Fred Kaplan has an interesting essay on the history and use of armed drones by the United States at MIT Technology Review: ‘The world as free-fire zone‘ (June 2013). Kaplan provides a telling critique of Obama’s May statement about the conduct of targeted killings (though that doesn’t of course exhaust what the military uses UAVs for), but his discussion is muddied by what he says about Vietnam – and what he doesn’t.

The title of the essay invokes a notorious tactic deployed by the United States in South Vietnam: the creation of free-fire, free-strike or what the Air Force called free-bomb zones (the name was changed in 1967 to ‘specified fire zones’ for PR purposes, though what was specified was the zone not the fire). This is how historian Bernd Greiner summarises the policy in War without fronts: the USA in Vietnam (2007, trans. 2009):

The title of the essay invokes a notorious tactic deployed by the United States in South Vietnam: the creation of free-fire, free-strike or what the Air Force called free-bomb zones (the name was changed in 1967 to ‘specified fire zones’ for PR purposes, though what was specified was the zone not the fire). This is how historian Bernd Greiner summarises the policy in War without fronts: the USA in Vietnam (2007, trans. 2009):

‘License to destroy and annihilate on a large-scale applied unrestrictedly in the so-called “Free Fire Zones”. Set by the South Vietnamese authorities – either the civil administration or the commanders of an Army corps or division – the US forces operated within them as though outside the law: “Prior to entrance into the area we as soldiers were told all that was left in the area after civilian evacuation were Viet Cong and thus fair game.” Virtually all recollections of the war contain such a statement or something similar, simultaneously referring to the fact that anyone who did not want to be evacuated had forfeited the right to protection, since in the Free Fire Zones the distinction between combatant and non-combatant was a prior lifted.’

Matters were not quite so simple, at least in principle, since (as Nick Turse notes in Kill anything that moves: the real American war in Vietnam (2013)), ‘the “free-fire” label was not quite an unlimited license to kill, since the laws of war still applied in these areas.’ And yet, as both Greiner and Turse show in considerable detail (and I’ll have more to say about this in another post), in practice those laws and the rules of engagement were serially violated. Whatever the situation in Vietnam, however, it’s surely difficult to extend this – as Kaplan wants to do – to US policy on targeted killings. Invoking the Authorization for Use of Military Force passed by Congress on 14 September 2001 (as Obama does himself), Kaplan writes:

‘This language is strikingly broad. Nothing is mentioned about geography. The premise is that al-Qaeda and its affiliates threaten U.S. security; so the president can attack its members, regardless of where they happen to be. Taken literally, the resolution turns the world into a free-fire zone‘ (my emphasis).

A couple of years ago Tom Engelhardt also wrote about Obama hardening George W. Bush’s resolve to create a ‘global free-fire zone’. Kaplan’s criticism of the conditions that the Obama administration now claims restrict counter-terrorism strikes is, I think, fair – though much of what he says derives directly from a draft Department of Justice memorandum dated 8 November 2011 on ‘the use of lethal force in a foreign country outside the area of active hostilities against a U.S. citizen who is a senior operational leader of al-Qa’ida or an associated force’ rather than Obama’s wider speech on counter-terrorism on 23 May 2013 or the ‘fact sheet on policy standards and procedures’ that accompanied it. But they are closely connected, and Kaplan’s objections have real substance.

First, the Obama administration insists that the threat posed to the United States must be ‘imminent’, yet since the threat is also deemed to be continuing ‘a broader concept of imminence’ is required that effectively neuters the term.

Second, apprehension of the suspect must be unfeasible, yet the constant nature of the threat means that the ‘window of opportunity’ can always be made so narrow that ‘kill’ trumps ‘capture’.

But what of Obama’s third condition: that ‘before any strike is taken, there must be near-certainty that no civilians will be killed or injured’? Kaplan accepts that this is a ‘real restriction’. Critics of the programme differ on how successful it has been in practice, and supporters like Amitai Etzioni have turned ‘civilian’ into a weasel word that means whatever they want it to mean (which is not very much). Still, the most authoritative record of casualties – which I take to be the Bureau of Investigative Journalism in London – clearly shows that civilian deaths in Pakistan (at least) have fallen considerably from their dismal peak in 2009-10. Whatever one makes of all this, however, it hardly turns the world into a ‘free-fire zone’. The war machine will continue to be unleashed outside declared war zones (or what Obama also called ‘areas of active hostilities’, which may or may not mean the same thing), and Obama and his generals will continue to conjure a battlespace that is global in extent. But if we take the President at his word – and I understand the weight that conditional has to bear – military violence may occur everywhere but not anywhere: ‘We must define our effort not as a boundless “global war on terror” – but rather as a series of persistent, targeted efforts to dismantle specific networks of violent extremists that threaten America.’

