in an important sense she couldn’t be more wrong. Here is Paul Boyer in By the Bomb’s Early Light:

‘Physically untouched by the war, the United States at the moment of victory perceived itself as naked and vulnerable. Sole possessors and users of a devastating instrument of mass destruction, Americans envisioned themselves not as a potential threat to other peoples, but as potential victims.’

Or, as Peter Galison put it, writing in Grey Room 4 (2001),

Here stands a new, bizarre, and yet pervasive species of Lacanian mirroring. Having gone through the bomb-planning and bomb-evaluating process so many times for enemy maps of Schweinfurt, Leuna, Berlin, Hamburg, Hiroshima, Tokyo, and Nagasaki, now the familiar maps of Gary, Pittsburgh, New York City, Chicago, and Wichita began to look like them.

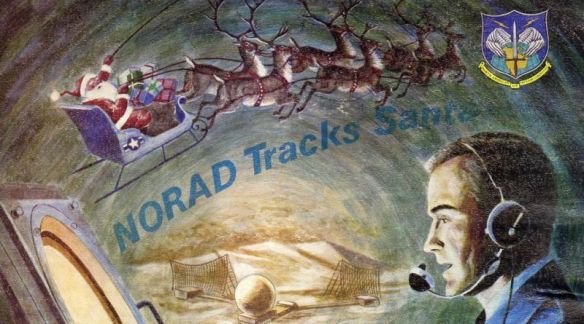

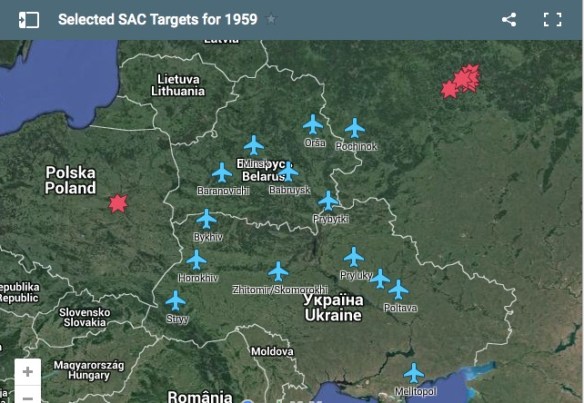

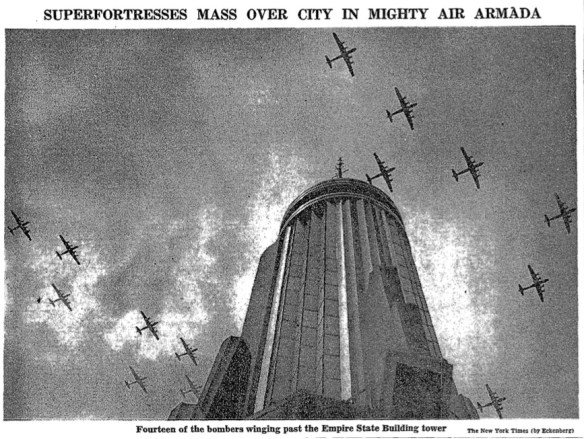

And, as it happens, American cities did become targets – for US Strategic Air Command.

