When I wrote ‘Seeing Red: Baghdad and the event-ful city’ (DOWNLOADS tab) I was intrigued by the way in which the US military apprehended the city as a field of events:

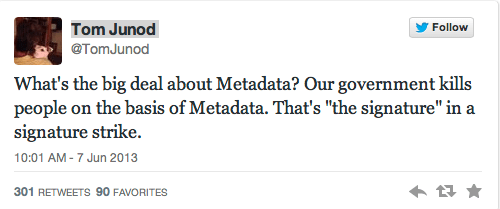

‘In Baghdad, these security practices performed a continuous audit that compiled reports of events (Significant Activity Reports or SIGACTS) and correlated the incidence of ‘enemy-initiated attacks’ and other ‘enemy actions’ with a series of civil, commercial and environmental indicators of the population at large: moments in the production of what Dillon and Lobo-Guerrero call a generalized bio-economy.’

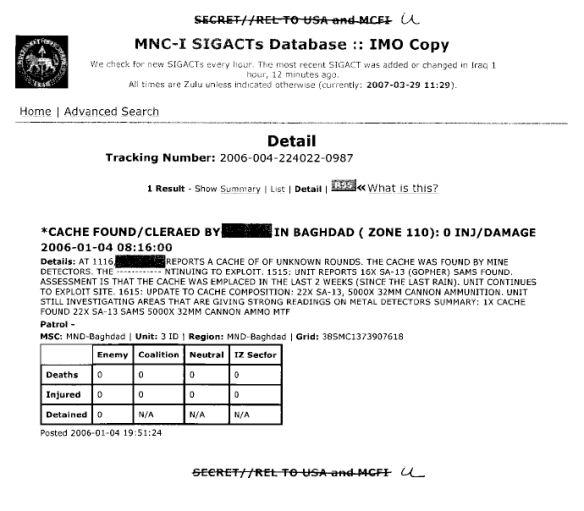

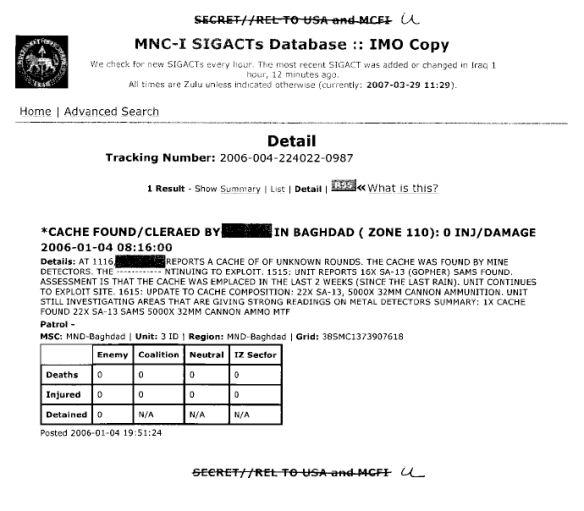

The animating core of the system was the SIGACT – shown below – and these were eventually fed into a single reporting and analysis platform, the Combined Information Data Network Exchange (CIDNE).

‘The primary transcription of an event, its constitution as a SIGACT, with all its uncertainties and limitations, was transmitted downstream to be digitized and visualized, correlated and ‘cleansed’, so that it could be aggregated to show trends or mapped to show distributions. All the systems for SIGACT recording and analysis interfaced with visualization and presentation software, which was used to generate ‘storyboards’ at every level in the chain.’

