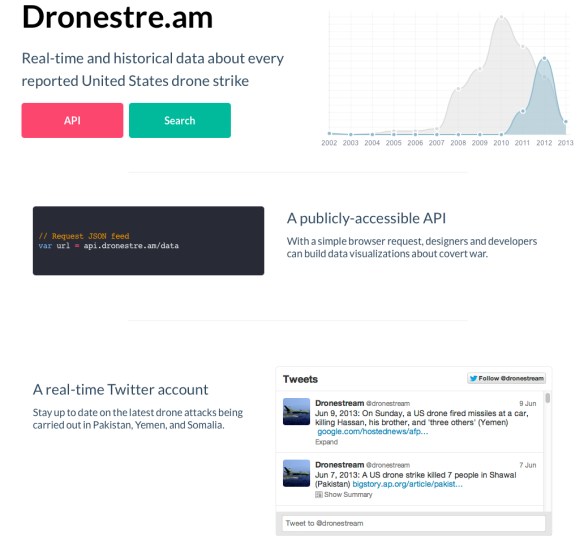

A key moment in the development of the United States’ UAV program was the deployment of a prototype Predator – General Atomics’ GNAT-750 – over Bosnia. This is how I summarised the accelerated fielding program in ‘Moving targets’ (DOWNLOADS tab):

Even as the GNAT-750 was deployed over Bosnia-Herzegovina, the design was being developed into a new platform, the RQ-1 Predator, which incorporated three major modifications. The original intention had been to provide still imagery and text interpretation, but this was replaced by real-time motion video in colour (by day) and infrared (by night). A more serious limitation was range; the GNAT-750 could only operate 150 miles from the ground control station because it relied on a C-band line of sight data link. The CIA experimented with using relay aircraft to expedite data transmission – the same solution that had been used for the ‘electronic battlefield’ along the Ho Chi Minh Trail – but the breakthrough came with the use of the Ku-band satellite system that dramatically increased the operational range. The upgrade had been tested in the United States, and was retrofitted to Predators in Europe in August 1995. Although data was then rapidly transmitted across the Atlantic, the key intelligence nodes were still in Europe, like the Combined Air Operations Centre at Vicenza in Italy, and the drones were still controlled from ground stations within the region, at first from Gjader in Albania and later from Tazar in Hungary. A third, no less revolutionary innovation was the installation of an onboard global positioning system (GPS); early target imagery had to be geo-located using a PowerScene software program, but the introduction of satellite-linked GPS made a considerable difference to the speed and accuracy of targeting.

But I now think this misses other even more important dimensions that speak directly to the fabrication of the network in which Predators and eventually Reapers become embedded.

My primary source is a remarkable MIT PhD thesis by Lt. Col. Timothy Cullen, The MQ-9 Reaper Remotely Piloted Aircraft: Humans and Machines in Action (2011). The research involved interviews with 50 pilots, 26 sensor operators, 13 Mission Intelligence Coordinators and 8 imagery analysts between 2009-2010 (so this is inevitably a snapshot of a changing program – but one with a wide field of view) and direct observation of training missions at Holloman Air Force Base; the thesis is also informed by Cullen’s own, considerable experience as a pilot of conventional strike aircraft and by actor-network theory, though most particularly by Edward Hutchins‘ cognitive ethnography and by the work of Lucy Suchman.

I should say, too, that the thesis is irony made flesh, so to speak. The author notes that:

I should say, too, that the thesis is irony made flesh, so to speak. The author notes that:

Missing from public discussions are the details of remote air operations in current conflicts and the role of social networks, organizational culture, and professional practices in the evolution and history of RPA. The public cannot have informed discussions about these topics without empirical observations and descriptions of how RPA operators actually fly and employ the aircraft.

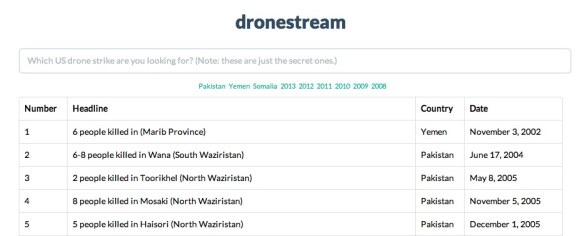

Fair enough, of course, but parts of the thesis are heavily redacted; I realise this isn’t – can’t – be Cullen’s doing, but it is as frustrating for the reader as it surely must be for the author (for Private Eye devotees, the image on the right shows p. 94). Still, there’s enough in plain sight to provide a series of arresting insights into the development of the UAV program.