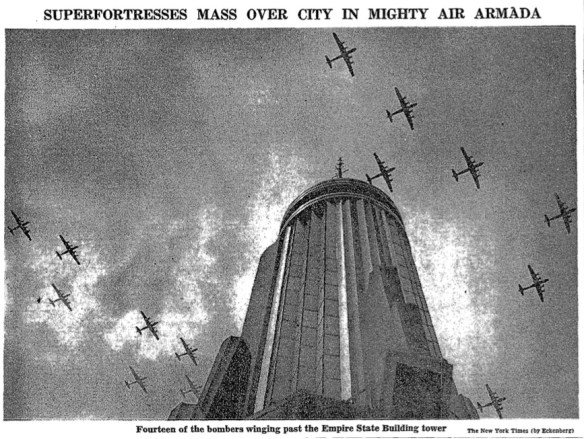

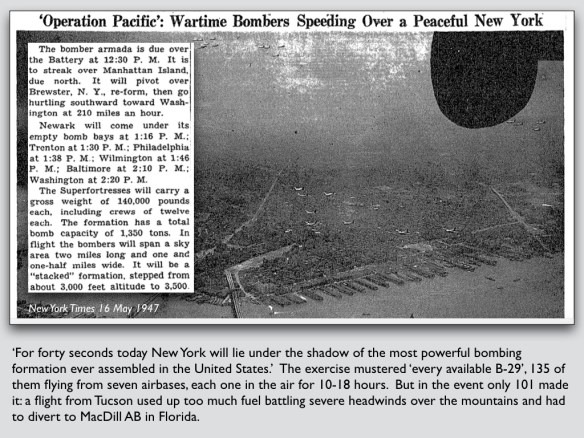

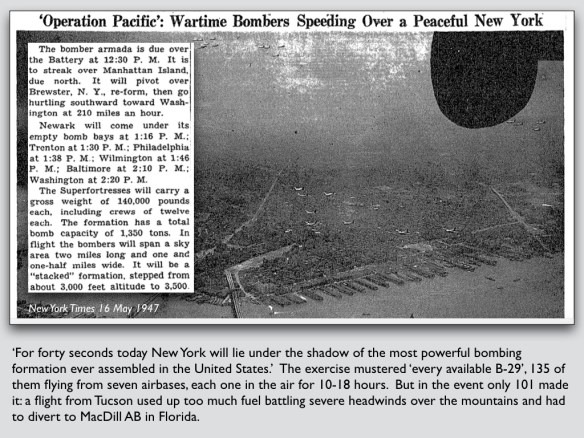

In May 1947 an exercise – ‘Operation Pacific’ – was carried out over the cities of the Eastern seaboard from New York to Washington. Its title was not a tribute to the geospatial intelligence of the US Air Force: General George Kenney, commander of SAC, asked reporters to emphasize that this was, in its way, a peace-keeping mission, ‘an exercise not an attack’, and that the cities involved were ‘objectives’ not targets – so they weren’t candidates for inclusion in the Bombing Encyclopedia of the World…

But it was a disappointment to all concerned:

The public was let down by the lack of spectacle. According to the New York Times,

‘The squadron from Fort Worth missed the rendezvous by twenty minutes… [which] destroyed the effect of a mass bombing the main-in-the-street had been led to expect…

‘Check-up from the Battery to the Yonkers line indicated that public disappointment was general if not unanimous. Brooklyn, Queens, Staten Island and the Bronx, where hundreds of thousands turned out on the streets and on rooftops, alike reported that nowhere was there acclaim or enthusiasm, except in school-yards and other places where small-fry congregated.’

The senior brass were even more dismayed. Philip Meilinger described it as a ‘sad situation’ so ‘in August SAC tried again, against Chicago, but the performance was even worse.’

In 1948 Kenney was replaced by another veteran, Curtis LeMay, who was determined to lick SAC into shape – and preferably far from the watchful eyes of the public. Three months after he assumed command, LeMay ordered a bombing exercise against a target field near Wright-Patterson AFB at Dayton, Ohio. In To kill nations, Edward Kaplan bleakly observes:

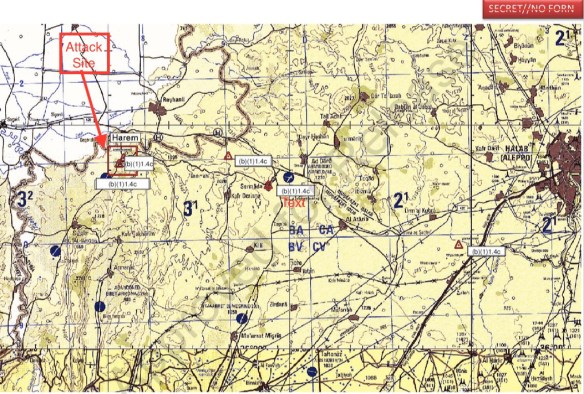

‘To simulate the inaccurate maps of many Soviet targets, [LeMay] gave the bomber crews 1930s-era charts. As LeMay suspected, because of equipment failures when taken up to operational altitudes [until then the crews had been flying at 15,000 not 40,000 feet] and gaps in training, the crews utterly failed to accomplish the mission. Everything that could go wrong, did. Not one crew would have bombed the target successfully. Of 303 runs made at the target, the circular error probable was 10,100 feet, outside the effective radius of a Hiroshima-size weapon.’

