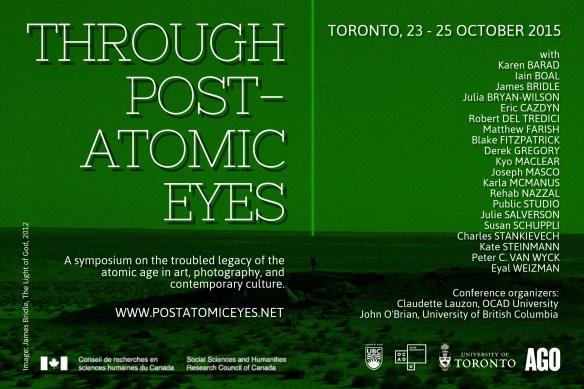

These are very preliminary notes and ideas for my presentation at “Through Post-Atomic Eyes” in Toronto next month: I would really – really – welcome any comments, suggestions or advice. I don’t usually post presentations in advance, and this is still a long way from the finished version, but in this case I am venturing into (irradiated) fields unknown to me until a few months ago…

At first sight, any comparison between America’s nuclear war capability and its drone strikes in Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan, Somalia, Syria and Yemen seems fanciful. The scale of investment, the speed and range of the delivery systems, the nature of the targets, the blast radii and precision of the munitions, and the time and space horizons of the effects are so clearly incommensurable. It’s noticeable that the conversation between Noam Chomsky and Andre Vltchek published as On Western Terrorism: from Hiroshima to drone warfare (2013) says virtually nothing about the two terms in its subtitle.

At first sight, any comparison between America’s nuclear war capability and its drone strikes in Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan, Somalia, Syria and Yemen seems fanciful. The scale of investment, the speed and range of the delivery systems, the nature of the targets, the blast radii and precision of the munitions, and the time and space horizons of the effects are so clearly incommensurable. It’s noticeable that the conversation between Noam Chomsky and Andre Vltchek published as On Western Terrorism: from Hiroshima to drone warfare (2013) says virtually nothing about the two terms in its subtitle.

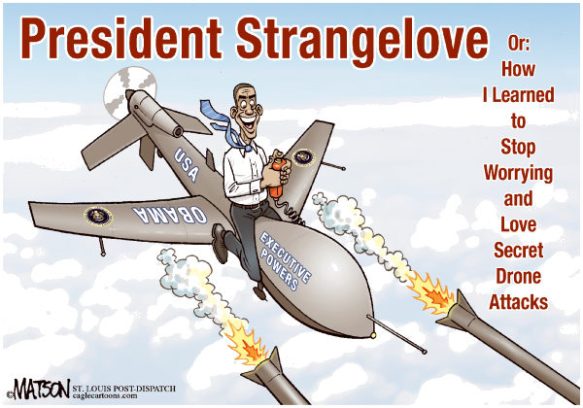

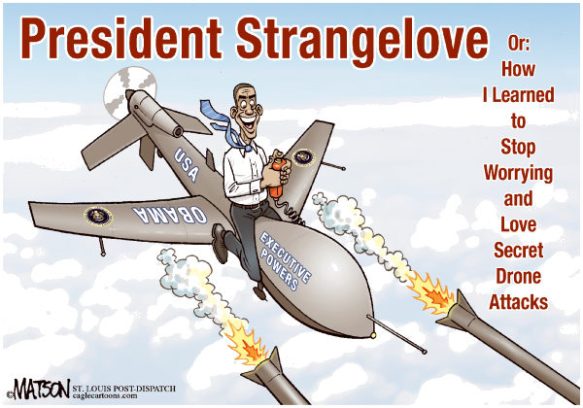

Yet nuclear weapons and drone strikes have both been attended by intense diplomatic, geopolitical and geo-legal manoeuvres, they have both sparked major oppositional campaigns by activist organisations, and they have both had major impacts on popular culture (as the two images below attest).

But there are other coincidences, connections and transformations that also bear close critical examination.

When Paul Tibbets flew the Enola Gay across the blue sky of Hiroshima on 6 August 1945 one of his major concerns was to execute a fast, tight 155 degree turn to escape the effects of the blast from ‘Little Boy’. There is some dispute over the precise escape angle – there’s an exhaustive discussion in the new preface to Paul Nahin‘s Chases and escapes: the mathematics of pursuit and evasion (second edition, 2007) – but the crucial point is the concern for the survival of the aircraft and its crew.

![Enola Gay co-pilot [Robert Lewis]'s sketch after briefing of approach and 155 turn by the B-29s weaponeer William Parsons, 4 August 1945](https://geographicalimaginations.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/enola-gay-co-pilot-robert-lewiss-sketch-after-briefing-of-approach-and-155-turn-by-the-b-29s-weaponeer-william-parsons-4-august-1945.jpg?w=584&h=463)

Tibbets successfully made his escape but four years later, when the US Atomic Energy Commission was developing far more powerful bombs, the Air Force became convinced that escape from those blasts would be impossible. And so it implemented Project Brass Ring which was intended to convert B-47 Stratojet bombers into remotely-piloted aircraft capable of delivering atomic bombs without any loss of American lives. (What follows is taken from Delmer Trester, ‘Thermonuclear weapon delivery by unmanned B-47: Project Brass Ring‘; it was included in A history of the Air Force Atomic Energy Program, 1949-1953, which can be downloaded here; you can obtain a quick overview here).

‘It appeared that the Air Force would need some method to deliver a 10,000-pound package over a distance of 4,000 nautical miles with an accuracy of at least two miles from the center of the target. It was expected the package would produce a lethal area so great that, were it released in a normal manner, the carrier would not survive the explosion effects. Although not mentioned by name, the “package” was a thermonuclear device – the hydrogen or H-bomb…

‘The ultimate objective was to fashion a B-47 carrier with completely automatic operation from take-off to bomb drop… The immediate plan included the director B-47A aircraft as a vital part of the mission. Under direction from the mother aircraft, the missile would take off, climb to altitude and establish cruise speed conditions. While still in friendly territory, the crew aboard the director checked out the missile and committed its instruments to automatically accomplish the remainder of the mission. This was all that was required of the director. The missile, once committed, had no provision for returning to its base… either the B-47 became a true missile and dived toward the target … or a mechanism triggered the bomb free, as in a normal bombing run.’

