This is the tenth in a series of extended posts on Grégoire Chamayou‘s Théorie du drone and covers the fifth and final chapter in Part II, Ethos and psyche.

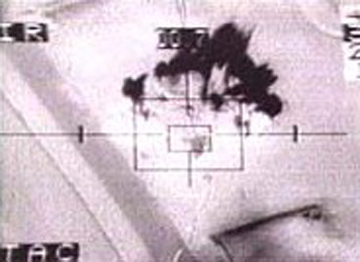

Chamayou begins with a lecture given by German artist and film-maker Harun Farocki in Karlsruhe in 2003 called ‘Phantom Images‘. A ‘phantom image’, Farocki explained, is a view that is otherwise inaccessible to a human being – like the ‘bomb’s-eye view’ that became so familiar during the Gulf War (‘a suicidal camera’). Like so many other ‘technical representations which maintain that they only represent the operative principle of a process’ these are, of course, techno-cultural performances. They are techno-cultural because they produce a constructed and constrained space – in the Gulf War images that Farocki used to frame his argument, the battle space appears empty of people, a landscape without figures, an odyssey of destruction based on an object-ontology – and they are performances because they are what Farocki called ‘operative images’ that ‘do not represent an object but are part of an operation‘ (my emphasis).

Chamayou begins with a lecture given by German artist and film-maker Harun Farocki in Karlsruhe in 2003 called ‘Phantom Images‘. A ‘phantom image’, Farocki explained, is a view that is otherwise inaccessible to a human being – like the ‘bomb’s-eye view’ that became so familiar during the Gulf War (‘a suicidal camera’). Like so many other ‘technical representations which maintain that they only represent the operative principle of a process’ these are, of course, techno-cultural performances. They are techno-cultural because they produce a constructed and constrained space – in the Gulf War images that Farocki used to frame his argument, the battle space appears empty of people, a landscape without figures, an odyssey of destruction based on an object-ontology – and they are performances because they are what Farocki called ‘operative images’ that ‘do not represent an object but are part of an operation‘ (my emphasis).

You can find more on Farocki’s fascination with the virtual/real and Immersion here and on Images of War (at a distance) here. Both ideas – immersion and distance – are central to Chamayou’s argument, but his starting-point is the idea of an operative image. He wants to think of militarized vision as a ‘sighting’ that works not only to represent an object but also to act upon it and, in the case that most concerns both of us, this is the mainspring of the production of the target.

This has a long (techno-cultural) history, but drones use a video image to fix and execute the target: ‘You can click, and when you click, you kill.’ There’s something almost magical about it, Chamayou says: a hi-tech form of voodoo violence, like sticking pins into a wax doll, in which bringing someone into view – ‘pinning’ the target in the viewfinder – transports them into the killing space.

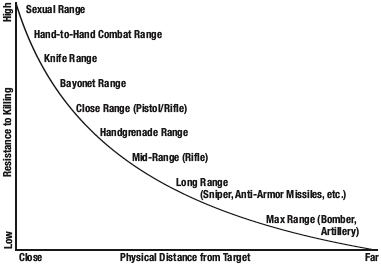

But what sort of space is it? Chamayou considers a simple diagram from Dave Grossman‘s On Killing. For readers unfamiliar with his work, here is how Grossman describes himself on the website of his Killology Research Group:

But what sort of space is it? Chamayou considers a simple diagram from Dave Grossman‘s On Killing. For readers unfamiliar with his work, here is how Grossman describes himself on the website of his Killology Research Group:

Col. Grossman is a former West Point psychology professor, Professor of Military Science, and an Army Ranger who has combined his experiences to become the founder of a new field of scientific endeavor, which has been termed “killology.” In this new field Col. Grossman has made revolutionary new contributions to our understanding of killing in war, the psychological costs of war, the root causes of the current “virus” of violent crime that is raging around the world, and the process of healing the victims of violence, in war and peace.