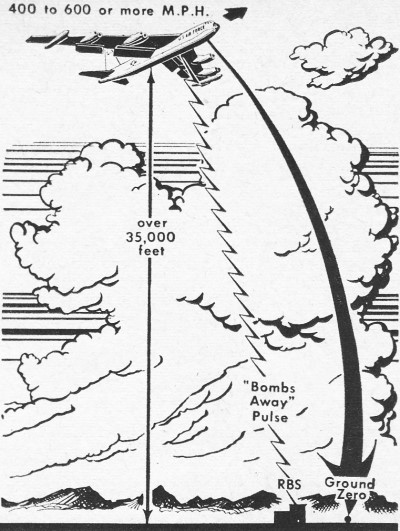

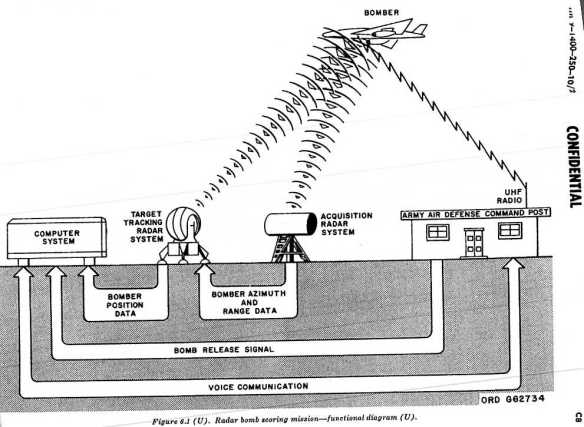

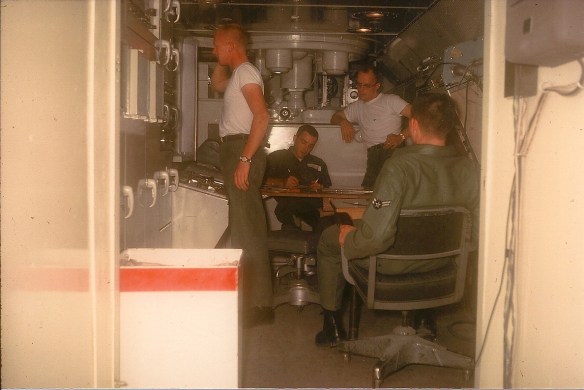

LeMay ordered an intensive programme of training and practice. A key resource was radar bomb scoring (see also here):

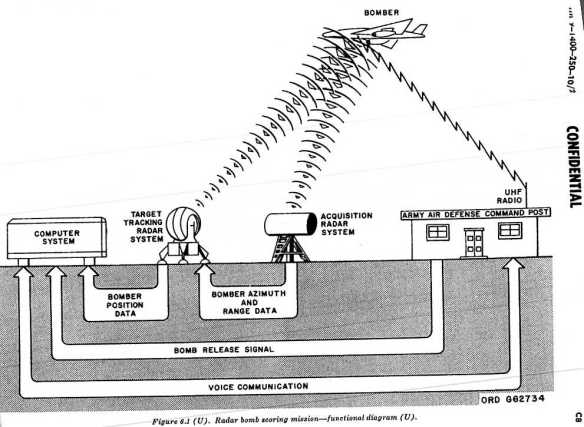

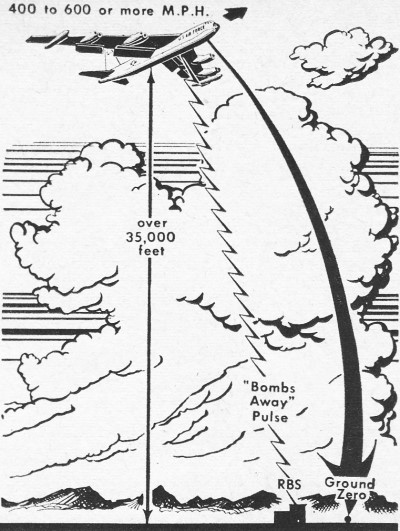

According to Sigmund Alexander, in 1947 SAC completed more than 12,000 radar bomb scoring runs; the next year the number soared to 28,049, an average of about 76 runs per day. In 1956 Popular Electronics – from which I’ve borrowed the diagram above – explained the procedure:

