When Eyal Weizman was in Vancouver last March – joining us for Gaston Gordillo‘s workshop on Space, materiality and violence at the Peter Wall Institute for Advanced Studies – he delivered a public lecture on The Conflict Shoreline: Colonialism as Climate Change.

It’s now available as an extended essay (96 pp) from Steidl in association with Cabinet Books:

The village of al-‘Araqib has been destroyed and rebuilt more than seventy times in the “battle over the Negev,” an ongoing Israeli state campaign to uproot the Bedouins from the northern threshold of the desert. Unlike other frontiers fought over during the Israel–Palestine conflict, however, this threshold is not demarcated by fences and walls but advances and recedes in response to cultivation, colonization, displacement, urbanization, and climate change.

The fate of al-‘Araqib, like that of other Bedouin villages along the desert’s threshold, its “aridity line,” is bound up with deep environmental changes. But whereas even the most committed environmentalists today conceive of climate change as an accidental and unintentional side effect of modernity, Israeli architect and theorist Eyal Weizman argues that from the point of view of colonial history, climate change has never been simply collateral damage. It has always been a stated goal; “making the desert bloom” is, in effect, “changing the climate.”

In examining this history, Weizman outlines attempts—from the Ottoman era through the period of European colonization to the present—to scientifically define, measure, and map the threshold of the desert. Such efforts have been important because imperial and, later, national governments—whose laws have never recognized property rights in the desert—aimed to push back this threshold as they tried to expand the limits of arable land and bring the nomads under state control. In the Negev, the displacement of the weather and the displacement of the Bedouins have gone hand in hand. But while the desert edge, and the Bedouins, have been driven further and further south, global climate change today acts as a major counterforce. Predictably, the Bedouins are caught in the middle.

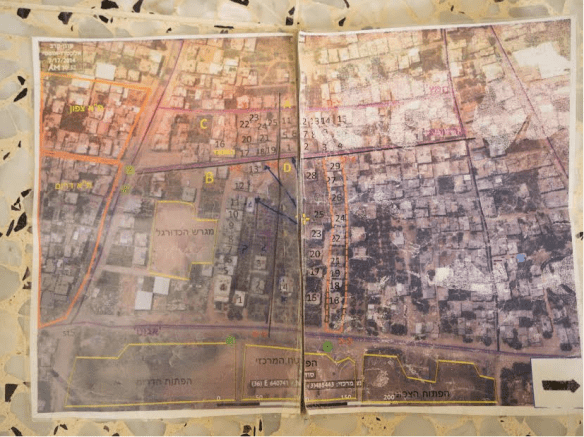

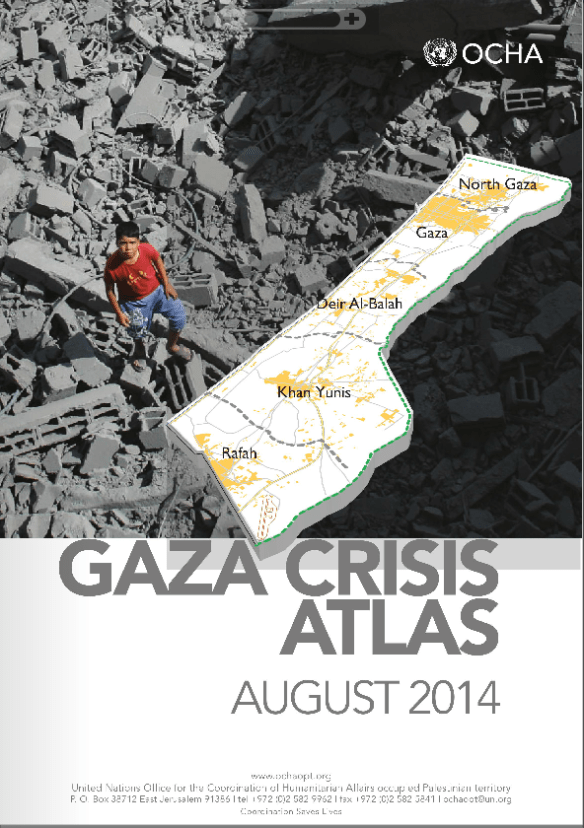

Brilliantly researched and argued, Weizman’s text—part detective story, part history lesson, and part scientific analysis—explores the changing threshold of the Negev through the extraordinary contemporary photographs of American artist Fazal Sheikh, as well as an array of documents, maps, and images, including historical aerial imagery, remote sensing data, state plans, court testimonies, and nineteenth-century travelers’ accounts. Together, these disparate forms of evidence establish the “conflict shoreline” as a border along which climate change and political contestation are deeply, perilously entangled.

You can find some of the background, and the relation to Eyal’s Forensic Architecture project, in an interview earlier this year:

I’m mostly trying to establish forensic architecture as a critical field of practice and as an agency that produce and disseminate evidence about war crimes in urban context. Recent forensic investigations in Guatemala and in the Israeli Negev involved the intersection of violence and environmental transformations, even climate change. For trials and truth commissions, we analyze the extent to which environmental transformation intersect with conflict.

The imaging of this previously invisible types of violence—‘environmental violence’ such as land degradation, the destruction of fields and forests (in the tropics), pollution and water diversion, and also long term processes of desertification—we use as new type of evidence of processes dispersed across time and space. There are other conflicts that unfold in relation to climatic and environmental transformations and in particular in relation to environmental scarcity.

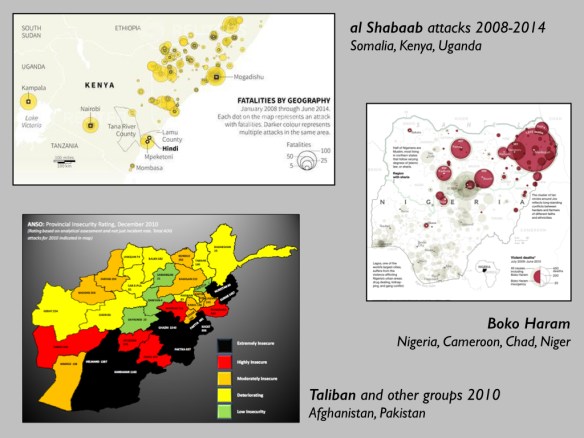

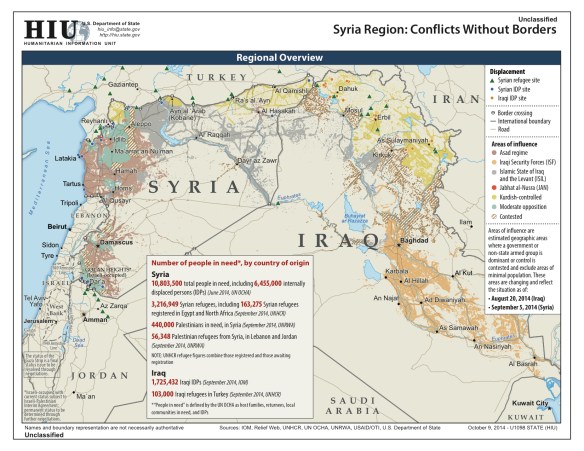

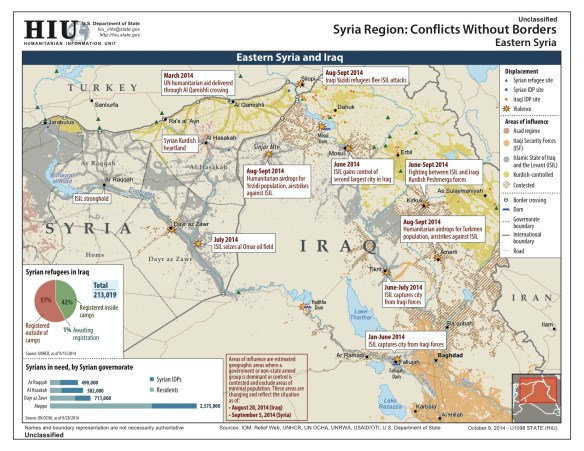

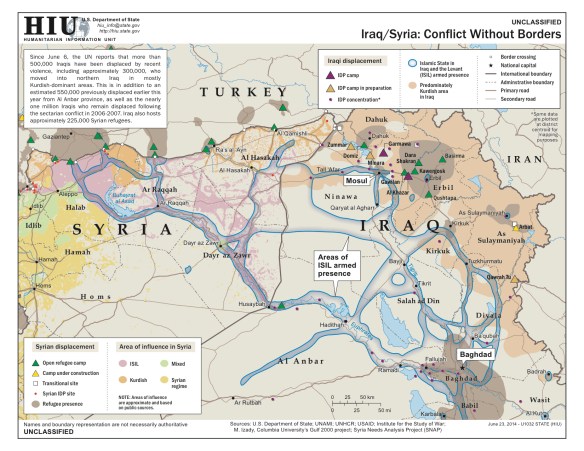

Conflict has reciprocal interaction with environment transformation: environmental change could aggravate conflict, while conflict tends to generate further environmental damage. This has been apparent in Darfur, Sudan where the conflict was aggravated by increased competition over arable due to local land erosion and desertification. War and insurgency have occurred along Sahel—Arabic for ‘shoreline’—on the southern threshold of the Sahara Desert, which is only ebbing as million of hectares of former arable land turn to desert. In past decades, conflicts have broken out in most countries from East to West Africa, along this shoreline: Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia, Sudan, Chad, Niger, Mali, Mauritania, and Senegal. In 2011 in the city of Daraa, farmers’ protests, borne out of an extended cycle of droughts, marked the beginning of the Syrian civil war. Similar processes took place in the eastern outskirts of Damascus, Homs, al-Raqqah and along the threshold of the great Syrian and Northern Iraqi Deserts. These transformations impact upon cities, themselves a set of entangled natural/man-made environments. The conflict and hardships along desertification bands compel dispossessed farmers to embark upon increasingly perilous paths of migrations, leading to fast urbanization at the growing outskirts of the cities and slams.

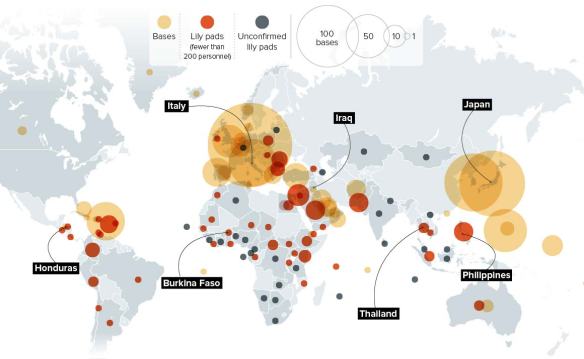

I’m trying to understand these processes across desert thresholds. There has been a very long colonial debate about what is the line beyond which the desert begins. Most commonly it was defined as 200 mm rain per annum. Cartographers were trying to draw it, as it represented, to a certain extent, the limit of imperial control. From this line on, most policing was done through bombing of tribal areas from the air. Since the beginning, the emergence of the use of air power in policing in the post World War I period—aerial control, aerial government—took form in places that were perceived, at the time, as lying beyond the thresholds or edges of the law. The British policing of Iraq, the French in Syria, and Algeria, the Italians in Libya are examples where control would hover in air.

Up to now I was writing about borders that were physical and manmade: walls in the West Bank or Gaza and the siege around it—most notably in Hollow Land (2007). Now I started to write about borders that are made by the interaction of people and the environment—like the desert line—which is not less violent and brutal. The colonial history of Palestine has been an attempt to push the line of the desert south, trying to make it green or bloom—this is in Ben Gurion’s terms—but the origins of this statement are earlier and making the desert green and pushing the line of the desert was also Mussolini’s stated aim. On the other hand, climate change is now pushing that line north.

Following not geopolitical but meteorological borders, helps me cut across a big epistemological problem that confines the writing in international relations or geopolitics within the borders organize your writing. Braudel is an inspiration but, for him, the environment of the Mediterranean is basically cyclically fixed. The problem with geographical determinism is that it takes nature as a given, cyclical, milieu which then affects politics—but I think we are now in a period where politics affects nature in the same way in which nature affects politics. The climate is changing in the same speed as human history.

The conflict shoreline was originally commissioned in response to Fazal Sheikh’s Desert Bloom series (part of his remarkable Erasure trilogy: see image stream above, and also here).

It has also been submitted as evidence for Zochrot‘s project on transitional justice, the Truth Commission on the responsibility of Israeli society for the events of 1948–1960 in the South.

Transitional justice mechanisms address the needs of communities and countries in conflict to cope with systematic abuses and structural injustices in order to facilitate reconciliation. Communities in conflict, both victims and victimizers, have developed a variety of innovative approaches to addressing the needs that result from ongoing conflicts. Hitherto, practices informed by the transitional justice paradigm have been used mainly to accompany and heal societies and communities in political transitions such as from totalitarian to democratic rule, or from an apartheid regime as in South Africa to an egalitarian democratic regime. Usually, these practices have been applied after a violent conflict had ended in a peace agreement, as in the former Yugoslavia, or in an armistice, as in Cyprus or Northern Ireland.

Many activists around the world have demonstrated time and again that silencing and ignoring the past prevent conflict resolution and the attainment of true reconciliation. Therefore, even in situations of seemingly intractable conflicts, several initiatives by civil society organizations, trade union or social religious organizations similar to state-sponsored mechanisms of transitional justice have sprung around the world. For the past 40 years, these initiatives have acted without government backing to bring resolve violent conflicts.

The Truth Commission established by Zochrot now joins these initiatives. The first of its kind in Israel/Palestine, the Commission is unique in that … it is active while the conflict is still ongoing, and against the background of the regime’s evasion of responsibility to the events of the Nakba, which began in 1948 and is still ongoing [the Nakba or ‘catastrophe’ refers to the forced eviction and dispossession of the Palestinian people set in motion by the war of 1948]. The Truth Commission for Exposing Israeli Society’s Responsibility for the Events of 1948-1960 in the South which started its deliberations in late October 2014…

The Commission seeks to expose the events of the Nakba during those years – events that have profound implications for the ongoing Nakba experienced by the Palestinian Bedouins to this day. The Commission examines testimonies by Palestinian displaced persons and refugees, as well as Jews who lived in the south and Jewish fighters who took part in displacement and expulsion operations in the area. In addition, the Commission peruses relevant archive materials. The Commission’s report will be designed to encourage the Jewish society in Israel to accept responsibility for past injustices in the south, with reference to the ongoing Nakba, and for redressing them.

You can also read Tom Pessah‘s report for +972 here.