Here is the first of a series of updates on Syria, this one identifying recent work on attacks on hospitals and health care which I’ve been reading while I turn my previous posts into a long-form essay (see ‘Your turn, doctor‘ and ‘The Death of the Clinic‘).

First, some context. Human Rights Watch has joined a chorus of NGOs documenting attacks on hospitals and health care around the world. On 24 May HRW issued this bleak statement:

Deadly attacks on hospitals and medical workers in conflicts around the world remain uninvestigated and unpunished a year after the United Nations Security Council called for greater action, Human Rights Watch said today.

On May 25, 2017, UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres is scheduled to brief the Security Council on the implementation of Resolution 2286, which condemned wartime attacks on health facilities and urged governments to act against those responsible. Guterres should commit to alerting the Security Council of all future attacks on healthcare facilities on an ongoing rather than annual basis.

“Attacks on hospitals challenge the very foundation of the laws of war, and are unlikely to stop as long as those responsible for the attacks can get away with them,” said Bruno Stagno-Ugarte, deputy executive director for advocacy at Human Rights Watch. “Attacks on hospitals are especially insidious, because when you destroy a hospital and kill its health workers, you’re also risking the lives of those who will need their care in the future.”

The statement continues:

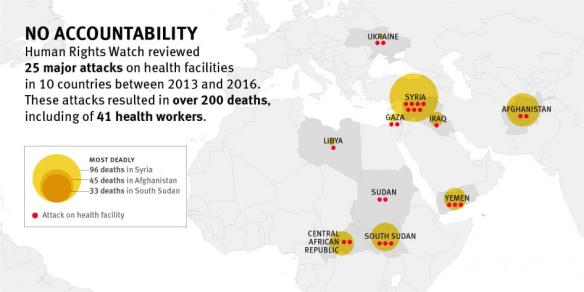

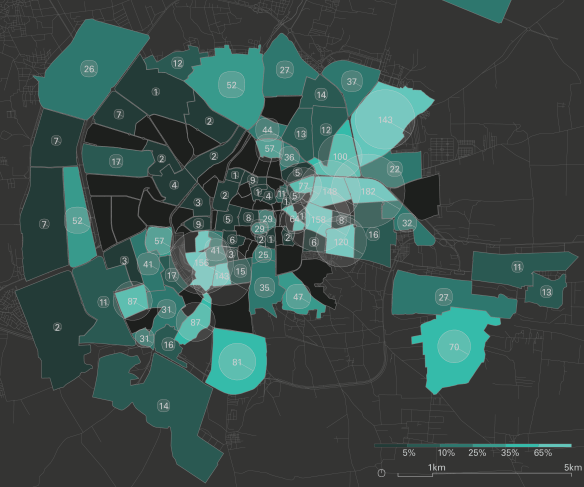

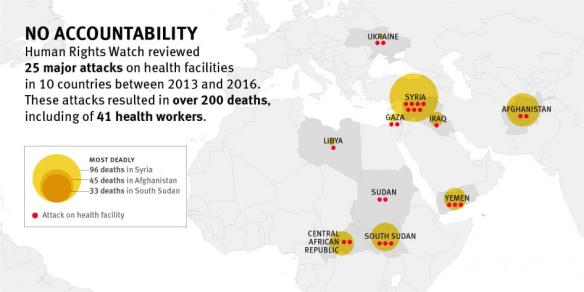

International humanitarian law, also known as the laws of war, prohibits attacks on health facilities and medical workers. To assess accountability measures undertaken for such attacks, Human Rights Watch reviewed 25 major attacks on health facilities between 2013 and 2016 in 10 countries [see map above]. For 20 of the incidents, no publicly available information indicates that investigations took place. In many cases, authorities did not respond to requests for information about the status of investigations. Investigations into the remaining five were seriously flawed…

No one appears to have faced criminal charges for their role in any of these attacks, at least 16 of which may have constituted war crimes. The attacks involved military forces or armed groups from Afghanistan, Central African Republic, Iraq, Israel, Libya, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Ukraine, and the United States.

More here.

The World Health Organisation reached similar conclusions in its report of 17 May 2017:

Alexandra Sifferlin‘s commentary for Time drew attention to the importance of attacks on medical facilities in Syria:

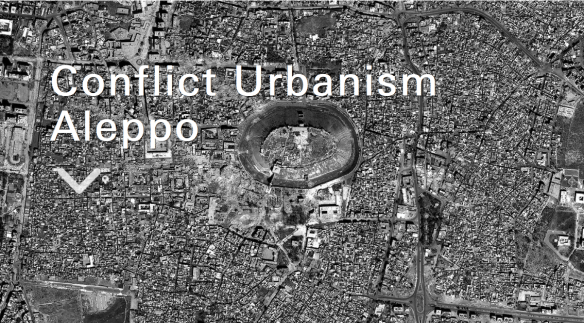

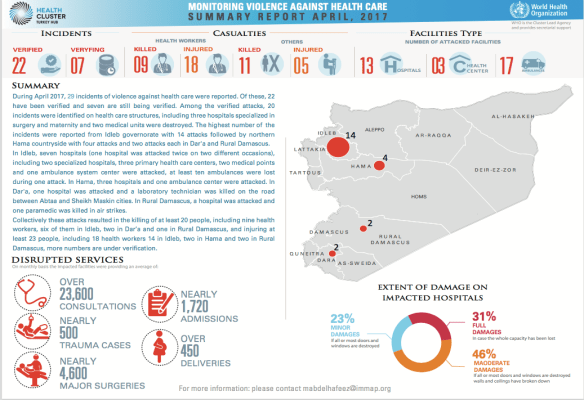

In a 48-hour period in November, warplanes bombed five hospitals in Syria, leaving Aleppo’s rebel-controlled section without a functioning hospital. The loss of the Aleppo facilities — which had been handling more than 1,500 major surgeries each month — was just one hit in a series of escalating attacks on health care workers in 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported on Friday.

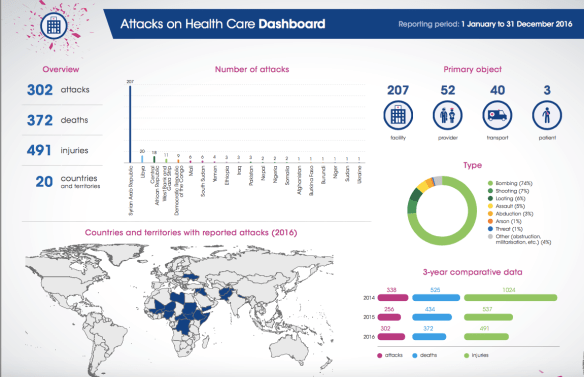

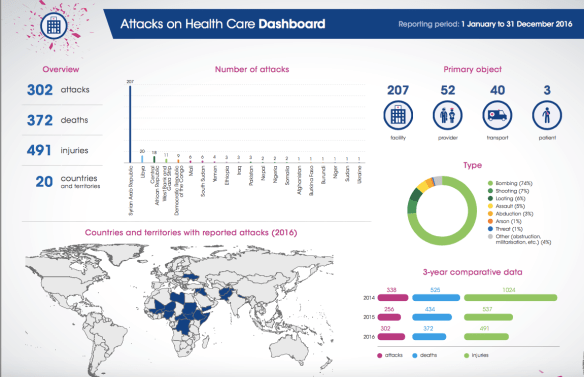

Violent attacks on hospitals and health workers “continue with alarming frequency,” the WHO said in its new report. In 2016, there were 302 violent attacks, which is about an 18% increase from the prior year, according to new data. The violence — 74% was in the form of bombings — occurred in 20 countries, but it was driven by relentless strikes on health facilities in Syria, which the WHO has previously condemned. Across the globe, the 302 attacks last year resulted in 372 deaths and 491 injuries…

After the spate of attacks on Syrian hospitals last November, the WHO reported that three of the bombed hospitals in Aleppo had been providing over 10,000 consultations every month. Two other bombed hospitals in the city of Idleb were providing similar levels of care, including 600 infant deliveries. One of the two hospitals in Idleb was a primary referral hospital for emergency childbirth care.

“The attack…is an outrage that puts many more lives in danger in Syria and deprives the most vulnerable – including children and pregnant women – of their right to health services, just at the time when they need them most,” the WHO said.

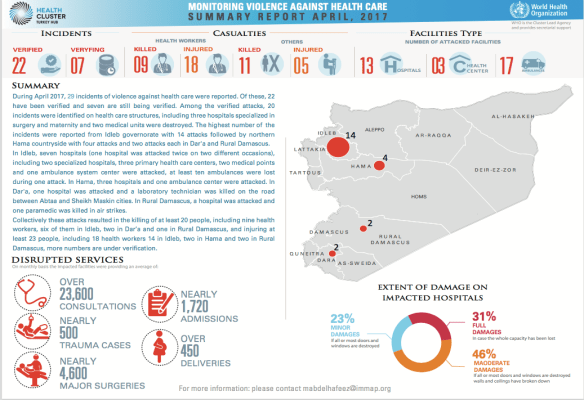

The WHO has also provided a series of reports on attacks on hospitals and health care in Syria; here is its summary for last month:

But the WHO’s role in the conflict in Syria has been sharply criticised by Annie Sparrow, who has accused it of becoming a de facto apologist for the Assad regime. Writing in Middle East Eye earlier this year, she said:

For years now, the World Health Organisation (WHO) has been fiddling while Syria burns, bleeds and starves. Despite WHO Syria having spent hundreds of millions of dollars since the conflict began in March 2011, public health in Syria has gone from troubling in 2011 to catastrophic now…

Yet WHO Syria has been anything but an impartial agency serving the needy. As can be seen by a speech made by Elizabeth Hoff, WHO’s representative to Syria, to the UN Security Council (UNSC) on 19 November 2016, WHO has prioritised warm relations with the Syrian government over meeting the most acute needs of the Syrian people.

Annie singles out three particularly problematic issues.

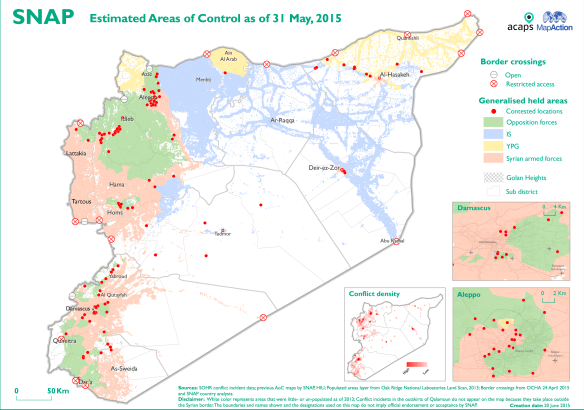

- She claims that the WHO parrots the Assad regime’s claim that before the conflict its vaccination programmes had covered 95 per cent of the population (or better), whereas she insists that vaccinations had been withheld from children ‘in areas considered politically unsympathetic, such as the provinces of Idlib, western Aleppo, and Deir Ezzor.’ On her reading, in consequence, the re-emergence of (for example) polio ‘is consistent with pre-existing low immunisation rates and the vulnerability of Syrian children living in government-shunned areas.’

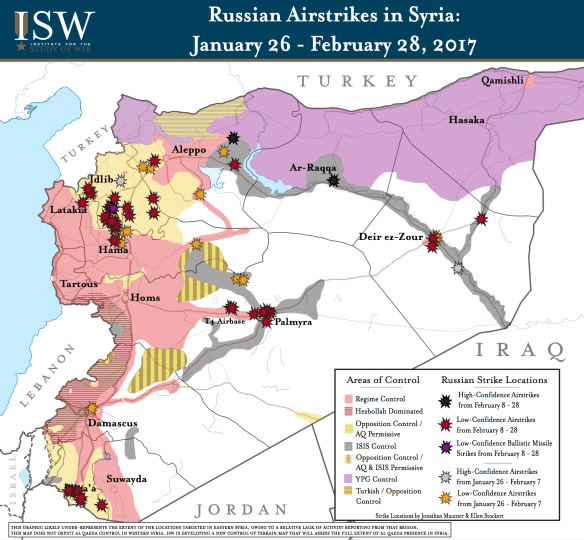

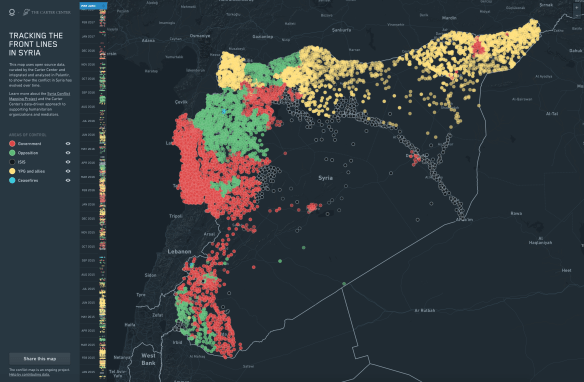

- It was not until 2016 that the WHO reported attacks on hospitals at all, and when its representative condemned ‘repeated attacks on healthcare facilities in Syria’ she failed to note that the vast majority of those attacks were carried out by the Syrian Arab Air Force and its Russian ally. The geography of deprivation was erased: ‘It is only in opposition-held areas that healthcare is compromised because of the damage and destruction resulting from air strikes by pro-government forces.’

- Those corpo-materialities – an elemental human geography, so to say – did emerge when the WHO accused the Assad regime of of ‘withholding approval for the delivery of surgical and medical supplies to “hard-to-reach” and “besieged” locations.’ But Annie objects to these ‘politically neutral terms’ because they are ‘euphemisms for opposition-controlled territory, and so [avoid] highlighting the political dimension of the aid blockages, or the responsibility of the government for 98 percent of the more than one million people forced to live in an area under siege.’

You can read WHO’s (I think highly selective) response here.

Earlier this month 13 Syrian medical organisations combined with the Syria Campaign to document how attacks on hospitals have driven hospitals and health facilities underground (I described this process – and the attacks on the Cave Hospital and the underground M10 hospital in Aleppo – in ‘Your turn, doctor‘). In Saving Lives Underground, they write:

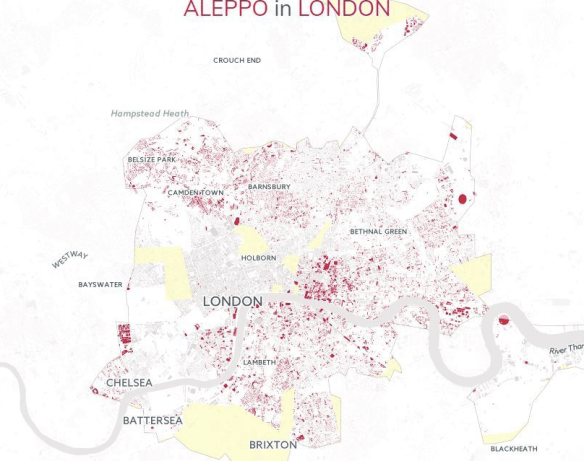

Health facilities in Syria are systematically targeted on a scale unprecedented in modern history.

Health facilities in Syria are systematically targeted on a scale unprecedented in modern history.

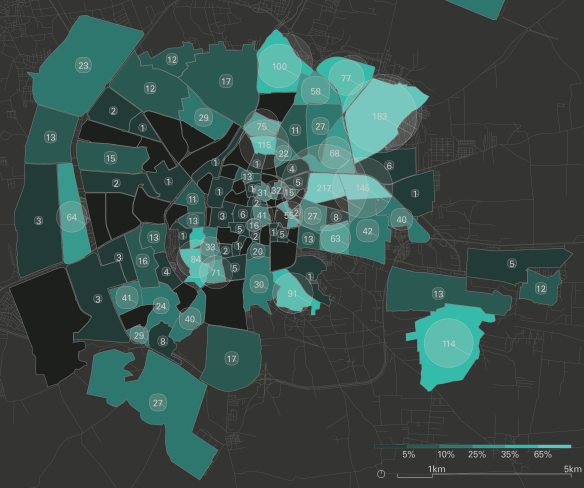

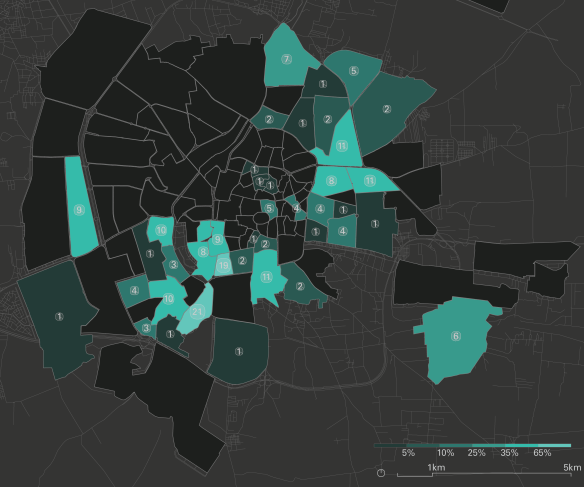

There have been over 454 attacks on hospitals in the last six years, with 91% of the attacks perpetrated by the Assad government and Russia. During the last six months of 2016, the rate of attacks on healthcare increased dramatically. Most recently, in April 2017 alone, there were 25 attacks on medical facilities, or one attack every 29 hours.

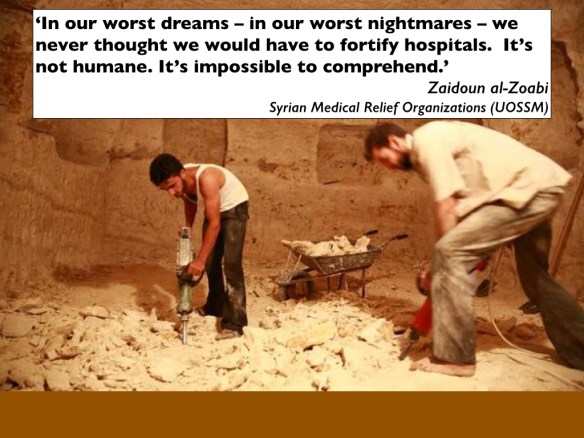

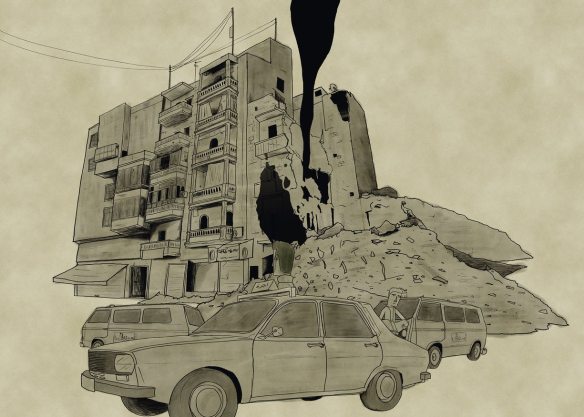

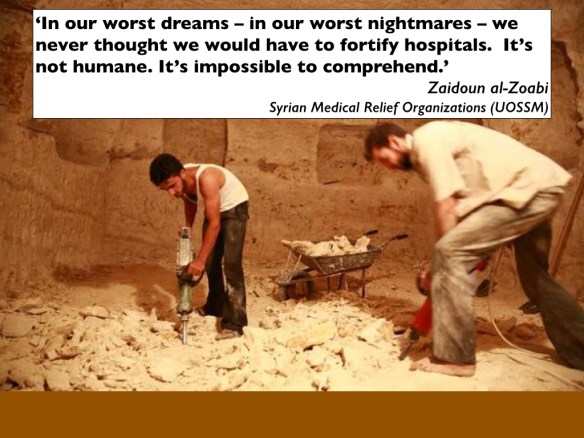

While the international community fails to protect Syrian medics from systematic aerial attacks on their hospitals, Syrians have developed an entire underground system to help protect patients and medical colleagues as best they can. The fortification of medical facilities is now considered a standard practice in Syria. Field hospitals have been driven underground, into basements, fortified with sandbags and cement walls, and into caves. These facilities have saved the lives of countless health workers and patients, preserved critical donor-funded equipment, and helped prevent displacement by providing communities with emergency care.

But all this comes at a cost:

Donors often see the reinforcement and building of underground medical facilities exclusively as long-term aid, or development work. However, as the Syria crisis is classified as a protracted emergency conflict, medical organizations do not currently have access to such long-term funds.

Budget lines for the emergency funding they receive can include “protection” work, but infrastructure building, even for protective purposes, often falls outside of their mandate. The divide between emergency humanitarian and development funding is creating a gap for projects that bridge the two, like protective measures for hospitals in Syria.

For this reason, as Emma Beals reported in the Guardian, many projects have resorted to crowdfunding:

The latest underground medical project seeking crowdfunding to complete building works is the Avicenna women and children’s hospital in Idlib City, championed by Khaled al-Milaji, head of the Sustainable International Medical Relief Organisation.

Al-Milaji is working to raise money with colleagues from Brown University in the US, where he studied until extreme security vetting – the Trump administration’s “Muslim ban” – prevented him re-entering the country after a holiday in Turkey.

He has instead turned his attention to building reinforced underground levels of the hospital, sourcing private donations to meet the shortfall between donor funding and actual costs…

Crowdfunding was an essential part of building the children’s Hope hospital, near Jarabulus in northern Syria. The project is run by doctors from eastern Aleppo, who were evacuated from the city in December after it was besieged for nearly six months amid a heavy military campaign. Doctors worked with the People’s Convoy, which transported vital medical supplies from London to southern Turkey as well as raising funds to build the hospital, which opened in April. More than 4,800 single donations raised the building costs, with enough left over to run the hospital for six months.

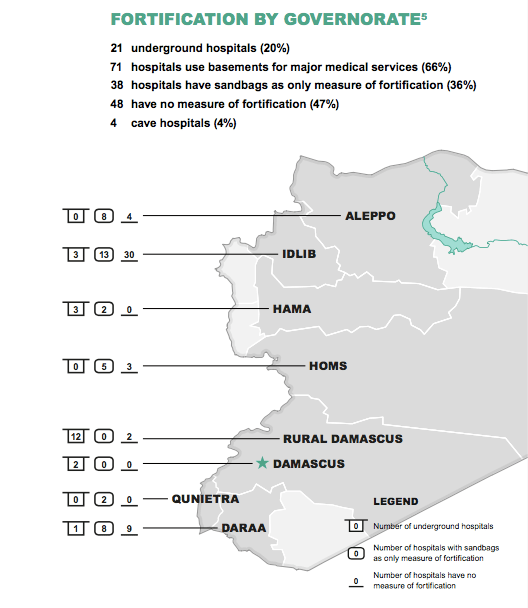

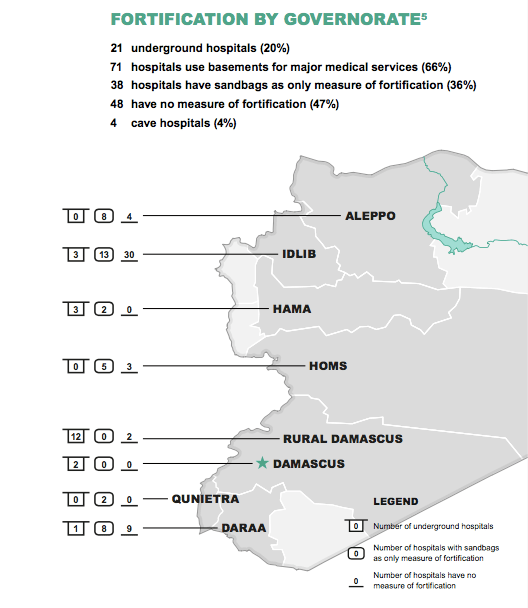

Saving Lives Underground distinguishes basement hospitals (the most common response to aerial attack by aircraft or shelling: 66 per cent of fortified hospitals fall into this category; the average cost is usually around $80–175,000, though more elaborate rehabilitation and repurposing can run up to $1 million); cave hospitals (‘the more effective protection model’ – though there are no guarantees – which accounts for around 4 per cent of fortified hospitals and which typically cost around $200–800,000) and purpose-built underground hospitals (two per cent of the total; these can cost from $800,000 to $1,500,000).

It’s chilling to think that hospitals have to be fortified and concealed in these ways: but even more disturbing, the report finds that 47 per cent of hospitals in these vulnerable areas have no fortification at all.

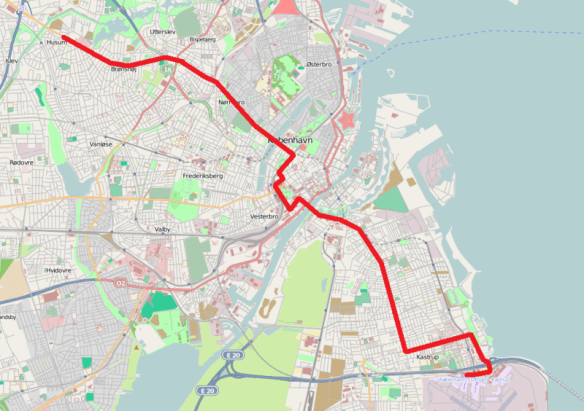

Seriously ill or wounded patients trapped inside besieged areas have few choices: medical facilities are degraded and often makeshift; access to vital medical supplies continues to be capriciously controlled and often denied; and attempts to evacuate them depend on short-lived ceasefires and deals (or bribes). In Aleppo control of the Castello Road determined whether ambulances could successfully run the gauntlet from eastern Aleppo either west to hospitals in Reyhanli in Turkey or out to the Bab-al Salama Hospital in northern Aleppo and then across the border to state-run hospitals in Kilis: but in the absence of a formal agreement this was often a journey of last resort.

A victim of a barrel bomb attack in Aleppo is helped into a Turkish ambulance on call at the Bab al Salama Hospital near the Turkish border.

In October 2016 there were repeated attempts to broker medical evacuations from eastern Aleppo; eventually an agreement was reached, but the planned evacuations were stalled and then abandoned. In December a new ‘humanitarian pause’ agreed with Russia and the Syrian government allowed more than 100 ambulances to be deployed by the Red Cross and the Red Crescent from Turkey; 200 critical patients were ferried from eastern Aleppo to hospitals in rural Aleppo, Idlib or Turkey – but the mission was abruptly terminated 24 hours after it had started.

The sick and injured have continued to make precarious journeys to hospitals in Turkey (Bab al-Hawa, Kilis, Reyhanli and other towns along the border: see here, here and here), and also Jordan (in Ramtha and Amman, and in the Zaatari refugee camp: see here and here), Lebanon (in Beirut, Tripoli and clinics in the Bekaa Valley), and even Israel (trekking across the Golan Heights into Northern Israel: see here, here, here and especially here).

But there are no guarantees; travelling within Syria is dangerous and debilitating for patients, and access to hospitals outside Syria is frequently disrupted by border closures (which in turn can thrust the desperate into the hands of smugglers). In March 2016, for example, Amnesty International reported:

Since 2012 Jordan has imposed increasing restrictions on access for Syrians attempting to enter the country through formal and informal border crossings. It has made an exception for Syrians with war-related injuries. However, Amnesty International has gathered information from humanitarian workers and family members of Syrian refugees with critical injuries being denied entry to Jordan for medical care, suggesting the exceptional criteria for entry on emergency medical grounds is inconsistently applied. This has led to refugees with critical injuries being returned to field hospitals in Syria, which are under attack on a regular basis, and to some people dying at the border.

In June Jordan closed the border, after an IS car bomb killed seven of its soldiers, and by December MSF had been forced to close its clinic at the Zaatari camp, which had provided post-operative care for casualties brought in from Dara’a.

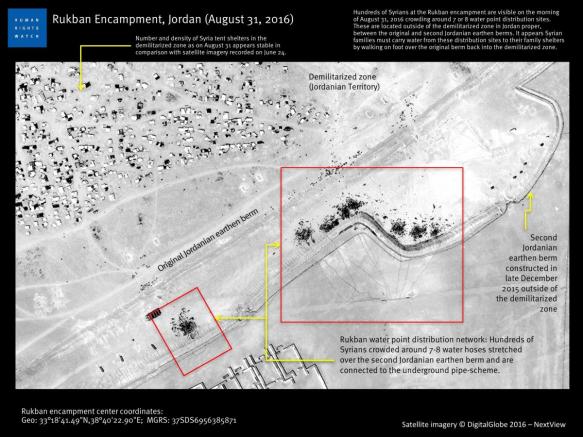

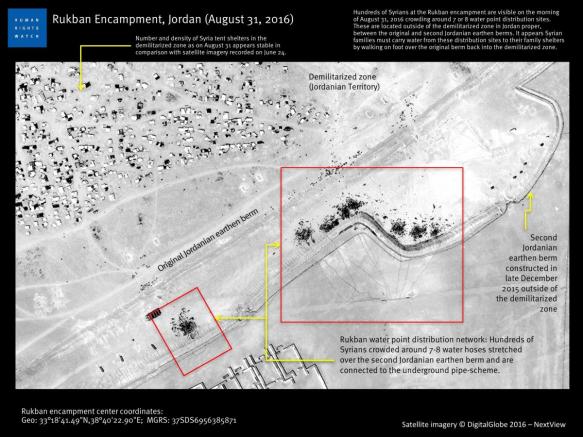

Tens of thousands of refugees are now trapped in a vast, informal encampment (see image above) between two desert berms in a sort of ‘no man’s land‘ between Syria and Jordan. From there Jordanian troops transport selected patients to a UN clinic, located across the border in a sealed military zone – ‘and then take them back again to the checkpoint after they are treated.’

(For the image above, and a commentary by MSF’s Jason Cone, see here).

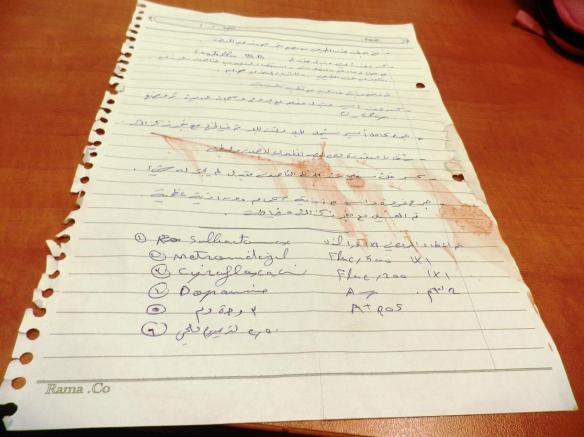

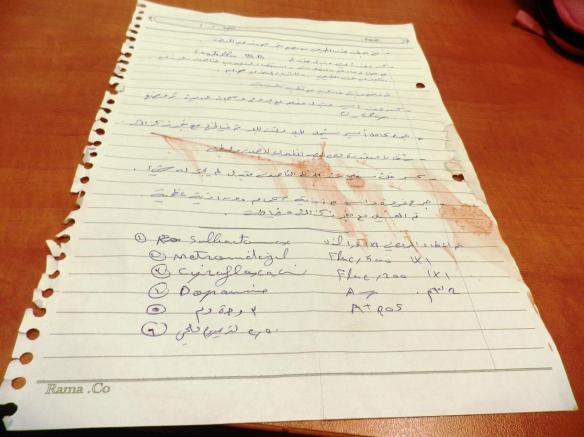

For patients who do manage to make it across any of these borders, it’s far from easy for doctors to recover their medical history – as the note below, pinned to an unconscious patient who was admitted to the Ziv Medical Center in Safed implies – and in the case of Syria (as in Iraq) everything is further complicated by a fraught politics of the wound.

Here, for example, is Professor Ghassan Abu-Sitta, head of plastic and reconstructive surgery at the medical centre in Beirut, talking earlier this month with Robert Fisk:

In Iraq, patients wounded in Saddam’s wars were initially treated as heroes – they had fought for their country against non-Arab Iran. But after the US invasion of 2003, they became an embarrassment. “The value of their wounds’ ‘capital’ changes from hero to zero,” Abu-Sitta says. “And this means that their ability to access medical care also changes. We are now reading the history of the region through the wounds. War’s wounds carry with them the narrative of the wounding which becomes political capital.”

In the bleak wars that have scarred Syria, and which continue to open up divisions and divides there too, the same considerations come into play with equal force.