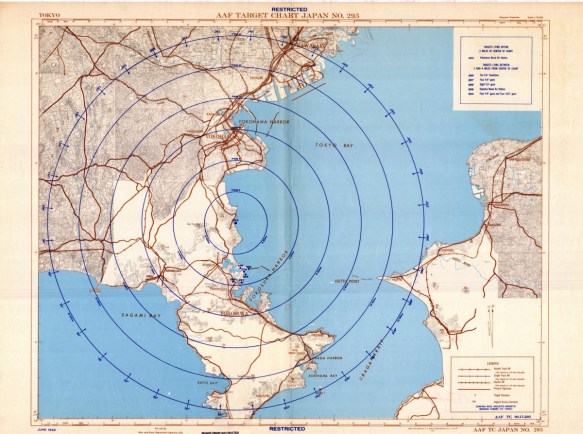

And here is the diagram, which summarises Grossman’s views on the relationship between ‘resistance to killing’ and distance from the target:

Grossman’s basic argument is that distance increases indifference and, as the annotations imply, there appears to be an historical sequence to all this. Grossman’s book was published before the advent of the drone, but – given these two axes – the Predator and the Reaper presumably ought to appear on the extreme right of the diagram, representing the radicalisation of killing at a distance.

In fact, Grossman provides a discussion of videogames in which he says that the screen acts as a barrier between the player and the violence s/he unleashes in the game, making it easier to ‘kill’: exactly the argument advanced by those who claim that drones induce a ‘Playstation mentality’ to killing.

And yet, as I’ve explained in ‘From a view to a kill’ (DOWNLOADS tab), modern videogames are profoundly immersive, and the high-resolution full motion video feeds from the drones induce such an extraordinary sense of proximity, even intimacy – remember that crews frequently claim to be 18 inches from the combat zone, the distance from eye to screen – that drones are surely also pulled towards towards the extreme left of Grossman’s diagram.

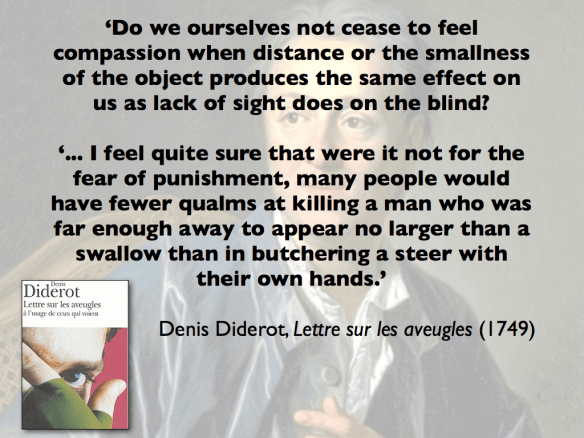

Chamayou doesn’t quote him, but Diderot’s Letter on the blind set out the original terms of the debate perfectly:

But Chamayou is quick to show that ‘distance’ is a weasel-word, and in an extended footnote he elaborates his concept of pragmatic co-presence. Co-presence denotes the possibility of A affecting B in some way, which means (in the absence of sorcery) that B must be within the sphere of action of A; more formally, co-presence involves the inclusion of one within the ‘range’ or ‘reach’ of another. This is multi-dimensional – without technical mediation you can see someone much further away than you can hear them – but in many situations technical mediations are involved and so transform the relation. This matters for two reasons.

First, there is nothing necessarily reciprocal about co-presence: what Chamayou calls ‘the structure of of co-presence’ determines what it is possible for you to do to the other, and is itself the product of struggle: each party to a conflict manouevres to produce a favourable asymmetry so that it becomes much easier for you to strike than to be hit. In this sense, all war strives to be asymmetric – it’s not confined to wars between states and non-state actors – and it’s this that in part underwrites the history of war at a distance; as William Saletan put it, effectively re-describing Grossman’s diagram,

‘Technically, this is marvelous. Look at the history of weapons development: catapult, crossbow, cannon, rifle, revolver, machine gun, tank, bazooka, bomber, helicopter, submarine, cruise missile. Every step forward consists of a physical step backward: the ability to kill your enemy with better aim at a greater distance or from a safer location. You can hit him, but he can’t hit you.’

But – Chamayou’s second rider – ‘teletechnologies’ radically transform this sequence by severing co-presence from co-localisation. What is distinctive about teletechnologies is not their capacity to act ‘at a distance’ but their indifference to and their interdigit(is)ation of ‘near’ and ‘far’.

