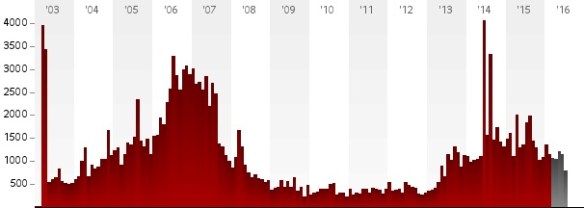

This is the first in a new series of posts on military violence against hospitals and medical personnel in conflict zones. I’ve discussed these issues on multiple occasions in the past – in relation to Afghanistan, Gaza and Syria – but I’m now working towards a presentation – and ultimately an extended essay – that brings this all together (including a detailed analysis of the US air strike on the MSF Trauma Centre in Kunduz). It will have its first outing (“Surgical Strikes and Modern War”) at NUI Galway next month.

It was a clear, moonlit night and the hospitals – many of them provided by humanitarian organisations – were brightly lit as the nurses moved about the wards caring for their patients; elsewhere the hard-pressed surgeons were still operating on the maimed bodies of the wounded. At 10 p.m. they heard the sound of approaching aircraft: first the clatter of gunfire and then, after the hospitals were plunged into precautionary darkness, the whistle of bombs falling. The hospitals were hit repeatedly, and two hours later – when the flames had burned themselves out and the smoke cleared – several nurses had been killed and hundreds of patients had been killed or injured; multiple wards had been severely damaged. Ten days later the aircraft returned; one hospital was totally destroyed and elsewhere operating rooms and wards were destroyed or damaged.

The scene is all too familiar: but this is not Gaza in 2014, Afghanistan in 2015 or Syria in 2016. This is Étaples on the coast of France, 25 km south of Boulogne, in May 1918.

On the Western Front it was common for stretcher-bearers to come under fire as they retrieved the wounded from No Man’s Land or carried them through the trenches and down the roads to aid posts and dressing stations; those places were often shelled since they were close to the front lines. On 13 September 1914 Travis Hampson – a Medical Officer with a Field Ambulance – noted:

As one of our buses drove out onto the road to pick up some wounded gunners from the battery opposite, one landed on the road in front of it, and one behind, but not near enough to do any damage. With their glasses they must have been able to distinguish the white tilt and red cross, but we can’t grumble about being shelled if we are put amongst ammunition columns and batteries.

So too with the Casualty Clearing Stations (CCS) which had moved close to the front lines to speed up the treatment of what were often catastrophic wounds and to minimise the risk of infection. Here is Kate Luard writing in her diary at Brandhoek on 18 August 1917:

He [the enemy] played about all night till daylight. There were several of him. He went to C.C.S.’s behind us. At one he wounded three Sisters and blew their cook-boy to pieces. The Sisters went to the Base by Ambulance Train this morning. At the other he wounded six Medical Officers among other casualties. A dirty trick, because he has maps and knows which are hospitals back there. Here we are in a continuous line of camps, batteries, dumps, etc., and he may not know.

In fact, her CCS was judged to be too close for comfort and was ordered to evacuate a few days later.

Luard’s last sentence reinforces Hampson’s; in general (so she suggests) the Red Cross was respected. The following year she wrote about German air raids on the CCS:

Jerry comes every night again and drops below the barrage, seeking whom he may devour: I think he gets low enough to see our huge Red Cross, as even when some of our lads butt in and engage him with their machine-guns, he hasn’t dropped anything on us.

For the most part, then, it seems that attacks on medical sites and personnel were the result of the inaccuracy of shellfire and bombing (especially at night) compounded by the close proximity of aid posts, dressing stations, CCS and ambulance trains to the fighting.

