Neve Gordon‘s review of Grégoire Chamayou‘s A theory of the drone on Al-Jazeera is now available in a more extended form at Counterpunch here. It’s a succinct summary of the book’s main theses, though there’s not much critical engagement with them (you can access my own series of commentaries here [scroll down]). He closes his review like this:

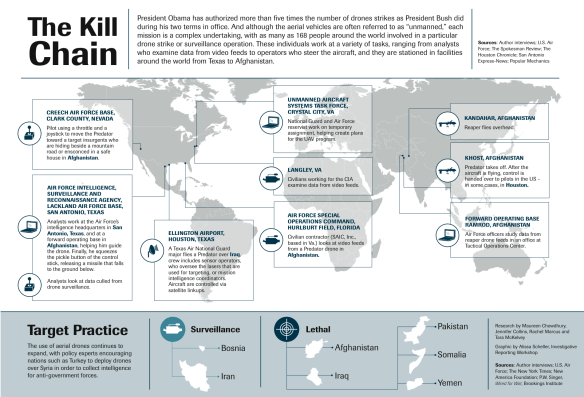

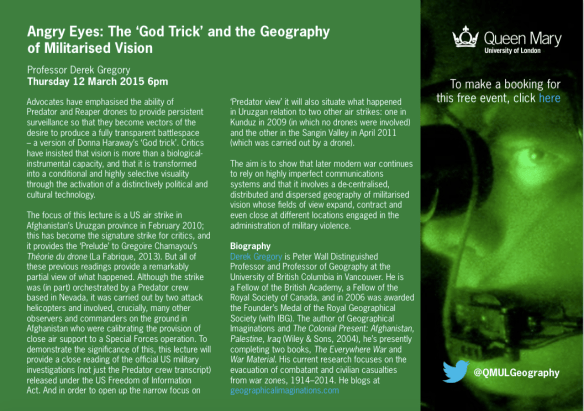

Because drones transform warfare into a ghostly teleguided act orchestrated from a base in Nevada or Missouri, whereby soldiers no longer risk their lives, the critical attitude of citizenry towards war is also profoundly transformed, altering, as it were, the political arena within drone states.

Drones, Chamayou says, are a technological solution for the inability of politicians to mobilize support for war. In the future, politicians might not need to rally citizens because once armies begin deploying only drones and robots there will be no need for the public to even know that a war is being waged. So while, on the one hand, drones help produce the social legitimacy towards warfare through the reduction of risk, on the other hand, they render social legitimacy irrelevant to the political decision making process relating to war. This drastically reduces the threshold for resorting to violence, so much so that violence appears increasingly as a default option for foreign policy. Indeed, the transformation of wars into a risk free enterprise will render them even more ubiquitous than they are today.

Neve is the author of the indispensable Israel’s occupation, and while these paragraphs closely follow A theory of the drone the title of the book is in the singular – and so I’m left wondering about military violence that isn’t orchestrated from Nevada or Missouri and what other ‘theories of the drone’ are needed to accommodate a ‘drone state’ like Israel (not that I’m sure what a ‘drone state’ is…)?

The Israeli military is no stranger to what, following Joseph Pugliese, I’ll call prosthetic violence. While Israel remains a leading manufacturer of drones (see here and here), and routinely deploys them over the occupied territories, it also enforces its ‘Death Zone‘ in Gaza through an automated, ground-based ‘Spot and Strike’ shooting system:

The soldiers, trainees in the course for the “Spot and Strike” system, sit in a tower facing the wilderness of the southern Negev, at the far edge of the Field Intelligence School at the Sayarim base, not far from Ovda. Between their tower and the wide-open desert stands another tower topped by a metal dome. With the press of a button the dome opens to reveal a heavy machine gun. Small tweaks of the joystick aim the barrel. To the right of the gun is a camera, which transmits a clear picture of the target onto a screen opposite the soldier. A press of the button and the figure in the crosshairs is hit by a 0.5-inch bullet.

This dovetails (wrong bird) with a discussion of online shooting in A theory of the drone, but here is risk-transfer war waged over extremely short distances. ‘Remoteness’ is as much an imaginative as a physical condition, and one that is constantly manipulated so that the threat from Hamas’s rockets and tunnels becomes ‘danger close’ even as the hideous consequences of Israel’s own military offensives become distanced (unless, of course, you choose to turn killing into a spectator sport). In Israel, it seems, these prosthetic assemblages – of which drones are a vital part – serve to animate a deeply militarised society in which evidence of a martial stance is precisely a prerequisite for its claims to legitimacy.

So we clearly need a more inclusive analysis of the prosthetics of military violence – the bio-technical means by which its range is extended – that acknowledges the role of drones for more than ‘targeted killing’ and which incorporates other emergent modalities altogether, including cyberwarfare. One of the best places to start thinking through these issues, in relation to drones at any rate, is Joseph’s tour de force, State violence and the execution of law (2013), which emphasises how ‘through a series of instrumental mediations, the biological human actor becomes coextensive with the drone that she or he pilots from the remote ground control station’ (p. 184) (I connected this to Grégoire’s theses here).

The experience may be more conditional than this allows, though. Timothy Cullen‘s study of USAF crews training to operate the MQ-9 Reaper found that the sense of ‘co-extension’ – or bioconvergence – was much stronger among sensor operators than pilots:

After a couple hundred hours of flight experience and a sense of comfort with the modes, interfaces, and capabilities of the sensor ball, sensor operators began to feel like they were a part of the machine. With proficiency as a “sensor,” sensor operators found themselves shifting and straining their bodies in front of the [Heads Up Display] to look around an object. As pilots flew closer to a target, the transported operators tilted their heads in anticipation of the camera’s [redacted]. Feelings of remote presence helped sensor operators move their bodies, and instructors believed that operators who felt as if they were “flying the sensor” could hold their attention longer on a scene…

Both pilots and sensor operators said pilots did not transport themselves conceptually into the machine to the same extent as a sensor operator. Nor did pilots attain similar feelings of connection and control with Reaper as they did with their previous aircraft.

The term ‘prosthetics’ implies these are at once extensions and embodiments of a military violence whose prosthetics also assume more mundane bioconvergent forms. This is an obvious but in most cases strangely overlooked point. Joseph mentions it in passing, juxtaposing his ‘mobilisation of the prosthetic trope’ with ‘the material literality of prosthetics: drones as the militarized prosthetics of empire inherently generate civilian amputees in need of prosthetic limbs’ (p. 214). There’s also a suggestive discussion in Jennifer Fluri‘s ‘States of (in)security’, which devotes a whole section to what she calls ‘prosthetics biopower’ and the multiply corporeal geographies of contemporary wars [Environment and Planning D: Society & Space 32 (2014) 795-814]. Although Jennifer doesn’t directly connect these intimacies to distant vectors of military violence, the implication (and invitation) is clearly there.

So let me try to supplement her observations, drawing in part on my project on military-medical machines that treats (among other theatres of war) the evacuation of injured soldiers and civilians in Afghanistan. It’s important to trace the two pathways, as I’ll show in a moment (and I’ll say much more about this in a later post), but it’s also necessary to remember, as Sarah Jain crisply observes in her classic essay on ‘The prosthetic imagination‘ (p. 36), that ‘it usually is not the same body that is simultaneously extended and wounded’ [Science, technology and human values 24 (1) (1999) 31-54]. That said, there is a distinctively corporeal geography to those that are.

