There is a telling anecdote in Lyn Macdonald‘s account of The Somme:

Climbing on to the firestep, the Staff Captain cautiously raised his head above the parapet and looked across. ‘Good God!’ he exclaimed. ‘I didn’t know we were using Colonial troops!’ Pretor-Pinney made no reply. Hoyles and Monckton exchanged grim looks. ‘Dear God,’ muttered Monckton, when the Colonel and the visitor had moved away to a safe distance, ‘has the bastard never seen a dead man before?’ It was a rhetorical question. Lying out in the burning sun, soaked by the frequent showers of a week’s changeable weather, the bodies of the dead soldiers had been turned black by the elements. The Battalion spent the rest of the day burying them.

In fact, it’s doubly revealing. On one side, it confirms the (I think simplistic) stereotype of the General Staff and their distance from death; but on the other side it also speaks to what Santanu Das, writing in the Guardian, calls ‘the colour of memory’:

In 1914, Britain and France had the two largest empires, spread across Asia and Africa, and an imperial war necessarily became a world war.

More than 4 million non-white men were recruited into the armies of Europe and the US. In a grotesque reversal of Joseph Conrad’s vision, thousands of Asians, Africans and Pacific Islanders were voyaging to the heart of whiteness and far beyond – to Mesopotamia, East Africa, Gallipoli, Persia and Palestine. Two million Africans served as soldiers or labourers; a further 1.3 million came from the British “white” dominions. The first shot in the war was fired in Togoland, and even after 11 November 1918 the war continued in East Africa.

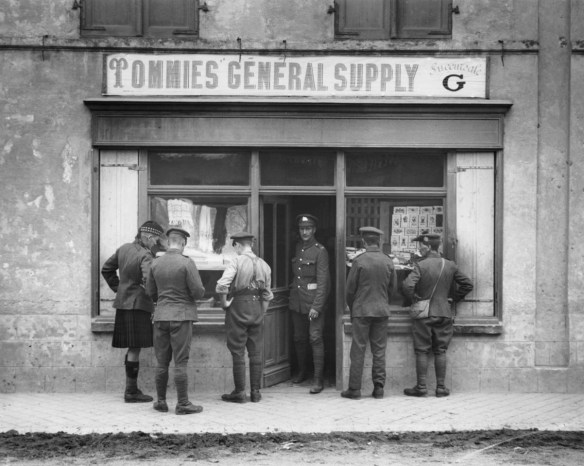

A South African labourer said he went to war to “see different races”. If one visited wartime Ypres, one would have seen Indian sepoys, tirailleur Senegalese, Maori Pioneer battalions, Vietnamese troops and Chinese workers.

Today, one of the main stumbling blocks to a truly global and non-Eurocentric archive of the war is that many of these 1 million Indians, or 140,000 Chinese, or 166,000 West Africans, did not leave behind diaries and memoirs. In India, Senegal or Vietnam there is nothing like the Imperial War Museum; when a returned soldier or village headman died, a whole library vanished.

Moreover, as the former colonies became nation states, nationalist narratives replaced imperial war memories. Stories that did not fit were airbrushed. In Europe, communities turned to their own dead and damaged.

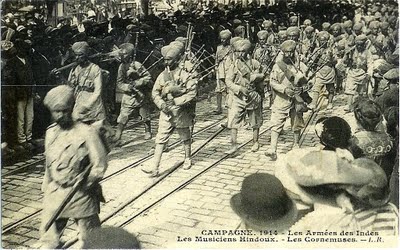

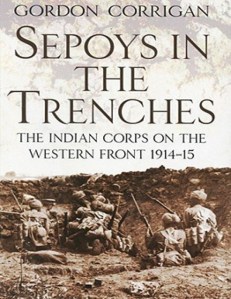

In ‘Gabriel’s Map’ I began in East Africa in 1914 with an Indian Army contingent – whose staff officers included, in William Boyd‘s An Ice-Cream War, the young Gabriel Cobb – sent to seize German East Africa defended by the local Schutztruppen under German command. But as I travelled back to the Western Front the colonial troops who also served there slipped from the record. Yet by the end of September 1914 two Indian divisions and a cavalry brigade had already arrived in France (see above), and in October the first sepoys were sent into battle at Ypres. If British, French and German troops were shocked at the devastation of a European countryside that was, in its essentials, once familiar to them, what could the freezing cold, the endless mud and the splintered trees have meant to these men (who usually arrived unprepared and ill-equipped for the winter)?

I suspect a satisfying answer has to wait for Santanu’s next book, India, Empire and the First World War: words, images and objects (Cambridge University Press, 2015). But in the meantime the whitening of the Western Front (and other theatres of the War) can be resisted through other sources. Some of them are listed in his brief essay on ‘The Indian sepoy in the First World War’ for the the British Library (and you can find ‘Experiences of colonial troops’, adapted from his Introduction to Race, empire and First World War writing [Cambridge University Press, 2011] here).

I suspect a satisfying answer has to wait for Santanu’s next book, India, Empire and the First World War: words, images and objects (Cambridge University Press, 2015). But in the meantime the whitening of the Western Front (and other theatres of the War) can be resisted through other sources. Some of them are listed in his brief essay on ‘The Indian sepoy in the First World War’ for the the British Library (and you can find ‘Experiences of colonial troops’, adapted from his Introduction to Race, empire and First World War writing [Cambridge University Press, 2011] here).

In addition Christian Koller‘s ‘The recruitment of colonial troops in Africa and Asia and their deployment in Europe during the First World War’, Imigrants & Minorities 26 (1/2) (2008) 111-133 [open access pdf here] provides a helpful context and more references (including French and German sources), and Gajendra Singh‘s The testimonies of Indian soldiers and the two world wars: between self and sepoy (Bloomsbury, 2014) is a wider, though inevitably selective account of the fabrication of Indian military identities under the Ra (the chapter on ‘Throwing snowballs in France’ is also available in Modern Asian Studies 48 (4) (2014): it’s an artful discussion of the (mis)fortunes of a chain letter – this is the ‘snowball’ in question – that ran foul of the military censor). The Round Table 103 (2) (2014) is a special issue devoted to ‘The First World War and the Empire-Commonwealth’.

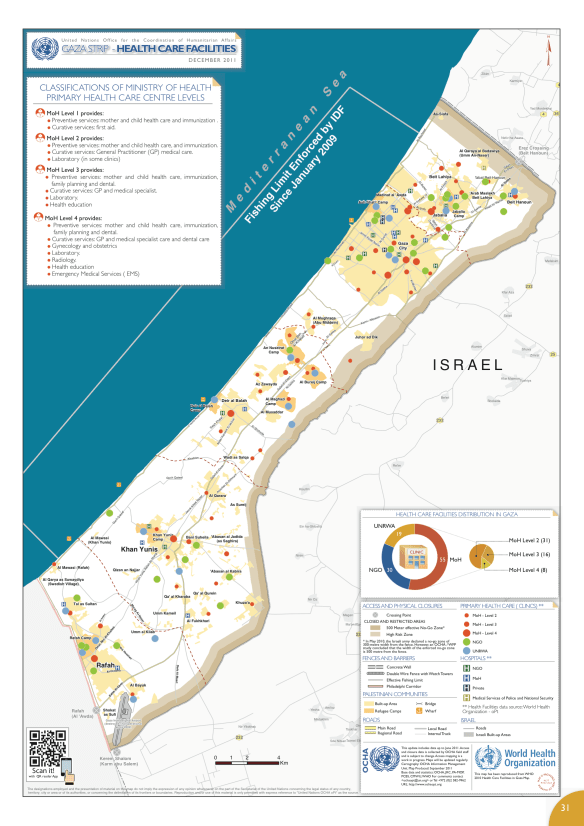

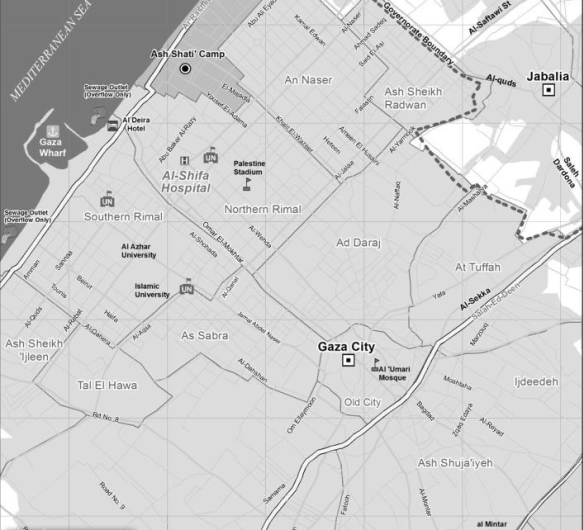

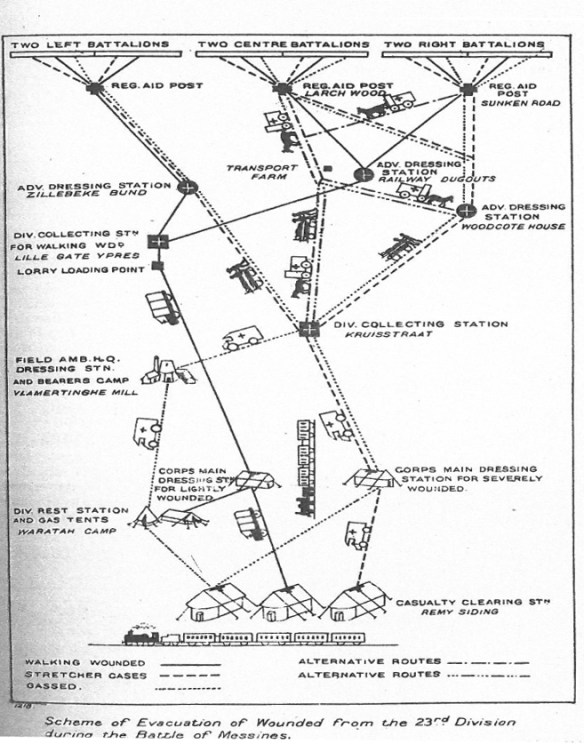

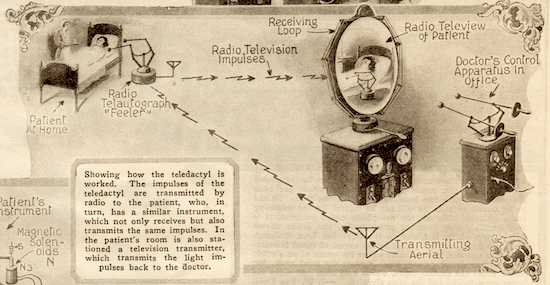

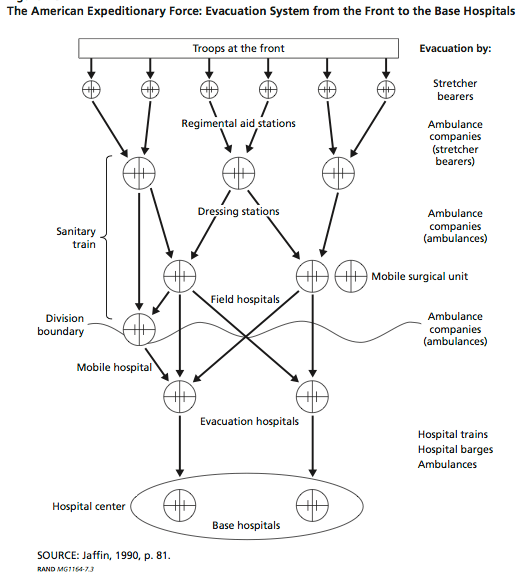

Finally, I’m working my way through Andrew Tait Jarboe‘s excellent PhD thesis, Soldiers of empire: Indian sepoys in and beyond the metropole during the First World War, 1914-1919 (Northeastern, 2013): during my current research on military-medical machines 1914-2014 I’ve found a number of references to the treatment of wounded Indian troops on the Western Front – their evacuation on hospital trains and their treatment in segregated hospitals – and Andrew’s third chapter (‘Hospital’) provides an illuminating reading of what was happening:

‘Between 1914-18, the British established segregated hospitals for wounded Indian soldiers in France and England… [T]hese hospitals were not benign institutions of healing. Like hospitals that repaired the bodies of English soldiers, Indian hospitals played a crucial role in sustaining the war-making capacity of the British Empire. Indian hospitals in Marseilles or Brighton also served an imperial purpose. As sites of propaganda, they reaffirmed the ideologies of imperial rule for audiences at home, abroad, and within the hospital wards. Yet even while the British Empire succeeded to a considerable extent in exploiting the manpower of India, … wounded sepoys were rarely ever mere pawns on the imperial chessboard. Hospital authorities were committed to two policies: returning sepoys to the front, and protecting white prestige. Wounded sepoys found ways of resisting both. In this way, Indian hospitals readily became what British authorities hoped they would not: spaces where imperial subalterns contested the policies and ideologies of imperial rule.’

For imagery of non-European troops on the Western front and elsewhere, try this page at the Black Presence in Britain. More wide-ranging is the exhibition organised by the Alliance française de Dhaka, War and the colonies 1914-1918, that you can visit online here (I’ve taken the image above from that collection).

All of this, clearly, adds another dimension to Patrick Porter‘s lively discussion of Military Orientalism: Eastern war through Western eyes (2009). But it’s not only an opportunity to reverse (and re-work) that subtitle. The Times of India reports a campaign to change ‘the colour of memory’ by instituting 15 August as a Remembrance Day in India:

“This will be our Remembrance Day. We have attended such memorial functions in France where heads of different states converge and the civilian turnout is quite big. But we don’t see a single Indian face there—quite an irony, given the fact that 1, 40,000 Indians defended French soil from German aggression in the Great War, and many never returned home. That’s why we, NRIs from France, came up with this project,” says a representative of Global Organization for People of Indian Origin (GOPIO), France.