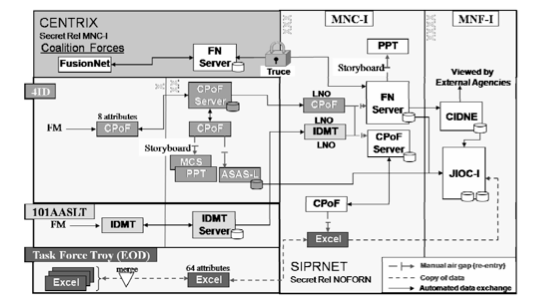

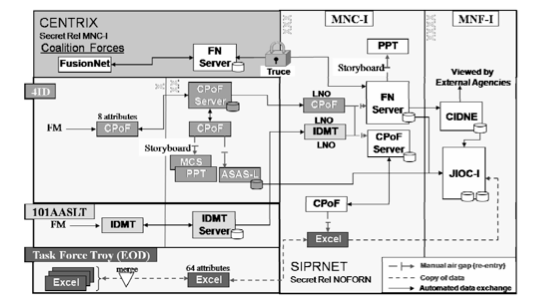

The chain as it was constituted in Iraq in May 2006 is shown below; CENTRIX (top left) is the Combined Enterprise Regional Information Exchange System that provided information exchange across the US-led coalition; CPoF (scattered across the centre field) is the Command Post of the Future, a distributed GIS system I discussed in the original essay that provided a command-level visualization of the battlespace as a field of events (a system that has since been upgraded multiple times); and at the centre right you can see the key automated data exchanges to and from CIDNE:

Since I wrote, scholars have used SIGACT reports much more systematically to analyse the connective tissue between ethno-sectarian violence and the ‘surge’ – see, for example, Stephen Biddle, Jeffrey Friedman and Jacob Shapiro, ‘Testing the surge’, International Security 37 (1) (2012) 7-40; Nils Weidmann and Idean Saleyhan, ‘Violence and ethnic segregation: a computational model applied to Baghdad‘, International Studies Quarterly 57 (2013) 52-64 – to explore the political dynamics of civilian casualties – see, for example, Luke Condra and Jacob Shapiro, ‘Who takes the blame? The strategic effects of collateral damage’, American Journal of Political Science 56 (1) (2012) 167-87 – and to conduct more general evaluations of counterinsurgency in Iraq: see, for example, Eli Berman, Jacob Shapiro and Joseph Felter, ‘Can hearts and minds be bought? The economics of counterinsurgency in Iraq’, Journal of political economy 119 (4) (2011) 766-819.

I’ve been revisiting these modelling exercises for The everywhere war, because they require me to rework my essay on ‘The biopolitics of Baghdad’ (though not, I think, to change its main argument). I’m struck by the idiom they use – my critique of spatial science written in another age would have been substantially different had it been less preoccupied with the detecting of spatial pattern, had its methods been applied more often to issues that matter, and had its architects been less convinced of the self-sufficiency of their methods.