The question is whether we can take the President at his word. As Glenn Greenwald points out, ‘Obama’s speeches have very little to do with Obama’s actions’. Tom Junod says much the same about what he continues to call the Lethal Presidency: ‘When a man is as successful in fusing morality and rhetoric as Barack Obama, there’s always a tendency to think that the real man exists in his words, and all he has to do is find a way to live up to them.’ Performativity is not only conditional, as it always is, but in this case also discretionary.

Kaplan also refers to a notorious metric from the Vietnam war: the body-count. As James Gibson patiently explains in his brilliant critique of The perfect war: technowar in Vietnam (1986), this was one of the central mechanisms in US Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara’s attempt to wage an appropriately Fordist war (he went to the Pentagon from being President of the Ford Motor Company). The body-count can be traced back to the Korean War, but it came into its own in Vietnam where it was supposed to be the key metric of success – bizarrely, even of productivity – in a ‘war without fronts’ where progress could not be measured by territory gained. Here too Turse is illuminating on the appalling culture that grew up around it, including the inflation (and even invention) of numbers, the body-count competitions, and the scores and rewards for what today would no doubt be called ‘excellence in killing’.

Kaplan also refers to a notorious metric from the Vietnam war: the body-count. As James Gibson patiently explains in his brilliant critique of The perfect war: technowar in Vietnam (1986), this was one of the central mechanisms in US Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara’s attempt to wage an appropriately Fordist war (he went to the Pentagon from being President of the Ford Motor Company). The body-count can be traced back to the Korean War, but it came into its own in Vietnam where it was supposed to be the key metric of success – bizarrely, even of productivity – in a ‘war without fronts’ where progress could not be measured by territory gained. Here too Turse is illuminating on the appalling culture that grew up around it, including the inflation (and even invention) of numbers, the body-count competitions, and the scores and rewards for what today would no doubt be called ‘excellence in killing’.

But what Kaplan has in mind is not quite this, but the central, absurdist assumption that there is a direct relationship between combatants killed and military success:

‘It is worth recalling the many times a drone has reportedly killed a “number 3 leader of al-Qaeda.” There was always some number 4 leader of al-Qaeda standing by to take his place. It’s become a high-tech reprise of the body-count syndrome from the Vietnam War — the illusion that there’s a relationship between the number of enemy killed and the proximity to victory.’

How else can we interpret John Nagl‘s tangled celebration (on Frontline’s ‘Kill/Capture’) of the importance of targeted killing for counterinsurgency and counter-terrorism?

‘We’re getting so good at various electronic means of identifying, tracking, locating members of the insurgency that we’re able to employ this almost industrial-scale counterterrorism killing machine that has been able to pick out and take off the battlefield not just the top level al Qaeda-level insurgents, but also increasingly is being used to target mid-level insurgents.’

Peter Scheer draws a distinction between the two moments in Nagl’s statement that helps clarify what he presumably intended (though Scheer is writing more generally):

‘The logic of warfare and intelligence have flipped, each becoming the mirror image of the other. Warfare has shifted from the scaling of military operations to the selective targeting of individual enemies. Intelligence gathering has shifted from the selective targeting of known threats to wholesale data mining for the purpose of finding hidden threats.’

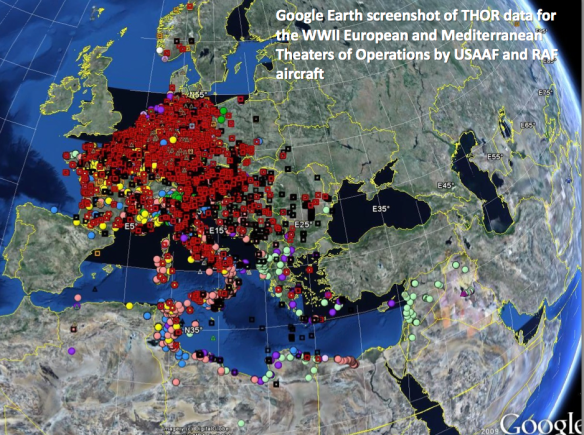

In other words, the scale of intelligence has become industrial (or more accurately perhaps, post-industrial: see here), far exceeding the scale of intelligence available in Vietnam [though see here for a discussion of the connections between McNamara’s data-driven war and today’s obsession with Big Data, and here and here for an outline of the ‘security-industrial complex’], whereas the scale of killing has clearly contracted from what most certainly was industrial-scale killing in Vietnam. Yet the networked connections between the two reveal the instantiation of the same driving logic of technowar in a radically new ‘war without fronts’.