This was a re-run of Operation Aphrodite, a failed series of experiments carried out in the closing stages of the Second World War in Europe, and – as the images below show – after the war the Air Force had continued to experiment with B-17 aircraft remotely piloted from both ‘director aircraft’ [top image; the director aircraft is top right] and ‘ground control units’ [bottom image]. These operated under the aegis of the Air Force’s Pilotless Aircraft Branch which was created in 1946 in an attempt to establish the service’s proprietary rights over missile development.

But the Brass Ring team soon discovered that their original task had swelled far beyond its original, taxing specifications: in October 1951 they were told that ‘the super-bomb’ would weigh 50,000 lbs. They modified their plans (and planes) accordingly, and after a series of setbacks the first test flight was successful:

‘The automatic take-off, climb and cruise sequence was initiated remotely from a ground control station. The aircraft azimuth, during take-off, was controlled by an auxiliary control station at the end of the runway. Subsequent maneuvers, descent and landing (including remote release of a drag parachute and application of brakes) were accomplished from the ground control station. The test was generally satisfactory; however, there were several aspects – certain level flight conditions, turn characteristics and the suitability of the aircraft as a “bombing platform” – which required further investigation.’

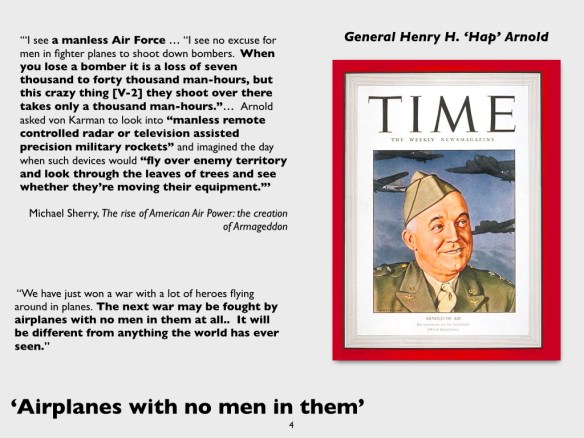

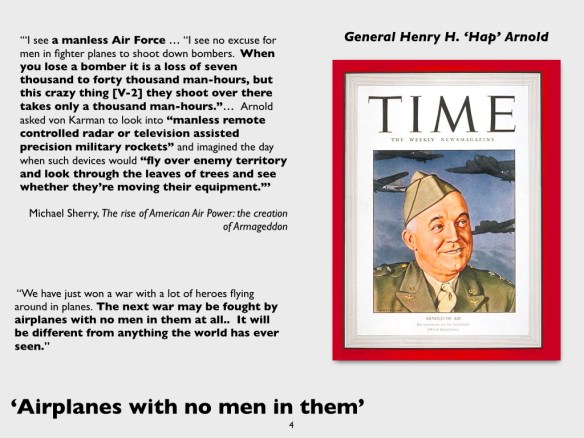

This was part of a larger imaginary in which, as Life had commented in its issue of 20 August 1945, echoing USAAF General Henry H. ‘Hap’ Arnold, ‘robot planes … and atomic bombs will do the work today done by fleets of thousands of piloted bombers.’ (Arnold thought this a mixed blessing, and in an essay ghost-written with William Shockley he noted that nuclear weapons had made destruction ‘too cheap and easy’ – one bomb and one aircraft could replace hundreds of bombs and vast fleets of bombers – and a similar concern is often raised by critics of today’s Predators and Reapers who argue that their remote, often covert operations have lowered the threshold for military violence).

Brass Ring was abandoned on 13 March 1953, once the Air Force determined that a manned aircraft could execute the delivery safely (at least, for those on board). It would be decades before another company closely associated with nuclear research – General Atomics (more here) – supplied the US Air Force with its first MQ-1 Predators.

These were originally conceived as unarmed, tactical not strategic platforms, designed to provide intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance for conventional strike aircraft. But the concern with American lives became a leitmotif of both programs, and one of the foundations for today’s remote operations is the ability (as the USAF has it) to ‘project power without vulnerability’.

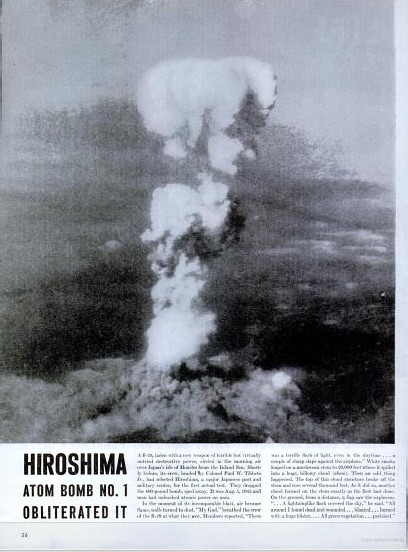

The visible effects of bombing Hiroshima and Nagasaki on the Japanese population were the subject of strict censorship – still photographs were never published, while Japanese media and even US military film crews had their documentary footage embargoed – and public attention in the United States was turned more or less immediately towards visualising ‘Hiroshima USA’ (Paul Boyer is particularly good on this; there are also many images and a good discussion here). Even the US Strategic Bombing Survey indulged in the same speculation: ‘What if the target for the bomb had been an American city?’ it asked in its June 1946 report. ‘The casualty rates at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, applied to the massed inhabitants of Manhattan, Brooklyn, and the Bronx, yield a grim conclusion.’ Although the original targets had been Asian cities it was American cities that were designated as future victims. ‘Physically untouched by the war’ (apart from Pearl Harbor), Boyer wrote,

The visible effects of bombing Hiroshima and Nagasaki on the Japanese population were the subject of strict censorship – still photographs were never published, while Japanese media and even US military film crews had their documentary footage embargoed – and public attention in the United States was turned more or less immediately towards visualising ‘Hiroshima USA’ (Paul Boyer is particularly good on this; there are also many images and a good discussion here). Even the US Strategic Bombing Survey indulged in the same speculation: ‘What if the target for the bomb had been an American city?’ it asked in its June 1946 report. ‘The casualty rates at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, applied to the massed inhabitants of Manhattan, Brooklyn, and the Bronx, yield a grim conclusion.’ Although the original targets had been Asian cities it was American cities that were designated as future victims. ‘Physically untouched by the war’ (apart from Pearl Harbor), Boyer wrote,

‘the United States at the moment of victory perceived itself as naked and vulnerable. Sole possessors and users of a devastating instrument of mass destruction, Americans envisioned themselves not as a potential threat to other peoples, but as potential victims.’

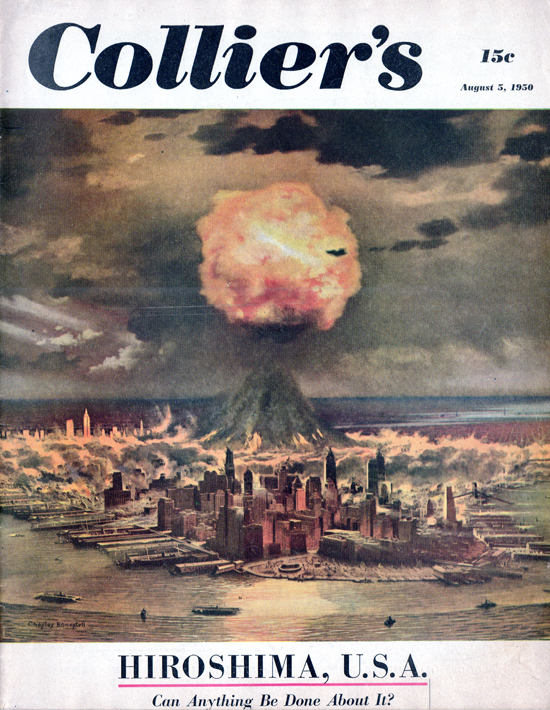

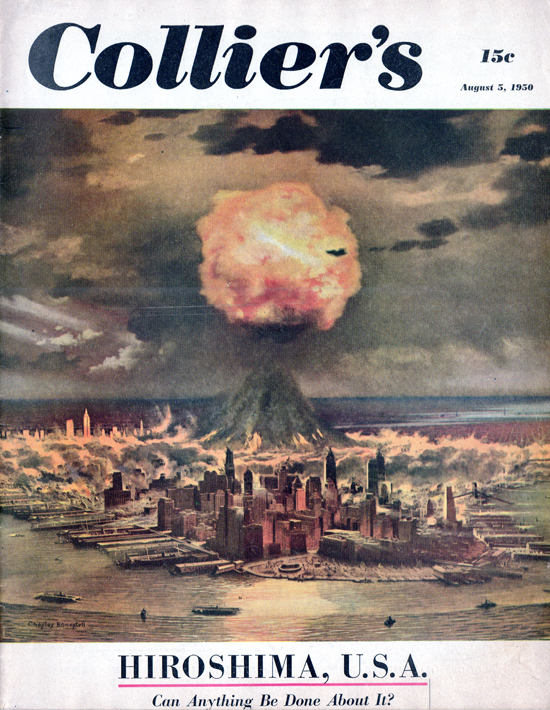

This was the abiding anxiety instilled by the national security state and orchestrated through its military-industrial-media-entertainment complex throughout the post-war decades. Perhaps the most famous sequence of images – imaginative geographies, I suppose –accompanied an essay by John Lear in Collier’s Magazine in August 1950, ‘Hiroshima USA: Can anything be done about it?‘, showing a series of paintings by Chesley Bonestell and Birney Lettick imagining the effects of a nuclear strike on New York:

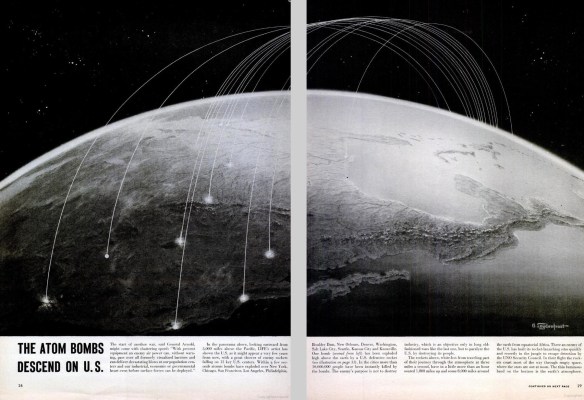

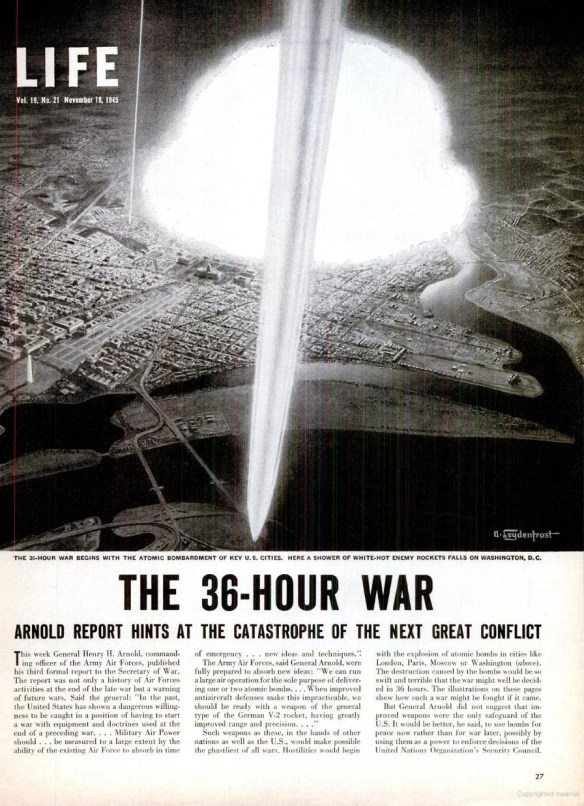

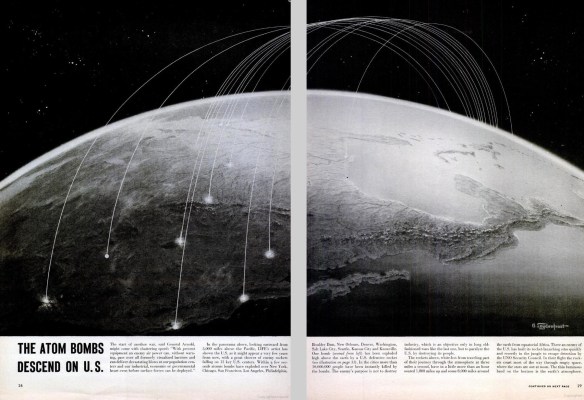

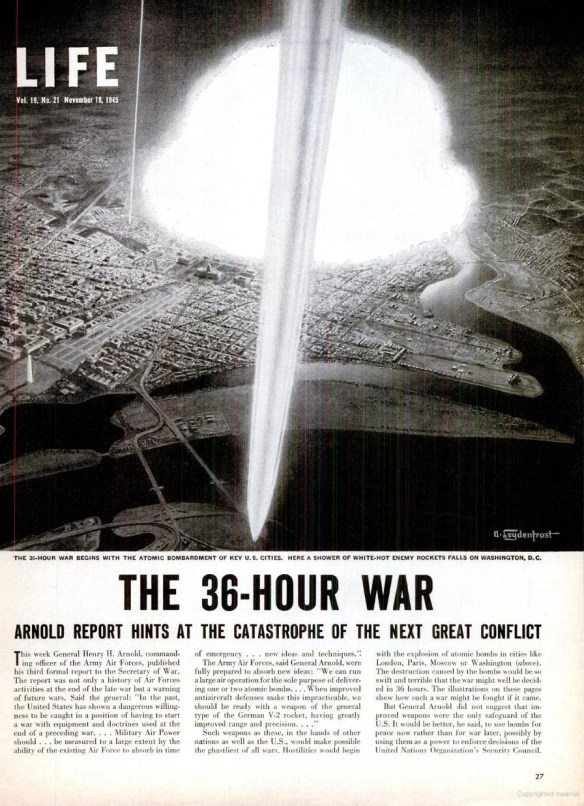

Similar sequences, often accompanied by maps, were produced for many other cities (and the simulations continue: see, for example, here). The images below, from Life on 19 November 1945, come from ‘The 36-Hour War’ (see here for a commentary) that envisaged a nuclear attack on multiple cities across the USA, including Washington DC, from (presumably Soviet) ‘rocket-launching sites [built] quickly and secretly in the jungle’ of equatorial Africa:

As it happened, American cities did indeed become targets – for the US Air Force. According to Eric Schlosser, under General Curtis Le May the goal was

As it happened, American cities did indeed become targets – for the US Air Force. According to Eric Schlosser, under General Curtis Le May the goal was

to build a Strategic Air Command that could strike the Soviet Union with planes based in the United States and deliver every nuclear weapon at once. SAC bomber crews constantly trained and prepared for that all-out assault. They staged mock attacks on every city in the United States with a population larger than twenty-five thousand, practicing to drop atomic bombs on urban targets in the middle of the night. San Francisco was bombed more than six hundred times within a month.

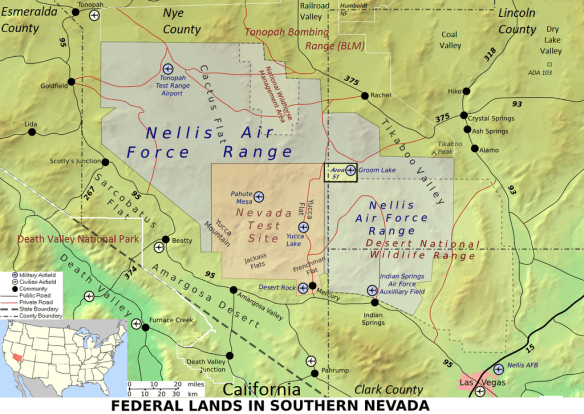

Tests were also conducted at the Nevada Proving Ground, ‘the most nuclear-bombed place on the planet’, to determine the likely effects. One of the purposes of the Strategic Bombing Survey’s Physical Damage Division had been to document the effects of the bombs on buildings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki – to read them as ‘blueprints for the atomic future‘ – and both Japanese and American medical teams had been sent in shortly after the blasts to record their effects on bodies (from 1947 their work was subsumed under the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission). It was now imperative bring the two together and to bring their results home. And so, starting in 1953 with ‘Operation Doorstep’, mannequins were placed inside single-family houses at the Nevada site to calculate the prospects for the survival of what Joseph Masco calls the American ‘nuclearised’ family in the event of a nuclear attack; they subsequently went on public exhibition around the country with the tag line:

Tests were also conducted at the Nevada Proving Ground, ‘the most nuclear-bombed place on the planet’, to determine the likely effects. One of the purposes of the Strategic Bombing Survey’s Physical Damage Division had been to document the effects of the bombs on buildings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki – to read them as ‘blueprints for the atomic future‘ – and both Japanese and American medical teams had been sent in shortly after the blasts to record their effects on bodies (from 1947 their work was subsumed under the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission). It was now imperative bring the two together and to bring their results home. And so, starting in 1953 with ‘Operation Doorstep’, mannequins were placed inside single-family houses at the Nevada site to calculate the prospects for the survival of what Joseph Masco calls the American ‘nuclearised’ family in the event of a nuclear attack; they subsequently went on public exhibition around the country with the tag line:

‘These mannikins could have been real people; in fact, they could have been you.’

In the Second World War experimental bombing runs had been staged against mock German and Japanese targets at the Dugway Proving Ground but – significantly – the buildings had no occupants: as Tom Vanderbilt wryly remarks, now ‘the inhabitants had been rewritten into the picture’ because the objective was to calibrate the lives of Americans.

I have borrowed this image from the mesmerising work of artist Rachele Riley, whose project on The evolution of silence centres on Yucca Flat in the Nevada Test Site and raises a series of sharp questions about both the imagery and the soundscape of the nuclear age.

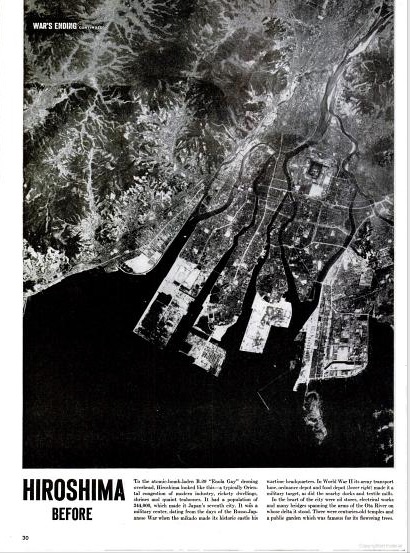

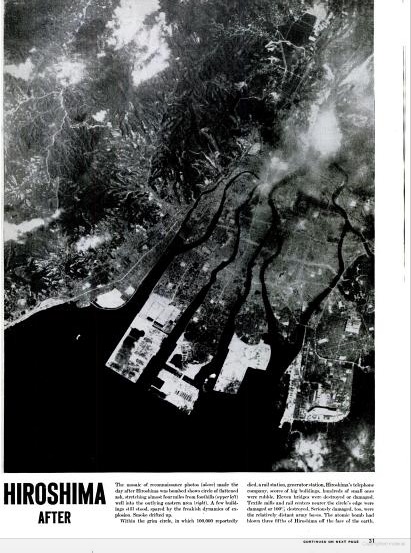

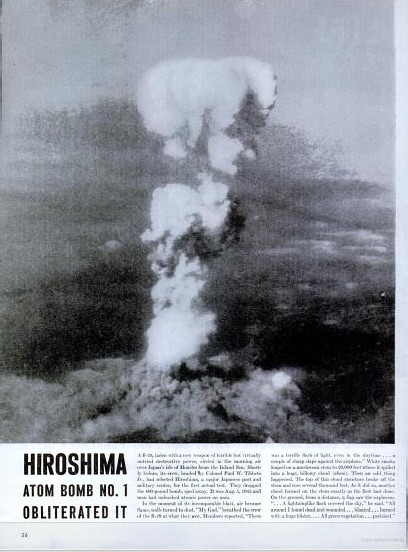

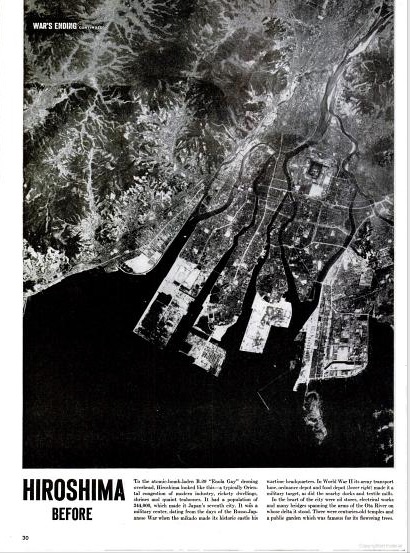

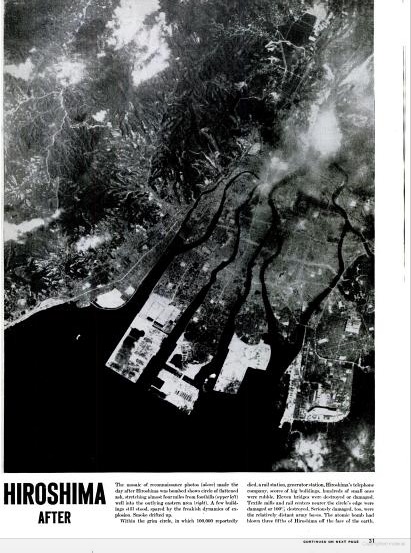

The power of the image – ‘the nuclear sublime’ – was one of the central objectives of the attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki: ‘the weapon’s devastating power had to be seen to be believed,’ as Kyo Maclear observed, and it had to be seen and believed in Moscow as well as in Tokyo. Here the visual economies of nuclear attacks are radically different from drone strikes. In the immediate aftermath there was no shortage of atomic ‘views from the air’ – aerial photographs of the vast cloud towering into the sky and of Hiroshima before and after the bomb. Here is Life (sic) on 20 August 1945:

Yet for the most part, and with some significant exceptions, aerial views are singularly absent from today’s drone wars. To Svea Braeunert (‘Bringing the war home: how visual artists return the drone’s gaze‘) that is all the more remarkable because drone strikes are activated by what video artist Harun Farocki called operative images: but that is also the reason for the difference. Aerial photographs of Hiroshima or Nagasaki reveal a field of destruction in which bodies are conspicuously absent; the resolution level is too coarse to discern the bomb’s victims.

But the video feeds from a Predator or Reaper, for all their imperfections, are designed to identify (and kill) individuals, and their aerial gaze would – if disclosed – reveal the bodies of their victims. That is precisely why the videos are rarely released (and, according to Eyal Weizman, why satellite imagery used by investigators to reconstruct drone strikes is degraded to a resolution level incapable of registering a human body – which remains ‘hidden in the pixels‘ – and why their forensic visual analysis is forced to focus on buildings not bodies).

One might expect visual artists to fill in the blank. Yet – a further contrast with Hiroshima – apart from projects like Omar Fast’s ‘5,000 Feet is Best’ (above) and Thomas van Houtryve’s ‘Blue Sky Days’ (below) there have been precious few attempts to imagine drone strikes on American soil.

Perhaps this is because they are so unlikely: at present these remote platforms can only be used in uncontested air space, against people or states who are unable (or in the case of Pakistan, unwilling) to defend themselves. But there has been a protracted debate about such strikes on American citizens (notably the case of Anwar al-Awlaki) and a concerted attempt to focus on the rules followed by the CIA and JSOC in their programs of targeted killing (which has artfully diverted public attention to Washington and away from Waziristan).

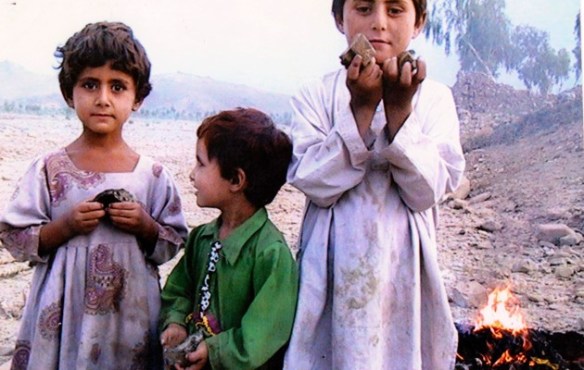

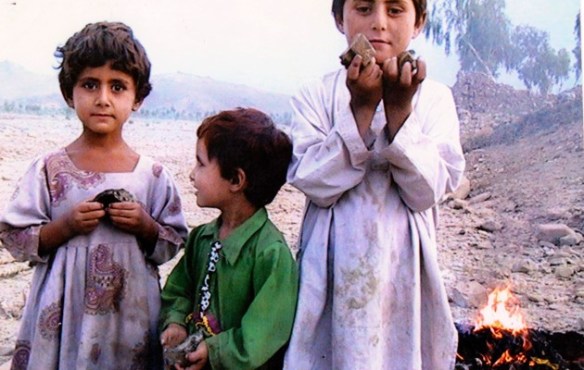

There is also a visceral, visible continuity between the two: just as in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, there has been little public concern over the victims of drone strikes, the vast majority of whom have once again been Asian.

If the targeting process continues to be racialised, it also continues to be bureaucratised. After the Second World War the US Air Force was determined to speed up its targeting cycle, and in 1946 started to compile a computerised database of potential targets in the Soviet Union; this was soon extended to Soviet satellites and Korea, and by 1960 the Bombing Encyclopedia of the World (now called the ‘Basic Encyclopedia’) contained 80,000 Consolidated Target Intelligence Files. These were harvested to plan Strategic Air Command’s nuclear strikes and to calibrate Damage and Contamination Models. One of the analysts responsible for nominating targets later described the process as ‘the bureaucratisation of homicide’. Similar criticisms have been launched against the ‘disposition matrix’ used by the CIA to nominate individuals authorised for targeted killing (see here and here); most of these are in Pakistan, Somalia, and Yemen, though there are other kill lists, including Joint Prioritised Effects Lists compiled by the US military for war zones in Afghanistan and Iraq. In both cases the target files are in principle global in reach, and both nuclear strikes and targeted killings (outside established war zones) are judged to be sufficiently serious and ‘sensitive’ to require direct Presidential approval.

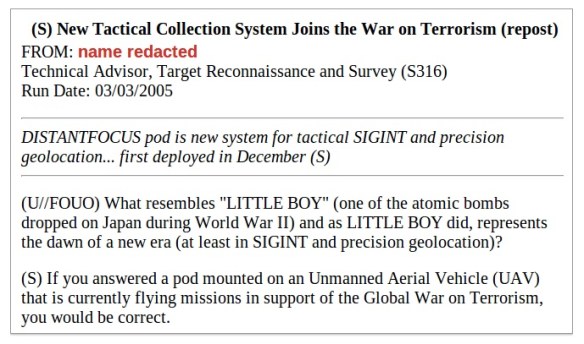

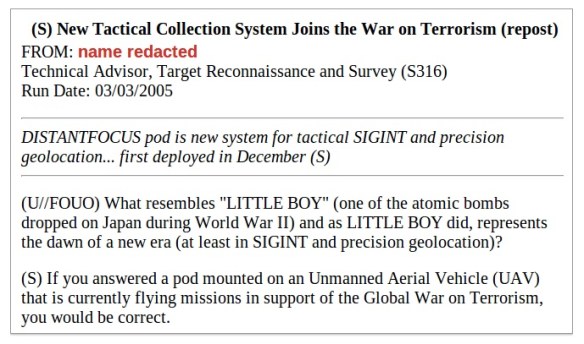

Speeding up the targeting cycle has involved more than the pre-emptive identification of targets. In contrast to the fixed targets for nuclear strikes, today’s Predators and Reapers are typically directed against mobile targets virtually impossible to locate in advance. Pursuing these fleeting ‘targets of opportunity’ relies on a rapidly changing and expanding suite of sensors to identify and track individuals in near-real time. In 2004 the Defense Science Board recommended the Pentagon establish ‘a “Manhattan Project”-like program for ID/TTI’ [identification, tagging, tracking and locating], and one year later a Technical Advisor working for the National Security Agency’s Target Reconnaissance and Survey Division posed the following question:

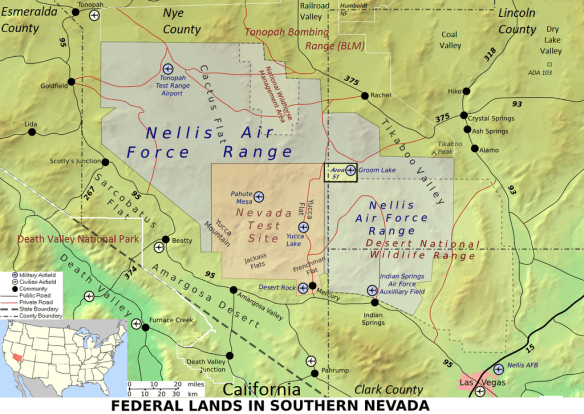

The onboard sensor suite in the pod has since become ever more effective in intercepting and monitoring electronic communications as part of a vast system of digital data capture, but Predators had already been armed with Hellfire missiles to compress the kill-chain still further, and to many commentators the most radical innovation in later modern war has been the fusion of sensor and shooter in a single platform. The new integrated systems were first trialled – on a Predator flown by test pilots from General Atomics – in February 2000 at Indian Springs Auxiliary Field. The main objective was to hunt and kill Osama bin Laden, and at the request of the Air Force and the CIA a series of tests was carried out.

First, the Air Force wanted to determine whether the Predator could withstand a missile being fired from beneath its insubstantial wings (a ghostly echo of earlier anxieties over the survivability of the Enola Gay and its successors – though plainly much reduced by the absence of any pilot on board).

Second, the CIA wanted to assess the likely effects of a Hellfire strike on the occupants of a single-storey building like those found in rural Afghanistan (nuclear tests had used mannequins and pigs as human surrogates; these used plywood cut-outs and watermelons).

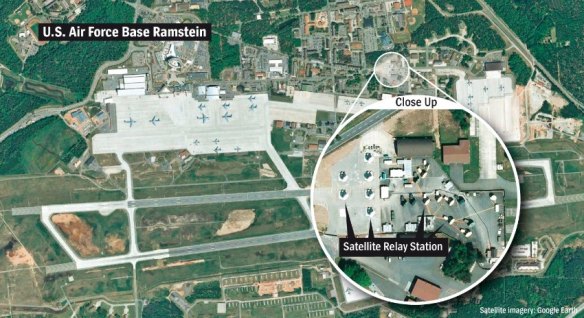

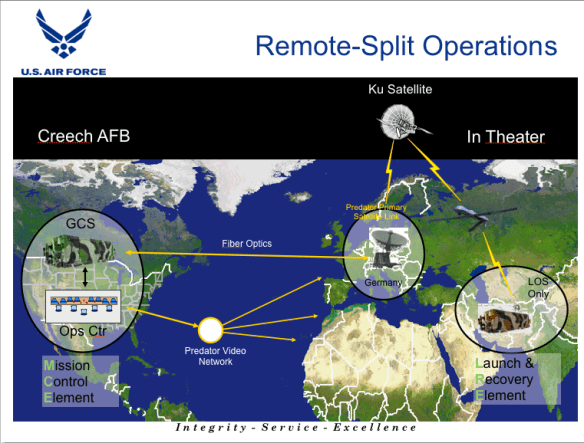

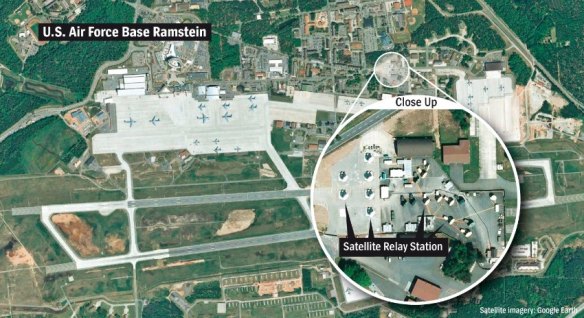

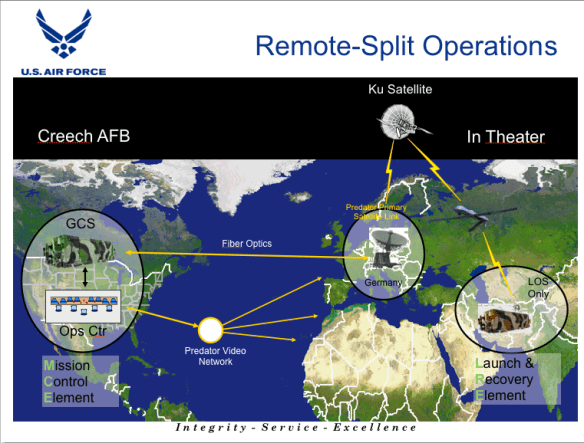

Both sets of tests were eventually successful (see also here) but, as Richard Whittle shows in consummate detail, a series of legal and diplomatic obstacles remained. In order to secure satellite access over Afghanistan, previous Predator flights to find bin Laden had been flown from a ground control station at Ramstein Air Base in Germany. But using a Predator to kill bin Laden was less straightforward. After protracted debate, US Government lawyers agreed that a Predator armed with a missile would not violate the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, which eliminated nuclear and conventional missiles with intermediate ranges but which – unhelpfully for the CIA – defined missiles as ‘unmanned, self-propelled … weapon-delivery vehicles’; the lawyers determined that the Predator was merely a platform and, unlike a cruise missile, had no warhead so that it remained outside the Treaty. But they also insisted that the Status of Forces Agreement with Germany would require Berlin’s consent for the activation of an armed Predator. (The United States stored tactical nuclear warheads at Ramstein until 2005; although the US insisted it retained control over them, in the event of war they were to have been delivered by the Luftwaffe as part of a concerted NATO nuclear strike).

Both sets of tests were eventually successful (see also here) but, as Richard Whittle shows in consummate detail, a series of legal and diplomatic obstacles remained. In order to secure satellite access over Afghanistan, previous Predator flights to find bin Laden had been flown from a ground control station at Ramstein Air Base in Germany. But using a Predator to kill bin Laden was less straightforward. After protracted debate, US Government lawyers agreed that a Predator armed with a missile would not violate the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, which eliminated nuclear and conventional missiles with intermediate ranges but which – unhelpfully for the CIA – defined missiles as ‘unmanned, self-propelled … weapon-delivery vehicles’; the lawyers determined that the Predator was merely a platform and, unlike a cruise missile, had no warhead so that it remained outside the Treaty. But they also insisted that the Status of Forces Agreement with Germany would require Berlin’s consent for the activation of an armed Predator. (The United States stored tactical nuclear warheads at Ramstein until 2005; although the US insisted it retained control over them, in the event of war they were to have been delivered by the Luftwaffe as part of a concerted NATO nuclear strike).

The need to bring Berlin onside (and so potentially compromise the secrecy of the project) was one of the main reasons why the ground control station was relocated to Indian Springs, connected to the satellite link at Ramstein through a fibre-optic cable under the Atlantic:

In fact, since 1952 Indian Springs had been a key portal into the Nevada Test Site – its purpose was to support both US Atomic Energy Commission nuclear testing at the Nevada Proving Grounds and US Air Force operations at the Nellis Air Force Base’s vast Gunnery and Bombing Range – and in June 2005 it morphed into Creech Air Force Base: the main centre from which ‘remote-split’ operations in Afghanistan, Pakistan and elsewhere are flown by USAF pilots. Most of the covert operations are directed by the CIA (some by Joint Special Operations Command), but the Predators and Reapers are used for more than targeted killing; the primary missions are still to provide ISR for conventional strikes and now also close air support for ground troops.

The geographies overlap, coalesce and – even allowing for the differences in scale – conjure up a radically diffuse and dispersed field of military violence. When Tom Vanderbilt described ‘a war with no clear boundaries, no clear battlefields … a war waged in such secrecy that both records and physical locations are often utterly obscured’ he was talking about nuclear war. But exactly the same could be said of today’s drone wars, those versions of later modern war in which the body becomes the battle space (‘warheads on foreheads’) and the hunting ground planetary: another dismal iteration of the ‘everywhere war’ (see here and here).

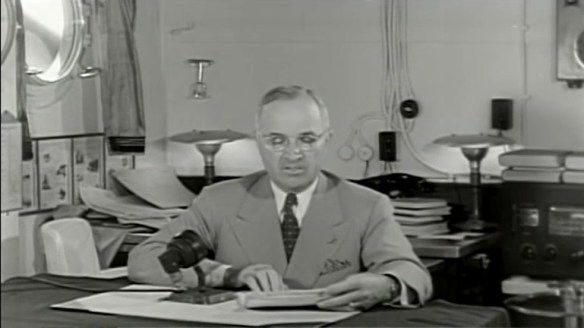

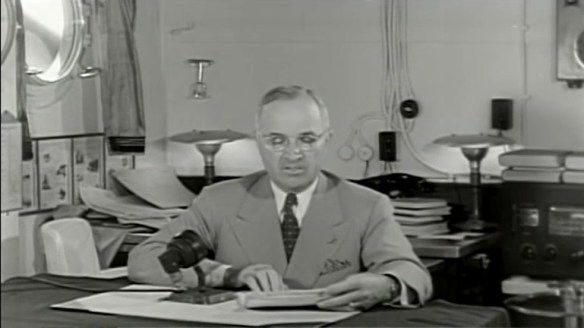

For all these connections and intersections, a key divide is the issue of civilians and casualties. On 9 August 1945 President Truman (below) described Hiroshima as a ‘military base’ selected ‘because we wished in this first attack to avoid, insofar as possible, the killing of civilians’.

This was simply untrue, and similar – often no less deceptive – formulations are routinely used to justify US drone strikes and to minimise what is now called ‘collateral damage’. Still, the scale of civilian casualties is clearly different: usually dozens rather than hundreds of thousands.

And yet, there is something irredeemably personal and solitary about the response to death from either cause; parents searching for the bodies of their children in the ruins are as alone in Dhatta Khel as they were in Hiroshima. When Yukiko Hayashi [her real name is Sachiko Kawamura] describes the anguish of a young woman and her father finding the remains of their family – the poem, ‘Sky of Hiroshima‘, is autobiographical – it is surely not difficult to transpose its pathos to other children in other places:

Daddy squats down, and digs with his hands

Suddenly, his voice weak with exhaustion, he points

I throw the hoe aside

And dig at the spot with my hands

The tiles have grown warm in the sun

And we dig

With a grim and quiet intent

Oh…

Mommy’s bone

Oh…

When I squeezed it

White powder danced in the wind

Mommy’s bone

When I put it in my mouth

Tasted lonely

The unbearable sorrow

Began to rise in my father and I

Left alone

Screaming, and picking up bones

And putting them into the candy box

Where they made a rustle

My little brother was right beside my mommy

Little more than a skeleton

His insides, not burnt out completely

Lay exposed…

In The Theater of Operations Joseph Masco draws a series of distinctions between the US national security state inaugurated by the first atomic bombs and the counter-terror state whose organs have proliferated since 9/11.

In The Theater of Operations Joseph Masco draws a series of distinctions between the US national security state inaugurated by the first atomic bombs and the counter-terror state whose organs have proliferated since 9/11.

He properly (and brilliantly) insists on the affects instilled in the American public by the counter-terror state as vital parts of its purpose, logic and practice – yet he says virtually nothing about the affects induced amongst the vulnerable populations forced to ‘live under drones’ and its other modes of military and paramilitary violence.

In Waziristan no air raid sirens warn local people of a strike, no anti-aircraft systems protect them, and no air-raid shelters are available for them to seek refuge.

Hence young Zubair Rehman’s (above, top right) heartbreaking admission after a drone killed his grandmother as she tended the fields in Ghundi Kala in North Waziristan (see here and here):

‘I no longer love blue skies. In fact, I now prefer grey skies. The drones do not fly when the skies are grey.’

![Enola Gay co-pilot [Robert Lewis]'s sketch after briefing of approach and 155 turn by the B-29s weaponeer William Parsons, 4 August 1945](https://geographicalimaginations.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/enola-gay-co-pilot-robert-lewiss-sketch-after-briefing-of-approach-and-155-turn-by-the-b-29s-weaponeer-william-parsons-4-august-1945.jpg?w=584&h=463)