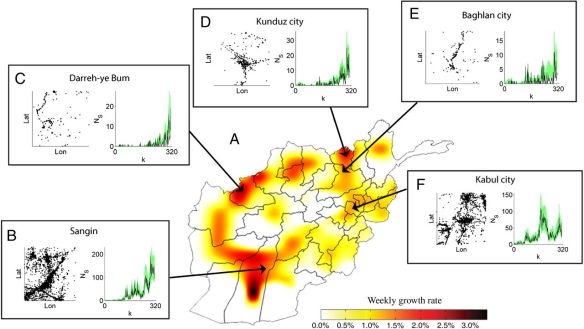

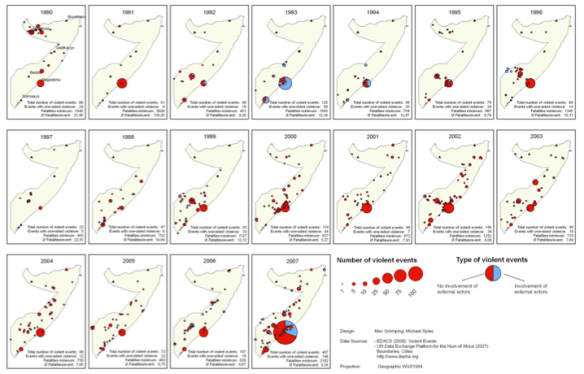

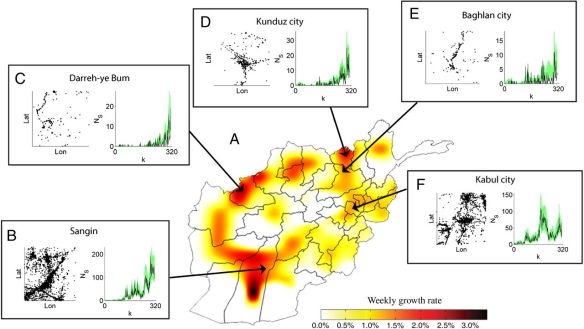

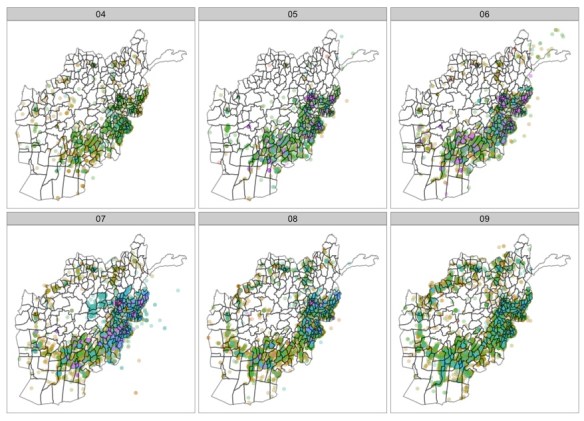

But I’m also struck by the idiom of the SIGACT itself. We’ve since become much more accustomed to its staccato rhythm through Wikileaks’ release of the Afghan and Iraq War Diaries, whose key source was CIDNE. Again, these have been visualised and analysed in all sorts of ways: see, for example, here, here, here and here (and especially Visualizing Data and its links here). The image below comes from Andrew Zammit-Mangion, Michael Dewar, Visakan Kadirkamanathan and Guido Sanguinetti,’Point-process modelling of the Afghan War Diaries’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109 (31) (2012) and shows the time-space incidence of events recorded in the Diaries (here I suspect I’m channelling half-remembered conversations with Andrew Cliff….)

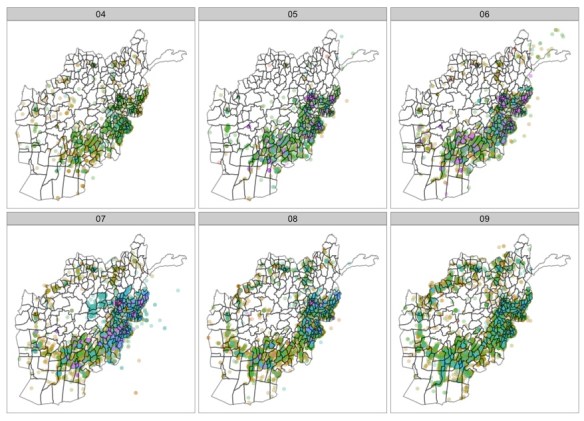

And here, rather more prosaically, is another version – by Drew Conway and Mike Dewar – that provides a time-sequence of the mounting intensity of the war 2004-2009 (for Danger Room‘s discussion and gloss, see here):

Now David Pinder has kindly drawn my attention to an extraordinarily suggestive essay by Graham Harwood, ‘Endless War: on the database structure of armed conflict’ over at rhizome, and to the art-work that is it subject, which together have returned me to my original interest in the ‘event-field’ of later modern war and the automated interactions between its data platforms.

Graham’s central question is deceptively simple: ‘How does the way war is thought relate to how it is fought?’ SIGACTS populate the digital battlespace with events and invite a calculative and algorithmic apprehension of the field of military violence. To show what this means, Graham and his partner Matsuko Yokokoji (who together compose YoHa: English translation ‘aftermath’) joined with his Goldsmith’s colleague Matthew Fuller to produce an intriguing artwork, Endless War.

It processes the WikiLeaks Afghan War Diary data set as a collection of analytic viewpoints, both machine and human. A software-driven system, Endless War reveals the structure of these viewpoints by using N-gram fingerprints, a method that allows sorting of the text as an anonymous corpus without having to impose predetermined categories on it. Presented as a gallery installation, the system includes a computer that processes the data in real time, projections of the results, and coil pick-up microphones on the central processing unit that sonify the inner working of the machine.

The torrent files released by WikiLeaks in 2010 are the residue of the system that created them, both machine and human. They seem to hint at the existence of a sensorium, an entire sensory and intellectual apparatus of the military body readied for battle, an apparatus through which the Afghan war is both thought and fought.