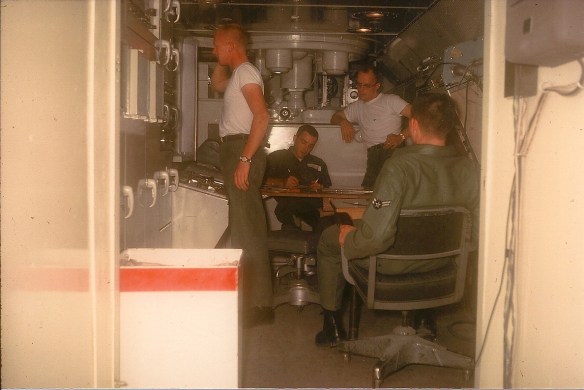

‘Airmen cried “Bombs away!” but instead of devastating blasts the only visible evidence of the crew’s ability to destroy a target was cryptic electronic signals observed by technicians at work inside a special radar station.… When the airplane signals “Bombs away!” a radar pulse is sent from the bomber to the ground station, known as a Radar Bomb Scoring (RBS) unit. The station is built inside a mobile van. A Mobile Radar Control System (MSQ) in the van uses the received pulses to track the course of the bomber, while computers determine the accuracy of “hits.” Blips across a radarscope represent the flight path of the plane. The results of the scoring computer are shown as a thin red line traced by an electronic “pen” on a sheet of blank paper. With this data, the RBS group working in the van knows just where the “bomb” hits.’

This was virtual bombing, and it was a highly skilled affair. Colonel Francis Potter recalls:

These practice bomb runs … required a large amount of skill between the radar operator and the navigator to correctly identify the necessary check points to arrive at “bombs away” time on the correct heading and on time. The co-pilot would normally contact the bomb site via VHF (Very High Frequency) radio and relay the required information…. If memory serves me, we reported crew number, operator’s name, target designator, altitude, and type of release, IP (initial point, where you started the bomb run) and direction of flight at the time of “release.” This info would be repeated to us and confirmed. Our position would be reported when over the IP point, usually some 50-60 miles out. After passing this point, directional control of the aircraft would be passed to the radar operator, who could tie it into his sighting system, and using the auto pilot small directional controls would be made. At the proper time prior to “release”, a continuous radio “tone” would be emitted which would alert the scoring site that release was imminent. At the proper time and place, the tone would stop. This was the release point. The co-pilot would announce to the site “bombs away.” The site would then “score” the probable impact point, using wind drift and other factors that apply. After a few suspenseful moments, the site would contact us with an encoded score. We could de-code this and find that our bomb had hit XXX feet in which direction and distance from the intended point of impact. Obviously close to the desired spot was always the hoped for results. We would then return to the same IP or another in the same area and perform another run. We often stayed at the same site for several hours running one practice run after another. The scores the operator obtained would be catalogued and a probable CE (circular error) would be determined. This would be determined for each set of bomb runs and would be considered in determining the “over-all” accuracy of the individual operator.

But aircrews soon became over-familiar with the fixed targets on designated bombing ranges. Here is Don Ross:

When the aircrew was scheduled to simulate bombing a target in our area (we had about 15 or 20 targets, which could be a barn, a building, a cross roads, a fence post, or just coordinates on a map), they would contact us and we would position the target they were going after on our plotting board, track them in and measure how well they did….