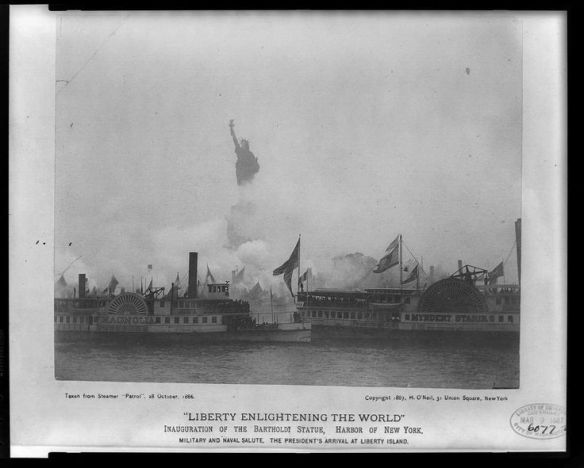

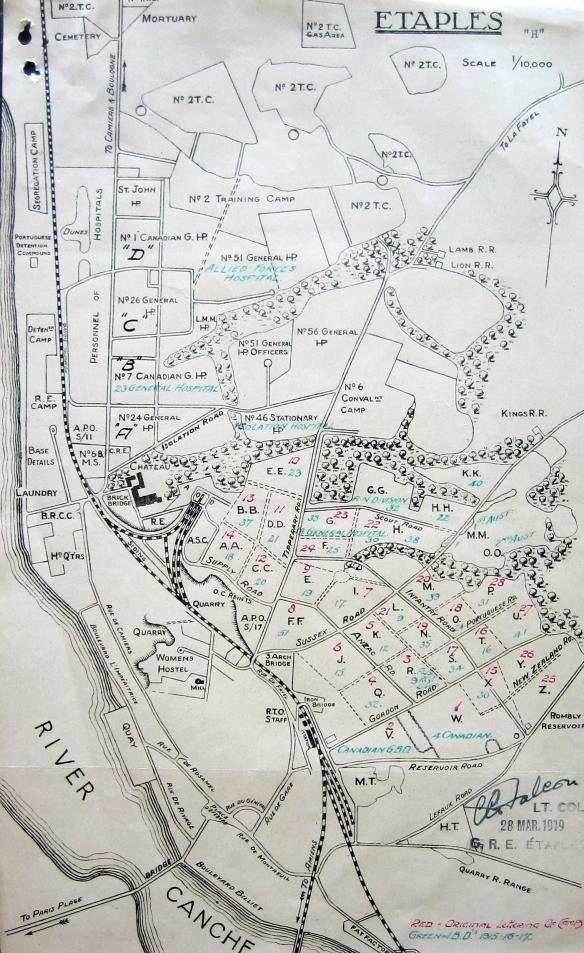

Yet the hospital raids in the last year of the war seemed to be something else. Étaples was distant from the fighting, the site of a vast collection of ‘base hospitals’ – ‘the Land of Hospitals’, Sister Elsie Tranter called it, ‘a stretch of six kilometres of hospitals’ – to which wounded soldiers were sent from casualty clearing stations near the rapidly moving front: some to be treated and returned to active service, others to be evacuated across the Channel on hospital ships.

As soon as the news broke, the British press were up in arms at what the Times lost no time in calling ‘German savagery at its worst’:

‘During the recent fine weather our airmen have … made every use of the still air and the good visibility to attack and harass the enemy by bombing his camps, billets, rail-heads, batteries, dumps, roads and all points of military importance in the battle area and immediately behind. At the same time, the German airmen have also been making use of the favourable conditions by having recourse to their old trick of bombing hospitals.

‘There is one place in France, faraway from the battle area, where we have a large group of hospitals. The hospital tents there cover a great area of ground. The Germans are perfectly aware of the character of the place, and they selected it as the object of a bombing raid last year. They have again been attacking it, and the size of the tract of ground covered with hospital outfits and the entire absence of any concealment make it a mark which no airman could possibly miss. An airman blind and drunk could let bombs fall from any height in any wind and weather, and they must land somewhere amongst the attendants’ quarters or on the tents where the nursing sisters move among the rows of cots with their helpless occupants.

‘On Sunday night the Germans attacked the place with all the ferocity of which they are capable… The scenes inside the tents were of the most piteous description, and the total casualties to patients, sisters, medical officers and attendants must have far exceeded those of any London air raid. The redeeming feature of the whole horrible affair was the magnificent behaviour of the hospital staff…’ [Times, 24 May 1918]

This too is a familiar narrative, and one that would be repeated in countless wars to come: ‘we’ attack military targets with precision, ‘they’ attack civilian targets with abandon; their aircrew are cowards, our victims are heroes.

The press provided photographic evidence of the aftermath of the raids:

One of the German pilots was shot down – ‘and is now being cared for in the hospital he bombed’, thundered the Times – and his protestations were summarily dismissed:

‘He tried at first to excuse himself by saying that he saw no Red Cross. When challenged with the fact that he knew that he was attacking hospitals he endeavoured to plead that hospitals should not be placed near railways, or if they are, they must take the consequences. Apart from the fact that hospitals must be near railways for the transport of their patients, in this case, as in the others, the raiders were not attacking the railway but came deliberately to bomb the hospital.’

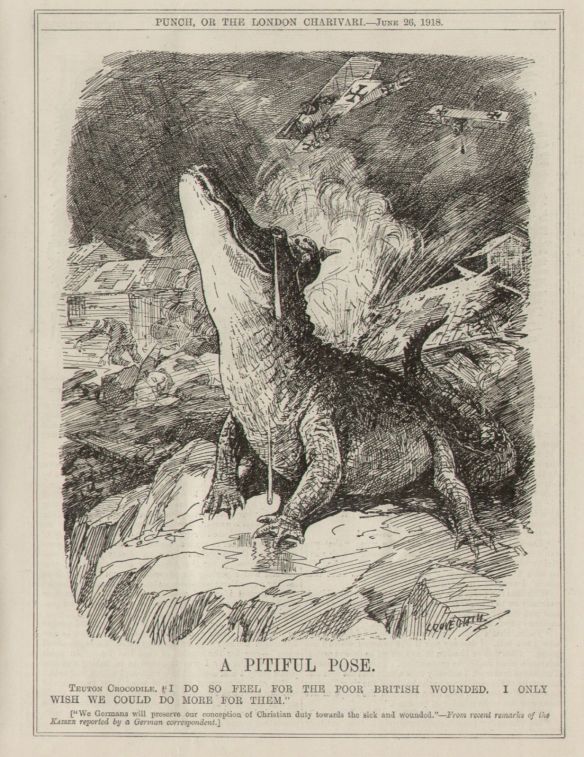

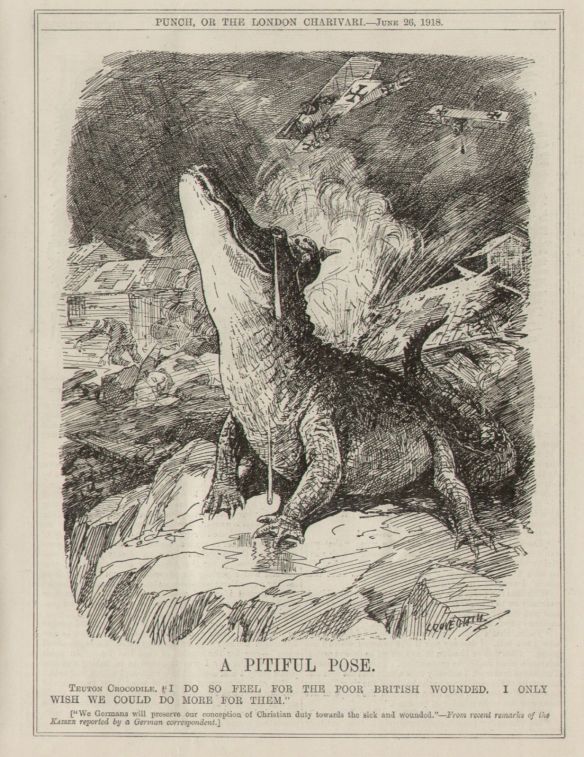

Punch dismissed German remorse as crocodile tears:

There were repeated angry calls for reprisals. Arthur Conan Doyle urged that the captured pilot be shot ‘with a notice that such will be the fate of all airmen who are captured in such attempts’ and recommended that German prisoners of war ‘at once be picketed among the tents’ to deter future raids [Times, 27 May 1918]. Sir James Bell went further. Although his son had been killed in one of the raids, reprisals were not about revenge, he said, but were a strictly ‘military matter’. He recommended ‘bombing German hospitals and killing their wounded’ to stop the outrages [Times, 5 June 1918].

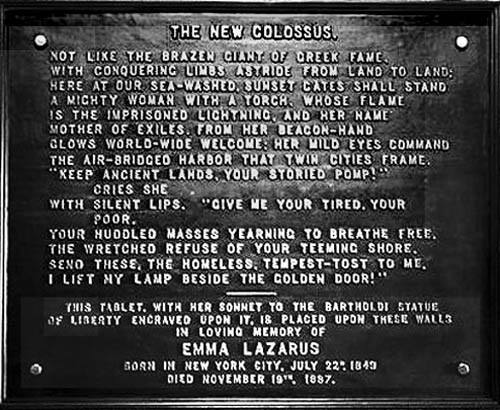

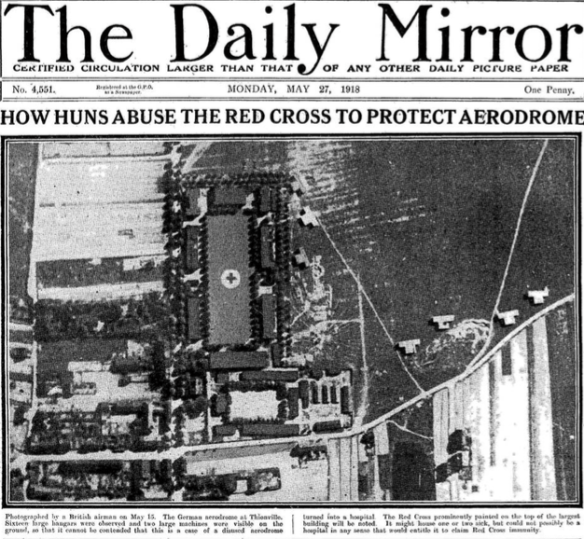

Finally, the press trumped arguments about the presence of Red Crosses on the hospitals. The Hague Convention required belligerents to take ‘all the necessary measures … to spare, as far as possible, … hospitals, and places where the sick and wounded are collected, on the understanding that they are not being used at the same time for military purposes’ and required them to mark such places with ‘distinctive and visible signs’.

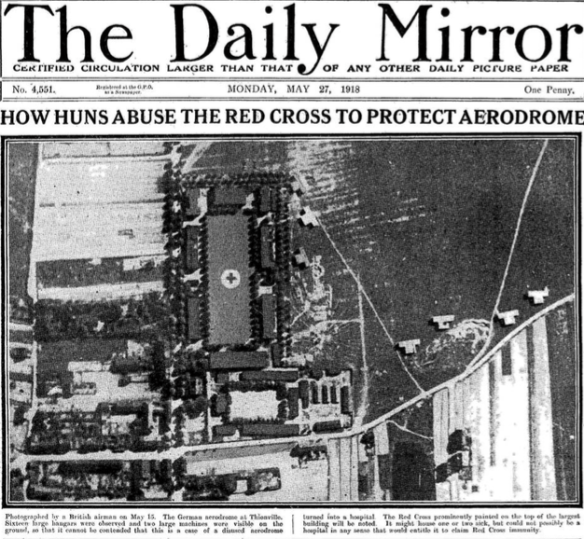

But far from respecting these protocols there was photographic evidence that the Germans were abusing the Red Cross to protect their own military installations:

The aerial photograph was taken on 15 May 1918, and the caption described this as an active aerodrome at Thionville; the large building displaying the Red Cross ‘might house one or two sick’ but the Mirror insisted it ‘could not possibly be a hospital in any sense that would enable it to claim Red Cross immunity.’

And so, in her diary entry for 24 June 1918, Sister Edith Appleton wondered

‘if there is any truth in what they say about the bombing of hospitals – that in German territory the flying men have seen what are without doubt aeroplane hangers and ammunition dumps marked with huge red crosses. They are not near a railway and are so placed that they simply cannot be hospitals. I suppose they think we do the same and they bomb us on the chance of it. Of course we bomb their hangers and dumps – we should be fools if we didn’t! I am quite sure though that they do know what is a real hospital. They can see the wounded men walking about and some lying out in beds.’

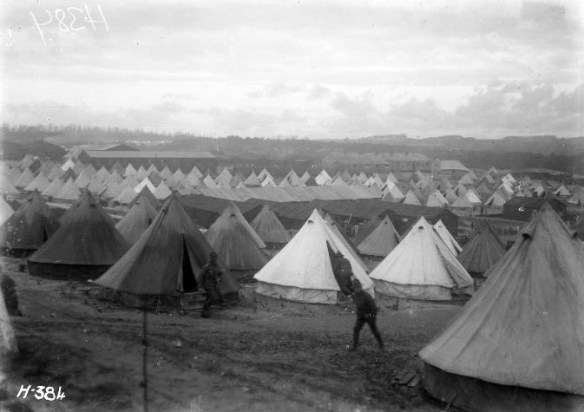

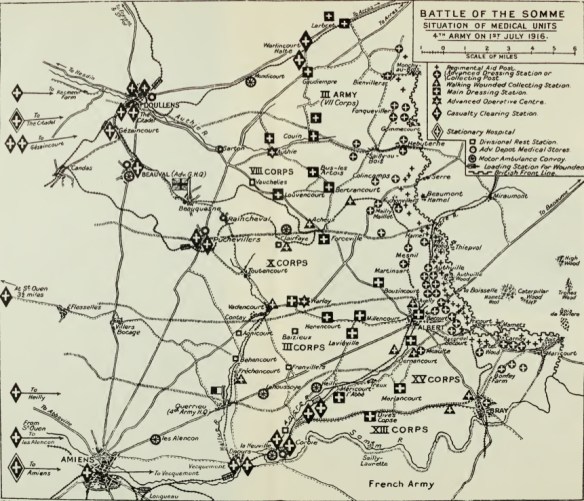

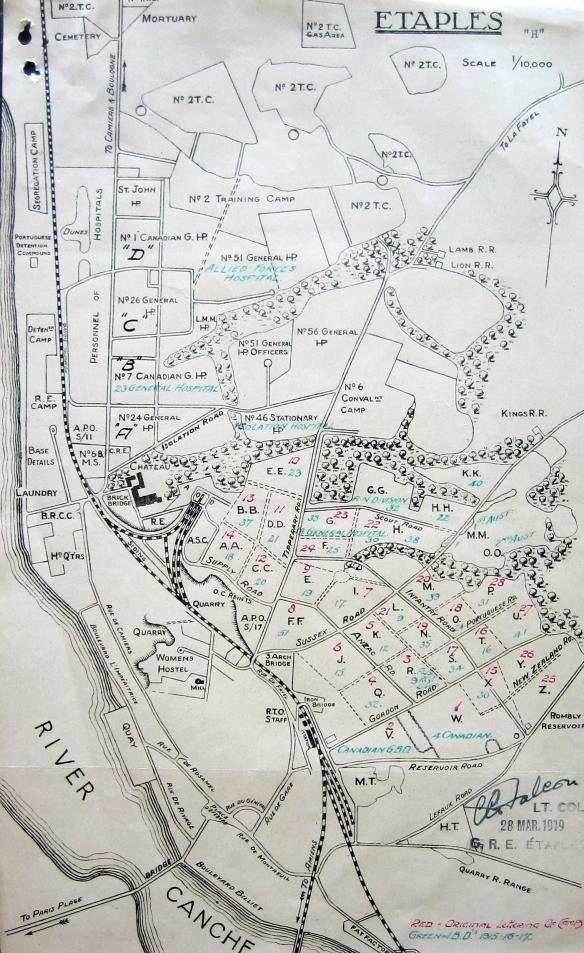

Yet the press reports were studiedly disingenuous. Étaples was indeed physically removed from the fighting – ‘far away from the battle’, as the Times‘s correspondent noted – but it was functionally and logistically absolutely central to the Allied military machine because it was the site of multiple Infantry Base Depots. It was a vital transit and training camp – all those ‘TCs’ scattered across the map (above).

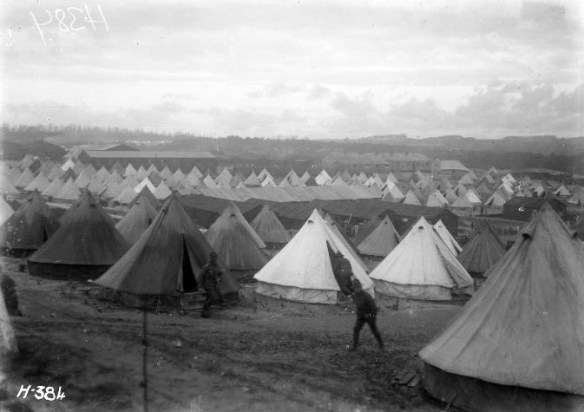

‘The Base!’ Edmund Blunden exclaimed in Undertones of War: ‘dismal tents, huge wooden warehouses, glum roadways, prisoning wire.’ He associated it, ‘as millions do, with “The Bull-Ring”, that thirsty, savage, interminable training-ground’ among the dunes where new recruits and newly discharged patients were put through their paces and ‘toughened up’ by unrelenting instructors. When American military surgeon Harvey Cushing drove past its camps in 1917 they were ‘full of men rushing about like so many ants and all the color of the soil; drilling in the sand, practicing with machine guns, throwing bombs [grenades], having bayonet exercise, digging trenches and I know not what all.’ [For a thoughtful account of the oppressive conditions endured by troops during their two-week stints at the base and their contribution to the mutiny of 1917, see Douglas Gill and Gloden Dallas, ‘Mutiny at Étaples base 1917’, Past and Present 69 (1975) 88-112: ‘A corporal encountered several men returning to the front with wounds which were far from being healed. “When I asked why they had returned in that condition they invariably replied: ‘To get away from the Bull Ring’.”‘]

In a letter to his mother Wilfred Owen described the base as ‘a vast, dreadful encampment’:

It seemed neither France nor England, but a kind of paddock where the beasts are kept a few days before the shambles [slaughter] … Chiefly I thought of the very strange look on all the faces in that camp; an incomprehensible look, which a man will never see in England …; nor can it be seen in any battle. But only in Étaples. It was not despair, or terror, it was more terrible than terror, for it was a blindfold look, and without expression, like a dead rabbit’s.

The training camps were a sea of bell tents (below) – like many of the hospitals – and the captured airmen insisted that this had been their objective: ‘the number of bell tents convinced them this was not [a hospital] as patients would not be in bell tents.’

Étaples had been targeted before. Vera Brittain, who was a nurse with the Voluntary Aid Detachment at No 24 General Hospital, described the ‘ceaseless and deafening roar [that] filled the air’ during the German offensive in the spring: ‘Motor lorries and ammunition waggons crashed endlessly along the road; trains with reinforcements thundered all day up the line, or lumbered down more slowly with their heavy freight of wounded…’

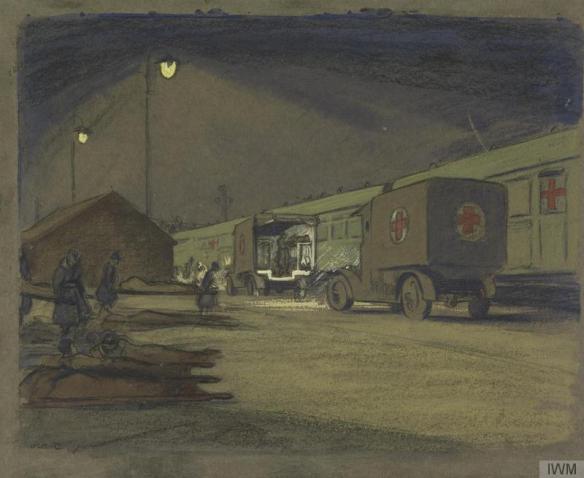

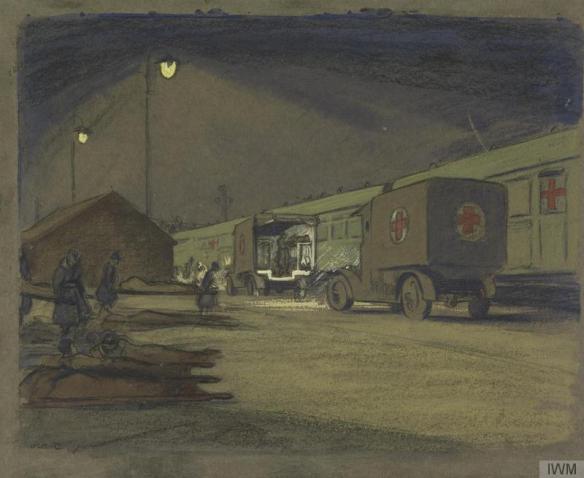

Images like this painting (above) by Olive Mudie-Cooke – a VAD convoy unloading an ambulance train at Étaples – are immensely powerful, but they ought not to blind us to the movement of men and matériel in the other direction. As Vera Brittain knew only too well, there were in consequence frequent air raids on the lines of communication:

Certainly no Angels of Mons were watching over Etaples, or they would not have allowed mutilated men and exhausted women to be further oppressed by the series of nocturnal air-raids which for over a month supplied the camps beside the railway with periodic intimations of the less pleasing characteristics of a front-line trench. The offensive seemed to have lasted since the beginning of creation, but must have actually been on for less than a fortnight, when the lights suddenly went out one evening… Instead of the usual interval of silence followed by the return of the lights, an almost immediate series of crashes showed this alarm to be real…

Gradually, after another brief burst of firing, the camp became quiet, though the lights were not turned on again that night. Next day we were told that most of the bombs had fallen on the village; the bridge over the Canche, it was reported, had been smashed, and the train service had to be suspended while the engineers performed the exciting feat of mending it in less than twelve hours.

The bridge was of overwhelming strategic importance: by the time of the spring offensive a hundred military trains were passing over it every day. Here is H.A. Jones in the official history of The war in the air (citing Colonel M.G. Taylor):

The enemy advance against the British on the Somme and on the Lys in March and April had endangered the railway system. ‘The culmination was reached in May 1918, when the great lateral line from St. Just, via Amiens, to Hazebrouck had to be abandoned as a railway route owing to enemy shell fire. Our armies were then penned into a narrow strip of country, possessing only one lateral railway communication, through Abbeville and Boulogne. Most of the forward engine depots had been lost, and several of the important engine depots remaining were so close to the enemy as to be practically useless, and our one lateral, along which all reserves and reinforcements drawn from one part of the front to be thrown in at another had to be moved, was threatened daily and nightly by persistent air attacks on the bridge over the Canche river at Etaples.‘

The Germans knew the importance of destroying, and the British of protecting, this line of communications.

Vera Brittain had returned to London when the Times published its report on the air raids in May. ‘It was clear from the guarded communiqué that this time the bombs had dropped on the hospitals themselves,’ she wrote, ‘causing many casualties and far more damage than the breaking of the bridge over the Canche in the first big raid.’ Cushing also recorded the enormity of the raid:

Étaples has had a bad hit – much worse than we had supposed… For two hours the raiders kept it up, returning again and again like moths around a flame.

But he knew Étaples of old and reckoned the objective was the same as before: not even the camps but the railway. ‘They were doubtless after the railroad and perhaps the bridge half a mile below.’

The official British history was similarly unequivocal:

During the night of the 19th/20th of May, at the time when the last of the German aeroplane raids was being made on London, fifteen bombers attacked the Etaples bridge. Only one bomb fell close and this did no damage: most of them exploded in neighbouring hospitals and camps with terrible effect… One of the German bombers was shot down, and the captured crew insisted that they did not know that hospitals were situated near the railway. They also expressed surprise, not without reason, that large hospitals should be placed close to air targets of first-rate military importance.

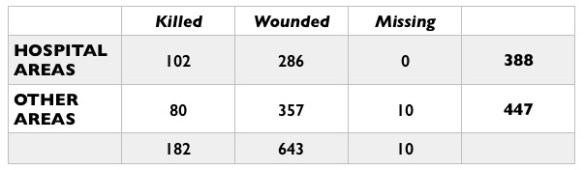

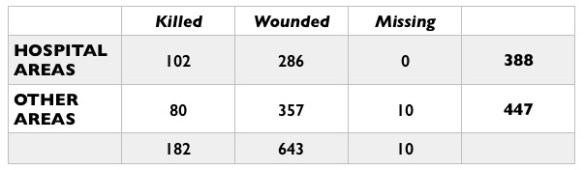

Certainly, the casualties were not confined to the hospital area:

Two Infantry Base Depots suffered direct hits; 53 per cent of military casualties were outside the hospital area.

In fact, behind the scenes the British military and the intelligence service accepted that the hospitals were probably not the intended targets of the raid on 19-20 May or the second raid on 31 May/1 June. Here is the aftermath of that second raid on one Canadian hospital:

Although Sir Douglas Haig firmly believed the hospitals were deliberately targeted in the second raid – he complained that ‘special measures’ had been taken after the air raid on the night of 19-20 May, with ‘Red Crosses repainted so that there could be no possible doubt as to the hospital area’ [see the image below] – Major-General John Salmond [right], who commanded the newly designated Royal Air Force in France, ‘considered it extremely improbable that Red or White Crosses would be distinctly visible at the height from which hostile pilots drop their bombs, usually 5,000 feet or over.’

Although Sir Douglas Haig firmly believed the hospitals were deliberately targeted in the second raid – he complained that ‘special measures’ had been taken after the air raid on the night of 19-20 May, with ‘Red Crosses repainted so that there could be no possible doubt as to the hospital area’ [see the image below] – Major-General John Salmond [right], who commanded the newly designated Royal Air Force in France, ‘considered it extremely improbable that Red or White Crosses would be distinctly visible at the height from which hostile pilots drop their bombs, usually 5,000 feet or over.’

The same (classified) report dated 29 June 1918 conceded that no definitive conclusion could be reached, but its author, the Director of Military Operations at the War Office Sir Percy Radcliffe, was none the less adamant that

We have no right to have hospitals mixed up with reinforcement camps, and close to railways and important bombing objectives, and until we remove the hospitals from vicinity of these objectives and place them in a region where there are no important objectives. I do not think we can reasonably accuse the Germans.

Indeed, Vera Brittain had prefaced her account of the May raids with a revealing rider. ‘The persistent German raiders,’ she wrote, ‘had at last succeeded in their intention of smashing up the Étaples hospitals’ which ‘had so satisfactorily protected the railway line for three years without further trouble or expense to the military authorities‘ (my emphasis). Now she was scarcely a spokeswoman for the British military, but her remark gestures towards the possibility of a remarkably cynical extension of the medical exemption to cover military objectives.

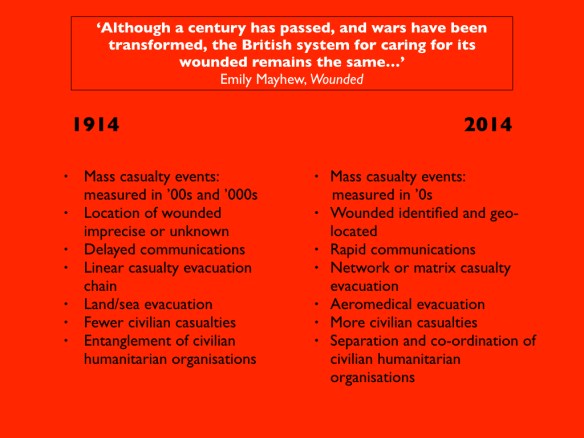

A hundred years later these same arguments about intentionality, accuracy, co-location and the protection (or otherwise) of a Red Cross would reappear in different guises. But they would also be joined by others that revealed an aggressive refusal to accept the principle of medical neutrality at all.

To be continued