For all these intimation of Vietnam, however, the genealogy of the drone with which Kaplan begins his essay is resolutely post-Vietnam (or at any rate outside it). And this, I think, is a mistake.

Technological history is shot through with multiple sources of inspiration and no end of false starts, and usually has little difficulty in assembling a cast of pioneers, precursors and parallels, so I’m not trying to locate a primary origin. Ian Shaw‘s account of the rise of the Predator (more from J.P. Santiago here) homes in on the work of Israeli engineer Abraham Karem, who built his first light-weight, radio-controlled ‘Albatross’ (sic) in his garage in Los Angeles in 1981.

He may have built the thing in his garage, but Karem was no hobbyist; he was a former engineering officer in the Israeli Air Force who had worked for Israel Aircraft Industries, and by 1971 he had set up his own company to design UAVs. Neither the Israeli government nor the Israeli Air Force was interested, so Karem emigrated to the United States. The Albatross was swiftly followed by the Amber, which was also radio-controlled, and by 1988 with DARPA seed-funding Karem’s prototype was capable of remaining aloft at several thousand feet for 40 hours or more. But fitting hi-tech sensor systems into such a small, light aircraft proved difficult and both the US Navy and the Army balked at the project. Karem set about developing a bigger, heavier and in many ways less advanced version for a putative export market: the GNAT-750.

This was a desperate commercial strategy that didn’t save Karem’s company, Leading Systems Inc., from bankruptcy. But it was a sound technical strategy. In 1990 General Atomics bought the company and the development team, and when the CIA was tasked with monitoring the rapidly changing situation in the Balkans it purchased two GNAT-750s (above) for the job. They were modified to allow for remote control via a satellite link (the first reconnaissance missions over Bosnia in 1995 were managed by the Air Force and controlled from Albania): the new aircraft was re-named the Predator.

It’s a good story – and you can find a much more detailed account by Richard Whittle in ‘The man who invented the Predator’ at Air & Space Magazine (April 2013) here – but in this form it leaves out much of the political in-fighting. The second part of Ian’s narrative turns to the role of the Predator in the development of the CIA’s counter-terrorism campaign, and while he notes the enlistment of the US Air Force – ‘ultimately, the CIA arranged for Air Force teams trained by the Eleventh Reconnaissance Squadron at Nellis Air Force Base [Indian Springs, now Creech AFB] to operate the agency’s clandestine drones’ – he doesn’t dwell on the ‘arranging’ or the attitude of the USAF to aircraft without pilots on board.

Kaplan does, and his story starts earlier and elsewhere:

‘The drone as we know it today was the brainchild of John Stuart Foster Jr., a nuclear physicist, former head of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (then called the Lawrence Radiation Laboratory), and — in 1971, when the idea occurred to him — the director of defense research and engineering, the top scientific post in the Pentagon.’

Foster was a hobbyist – he loved making model aircraft – and thought it ought to be possible to capitalise on his passion: ‘take an unmanned, remote-controlled airplane, strap a camera to its belly, and fly it over enemy targets to snap pictures or shoot film; if possible, load it with a bomb and destroy the targets, too.’ Two years later DARPA had overseen the production of two prototypes, Praeire [from the Latin, meaning both precede and dictate] and Caler [I have no idea], which were capable of staying aloft for 2 hours carrying a 28 lb payload. At more or less the same time, the Pentagon commissioned a study from Albert Wohlstetter, a former RAND strategist, to identify new technologies that would enable the US to respond to a Soviet invasion of Western Europe without pressing the nuclear button. ‘Wohlstetter proposed putting the munitions on Foster’s pilotless planes and using them to hit targets deep behind enemy lines, Kaplan explains, ‘Soviet tank echelons, air bases, ports.’ By the end of the decade the Pentagon was testing ‘Assault Breaker’ and according to Kaplan ‘something close to Foster’s vision finally materialized in the mid-1990s, during NATO’s air war over the Balkans, with an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) called the Predator.’

But the use of the mid-altitude, long-endurance (‘MALE’ – really) drones remained largely the preserve of the CIA because the senior officer corps of the Air Force was hostile to their incorporation:

‘All this changed in 2006, when Bush named Robert Gates to replace Donald Rumsfeld as secretary of defense. Gates came into the Pentagon with one goal: to clean up the mess in Iraq… He was particularly appalled by the Air Force generals’ hostility toward drones. Gates boosted production; the generals slowed down delivery. He accelerated delivery; they held up deployment. He fired the Air Force chief of staff, General T. Michael Moseley (ostensibly for some other act of malfeasance but really because of his resistance to UAVs), and appointed in his place General Norton Schwartz, who had risen as a gunship and cargo-transport pilot in special operations forces… and over the next few years, he turned the drone-joystick pilots into an elite cadre of the Air Force.’

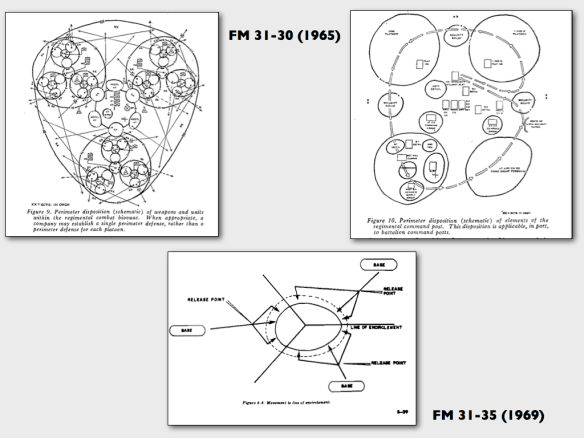

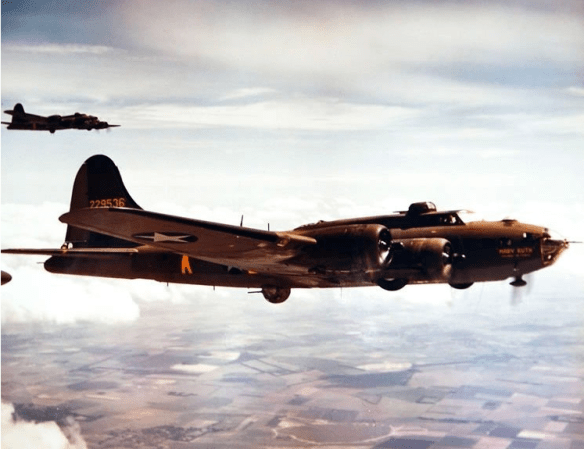

These are both important narratives, which help to delineate multiple lines of descent, but my own inclination is to push the story back and to move it outside the North Atlantic. It’s not difficult to find precedents for UAVs around the time of the First World War – I’ve discussed some of them here – and towards the end of the Second World War America attempted to develop remote-controlled bombers to use against Germany (see ‘Project Aphrodite’ here and here). But if we focus less on the object – the aircraft – and more on its dispositions and the practices mobilised through the network in which it is embedded (as Kaplan’s references to ‘free-fire zones’ and ‘body counts’ imply) then I think here Vietnam is the place to look. For as I’ve argued in ‘Lines of descent’ (DOWNLOADS tab), not only did the Air Force experiment with surveillance drones over North Vietnam, as Ian briefly notes in his own account, but the US military developed a version of ‘pattern of life analysis’ and a sensor-shooter system that would prove to be indispensable to today’s remote operations. Seen like this, they confirm that we are witnessing a new phase of technowar in exactly the sense that Gibson used the term: except that now it has been transformed into post-Fordist war and, to paraphrase David Harvey, ‘flexible annihilation’.

News of an important new book that feeds directly into my new project on medical-military machines and casualties of war, 1914-2014: Steven Casey‘s When Soldiers Fall: How Americans Have Confronted Combat Losses from World War I to Afghanistan (OUP, January 2014). My own project is concerned with the precarious journeys of those wounded in war-zones (combatants and civilians) rather than those killed and the politics of ‘body-counts’, but Casey’s work presents a vigorous challenge to the usual assumptions about public responses to combat deaths:

News of an important new book that feeds directly into my new project on medical-military machines and casualties of war, 1914-2014: Steven Casey‘s When Soldiers Fall: How Americans Have Confronted Combat Losses from World War I to Afghanistan (OUP, January 2014). My own project is concerned with the precarious journeys of those wounded in war-zones (combatants and civilians) rather than those killed and the politics of ‘body-counts’, but Casey’s work presents a vigorous challenge to the usual assumptions about public responses to combat deaths: