I’m just back from a wonderful time at UC Davis, where I was speaking at a symposium called “Eyes in the skies: drones and the politics of distance warfare.” It was a creative program, packed with insights from Caren Kaplan and Andrea Miller, Priya Satia and Joe Delappe.

On my way back to Vancouver on Wednesday I received an invitation from Britain’s Guardian (in fact, the Sunday version, the Observer) to write something around that very question using the Gavin Hood film “Eyes in the sky” as a peg.

It’s just been published and you can find it here.

At Davis I’d been giving what I think will be my final presentation of “Angry Eyes” (see here and here), so I was still preoccupied with remote platforms and close air support – not the contradiction it sounds – rather than targeted killing (which is the focus of the film). The published version has, inevitably, been edited, so I’m pasting the full-length version below and added some links that might help. There are still lots of short-cuts and elisions, necessarily so for anything of this length, so I hope readers will forgive the inevitable simplifications.

***

Gavin Hood’s Eye in the Sky is a thrillingly intelligent exploration of the political and ethical questions surrounding drone warfare. It’s been carefully researched and is on the cutting-edge of what is currently possible. But there’s a longer history and a wider geography that casts those issues in a different light. As soon as the Wright Brothers demonstrated the possibility of human flight, others were busy imagining flying machines with nobody on board. In 1910 Raymond Phillips captivated crowds in the London Hippodrome with a remotely controlled airship that floated out over the stalls and, when he pressed a switch, released hundreds of paper birds on the heads of the audience below. When he built the real thing, he promised, the birds would be replaced with bombs. Sitting safely in London he could attack Paris, Berlin – or Manchester (a possibility that understandably prompted questions about navigation).

There has always been something hideously theatrical about bombing, from the Hendon air displays in the 1920s featuring attacks on ‘native villages’ to the Shock and Awe visited on the inhabitants of Baghdad in 2003. The spectacle now includes the marionette movements of Predators and Reapers whose electronic strings are pulled from thousands of miles away. And it was precisely the remoteness of the control that thrilled the crowds in the Hippodrome. But what mattered even more was surely the prospect Phillips made so real: bombing cities and attacking civilians far from any battlefield.

Remoteness’ is in any case an elastic measure. Human beings have been killing other human beings at ever greater distances since the invention of the dart, the spear and the slingshot. Pope Urban II declared the crossbow illegal and Pope Innocent II upheld the ban in 1139 because it transformed the terms of encounter between Christian armies (using it against non-Christians was evidently a different matter). The invention of firearms wrought another transformation in the range of military violence, radicalized by the development of artillery, and airpower another. And yet today, in a world selectively but none the less sensibly shrunken by the very communications technologies that have made the deployment of armed drones possible, the use of these remote platforms seems to turn distance back into a moral absolute.

But if it is wrong to kill someone from 7,500 miles away (the distance from Creech Air Force Base in Nevada to Afghanistan), over what distance is it permissible to kill somebody? For some, the difference is that drone crews are safe in the continental United States – their lives are not on the line – and this has become a constant refrain in the drone debates. In fact, the US Air Force has been concerned about the safety of its aircrews ever since its high losses during the Second World War. After Hiroshima and Nagasaki the Air Force experimented with using remotely controlled B-17 and B-47 aircraft to drop nuclear bombs without exposing aircrews to danger from the blast, and today it lauds its Predators and Reapers for their ability to ‘project power without vulnerability’.

It’s a complicated boast, because these remote platforms are slow, sluggish and easy to shoot down – they won’t be seen over Russian or Chinese skies any time soon. They can only be used in uncontested air space – against people who can’t fight back – and this echoes Britain’s colonial tactic of ‘air policing’ its subject peoples in the Middle East, East Africa and along the North-West Frontier (which, not altogether coincidentally, are the epicentres of todays’ remote operations). There are almost 200 people involved in every combat air patrol – Nick Cullather once described these remote platforms as the most labour intensive weapons system since the Zeppelin – and most of them are indeed out of harm’s way. It’s only a minor qualification to say that Predators and Reapers have a short range, so that they have to be launched by crews close to their targets before being handed off to their home-based operators. This is still remote-control war, mediated by satellite links and fiber-optic cables, but in Afghanistan the launch and recovery and the maintenance crews are exposed to real danger. Even so, Grégoire Chamayou insists that for most of those involved this is hunting not warfare, animated by pursuit not combat [see here, here and here].

Yet it’s important not to use this aperçu to lionize conventional bombing. There is an important sense in which virtually all aerial violence has become remarkably remote. It’s not just that bombing has come to be seen as a dismal alternative to ‘boots on the ground’; advanced militaries pick their fights, avoid symmetrical warfare and prefer enemies whose ability to retaliate is limited, compromised or degraded. When he was Secretary of Defense Robert Gates acknowledged that the US had not lost a pilot in air combat for forty years. ‘The days of jousting with the enemy in the sky, of flirting daily with death in the clouds, are all but over,’ writes the far-from-pacifist Mark Bowden, ‘and have been for some time.’ The US Air Force goes to war ‘virtually unopposed’. In short, the distance between the pilot in the box at Creech and the pilot hurtling through the skies over Afghanistan is less than you might think. ‘Those pilots might as well be in Nevada’, says Tom Engelhardt, ‘since there is no enemy that can touch them.’

This suggests that we need to situate armed drones within the larger matrix of aerial violence. Bombing in the major wars of the twentieth century was always dangerous to those who carried it out, but those who dropped bombs over Hamburg or Cologne in the Second World War or over the rainforests of South Vietnam in the 1960s and 70s were, in a crucial sense, also remote from their targets. Memoirs from Bomber Command crews confirm that the target cities appeared as lights sparkling on black velvet, ‘like a Brocks firework display.’ ‘The good thing about being in an aeroplane at war is that you never touch the enemy’, recalled one veteran. ‘You never see the whites of their eyes. You drop a four-thousand-pound cookie and kill a thousand people but you never see a single one of them.’ He explained: ‘It’s the distance and the blindness that enables you to do these things.’ The crews of B-52 bombers on Arc Light missions dropped their loads on elongated target boxes that were little more than abstract geometries. ‘Sitting in their air-conditioned compartments more than five miles above the jungle’, the New York Times reported in 1972, the crews ‘knew virtually nothing about their targets, and showed no curiosity.’ One of them explained that ‘we’re so far away’ that ‘it’s a highly impersonal war for us.’

Distance no longer confers blindness on those who operate today’s drones. They have a much closer, more detailed view of the people they kill. The US Air Force describes their job as putting ‘warheads on foreheads’, and they are required to remain on station to carry out a battle damage assessment that is often an inventory of body parts. Most drone crews will tell you that they do not feel thousands of miles away from the action: just eighteen inches, the distance from eye to screen.

Their primary function is to provide intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance. This was exactly how the Wright brothers thought military aircraft would be used – in July 1917 Orville insisted that ‘bomb-dropping’ would be at best a minor role and almost certainly useless, though he was speaking before the major air offensives in the final year of the war and could have had no inkling of what was to come in the Second World War. The Predator and its precursors were designed to identify targets for conventional strike aircraft over the Balkans in the 1990s, and thirty years later it is still those ‘eyes in the sky’ that make the difference. Although drones have been armed since 2001, until late 2012 they were directly responsible for only 5-10 per cent of all air strikes in Afghanistan. But they were involved in orchestrating many more. Flying a Predator or a Reaper ‘is more like being a manager’, one pilot explained to Daniel Rothenberg: ‘You’re managing multiple assets and you’re involved with the other platforms using the information coming off of your aircraft.’ In principle it’s not so different from using aircraft to range targets for artillery on the Western Front, but the process has been radicalized by the drone’s real-time full-motion video feeds that enable highly mobile ‘targets of opportunity’ to be identified and tracked. In the absence of ground intelligence, this becomes crucial: until drones were relocated in sufficient numbers from Afghanistan and elsewhere to enable purported IS-targets in Syria to be identified, most US aircraft were returning to base without releasing their weapons.

Armed drones are used to carry out targeted killings, both inside and outside areas of ‘active hostilities’, and to provide close air support to ground troops. Targeted killing has spurred an intense critical debate, and rightly so – this is the focus of Eye in the sky too – but close air support has not been subject to the same scrutiny. In both cases, video feeds are central, but it is a mistake to think that this reduces war to a video game – a jibe that in any case fails to appreciate that today’s video games are often profoundly immersive. In fact, that may be part of the problem. Several studies have shown that civilian casualties are most likely when air strikes are carried out to support troops in contact with an enemy, and even more likely when they are carried out from remote platforms. I suspect that drone crews may compensate for their physical rather than emotional distance by ‘leaning forward’ to do everything they can to protect the troops on the ground. This in turn predisposes them to interpret every action in the vicinity of a ground force as hostile – and civilians as combatants – not least because these are silent movies: the only sound, apart from the clacking of computer keys as they talk in secure chat rooms with those watching the video feeds, comes from radio communications with their own forces.

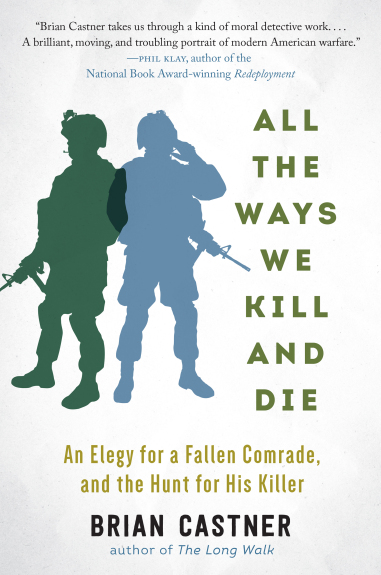

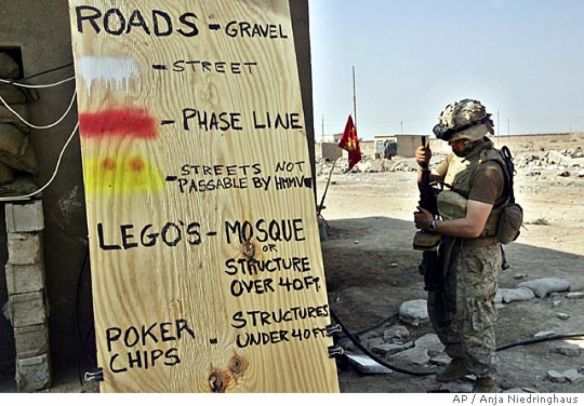

In contrast to those shown in Eye in the Sky, those feeds are often blurry, fuzzy, indistinct, broken, compressed -– and, above all, ambiguous. How can you be sure that is an insurgent burying an IED and not a farmer digging a ditch? The situation is more fraught because the image stream is watched by so many other eyes on the ground, who all have their own ideas about what is being shown and what to do about it. Combining sensor and shooter in the same (remote) platform may have ‘compressed the kill-chain’, as the Air Force puts it, and this is vital in an era of ‘just-in-time’, liquid war where everything happens so fast. Yet in another sense the kill-chain has been spectacularly extended: senior officers, ground force commanders, military lawyers, video analysts all have access to the feeds. There’s a wonderful passage in Brian Castner‘s All the ways we kill and die that captures the dilemma perfectly. ‘A human in the loop?’, Castner’s drone pilot complains.

‘Try two or three or a hundred humans in the loop. Gene was the eye of the needle, and the whole war and a thousand rich generals must pass through him… If they wanted to fly the fucking plane, they could come out and do it themselves.’

This is the networked warfare, scattered over multiple locations around the world, shown in Eye in the Sky. But the network often goes down and gets overloaded – it’s not a smooth and seamlessly functioning machine – and it is shot through with ambiguity, uncertainty and indecision. And often those eyes in the sky multiply rather than disperse the fog of war.