I’ve been tracing commentaries on Kurt Lewin‘s classic essay on what we might call the topological phenomenology of the battlefield, published in 1917 as ‘Kriegslandschaft‘ (‘landscape of war’ or, loosely, ‘warscape’), which was based on his experience on the Western Front in the First World War. I’ve been particularly interested in his account of the way in which an ordinary landscape is transformed by war.

William Boyd captured what I have in mind in The new confessions:

‘Take an idealized image of the English countryside – I always think of the Cotswolds in this connection… You know exactly the sort of view it provides. A road, some hedgerowed lanes, a patchwork of fields, a couple of small villages… The eye sweeps over these benign and neutral features unquestioningly.

‘Now, place two armies on either side of this valley. Have them dig in and construct a trench system. Everything in between is suddenly invested with new sinister potential: that neat farm, the obliging drainage ditch, the village at the crossroads become key factor sin strategy and survival. Imagine running across those intervening fields in an attempt to capture positions on that gentle slope opposite… Which way will you go? What cover will you seek? … Try it the next time you are on a country stroll and see how the most tranquil scene can become instinct with violence. It only requires a change in point of view.’

I’ve discussed this passage before, but what interested Lewin was the way in which the landscape changed for the soldier as he approached the front, moving from a ‘landscape of peace’ to a ‘landscape of war’ – what he described as the production of a ‘directive landscape’. You can find an English translation here, but it’s behind a paywall I can’t scale: Art In Translation, 1 (2)( 2009) 199-209. (If anybody has a ladder, please let me know).

I’ve discussed this passage before, but what interested Lewin was the way in which the landscape changed for the soldier as he approached the front, moving from a ‘landscape of peace’ to a ‘landscape of war’ – what he described as the production of a ‘directive landscape’. You can find an English translation here, but it’s behind a paywall I can’t scale: Art In Translation, 1 (2)( 2009) 199-209. (If anybody has a ladder, please let me know).

En route, I stumbled on a fascinating PhD thesis by Greer Crawley, Strategic Scenography: staging the landscape of war (University of Vienna, 2011). I’ve discussed various conceptions of the ‘theatre of war’ several times before (see for example here, here and here), but Greer provides a much fuller and richer account. Here is the abstract:

This dissertation is concerned with the construction of ‘theatres of war’ in the target landscapes of 20th century military conflict in Europe and America. In this study of the scenography of war, I examine the notion of the staged landscape and the adoption of theatrical language and methodologies by the military. This is a multi-disciplinary perspective informed by a wide range of literature concerning perception, the aerial view, camouflage and the terrain model. It draws on much original material including declassified military documents and archival photographs. The emphasis is on the visualisation of landscape and the scenographic strategies used to create, visualise and rehearse narratives of disguise and exposure. Landscape representation was constructed through the study of aerial photographs and imaginative projection. The perceptual shifts in scale and stereoscopic effects created new optical and spatial ‘truths’. Central to this analysis is the place of the model as strategic spectacle, as stage for rehearsal and re-enactment through performance and play. This research forms the context for an exploration of the extension and translation of similar scenographic strategies in contemporary visual art practice. Five case studies demonstrate how the artist as scenographer is representing the political and cultural landscape.

And the Contents (the summaries are Greer’s own):

Chapter 1: Scenographic strategies

Theatre of War/Strategic Fantasy/Staging the Landscape

This chapter identifies the scenographic strategies that produce the performance landscape for the rehearsal and re-enactment of the Theatre of War. The aim is to define what is meant by strategic scenography and to establish the basic theoretical foundations upon which to build my argument.

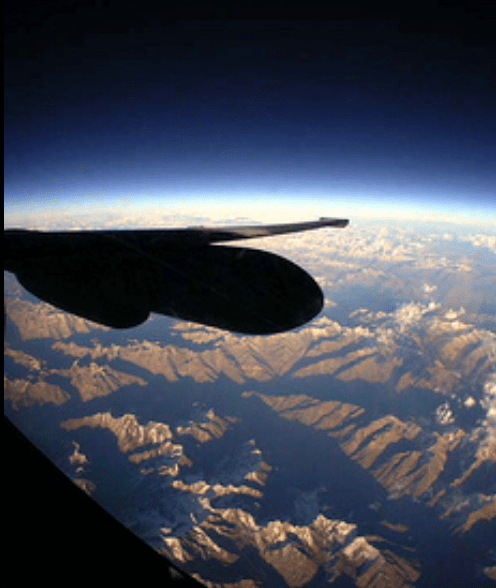

Chapter 2: The Aerial Perspective

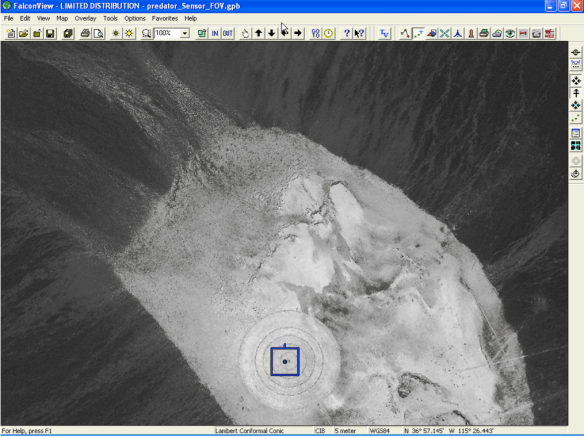

Aerial Theatre/The Stereoscopic View

This chapter focuses on the aerial view and the methodology of the stereoscope. This analysis of the relationship between scenography and topography from an aerial perspective expands on theories of aerial perception and stereoscopy. Drawing on the experiences of the reconnaissance pilots and photo interpreters during wartime, it attempts to understand the scopic conditions under which they visualised the landscape.

Chapter 3: Strategies of Perception

Camouflage Strategies/Fake Nature/The Scenic Effects

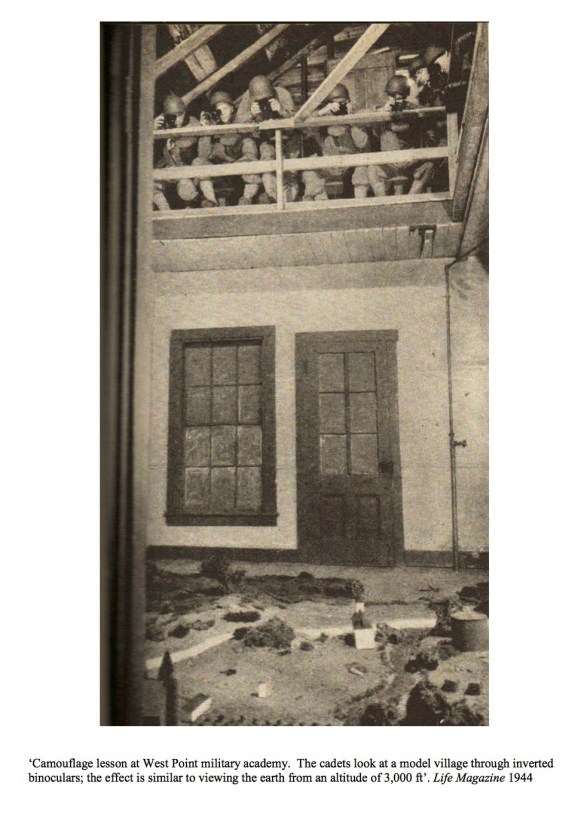

This is a key chapter which looks at the work of Kurt Lewin’s important contribution to an understanding of the perception of landscape. The second section deals specifically with the camouflage strategies adopted by the camoufleurs when staging their illusions in the First and Second World Wars. It provides a historical overview of the main camouflage strategies and then focus on particular scenic elements, e.g. scenery, lighting, props, sound, costume.

Chapter 4: The Territory of the Model

Maps, Models and Games/ The Model as Spectacle/The Terrain Model

This chapter begins with an examination of the methodologies of the map, model and games; the role of mimesis and performativity and the representation of the terrain. What follows is a consideration of the model as a strategic spectacle and its use to represent political ideologies, commercial and military interests and utopian visions. Within an historical context, it examines how the application of new technologies and scopic regimes has expanded the scenographic possibilities of the terrain model.

Chapter 5: Artists’ Manoeuvres

Wafa Hourani and Michael Ashkin − Nomos/Gerry Judah − The Crusader/Mariele Neudecker – Seduction Chaff/Katrin Sigurdardottir – Mappings/Hans Op de Beeck – St Nazaire

This chapter is an exploration of the deployment of scenographic strategies in contemporary artistic practice. Through five case studies it examines how the artist as scenographer has adopted theatrical practices and the methodologies of the model, camera and film as means of representing the political and cultural landscape.

Greer is currently a lecturer in Scenography at Royal Holloway, University of London and in BA and MA Spatial Design at Buckinghamshire New University. You can download her thesis here – it’s a feast of delights, with marvellous illustrations and a perceptive text.

As you can see, Greer’s work focuses on the visual, and I’m equally interested in the role of the other senses in apprehending and navigating the battlefield – hence my continuing interest in corpography (see here and here). So I was also pleased to find a newly translated discussion of the soundscape of the Western Front: Axel Volmar, ‘”In storms of steel”: the soundscape of World War I’, in Daniel Marat (ed), Sounds of modern history: auditory cultures in 19th and 20th century Europe (Oxford: Berghahn, 2014) pp. 227-255; a surprising amount of the text can be accessed via Google Books, but you can also download the draft version via academia.edu. More on Axel’s work (and other downloads, in both German and English) here.

As you can see, Greer’s work focuses on the visual, and I’m equally interested in the role of the other senses in apprehending and navigating the battlefield – hence my continuing interest in corpography (see here and here). So I was also pleased to find a newly translated discussion of the soundscape of the Western Front: Axel Volmar, ‘”In storms of steel”: the soundscape of World War I’, in Daniel Marat (ed), Sounds of modern history: auditory cultures in 19th and 20th century Europe (Oxford: Berghahn, 2014) pp. 227-255; a surprising amount of the text can be accessed via Google Books, but you can also download the draft version via academia.edu. More on Axel’s work (and other downloads, in both German and English) here.

And this too takes us back to Lewin:

‘…new arrivals to the front had not only had to leave behind their home and daily life, but also the practices of perception and orientation to which they were accustomed. With entry into the danger zone of battle, the auditory perception of peacetime yields to a, in many respects, radicalized psychological experience—a shift that the Gestalt psychologist, Kurt Lewin, attempted to articulate with the term “warscape”: for the psychological subject, objects lost most of their peacetime characteristics during wartime because they were henceforth evaluated from a perspective of extreme pragmatism and exclusively in terms of their fitness for war….

‘In place of day-to-day auditory perception, which tended to be passive and unconscious, active listening techniques came to the fore: practices of sound analysis, which might be described as an “auscultation” of the acoustic warscape—the method physicians use to listen to their patients by the help of a stethoscope. In these processes, the question was no longer how the noises as such were structured (i.e. what they sounded like), but rather what they meant, and what consequences they would bring with them for the listeners in the trenches. The training of the ear was based on radically increased attentiveness.

The subject thrust to the front thus comprised the focal point of an auditory space in which locating and diagnostic listening practices became vital to survival.’

For more on sound analysis, see my discussion of sound-ranging on the Western Front here, and the discussion in ‘Gabriel’s Map’ (DOWNLOADS tab).