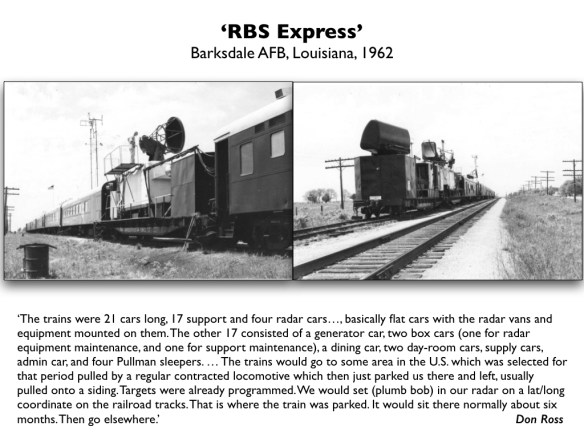

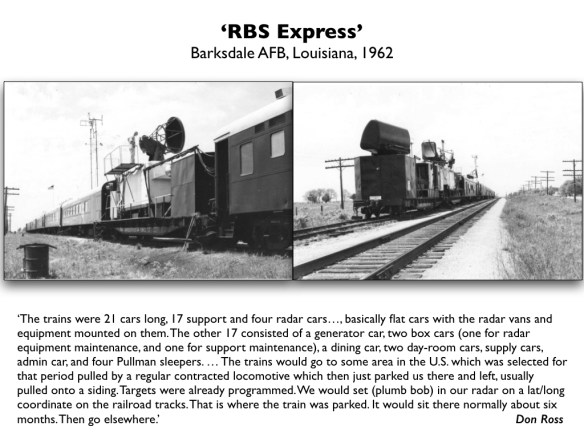

Well, the aircrews flew against these targets so often, that they became good at hitting them, Damn good. So good, they could do it in their sleep. So, to ensure they were able to actually keep remembering how to set up and find the target, SAC set up even more targets all over the country. As they were well beyond the reach of our detachments, each Squadron was given a train…

Starting in 1961, three special trains were fitted with the necessary equipment (see below; more images here and here):

Targets would now move from city to city onboard the ‘RBS Express’:

During the wars in Korea and Vietnam, radar bomb scoring was reverse-engineered to guide bombers to their targets (see my discussion of ‘Skyspot‘ in ‘Lines of Descent: DOWNLOADS tab; you can also find much more in this evaluation report from Vietnam here).

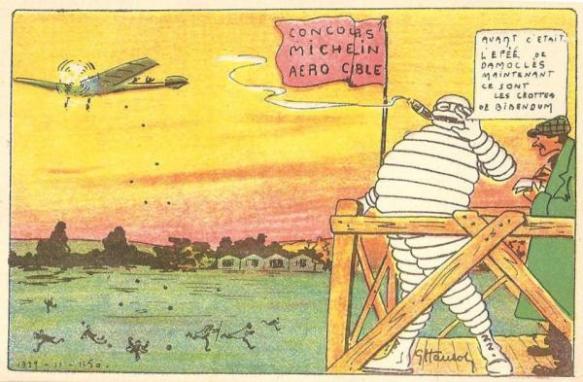

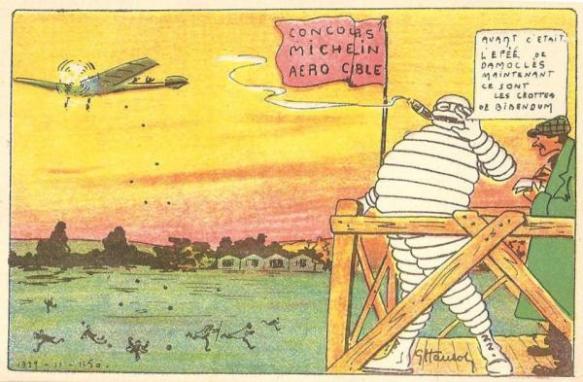

But here’s the thing. In a previous post I described how the Michelin brothers established a bombing competition (the Aero-Cible or Air Target Competition) in 1911 to convince politicians and the public that bombing was the future of military aviation – and, no doubt, that Michelin was the company to produce the aircraft:

The results, incidentally, were not especially encouraging:

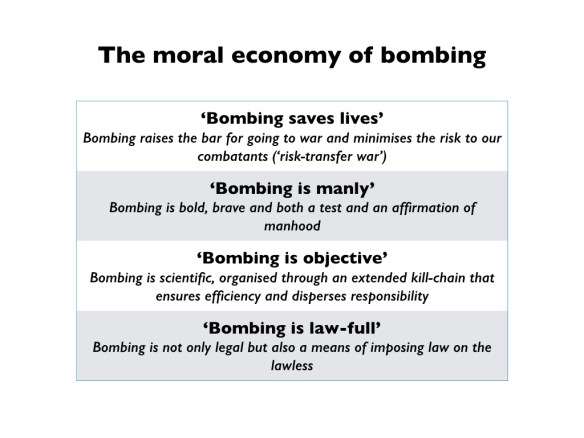

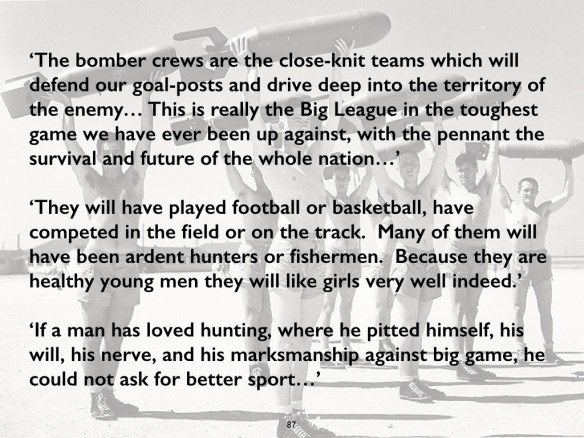

The idea of bombing as a ‘sport’ figured in my subsequent discussion of the moral economy of bombing. Here, for example, is John Steinbeck on US bomber crews in the Second World War in Bombs Away!