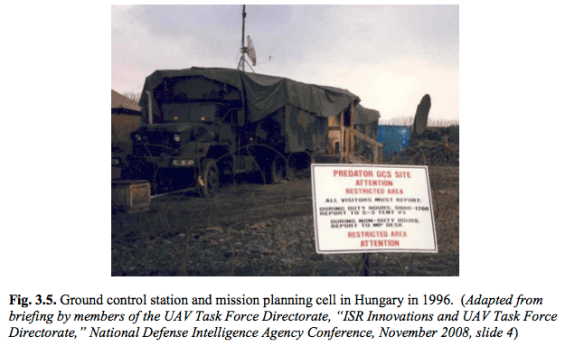

First, early Predator crews were remarkably detached from the wider mission and their ability to communicate with people outside their Ground Control Stations was extremely limited. The pilot’s primary responsibility was to program the aircraft to fly on autopilot from target to target and to monitor the flight path, while two sensor operators identified and tracked the targets whose images were to be captured. In a tent outside the ground control station a ‘Mission Planning Cell’ (MPC: see photograph below) served as the communications interface; since this was an experimental system, the Ground Control Station was not permitted to receive or transmit sensitive or classified information. Apart from the transmission of images, all communications between the two were either face-to-face (literally through the tent flaps) or via a telephone link.

Before a mission the MPC received a set of 50-300 imagery targets (known as ‘Collection Points’) from the Balkans Combined Air Operations Center in Vicenza in Italy, and used this to create a detailed target deck. The time between the initial requests and final image capture steadily decreased from 72 hours to 48 hours, and eventually re-tasking during a mission became standard: more on the tasking process here.

The video feeds from the Predator were sent via coaxial cable to the MPC where they were digitised and encrypted for onward transmission over a secure network to commanders in the field and to a group of 10-12 imagery analysts in the United States. The analysts posted video clips and annotated stills on a classified web page, but the quality of the video feeds with which they had to work was significantly less than the raw feeds available in theatre, and the slow response time was another serious limitation on the value of their work.

The video feeds from the Predator were sent via coaxial cable to the MPC where they were digitised and encrypted for onward transmission over a secure network to commanders in the field and to a group of 10-12 imagery analysts in the United States. The analysts posted video clips and annotated stills on a classified web page, but the quality of the video feeds with which they had to work was significantly less than the raw feeds available in theatre, and the slow response time was another serious limitation on the value of their work.

At the time, of course, all this seemed revolutionary, and the second Annual Report on the UAV program in 1996 declared that:

Even more significant than the Predator performance “firsts” is the wide use made of its imagery, amplified by the increased network of receiving stations both in-theater and back in CONUS [continental US]. The development of this dissemination capability is shown below.

It first used VSATs at selected receiving sites, and then the SATCOM-based Joint Broadcast System (JBS). The Predator-JBS network represents the first time for the simultaneous broadcast of live UAV video to more than 15 users. This provided a common picture of the “battlefield.” Video imagery can be viewed either as full motion video or via a “mosaicking” technique at the ground station.

[JAC Molesworth was the Joint Analysis Center at RAF Molesworth in the UK, US European Command’s intelligence center, and DISN is the Defense Information Systems Network for data, video and voice services].

But the system was far from responsive; the MPC filtered all communications from commanders and imagery analysts and, as the tasking diagram below shows, whether the cycle followed the standard model or allowed for more flexible re-tasking the Predator crew had very little discretion and was, in a substantial sense, what Cullen calls ‘a passive source of data’. Its responsibilities were limited to the ‘physical control’ of the platform.

This has been transformed by the cumulative construction of an extended, distributed network in which UAV crews are in direct communication, either by voice or through secure internet chatrooms, with multiple agents: commanders, military lawyers, image analysts, joint terminal attack controllers and ground troops. But this was not how the system was originally conceived or fielded, and Cullen shows that its transformation depended on the skilled intervention of UAV crews and their commanders who ‘envisioned and used the system as a collaborative network of operators, intelligence analysts, and ground personnel to establish objectives, exchange information, and understand the context of a mission’:

‘RPA [Remotely Piloted Aircraft] operators restructured the ground control station and crew tasks to shift the actions of crewmembers from low status missions of gathering and disseminating data to higher status tasks of integrating and creating information, participating in the assessment of threats, and actively contributing to commanders’ decision-making processes. RPA operators were not satisfied with simple connections to a network of people and tools to accomplish a mission. They sought and fostered social relationships with them and demanded interactive dialog among them in a form they could anticipate, understand, and evaluate’ (Cullen, p. 204).