This has far-reaching (sic) consequences because it produces a double disassociation. Where, exactly, does the action take place? Here (at Creech Air Force Base in Nevada) or there (Kandahar in Afghanistan)? There is no single answer, of course, which is precisely Chamayou’s point. This split – or series of splits, if you think of the wider networks involved – in turn engenders radically new forms of experience, of being-in-the-world, that can no longer be contained within the physico-corporeal confines of the conventional human subject.

Chamayou wants to show that this double disassociation is anything but ‘marvellous’. He accepts that the targets that are produced through the full-motion video feeds from the Predators and Reapers are much less abstract: the crews see their targets – often people, not physical objects like the buildings or missile batteries that constituted Farocki’s ’empty’ battlespace – and they see the corporeal consequences of each strike. ‘This novel combination of physical distance and visual proximity gives the lie to the old [Clausewitz-Hegelian] law of distance,’ Chamayou writes, since ‘increased distance no longer makes violence more abstract or more impersonal but, on the contrary, more graphic and more personal.’

But he insists that this proximity, even intimacy is counterbalanced by two factors which are also inscribed within the political technology of vision:

(1) ‘Proximity’ is contracted to the optical – and even this is degraded because the resolution of the video feeds reduces people to ‘avatars without faces’. I think this is less straightforward than Chamayou implies. He cites Salatan – ‘There’s no flesh on your monitor; just co-ordinates’ – which is a sharp remark, but the journalist was referring to the launch of long-range missiles (‘… tap a button on one continent and send a missile to another’) whereas the screens at Creech and elsewhere show human figures as well as co-ordinates. More significant, I think, is that when drone operators provide close air support they are also in radio and online contact with troops on the ground, and this produces a pragmatic co-presence which is considerably more ‘fleshed out’ than their otherwise purely optical encounters with others in their field of view.

(2) Drone operators can see without being seen, and Chamayou argues that ‘the fact that the killer and his victim are not inscribed in “reciprocal perceptual fields” facilitates the administration of violence’ because it ruptures what psychologist Stanley Milgram in his notorious experiments on Obedience to authority [below] called ‘the phenomenological unity of the act’. Milgram actually wrote “experienced”, not “phenomenological”, but you get the point; Milgram was discussing how much easier it is to hurt someone ‘if there is a physical separation of the act and its consequences’, which is radicalised in what the US Air Force calls the ‘remote split’ operations carried out by its Predators and Reapers.

Milgram’s thesis was a general one, but to nail the sense of disassociation to the drone Chamayou quotes Major Matt Martin, a Predator operator:

‘The suddenness of action played out at long distance on computer screens left me feeling a bit stunned… It would take some time for the reality of what happened so far away, for “real” to become real.’

Again, I think it’s more complicated than that. Martin was clearly recalling an early experience, low on the learning curve, and interviews with other drone pilots suggest that within 6 months or so most had little difficulty in apprehending the reality, even the physicality of pragmatic co-presence. The sensor operator interviewed by Omer Fast for 5,000 Feet is the Best had this to say, for example:

‘… you get more into it the longer you’re working on the Predator. Like my first fire mission. You know, we fired a Hellfire missile at the target. It didn’t quite strike [sic] me as, “Hey! I just killed someone!” My first time. It was within my first year there. It didn’t quite impact. It was like, “Yeah! I got somebody!” You know? And it was later on through a couple of more missions that I started to… The impact really dawned on me. I just ended someone’s life! That was me that did that!”‘

It’s important to remember, too, that Milgram’s work was about structures of authority, and this has a palpable effect in the case of the military chain of command which has been transformed by the networked incorporation of video feeds from the drones and the deployment of military lawyers (JAGs) on the operations floor of the Combined Air and Space Operations Center (what I called ‘oversight’ in “From a view to a kill”), which provides for a dispersion of responsibility across the network.

It’s important to remember, too, that Milgram’s work was about structures of authority, and this has a palpable effect in the case of the military chain of command which has been transformed by the networked incorporation of video feeds from the drones and the deployment of military lawyers (JAGs) on the operations floor of the Combined Air and Space Operations Center (what I called ‘oversight’ in “From a view to a kill”), which provides for a dispersion of responsibility across the network.

Equally important, I suspect, is that fact that drone crews are not only ‘following orders’, as the familiar jibe has it: they are also following procedures that transform military violence into a process that is at once techno-scientific and quasi-juridical and thus seen as conducted under the sign of an unimpeachable (military) Reason.

Joseph Pugliese makes a parallel argument about the incorporation of military-legal discourse into the techno-logic of the targeting process:

‘I argue that the parenthetical relation of law to technology is premised on a topical hiatus that disassociates the executioner who manipulates the killing technology of the drone from the facticity of the resultant execution. In this scenario, law is conceived of in the most radically instrumental of understandings: it enables and legitimates the execution while simultaneously suspending the connection between the doer and the deed.’

And yet at the same time, Pugliese explains, there is a ‘prosthetic’ relation between law and technology, in which ‘the human agent is always already inscribed by the technics of law.’ From the very beginning, he insists, the body is always already ‘instrumentalised by a series of technologies’ and also inscribed, from the very beginning, by a series of laws. In short, ‘law is always already inscribed on the body, precisely as techné from the very first. This process of prosthetic inscription operates to constitute the very conditions of possibility for the conceptual marking of the body as”‘human’”‘: ‘The prosthesis,’ notes Bernard Stiegler, ‘is not a mere extension of the human body; it is the constitution of this body qua “human”’.’

And yet at the same time, Pugliese explains, there is a ‘prosthetic’ relation between law and technology, in which ‘the human agent is always already inscribed by the technics of law.’ From the very beginning, he insists, the body is always already ‘instrumentalised by a series of technologies’ and also inscribed, from the very beginning, by a series of laws. In short, ‘law is always already inscribed on the body, precisely as techné from the very first. This process of prosthetic inscription operates to constitute the very conditions of possibility for the conceptual marking of the body as”‘human’”‘: ‘The prosthesis,’ notes Bernard Stiegler, ‘is not a mere extension of the human body; it is the constitution of this body qua “human”’.’

Still, Chamayou suggests that (1) and (2) work together to sustain what Mary Cummings calls ‘moral buffering’. In other words, and in counterpoint to optical proximity, the dispositif also provides a powerful means of distanciation. Here is Fast’s interviewee again:

‘There’s always more of a personal touch when you’re watching something live. And it’s even more personal when you’re the one that did it… Well, I mean you get more – I guess – emotionally distant. As time goes on. But I mean… I guess in my case, and some of the cases of the guys that I knew, as more time went by you put yourself more and more in the position that this is more and more real life and that you are actually there… And after a while you become emotionally distant. But still you put yourself more and more as if you’re standing right there…’

This is compounded, so Chamayou argues, by a different dimension of ‘remote split’ operations. Because Predators and Reapers can stay aloft for 18 hours or more (the ‘persistent presence’ that makes them so much in demand), their crews work shifts and commute each day (or night) between home and work or, more accurately, between peace and war. One drone operator saw this as a peculiarly strung-out existence: ‘We were just permanently between war and peace’ (my emphasis). Matt Martin said much the same. US-based crews ‘commute to work in rush-hour traffic, slip into a seat in front of a bank of computers, fly a warplane to shoot missiles at an enemy thousands of miles away, and then pick up the kids from school or a gallon of milk at the grocery store on [their] way home for dinner.’ He described it as living ‘a schizophrenic existence between two worlds’; the sign at the entrance to Creech Air Force Base read ‘You are now entering CENTCOM AOR [Area of Operations]’, but ‘it could just as easily have read “You are now entering C.S. Lewis’s Narnia” for all that my two worlds intersected.’

This is compounded, so Chamayou argues, by a different dimension of ‘remote split’ operations. Because Predators and Reapers can stay aloft for 18 hours or more (the ‘persistent presence’ that makes them so much in demand), their crews work shifts and commute each day (or night) between home and work or, more accurately, between peace and war. One drone operator saw this as a peculiarly strung-out existence: ‘We were just permanently between war and peace’ (my emphasis). Matt Martin said much the same. US-based crews ‘commute to work in rush-hour traffic, slip into a seat in front of a bank of computers, fly a warplane to shoot missiles at an enemy thousands of miles away, and then pick up the kids from school or a gallon of milk at the grocery store on [their] way home for dinner.’ He described it as living ‘a schizophrenic existence between two worlds’; the sign at the entrance to Creech Air Force Base read ‘You are now entering CENTCOM AOR [Area of Operations]’, but ‘it could just as easily have read “You are now entering C.S. Lewis’s Narnia” for all that my two worlds intersected.’

