I’m just back from Beirut, and trying to catch up. Every day I went for a walk along the Corniche, and on the second morning a young Syrian boy asked if he could clean my shoes. I was wearing trainers, but told him that I’d pay him anyway and he could clean my shoes next time I came out; he refused to take the money until I had agreed where and when I would present myself for the service. Heart-warming and hear-breaking, and I can’t get him out of my mind. So here is a quick up-date on the situation (see also my previous posts here and here).

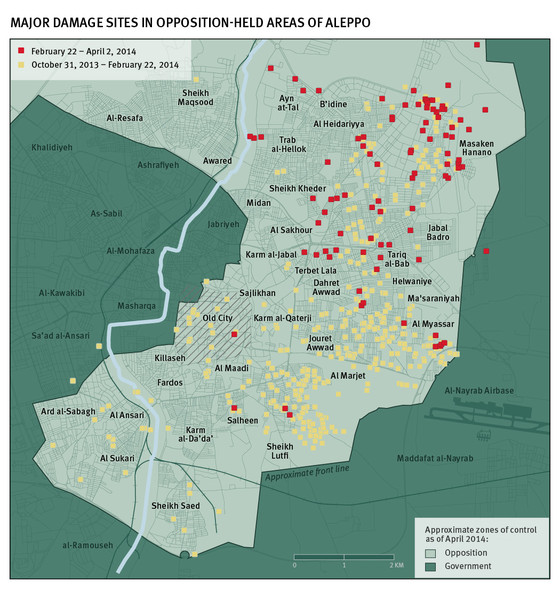

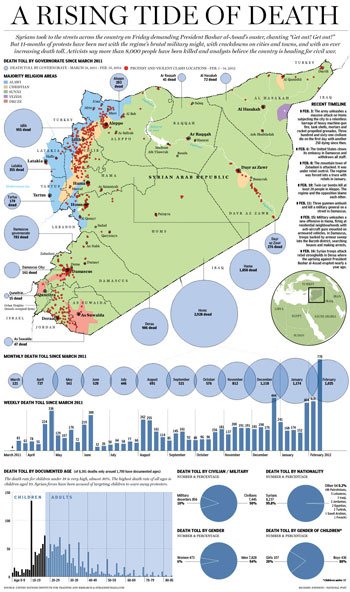

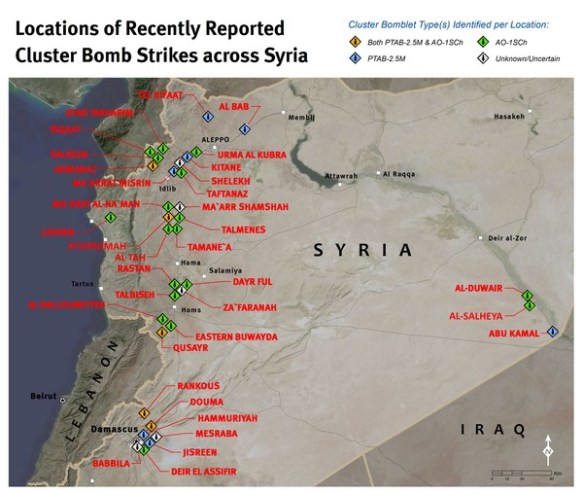

First, this week Foreign Policy published this sobering animated map of casualties from the civil war in Syria based on data from the Human Rights Data Analysis Group:

It visualizes the approximately 74,000 people who died from March 2011 to November 2013. Every flare represents the death of one or more people, the most common causes being shooting, shelling, and field execution. The brighter a flare is, the more people died in that specific time and place. The data used are drawn from the Violations Documentation Center (VDC), the documentation arm of the Local Coordination Committees in Syria which has been one of the eight sources on which HRDAG has based its count. In a June 2013 report, HRDAG cited VDC as the most thorough accounting of casualties in Syria, though the dataset has been found to contain some inconsistencies…

What the map demonstrates is the escalation of the conflict — with data from March 2011 through the VDC’s Nov. 21, 2013 report — and its quick descent from being a smattering of violence to a multi-front war with militias challenging the military (and other militias) almost everywhere at once. What it can’t show, of course, is the horror and destruction of this war.

My image is just a screen grab, of course, so you need to visit the original to see the overall, devastating effect.

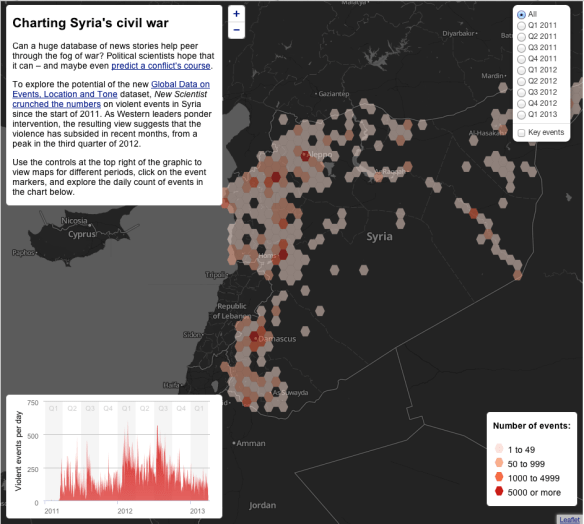

For more detail, I recommend Syria Deeply, a new digital platform that attempts to combine citizen journalism with professional analysis; there’s a profile of the project at start-up over at Fast Company here and a more recent commentary from its founder Lara Setrakian here. I think there are lessons to be learned here about the way publics can be created and brought to engage with conflicts, and that goes for academics as well as journalists.

Second, it’s much harder to find information about those who have been wounded in the conflict – one of my present preoccupations: see here and here – but while I was in Beirut Lebanon’s Daily Star published an interesting report on NGOs working in the borderlands to treat casualties from the war zone. In the Bekaa Valley the International Committee of the Red Cross has treated over 700 people since 2012, while a 20-bed clinic run by Lebanon’s Ighatheyya has treated 135 people since it opened five months ago in Kamed al-Loz. The casualties include pro- and anti-Assad fighters (according to the ICRC, ‘When we know the patients are from opposing sides we separate them by placing them on different floors … We make sure they don’t know the other is there’) and civilians alike. Many of them are suffering from infected wounds because they were initially treated in makeshift facilities in tents or private houses, which is why the perilous journey across the border is so vitally important. Neither the ICRC nor Ighatheyya make cross-border runs. The Star‘s reporters explain:

Many patients are lawfully retrieved from the border by the Lebanese Red Cross, who then take them to a number of cooperating hospitals across the Bekaa Valley for treatment. According to a well-informed source, the ICRC has contracted four hospitals, in Chtaura, Jib Jenin, Baalbek and Hermel, to care for war wounded Syrians.

After surgery patients are often referred to clinics run by other non-governmental organizations, such as Ighatheyya, who oversee the patients’ convalescence…. Ighatheyya is [also] in the process of building a fully equipped 30-bed hospital in the border town of Arsal, where many refugees and combatants cross into Lebanon.

Another major locus of emergency medical treatment is Tripoli, just 30 km from the border and the primary treatment centre for Syrians seeking emergency medical assistance in northern Lebanon. Médecins Sans Frontières, which also operates from four locations in the Bekaa Valley, has been supporting local clinics and hospitals here since February 2012 (and it’s been working inside Syria since March 2011).

NGOs are not the only organisations on the field. Last summer NBC described the operation of a new clinic set up by the Syrian National Opposition to treat opposition fighters. It too is in the Bekaa Valley, which is for the most part controlled by Hezbollah – which is of course militantly pro-Asad. Four days after the clinic opened a local militia aligned with Hezbollah broke into the compound and forced a rapid evacuation, and early last summer armed men attacked an ambulance transporting a patient to surgery and kidnapped him: ‘Since then, the Lebanese Red Cross has refused to transport the clinic’s patients in ambulances through certain Hezbollah-dominated areas without an army escort. And private cars carrying patients through those areas have been shot at.’

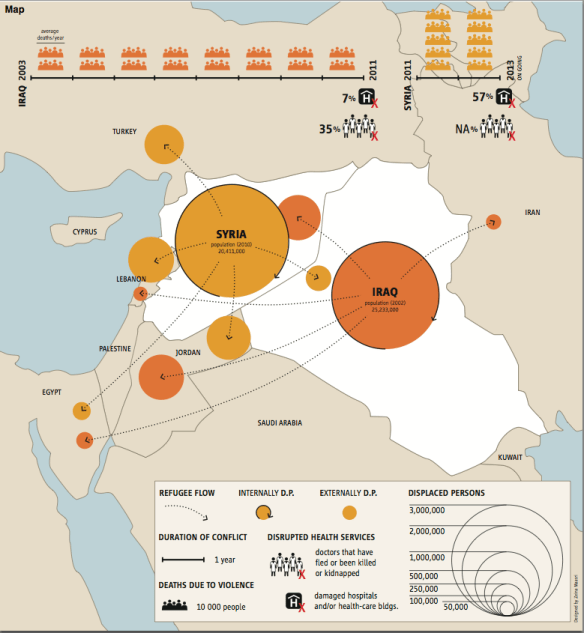

For more on the transnational ‘therapeutic geographies’ involved in the wars in Iraq and Syria, see Omar Dewachi, Mac Skelton, Vinh-Kim Nguyen, Fouad Fouad, Ghassan Abu Sitta, Zeina Maasri and Rita Giacaman, ‘The Changing Therapeutic Geographies of the Iraqi and Syrian Wars’, forthcoming in The Lancet. And for a discussion of the regional geopolitics of all this, including a corrective to the claim that the war in Syria is simply ‘spilling over’ into Lebanon, see Bélen Fernández over at warscapes here.

As MSF emphasises, refugees from the conflict in Syria need more than emergency treatment for war wounds: ‘The epidemiological profile of populations does not change when they cross borders; those who needed medications for chronic conditions in Syria still need them in Lebanon.’ And, clearly, they have other pressing needs too:

As MSF emphasises, refugees from the conflict in Syria need more than emergency treatment for war wounds: ‘The epidemiological profile of populations does not change when they cross borders; those who needed medications for chronic conditions in Syria still need them in Lebanon.’ And, clearly, they have other pressing needs too:

‘[T]the gaps in service that existed [in June 2012] have not been sufficiently addressed but have in fact widened as more people have streamed across the border. Living conditions among the majority of refugees and Lebanese returnees remain extremely precarious, particularly with winter arriving. More than 50% of those interviewed, whether they were officially registered or not, are housed in substandard structures — inadequate collective shelters, farms, garages, unfinished buildings and old schools — that provide paltry, if any, protection against the elements. The rest are renting houses, but many of those people, now separated from their lives and livelihoods, are struggling to pay the rent. The medical picture has deteriorated as well. More than half of all interviewees (52%) cannot afford treatment for chronic disease care, and nearly one-third of them have had to suspend treatment already underway because it was too expensive to continue. For those who are and are not registered alike, the costs attached to essential primary health care, ante-natal care and institutional deliveries are prohibitive. Among non-registered returnees and internally displaced Lebanese, 63% received no assistance whatsoever from any NGO.’

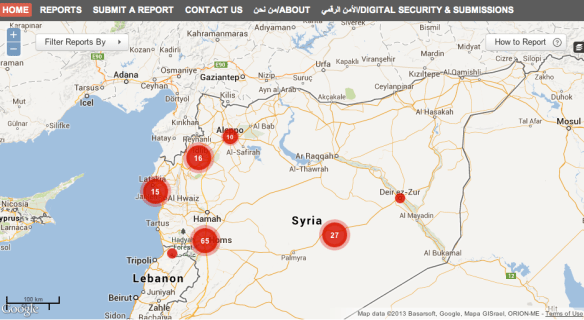

Here’s a recent map of Syrian refugee flows:

For more detail, UNHCR’s tabulations of Syrian refugees in Lebanon can be found here, and there’s a remarkable interactive map here (again, the image below is just a screen grab).

The number of registered refugees in Lebanon – and, as that MSF report indicates, registration is itself a deeply problematic process and the numbers understate the gravity of the situation – is now around one million; Lebanon’s population is four million, so one person in five is a refugee. But wary of its experience with the Palestinian refugee camps – on which Adam Ramadan‘s work is indispensable: his book is due out later this year, but in the meantime see ‘In the ruins of Nahr al-Barid: Understanding the meaning of the camp‘, Journal of Palestine Studies 40 (1) (2010) and ‘Spatialising the refugee camp‘, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 38 (1) (2013) 65-77 – Lebanon has refused to sanction camps for Syrian refugees: hence those ‘tented settlements’ on the map above (and see the image below).

This strategy, or lack of it, is in marked contrast to Jordan, where Al- Za’atari, which opened in July 2012, will soon become the largest refugee camp in the world (below): you can find a sequence of satellite images showing its explosive growth here.

But Lebanon is adamant that it will not sanction any intimations of permanence. Norimitsu Onishi reported recently in the New York Times that

Those fears have forced the refugees to try to squeeze into pre-existing buildings and blend into the landscape. Those with means rent apartments. But hundreds of thousands are living in garages and occupying the nooks and crannies of buildings under construction. Abandoned buildings, including universities and shopping malls, have been taken over in their entirety by refugees.

Here, as usual, there are pickings to be had. Last year Tracy McVeigh reported in the Guardian that

‘While there are widespread reports of extraordinary acts of generosity and kindness by Lebanese towards Syrian refugees, many people here are making money from Syria’s war. Landlords are getting rents for barely habitable properties, stables and outhouses. There are hefty profits to be made in the gun-running business, and refugees are easily exploited as cheap labour. The government is getting military resources from America and Europe, which are keen to see it able to protect its borders. But many others are losing out – those who are trying to house and feed large families along with their own.’

And that includes young boys looking for shoes to clean on the waterfront in Beirut. If you want to donate more than the cost of a shoe-clean, you can reach Oxfam here, the International Rescue Committee here and UNHCR here.