Sonia Kennebeck‘s documentary National Bird is previewed in today’s New York Times:

If we can eliminate enemy threats without placing boots on a battlefield, then why not do so? That’s one of the unspoken questions raised, and largely unanswered, by “National Bird,” Sonia Kennebeck’s elegantly unsettling documentary about the United States’ reliance on aerial combat drones.

The weapons themselves, though, demand less of her attention than their psychological impact on three former operators and current whistle-blowers. Identified only by first names (though one full name is visible in a shot of a 2013 exposé in The Guardian), all three were involved in some form of top-secret data analysis and the tracking of targets. Justifiably nervous, they wear haunted, closed expressions as they relate stories of guilt, PTSD and persecution…’

The documentary includes a re-enactment (see still above) of what has become a signature drone strike to critics of remote warfare – the attack on a ‘convoy’ of three vehicles in Uruzgan in 2010 that I analysed in Angry Eyes (here and here); the strike was orchestrated by the crew of a Predator but carried out by two attack helicopters. Kennebeck based her reconstruction on the report from the same US military investigation I used, though I think her reading of it is limited by its focus on the Predator crew in Nevada and its neglect of what was happening (or more accurately not happening) at operations centres on the ground in Afghanistan. She’s not alone in that – follow the link to the second part of Angry Eyes above to see why – but what she adds is a series of vital interviews with the survivors:

I found the survivors of the airstrike and was the first person to interview them and get their first-person accounts… Their stories give a much larger dimension to the incident and reveal that parts of the military investigation had been sugarcoated.

Winston Cook-Wilson agrees that the cross-cutting between the strike and its victims is immensely affecting:

The most powerful section of Kennebeck’s film, by far, are the interviews with family members and witnesses of a mistaken drone attack which killed 22 men, women and children in Afghanistan. Before meeting the Afghani mother who lost her children, the man who lost his leg in the explosion, and others, Kennebeck shows the attack in re-enactment that utilizes frighteningly blurry drone vision. Slightly overdone, static-ridden voiceovers from a radio transcript are included. The emotional footage in Afghanistan here is undeniably powerful; Kennebeck then unexpectedly cuts in grainy footage, filmed by one of the families of the victims, poring over their maimed remains.

This section of the film induces nausea, grief, and confusion all at the same time.

‘Frighteningly blurry drone vision’ is exactly right, as I’ve argued elsewhere (you can find a discussion of this in the second of my ‘Reach from the Skies’ lectures and in the penultimate section of ‘Dirty Dancing’, DOWNLOADS tab). Here is Naomi Pitcairn who sharpens the same point:

We can see, clearly, how little they can actually see: tiny dots, like ants walking slowly, in single file. This is the all seeing but lacking feeling, understanding and cultural context, vision of a drone video feed and the drone operators callousness in the transcript seems to reflect that. Their bloodlust combined with the minimalism of the feed is intense in its very … primitivism.

Jeanette Catsoulis also thinks the cross-cutting between the strike and the survivors is highly effective (see also Susan Carruthers, ‘Detached Retina: The new cinema of drone warfare’, in Cineaste, who regards those sequences as providing ‘a more profound, affecting, and sustained reckoning with what drones do than anything else to date’), but she doesn’t think it sufficient:

If “National Bird” wants to persuade us that the emotional and collateral damage of this technology is greater than that caused by conventional weapons, it needs to widen its lens. Interviews with military specialists able to elucidate the complex calculus of risk and reward would have been invaluable in balancing the narrative and perhaps clarifying the ethical fuzziness.

Even so, there’s a sense that some unwritten human compact has been broken. As an ominously beautiful drone’s-eye camera glides above peaceful American streets, we’re uncomfortably reminded that an invisible death could one day hover over us all.

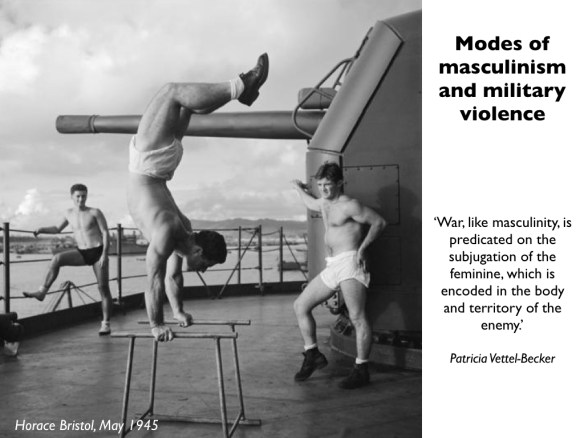

So it could – perhaps especially now. As a reminder of that dread possibility, one of the phrases that recurs in the transcript from the Uruzgan strike is ‘military-aged males’ (with all that implies), so here is an image from Tomas van Houtryve‘s photographic series Blue Sky Days. It’s also called ‘Military-Aged Males‘:

It shows civilian cadets assembling in formation at the Citadel Military College in Charleston, South Carolina.