The way crews survive, Chamayou suggests, is by partitioning, ‘setting aside’, but this is extremely difficult for commuter-warriors as they regularly and rapidly move between a domestic sphere in which killing is taboo and a military sphere where (so he says) it is ‘a virtue’. The superimposition of these two worlds – their contradictory clash – means that crews are in a sense ‘both in the rear and at the front, living in two very different moral universes between which their lives are torn.’

This is precisely the situation dramatised in George Brant‘s play Grounded, which I noted in an earlier post, and Chamayou cites a former USAF sensor operator Brandon Bryant (whose testimony I discussed here) to the same effect. In both cases, crew members plainly are affected, even distressed by what they see on the screen; in fact Bryant has bee diagnosed with PTSD.

But Chamayou insists that this sort of testimony is rare and that most of them do manage to compartmentalise. Fast’s sensor operator:

‘A lot of us learn real fast to leave all of our problems at the door. You know, when we’re leaving the squadron and heading home. Just kind of putting it on a rack and pushing it out of your mind.’

And this, Chamayou concludes, nails the real psychopathology of the drone. He calls French philosopher Simone Weil’s Gravity and grace to his aid:

‘The faculty of setting things aside opens the door to every sort of crime… The ring of Gyges who has become invisible – this is precisely the act of setting aside: setting oneself aside from the crime one commits; not establishing the connection between the two.’

Chamayou has used the myth of Gyges earlier in his critique, but here he invokes Weil to claim that the psychopathology of the drone is not the trauma some say that drone crews experience ‘but on the contrary the industrial production of compartmentalised psyches, protected from all possibility of reflection on the violence they have committed, just as their bodies are already protected against every possibility of exposure to the enemy.’

I’m really not sure about this. ‘Protected from all possibility of reflection’? Much of the evidence that Chamayou cites here – like Milgram’s experiments – could be applied to most forms of military violence. Here, for example, is Arnold Bennett describing artillery at work in Over there: war scenes on the Western Front (1915):

I’m really not sure about this. ‘Protected from all possibility of reflection’? Much of the evidence that Chamayou cites here – like Milgram’s experiments – could be applied to most forms of military violence. Here, for example, is Arnold Bennett describing artillery at work in Over there: war scenes on the Western Front (1915):

‘The affair is not like shooting at anything. A polished missile is shoved into the gun. A horrid bang – the missile has disappeared, has simply gone. Where it has gone, what it has done, nobody in the hut seems to care. There is a telephone close by, but only numbers and formulae – and perhaps an occasional rebuke – come out of the telephone, in response to which the perspiring men make minute adjustments in the gun or in the next missile.

‘Of the target I am absolutely ignorant, and so are the perspiring men.’

I’ve found the same sentiments expressed by bomber crews during the Second World War. The difference, clearly, is that drone strikes involve far more than ‘numbers and formulae’ – co-ordinates on the screen – and that the visual production and so-called ‘prosecution’ of the target takes place in near real time, in vivid detail and under the eye of military lawyers. But it is not surprising (nor, I think, especially pathological) that those who carry out these strikes conduct themselves with a certain seriousness, a ‘professionalism’ if you like, that precludes emotional investment. This is from David Wood‘s interview with a highly experienced USAF drone pilot:

Q: You must develop an emotional tie with the people on the ground that makes it hard if there is going to be a strike or a raid, people are going to be killed.

A: I would couch it not in terms of an emotional connection, but a … seriousness. I have watched this individual, and regardless of how many children he has, no matter how close his wife is, no matter what they do, that individual fired at Americans or coalition forces, or planted an IED — did something that met the rules of engagement and the laws of armed conflict, and I am tasked to strike that individual.

‘Professionalism’ shouldn’t be used as a mask to hide from critique, to be sure. These crews are trained to perform with a calculative reason, dispassionately, through a techno-cultural and techno-legal armature, so that, as one USAF major told Nicola Abé, when she was preparing for a strike ‘there was no time for feelings’. Or again, from another pilot operating a Predator over Afghanistan:

‘We understand that the lives we see in the screens are as real as our own… I would not compare what I do as a job comparable to Call of Duty/any other video game, in any sense. It is very real and the seriousness of the lives on the ground is very real and instilled in all of our training. It is never something that we joke about. Very serious business.’

As I’ve noted before, there are (too) many instances in which crews do joke about their missions, the sort of ‘gallows humour’ that is no doubt a common reaction to hunter-killer missions: but isn’t this also likely to be common amongst all military professionals who are trained to kill? One pilot explicitly rejected the suggestion that drone crews become disassociated from what they do:

‘I wonder why people think this. We understand what we are doing is real world operations. We know our actions have consequences. I don’t understand the idea of being desensitized due to some operators not being in an actual firefight/combat zone.’

Later in the online exchange, the same pilot insists: ‘It’s very real. Some of the stuff I’ve seen is burned into my brain’ – and then Brandon Bryant joins the conversation to ‘agree with what you guys have said.’ He’s on record as writing in his personal combat diary ‘I wish my eyes would rot.’

I realise that these passages can’t settle matters, but they surely cast doubt on the implication that drone crews are as machinic as the aircraft they fly. Pugliese insists that the drone ‘cannot be reduced to a mindless machine of purely robotic acts’; neither, by virtue of what Pugliese calls their prosthetic relation to the drone, can the crew who fly them. I still think that one of the most salient differences introduced by drones is the differential distanciation they allow when they provide close air support: an unprecedentedly close relation with troops on the ground and a calculative detachment from others in their field of view.

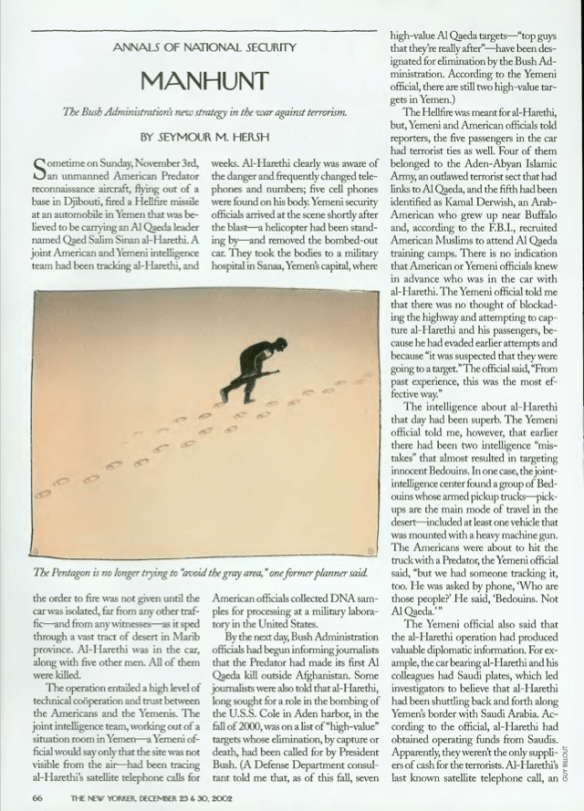

I realise, too, that this can’t apply to targeted killings, and so I leave you with this statement by Lt General Michael DeLong, who as deputy commander of US Central Command had to sign off on the first CIA-directed targeted killing, in Yemen in November 2002. Then CIA Director George Tenet called DeLong to ask him to give the order, since the Predator was flown by a USAF crew:

‘Tenet calls and said, “We got the target.” … I called General Franks [commander of CENTCOM]. Franks said, “Hey, if Tenet said it’s good, it’s good.” I said, “Okay … I’m going down to the UAV room.” … We had our lawyer there. Everything was done right. I mean, there was no hot dog. … The rules of war, the rules of combat that we had already set up, the rules of engagement ahead of time. Went by them. Okay, it’s a good target. …

I’m sitting back … looking at the wall, and I’m talking to George Tenet. And he goes, “You got to make the call?” These Predators had been lent to him, but the weapons on board were ours. So I said, “Okay, we’ll make the call. Shoot them.”

Everything may have been ‘done right’, the procedures followed, but when DeLong was asked ‘What does it feel like when you know you’re going down there to kill somebody?’ He replied:

‘It’s just war. It’s no different than going to the store to buy some eggs; it’s just something you got to do.’

And, as Chamayou would surely insist, it wasn’t war. It was, as Seymour Hersh wrote in the New Yorker on 23 December 2002, a manhunt.

To be continued.