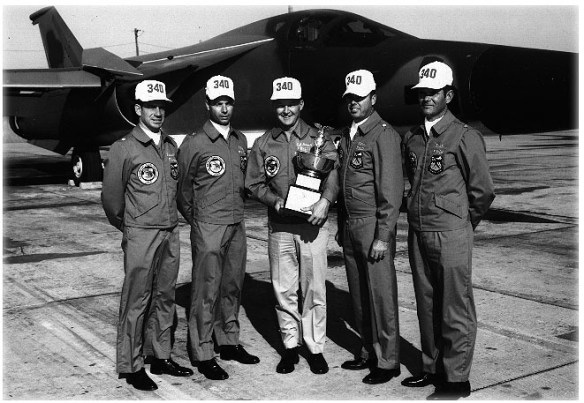

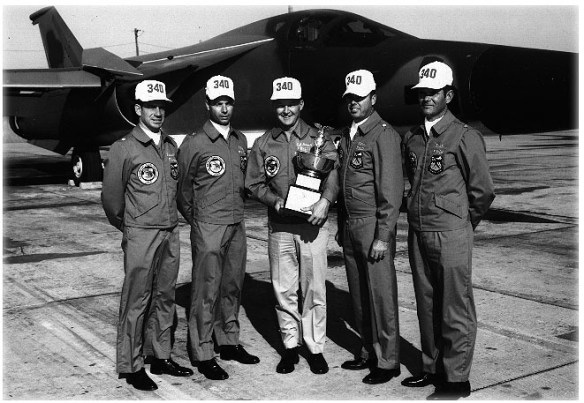

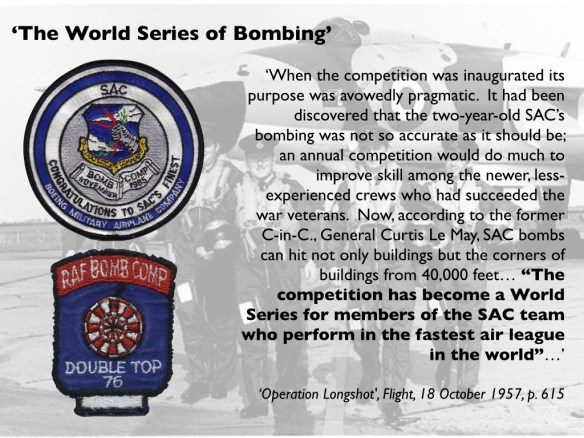

Radar bomb scoring carried this extraordinary metaphoric into the Cold War with Strategic Air Command’s inaguration of what became known as ‘Bomb Comp’, held between 1948 and 1992. Here are the lucky winners in 1970, the 8th Air Force’s 340th Bomb Group – note the trophy and the baseball caps.

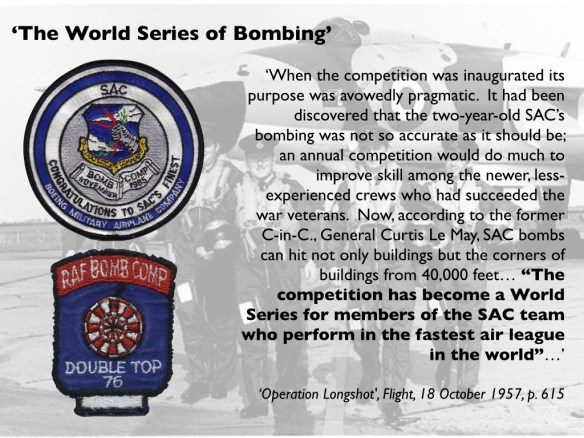

This often involved competitions with Britain’s Royal Air Force, and it became known not as Steinbeck’s ‘Big League’ but as ‘the World Series of Bombing’:

You might be able to blow it up – but you couldn’t make it up.