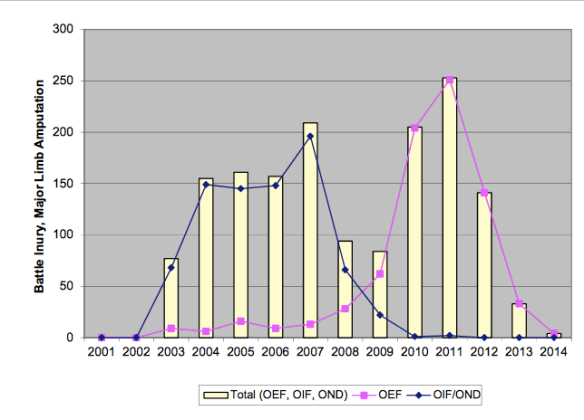

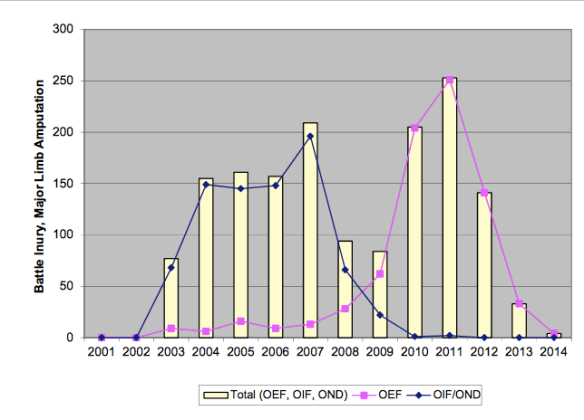

The incidence of devastating injuries to the limbs of troops in Iraq and Afghanistan (see the graph above; for comparable UK figures, see here) – mainly from IEDs – has been acknowledged in the role played by amputees in mission rehearsal exercises and pre-deployment training since 2005 (see here for an excellent general account).

Private contractors like Amputees in Action pride themselves on providing ‘de-sensitising’ exposure to ‘catastrophic injury amputations’ and replicating the latest field injuries for these exercises. There is a risk in re-enrolling war veterans, as the company concedes:

Every amputee is vetted and put through specialist training beforehand to see if they are up to the job. For some it is too close to the mark, too realistic. The last thing we want to do is traumatize someone, stymie their rehabilitation.

These simulations have been used to prepare ordinary soldiers for the situations they will face – today it’s not only the ‘golden hour’ between injury and surgery that is crucial but also (and much more so) the ‘platinum ten minutes’ immediately following the incident, so the first response is vital. They have also been used to ready trauma teams for the war zone: the BBC has a report on the Royal Army Medical Corps’s mock ‘Camp Bastion’ at Strenshall in Yorkshire here.

These various exercises incorporate the latest advances in evacuation and trauma care, which have meant that today’s soldiers are far more likely to survive even the most life-threatening wounds than those who fought in previous conflicts, but the horrors experienced by young men and women in the military who lose arms and legs – sometimes all of them – are truly hideous: read, for example, Anne Jones‘s mesmerising and deeply moving account of They Were Soldiers: How the wounded return from America’s wars (you can get an idea from her ‘Star-spangled Baggage’ here). Their road to rehabilitation is far longer, and infinitely more painful, than the precarious journey through which they returned to the United States (see also my ‘Bodies on the line‘).

Researchers unveiled the world’s first thought-controlled bionic leg on 25 September 2013 funded through the US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command’s (USAMRMC) Telemedicine and Advanced Technology Research Center (TATRC) and developed by researchers at the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago (RIC) Center for Bionic Medicine.

There is some light in the darkness – ongoing experiments with state-of-the-art, ‘bionic’ prosthetics animated by microprocessors in the US, the UK and elsewhere that restore far more stability, mobility and movement than would have been possible even five years ago (see above, and here and here for the US, here and here for the UK). In the 1980s less than 2 per cent of US soldiers who had suffered major limb amputations returned to duty; by 2006 that had increased to over 16 per cent (see also here and here). There are several reasons for the change, but in 2012 Jason Koebler reported:

According to the Army, at least 167 soldiers who have had a major limb amputation (complete loss of an arm, leg, hand, or foot) have remained on active duty since the start of the Afghanistan and Iraq wars, with some returning to battle. Many others have returned overseas to work in support roles behind the lines.

“When we have someone we know wants to return, their rehab is geared that way,” says John Fergason, chief of prosthetics at the Army Center for the Intrepid at Fort Sam in Houston, Texas.

Kevin Carroll, vice president of Prosthetics at Hanger, a company that makes artificial limbs, says prosthetics have become more comfortable to wear and closer in range of motion to natural limbs. “Unfortunately, when you have war, you have casualties, but with that comes innovation,” he says. Artificial joints are getting better at approximating the knee, elbow, wrist, and ankle, and microprocessors embedded in prostheses are able to pick up and adjust for impacts from walking, running, jumping, and climbing.

“The person doesn’t have to worry about the prosthetic device, they’re worrying about the task in front of them,” Carroll says. “If they want to go back to be with their troops, that’s an option for many soldiers these days.”

Notice, though, that these advances in prosthetic design and manufacture are part of an intimate conjunction between military violence and military medicine, in which materials science, bio-engineering, electronics and computer science simultaneously provide new means of bodily injury and new modalities of bodily repair. This is captured in the title of David Serlin‘s thought-provoking essay, ‘The other arms race’ [in Lennard Davis (ed), The Disability Studies Reader (second edition, 2006) 49-65; this essay is not included in the latest edition, but see also the collection David edited with Katherine Ott, Artificial parts, practical lives: modern histories of prosthetics (2002) and his own Replaceable You: engineering the body in postwar America (2004)]. You can also find an excellent brief historical review of ‘Prosthetics under trials of war’ here.

And, given the circuits within the military-medical machine, there may be more to come. There are those who anticipate a future in which prosthetics will not only reinstate but also increase a soldier’s capabilities. Koebler cites Jonathan Moreno, a bioethicist at the University of Pennsylvania, who ‘talks about a future where prosthetics are “enhancers” that allow soldiers to be stronger, faster, and more durable than their peers.’ These fantasies feed through the masculinist imaginary of the post-human cyborg soldier (sketched an age ago by Chris Hables Gray and revisited here) to the prosthetics of military violence with which I began. Here Tim Blackmore‘s War X: Human extensions in battlespace (2011) is also relevant.

And, given the circuits within the military-medical machine, there may be more to come. There are those who anticipate a future in which prosthetics will not only reinstate but also increase a soldier’s capabilities. Koebler cites Jonathan Moreno, a bioethicist at the University of Pennsylvania, who ‘talks about a future where prosthetics are “enhancers” that allow soldiers to be stronger, faster, and more durable than their peers.’ These fantasies feed through the masculinist imaginary of the post-human cyborg soldier (sketched an age ago by Chris Hables Gray and revisited here) to the prosthetics of military violence with which I began. Here Tim Blackmore‘s War X: Human extensions in battlespace (2011) is also relevant.

But Koebler is quick to add that all this is still a distant prospect:

“I know the question is often, ‘How close are we to true bionic or having artificial limbs that are more versatile than natural ones?'” Fergason says. “Frankly, we’re not that close. You’re not going to see anyone decide, ‘Boy, I think I’d like to get a bionic leg because they’re so fantastic.’

“We love to read about the super-soldier, but that’s not the case right now. Amputation is so complex in what it does to your body that it’s a very long recovery,” he adds.

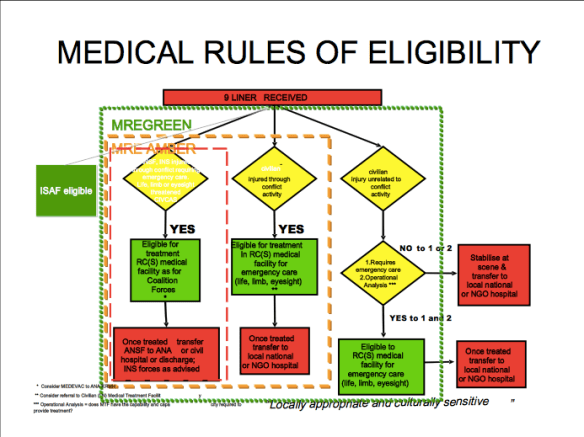

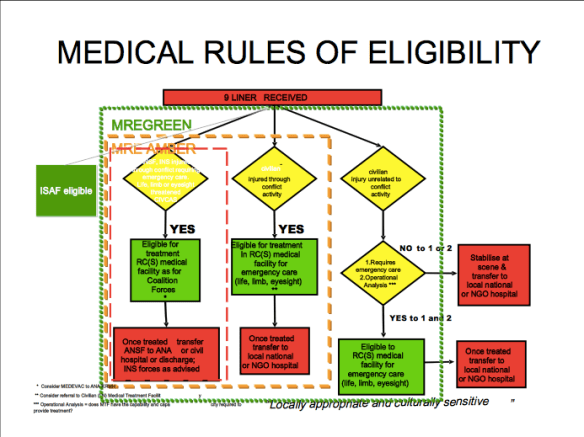

So what, then, of civilians? Under ISAF’s Medical Rules of Eligibility Afghan civilians who were injured during military operations and/or needed ‘life, limb or eyesight saving care’ could be admitted to the international medical system, and were eligible for emergency casualty evacuation and treatment at one of the Category III advanced trauma centres at Bagram or Camp Bastion.

As soon as possible, however, Afghans were to be treated by Afghans and so, after surgical intervention they had to be transferred to the local healthcare system. The same applied to the Afghan National Army and police. In consequence, the drawdown of international forces – which also includes their medevac and trauma teams – has left the local population desperately vulnerable to the after-effects of continuing and residual military and paramilitary violence (see here and here).

The inadequacies and insufficiencies of the Afghan healthcare system have prompted a number of NGOs to fill the gap between the radically different systems, and they have done – and continue to do – immensely important work.

But compare the prosthetics available to US soldiers with those supplied to Afghan civilians. I don’t mean to minimise the invaluable work done by hard-pressed and underfunded NGOs, but the image below is from the ICRC‘s Orthopedic Center in Kabul (see also here). There are other centres supported by the ICRC in Faizabad, Gulbahar, Herat, Jalalabad, Lashkar Gah, and Mazar-e-Sharif, together with a manufacturing facility in Kabul, and other NGOs are active elsewhere – Médecins sans Frontières runs a similar facility in Kunduz, for example.

In addition to these facilities, there have been some ingenious work-arounds. Carmen Gentile describes how US soldiers at Forward Operating Base Kasab in Kandahar were moved by the plight of Mohammed Rafiq, an eight-year old boy whose legs were blown off by an IED. ‘Since we couldn’t get a supply of commercially made legs, we decided that maybe we could make them ourselves,’ explained Major Brian Egloff, a US Army surgeon at the base.

Using scrap tubing and some ingenuity, Egloff fitted Rafiq with small prosthetic legs. Rafiq was now able to get around the village…

Egloff did not end his work with Rafiq. He knew there must be other amputees living in the area… Soldiers on patrol had noticed “a lot of guys with amputations that had no prosthetic legs and were reduced to crawling around on the ground and relying on the charity of strangers just to get by,” he says. Afghans heard about what was done for Rafiq and asked for help for others. Egloff made the legs from material readily available in any welding shop, he says, mostly scrap aluminum tubing for the legs and aluminum plates for the prosthetic feet. A spring-loaded hinge served as the ankle joint. “It’s a very simple design, nothing complicated,” he says.

These legs were intended to be temporary replacements until ‘a professionally fitted prosthetic’ was available, but the same report notes that ‘getting to a provincial capital, where most hospitals are located, is not easy for many Afghans and the routes are dangerous.’ There’s much more about inaccessibility in MSF’s Between rhetoric and reality: the ongoing struggle to access healthcare in Afghanistan (February 2014).

Like Mohammed – and many ISAF and Afghan soldiers – many of these amputees are the victims of IEDs or even land mines left over from the Soviet occupation (for a global review of the rehabilitation of people maimed by the explosive remnants of war [ERW], see this 2014 report from the International Campaign to Ban Landmines–Cluster Munition Coalition).

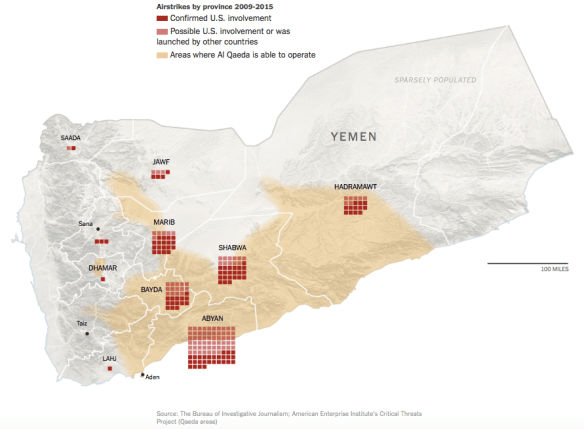

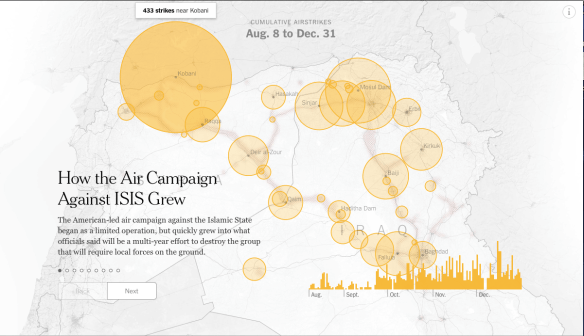

But some of them will be the victims of air strikes from or orchestrated by Predators and Reapers: in recent years Afghanistan has been the most heavily ‘droned’ theatre of operations in the world. In some cases they were caught in the blast, but in others they were the victims of what Rob Nixon calls ‘slow violence‘. According to a report by Sune Engel Rasmussen in the Guardian:

Since 2001, the coalition has dropped about 20,000 tonnes of ammunition over Afghanistan. Experts say about 10% of munitions do not detonate: some malfunction, others land on sandy ground. In rural areas, children often bring in vital income to households, but collecting scrap metal or herding animals can be fraught with unpredictable risks. Of all Afghans killed and maimed by unexploded ordnance, 75% are children…

Their future is usually bleak. Erin Cunningham reports that ‘even as the population of Afghans who are missing limbs grows, amputees face discrimination and the harsh stigma of being disabled.’

“Socially and financially, their lives are destroyed,” Emanuele Nannini, program director at the Italian nonprofit Emergency, which operates health-care centers across Afghanistan, said of Afghan amputees.

From January to June [2014], Emergency’s Center for War Trauma Victims in Lashkar Gah, the capital of Helmand province in southern Afghanistan, performed 69 amputations. The fiercest fighting between the two sides usually takes place in the warmer summer months.

Emergency then sends the amputees to the nearby International Committee for the Red Cross orthopedic facility for long-term rehabilitation. The patients receive vocational training and other support to reintegrate them into society. The ICRC said that between April and June this year, it admitted 351 amputee patients to its facilities across Afghanistan.

But for the most part, amputees “are completely dependent on their families, and they become a huge burden,” said Nannini, who is based in Kabul. “The real tragedy starts when they go home. If they don’t have a strong family, they become beggars.”

Emergency runs two other surgical centers, in Kabul and Anabah, as well as a number of clinics and first aid posts in the villages; at Lashkar Gah six out of every ten admissions are victims of bombs, land mines or bullets.

The story is, if anything, even worse across the border in Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas, whose inhabitants are also subject to explosive violence from the Taliban and other groups, and from CIA-directed drone strikes and air and ground attacks by Pakistan’s military. As Madiha Tahir has shown, the victims usually disappear from public attention, at least in the United States:

What is the dream?

I dream that my legs have been cut off, that my eye is missing, that I can’t do anything … Sometimes, I dream that the drone is going to attack, and I’m scared. I’m really scared.

After the interview is over, Sadaullah Wazir pulls the pant legs over the stubs of his knees till they conceal the bone-colored prostheses.

The articles published in the days following the attack on September 7, 2009, do not mention this poker-faced, slim teenage boy who was, at the time of those stories, lying in a sparse hospital in North Waziristan, his legs smashed to a pulp by falling debris, an eye torn out by shrapnel….

Did you hear it coming?

No.

What happened?

I fainted. I was knocked out.

As Sadaullah, unconscious, was shifted to a more serviceable hospital in Peshawar where his shattered legs would be amputated, the media announced that, in all likelihood, a senior al-Qaeda commander, Ilyas Kashmiri, had been killed in the attack. The claim would turn out to be spurious, the first of three times when Kashmiri would be reported killed.

As Sadaullah, unconscious, was shifted to a more serviceable hospital in Peshawar where his shattered legs would be amputated, the media announced that, in all likelihood, a senior al-Qaeda commander, Ilyas Kashmiri, had been killed in the attack. The claim would turn out to be spurious, the first of three times when Kashmiri would be reported killed.

Sadaullah and his relatives, meanwhile, were buried under a debris of words: “militant,” “lawless,” “counterterrorism,” “compound,” (a frigid term for a home). Move along, the American media told its audience, nothing to see here. Some 15 days later, after the world had forgotten, Sadaullah awoke to a nightmare.

Do you recall the first time you realized your legs were not there?

I was in bed, and I was wrapped in bandages. I tried to move them, but I couldn’t, so I asked, “Did you cut off my legs?” They said no, but I kind of knew.

Zeeshan-ul-hassan Usmani and Hira Bashir listed some of the long-term implications in a report completed last December for the Costs of War project:

Drone injuries are catastrophic ones. Wounded survivors of drone attacks have often lost limbs and are usually left with intense and unmanaged pain, and some desire death. Those who survive with severe disabilities face a difficult situation given lack of accommodation for people with disabilities in Pakistan. FATA is an extremely difficult terrain for a disabled person. A walk out for the morning naan (traditional bread) may require navigating through a twisty mud track, with regular dips and bumps. The traditional mud houses of the area themselves have a mud floored haweli (an open-air area onto which all the rooms usually open up). A person with a leg amputation cannot use a regular wheel chair, go to school or hospital, or even use a toilet on his own. Disability of the primary breadwinner can change the course of life for an entire family, since most village jobs are physical ones.

Here too the barriers are more than physical. In 2011 Farooq Rathore and Peter New described how disability remains a stigma in many sectors of Pakistani society, and rehabilitation medicine is still underdeveloped.

The leading prosthetics center is the Armed Forces Institute for Rehabilitation Medicine at Rawalpindi – whose rehabilitation services for injured soldiers are reportedly ‘the best in the country‘ – but it ‘still manufactures prostheses and orthoses with wood, leather, and metal.’ For injured civilians, the outlook is still more grim. In 2012 a plan was announced to appoint orthotic specialists and physiotherapists at district hospitals throughout the FATA:

The prolonged United States-led war against terrorism has left a large number of people disabled in Pakistan, compelling the government to institute a rehabilitation plan that will include imparting vocational skills…

“We plan to enhance the physical rehabilitation services for the victims of terrorism to save them from permanent disability,” [Mahboob ur Rehman, head of the physiotherapy department at the Hayatabad Medical Complex (HMC)in Peshawar] told IPS.

The decade-long armed conflict has resulted in injuries to thousands of people from blasts, shelling and drone attacks, with the majority of the victims needing prosthetic and orthotic management to help regain the ability to walk, he said.

But it turns out that the emphasis is as much on ‘wheelchairs and sewing machines’ as it is on even the most basic prosthetics.

Once again, NGOs have provided vital services in the most difficult circumstances. In 1979 the ICRC established a Paraplegic Rehabilitation Center in Peshawar for victims of the Afghan war, for example, which was subsequently transferred to the control of the Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa provincial government. It has achieved some notable successes, but here too the focus is on physical therapy and it is outside the FATA so that access is difficult for many people.

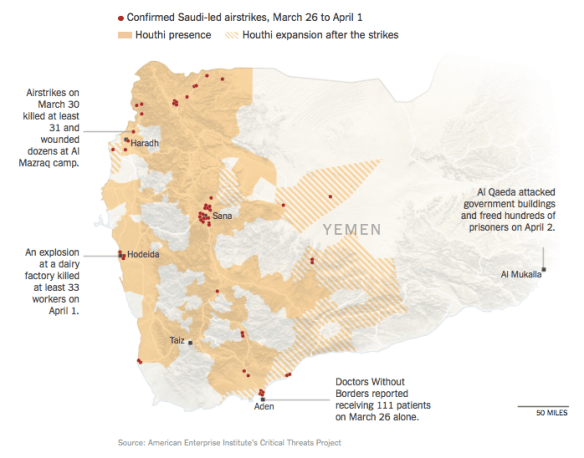

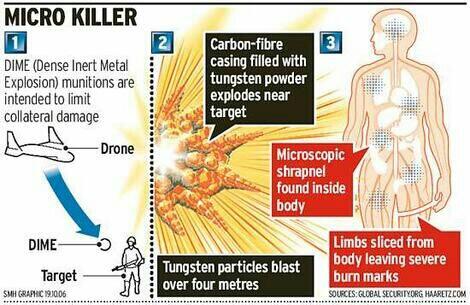

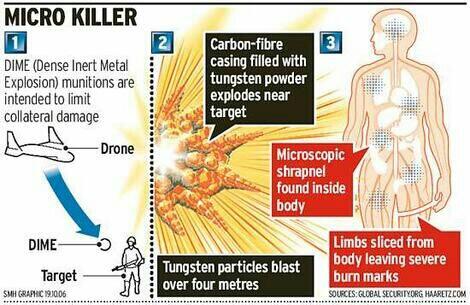

And so, finally, to Gaza. Here the differences with Afghanistan and Pakistan are striking. Throughout the Israeli assault last summer, as I showed in detail here, medical services were severely compromised, and hospitals and medical centres actively targeted. The only rehabilitation hospital, El-Wafa, was destroyed. The injuries were also aggravated by the use of Dense Inert Metal Explosives (DIME) – developed for the US Air Force in 2006 – and which, according to a Briefing Note issued by the Palestinian human rights organisation Al-Haq, were fired from Israeli drones.

These experimental weapons are supposed to decrease collateral damage by constricting the lethal blast radius. But inside that perimeter the explosive blast is concentrated and magnified:

The injuries of victims who have been in contact with experimental DIME weapons are distinguishable from injuries sustained by non-experimental weapons. While signs of solid shrapnel or metal fragments are typical of amputations sustained from traditional explosives, physicians in the Gaza Strip are witnessing gruesome amputations caused by a metal vapor or residue which indicate the detonation of an extreme force in a small radius. In fact, as a result of these weapons, reported cases in the Gaza Strip include entire bodies cut in half, shattered bones, and skin, muscle and bones turned into charcoal due to the destructive burns associated with the weaponry’s extreme force and high temperature.

The lacerations are so severe that many victims bleed out and die.

The scale of destruction in Gaza also presents a radically different landscape for survivors of blast injuries. If the terrain in FATA is formidably difficult for anyone using prosthetics or in a wheelchair, imagine what it must be like to be confronted with this:

When you look at that, bear in mind that when the assault came to an end there were still around 7,000 unexploded bombs and other explosive remnants of war beneath the rubble.

These are all dreadful effects and yet, compared to Afghanistan and Pakistan, the situation for prosthetics and rehabilitation seems somewhat better. The prosthetics are more advanced, and some patients have been able to travel to Beirut, Amman and on occasion into Israel for treatment. But there are still formidable obstacles in the essential provision of continuing local care. Bayan Abdel Wahad reports from the Artificial Limb Centre, the only one of it kind in Gaza:

The number of patients who have benefited from the service of prosthetic replacement which the Centre provides for free is about 300 people who have been injured as a result of the Israeli bombardments in the past five years. However, a number of people injured in the last war – Operation Protective Edge – have not been able to come to the center yet because they are still bed-ridden due to several injuries whose treatment takes precedence over prosthetic replacement…. The technical coordinator at the center, Nivine al-Ghusain, said that “despite all the difficulties we face in funding and getting the materials necessary to manufacture the artificial limbs, we will continue in our work.” She [said] that the Centre takes upon itself the maintenance of the prosthesis from time to time “in addition to changing it based on the patients’ needs.”

The Centre relies on the ICRC for components and raw materials from France, Germany, Switzerland and the United States, but there are continuing difficulties in importing these via Israel or Egypt. In December 2014 the Center was treating around 950 amputees.

Reports about the cultural and social response to these visible victims of military violence are mixed. Guillaume Zerr, who directs Handicap International’s operations in Gaza, told Reuters that ‘there can be less acceptance of their condition than in other regions of the world’, whereas one young man – a double amputee – insisted that ‘I feel more love, support and sympathy from people now than before my injuries, and Gazan society is non-discriminating toward me.’ Perhaps this is, at least in part, because he, like others wounded in Gaza, can provide an unambiguous narrative, ‘to tell the story behind the loss of his legs’. I remember Omar Dewachi explaining to me how patients from Iraq, Libya or Syria who are treated in Beirut for their wounds have to return home with a narrative that can explain what happened to them in terms that will satisfy whichever side in those civil wars might call them to account. Such narratives are important not only for their rehabilitation (and here they are vital) but also for their very survival. This is presumably more straightforward in Gaza, but this ‘politics of the wound’ is also always a geopolitics of the wound.

One last thought. I’m struck by how often the term ‘asymmetric war’ is used to imply that conflicts of this sort are somehow unfair – to those who possess overwhelming firepower. But war is about more than firepower, more even than killing, and I hope I’ve shown that the differences between the continuing care and rehabilitation available to those who are maimed in these wars reveal not only a different prosthetics of military violence but also a new and grievous asymmetry in its enduring consequences.