You can get a sense of the result from vimeo’s record of the installation at the Void Gallery in Derry:

This is a video, obviously, but Endless War isn’t a video. As the artists explain in a note added to the vimeo clip:

Just as an algorithm is an ‘effective procedure’, a series of logical steps required to complete a task, the Afghan War Diary shows war as it is computed, reduced to an endless permutation of jargon, acronyms, procedure recorded, cross-referenced and seen as a sequence or pattern of events.

Endless War is not a video installation but a month-long real-time processing of this data seen from a series of different analytical points of view. (From the point of view of each individual entry; in terms of phrase matching between entries; and searches for the frequency of terms.) As the war is fought it produces entries in databases that are in turn analysed by software looking for repeated patterns of events, spatial information, kinds of actors, timings and other factors. Endless War shows how the way war is thought relates to the way it is fought. Both are seen as, potentially endless, computational processes. The algorithmic imaginary of contemporary power meshes with the drawn out failure of imperial adventure.

This computational assemblage (think not only of the cascading algorithms but also of the people and the handshakes between the machines: a political technology ‘full of hungry operators’, as Graham has it) is performative: it is at once an inventory – an archive – and a machine for producing a particular version of the military future. Graham again:

‘A SigAct necessarily retains evidential power that reflects its origin outside of the system that will now preserve it, but once isolated from blood and guts, sweat and secretions of the theatre of action (TOA), the SigActs are reassembled through a process of data atomisation. This filter constructs a domain where the formal relation, set theory, and predicate logic has priority over the semantic descriptions of death, missile strikes, or the changing of a tank track and the nuts and bolts needed…

This system of record keeping can be seen as a utopia of war. It is idealized, abstracted, contained; time can be rolled back or forward at a keystroke, vast distances traversed in a query, a Foucauldian placeless place that opens itself up behind the surface of blood-letting and hardware maintenance and the ordering of toilet rolls. A residue that casts a shadow to give NATO visibility to itself. As the ensemble of technical objects and flesh congeal, they create an organ to collectively act to rid itself of some perceived threat—this time from Al Qaeda or the Taliban—faulty vehicles, bad supplies, or invasive politics. This organ also allows NATO’s human souls to imagine themselves grasping the moment, the contingency of now. All of the war, all of the significant events, all of the time, all of the land, coming under the symbolic control of a central administration through the database, affording governance to coerce down the chain of command.’

This is a much more powerful way of capturing – and, through the physical installation itself, conveying – what I originally and imperfectly argued in ‘Seeing Red’:

‘… optical detachment is threatened by a battle space that is visibly and viscerally alive with death; biopolitics bleeds into necropolitics. And yet the Press Briefings that are parasitic upon these visualizations move in a dialectical spiral, and their carefully orchestrated parade of maps, screens and decks reinstates optical detachment. For even as the distancing apparatus of the world-as-exhibition is dissolved and the map becomes the city, so the city becomes the map: and in that moment – in that movement – Baghdad is transformed into an abstract geometry of points and areas and returned to the field of geopolitics. And as those maps are animated, the body politic is scanned, and the tumours visibly shrink, so Baghdad is transformed into a biopolitical field whose ‘death-producing activities [are hidden] under the rhetoric of making live’ (Dauphinee and Masters 2007: xii). In this looking-glass world bodies are counted but they do not count; they become the signs of a pathological condition and the vector of recovery. These processes of abstraction are, of course, profoundly embodied. This is not algorithmic war, and behind every mark on the map/city is a constellation of fear and terror, pain and grief. For that very reason our disclosure of the infrastructure of insight cannot be limited to the nomination of the visible.’

In a series of posts on photography Trevor Paglen provides some ideas that intersect with my own work on Militarized Vision and ‘seeing like a military’. First, riffing off Paul Virilio, Trevor develops the idea of photography as a ‘seeing machine‘:

In a series of posts on photography Trevor Paglen provides some ideas that intersect with my own work on Militarized Vision and ‘seeing like a military’. First, riffing off Paul Virilio, Trevor develops the idea of photography as a ‘seeing machine‘: