As I work on turning my Beirut talk on drone strikes in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) into a long-form version – which includes a detailed and critical engagement with Giorgio Agamben‘s characterisation of the state/space of exception – I’ll post some of the key arguments here. But for now, two important developments.

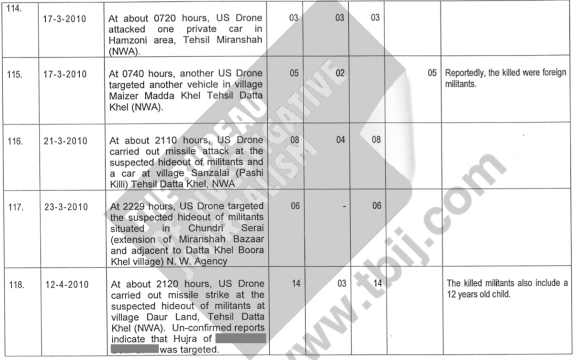

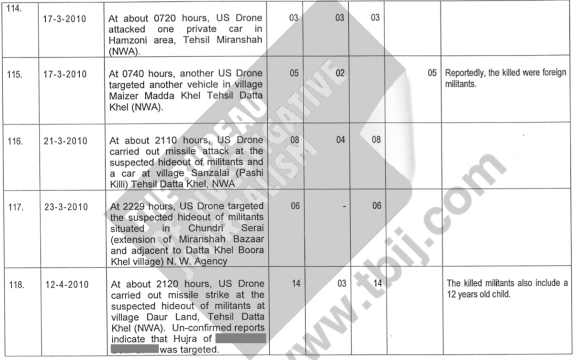

First, the Bureau of Investigative Journalism has just published a list of 330 drone strikes between 2006 and July 2013 (data for the five strikes that took place in 2007 are missing) compiled by the Pakistan government (see extract above); this is an update of a partial release from the Bureau last summer. The source is a series of reports filed each evening by Political Agents in the field to the FATA secretariat, and while it’s not a comprehensive listing – and Islamabad relies on other sources too – the document closely follows the Bureau’s own database compiled from other independent sources. It also allows for a more accurate mapping of the strikes – more to come on this.

But one key difference between the list and the Bureau’s database is that, following the election of Obama, the official reports no longer attempted to classify the victims as combatants or civilians: and the coincidence may not be coincidental. According to Chris Woods,

‘One of my sources, a former Pakistani minister, has indicated that local officials may have come under pressure to play down drone civilian deaths following the election of Barack Obama. It’s certainly of concern that almost all mention of non-combatant casualties simply disappears from this document after 2009, despite significant evidence to the contrary.’

One of the most egregious omissions is the drone strike on 24 October 2012 that killed Mamana Bibi, a grandmother tending the fields with her grandchildren. The case was documented extensively by Amnesty International and yet, as the Bureau notes, while the date and location of the strike is recorded the report from the political agent is remarkably terse and makes nothing of her evident civilian status.

‘If a case as well-documented as Mamana Bibi’s isn’t recorded as a civilian death, that raises questions about whether any state records of these strikes can be seen as reliable, beyond the most basic information,’ said Mustafa Qadri, a researcher for Amnesty International…. ‘It also raises questions of complicity on the part of the Pakistan state – has there been a decision to stop recording civilians deaths?’

These are important questions, and in fact one of the central objectives of my own essay is to document the close, covert co-operation between the US and Pakistani authorities: what I called, in an earlier post, dirty dancing, trading partly on Jeremy Scahill’s inventory of ‘dirty wars’ and partly on Joshua Foust‘s calling out of the ‘Islamabad drone dance’.

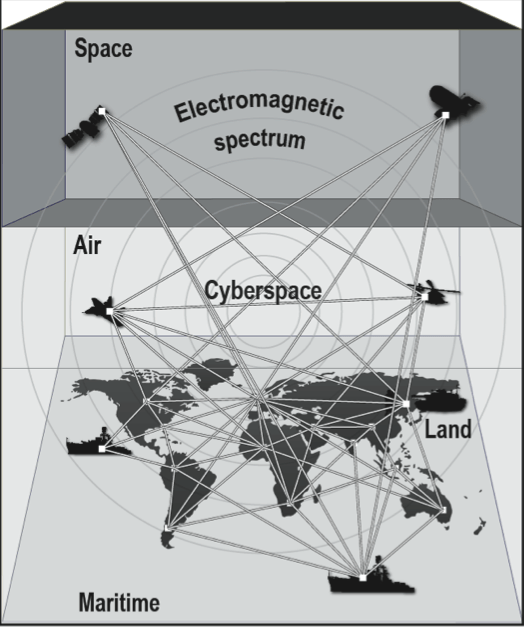

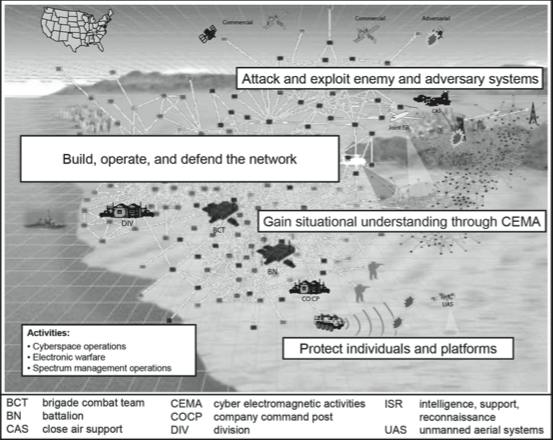

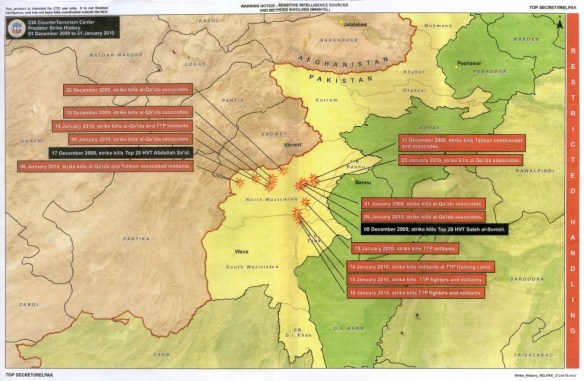

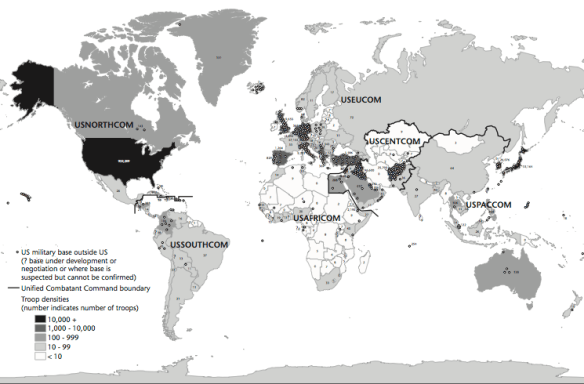

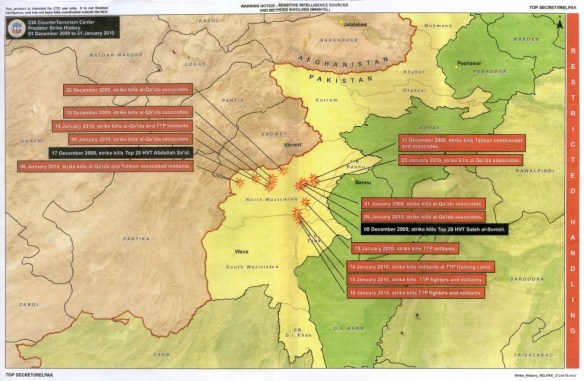

We now know that this collaboration continued at the very least until late 2011. The CIA’s Counterterrorism Center routinely prepared reports that included maps (see below) and pre- and post-strike imagery that were briefed by the Deputy Director to Husain Haqqani, the Pakistani ambassador in Washington, and subsequently transmitted to Islamabad.

And consistent with the reports from Political Agents to the FATA Secretariat, Greg Miller and Bob Woodward note that in these briefings:

Although often uncertain about the identities of its targets, the CIA expresses remarkable confidence in its accuracy, repeatedly ruling out the possibility that any civilians were killed. One table estimates that as many as 152 “combatants” were killed and 26 were injured during the first six months of 2011. Lengthy columns with spaces to record civilian deaths or injuries contain nothing but zeroes.

The collaboration is important, because it has major implications for how one thinks about the Federally Administered Tribal Areas as a ‘space of exception’: there are multiple legal regimes through which the people who live in these borderlands are knowingly and deliberately ‘exposed to death’, as Agamben would have it. More on this later, but for now there is a second, more substantive point to be sharpened.

I’ve previously emphasised that the people of FATA are not only ‘living under drones‘, as the Stanford/NYU legal team put it last year, but also under the threat of air strikes from the Pakistan Air Force. Last week the PAF resumed air strikes against leaders of the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) in North Waziristan, using first F-16 aircraft and then helicopter gunships to attack what were described as ‘eight major targets’ in the villages of Mir Ali (Hamzoni, Issori, Khadi and Nawana). Although the Air Force described the operation as a ‘blitz’, it initially claimed that only two people were killed. A different story soon emerged.

According to Pakistan’s International News, the air raids started just before midnight on 20 January, and people ‘left their homes in desperation and spent the night in the open along with children when the jets started bombing.’

There were conflicting reports about the identity of those killed. Military authorities said all the 40 people killed in the overnight aerial strikes were hardcore militants or their relatives and family members.

However, tribesmen in Mir Ali subdivision insisted that some local villagers, including women, children and elderly people, were also killed in the bombing by the PAF’s fighter aircraft and Pakistan Army’s helicopter gunships as residential areas were attacked.

Several days later there were reports of hundreds – even thousands – of people fleeing the area in anticipation of continuing and intensifying military operations. On 25 January the Express Tribune reported:

“Most of the families of Mir Ali Bazaar and adjacent areas have been leaving,” Abdullah Wazir, a resident of Spin Wam told The Express Tribune, adding, “women and children have been leaving with household materials, but livestock and larger items of belongings are being abandoned by these families.”

“It is difficult to find shelter in Bannu,” said Janath Noor, aged 38, who travelled there with her family. “There are problems at home and here in Bannu too.” She added that the families were forced to act independently as the political administrations in North Waziristan and Bannu have not made arrangements for the fleeing families. Some families reportedly spent the night under the open sky in Bannu town, waiting for any available shelter.

Some IDPs have also faced problems such as harassment at the hands of the police, requests for bribes, soaring rates of transport from Mir Ali and inflated rents for houses in Bannu. Some families, suspected of being militants, have had problems finding accommodation in Bannu district.

By 27 January the government estimated that 8,000 people had arrived in Bannu, while many others unable to find shelter and unwilling to sleep in the open had hone on to Peshawar and elsewhere. But the head of the FATA Disaster Management Authority declared that ‘No military operation has been announced in the tribal area so there are no instructions to make arrangements for the internally displaced people.’

Most local people were clearly sceptical about that and, certainly, there were authoritative claims that Pakistan was being put ‘on a war footing’ to counter the surging power of the TTP. In the same week that the air strikes were launched, Islamabad promulgated an amended Protection of Pakistan Ordinance (PPO), modelled on the imperial Rowlatt Act of 1919, that included provisions for secret courts, greater shoot-to-kill license for the police, house raids without warrants and the detention of terror suspects without charge. Rana Sanaullah, Minister for Law, Parliamentary Affairs and Public Prosecution in the Punjab and a close confidant of Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, told the Guardian: ‘I think what will be done will be no worse than what has happened in Guantánamo Bay.’ Not surprisingly, he also offered support for the US drone strikes:

‘We believe that drone attacks damage the terrorists, very much… Inside, everyone believes that drone attacks are good; but outside, everyone condemn because the drones are American.’

And, as I’ll try to show in a later post, it’s a different inside/outside indistinction that plays a vital role in producing the FATA as a space of exception.