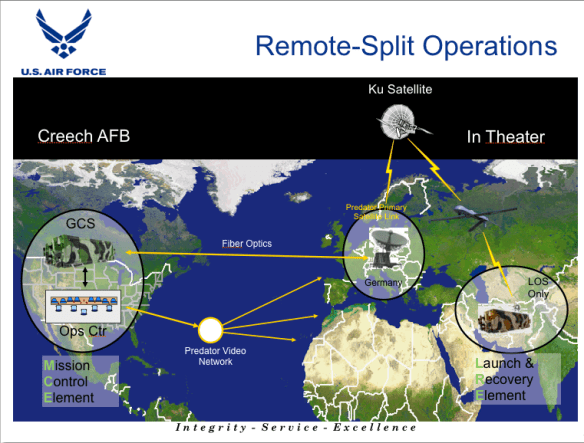

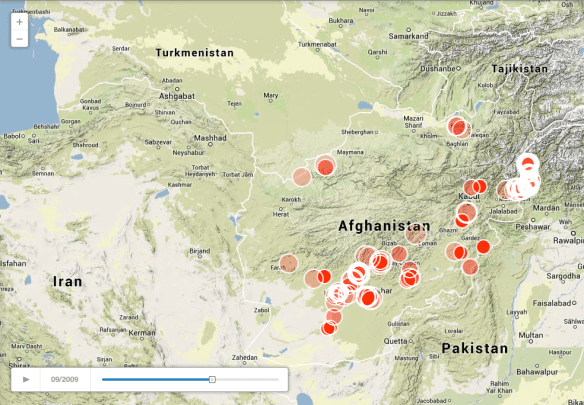

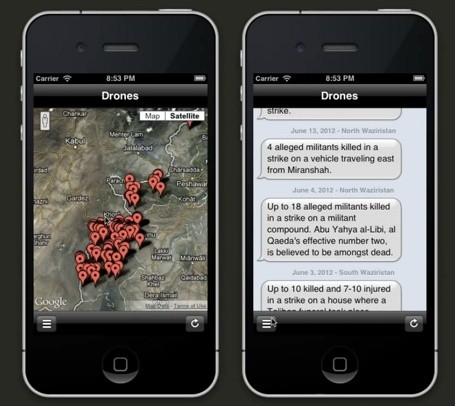

Second, early Predator operations, not only in the Balkans in the late 1990s but also over southern Iraq and in Afghanistan, were not what would later become known as ‘remote-split operations’. It was assumed that the Predator had to be operated as close to the combat theatre as possible. This was not only because of the platform’s limited range, important though this is: as I’ve said before, these are not weapons of global reach. Indeed, it’s still the case that Predators and Reapers have to be physically close to their theatre of operations, which is why the United States has become so alarmed at the implications of a complete withdrawal from Afghanistan for the CIA’s program of targeted killing in Pakistan. According to David Sanger and Eric Schmitt,

‘Their concern is that the nearest alternative bases are too far away for drones to reach the mountainous territory in Pakistan where the remnants of Al Qaeda’s central command are hiding. Those bases would also be too distant to monitor and respond as quickly as American forces can today if there were a crisis in the region, such as missing nuclear material or weapons in Pakistan and India.’

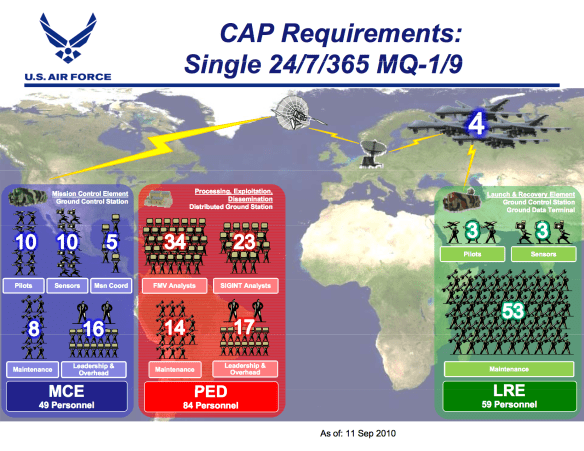

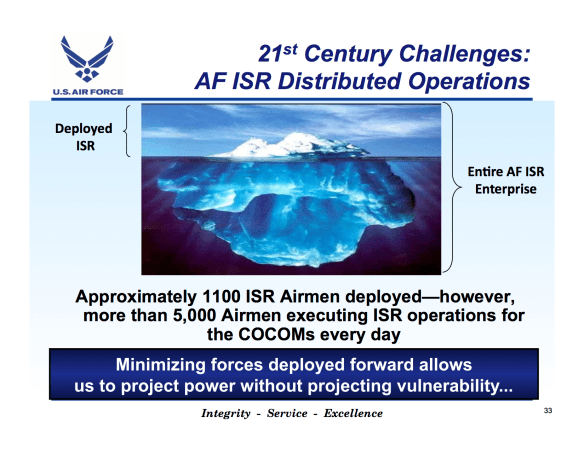

For the ‘no-fly zone’ established over southern Iraq reconnaissance flights were flown by Predators from Ali Al Salem Air Base in Kuwait, and for the initial campaign in Afghanistan from Jacobad in Pakistan, and Cullen explains that the vulnerability of these (‘austere’) sites limited the MPC’s access to secure networks, communications and databases. But in 2002-3 USAF pilots and sensor operators returning from secondment to – Cullen actually calls it ‘kidnapping’ – ‘other agencies’, which is to say the CIA, successfully argued that the primary execution of remote missions should be consolidated at Nellis Air Force Base and its auxiliary field, Indian Springs (later re-named Creech AFB), in southern Nevada, which would expand and enhance crews’ access to secure intelligence and analysis capabilities. There would still have to be a forward deployed ‘Launch and Recovery’ element to maintain the aircraft and to control take-off and landing using a line of sight link, but all other mission tasks could be handled from the continental United States using a Ku-band satellite link via a portal at Ramstein Air Force Base in Germany. When remote split operations started in 2003 the MPC disappeared, replaced by a single Mission Intelligence Co-ordinator who was stationed inside the Ground Control Station in constant communication with the pilot and sensor operator and this, in turn, transformed the configuration and equipment inside the GCS. But, crucially, relations beyond the GCS were also transformed as USAF commanders visited Afghanistan and Iraq and established close relations with ground troops: ‘remote’ and ‘split’ could not imply detachment, and the new technological networks had to be infused with new social interactions for the system to be effective.

Focal to these transformations – and a crucial driver of the process of network construction and transformation – was the decision to arm the Predator and turn it into a ‘hunter-killer’ platform. At that point, Cullen observes,

‘Predator pilots became decision makers, and Predator’s weapons transformed Predator pilots and sensor operators into war fighters – Predator crews could create effects on the battlefield they could observe, evaluate and adjust… The arming of the Predator was synonymous with the integration of the system – the people, tools and practices of the Predator community – into military operations’ (pp. 245-7).

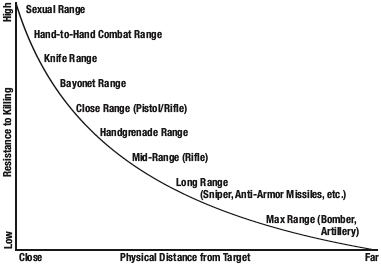

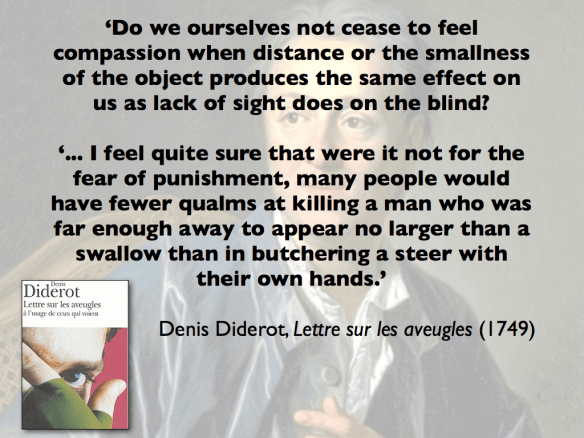

The reverse was also true: not only was the Predator integrated into the battlespace but, as Cullen notes, the network was ‘infused’ into the Ground Control Station. In consequence, a sensation of what Cullen calls ‘remote presence’ was inculcated amongst UAV crews and, in particular, sensor operators who developed a strong sense of being part of the machinic complex, ‘becoming the camera’ so intimately that they were ‘transported’ above the battlespace. These transformations were stepped up with the development of the Reaper, reinforced by new practices and by the introduction of a new, profoundly combative discourse that distanced the Reaper from the Predator:

‘[T]o reinforce the power and responsibility of Reaper crews, members of the 42nd Attack Squadron changed the language of their work. Sensor operators did not operate a sensor ball; they flew a “targeting pod” like fighter pilots and weapon system officers. Reaper pilots and sensor operators did not have a “mission intelligence coordinator”; they coordinated strike missions with the support of an “intelligence crewmember.” Reaper crews did not conduct “intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance” missions; they flew “non-traditional” intelligence missions like fighter and bomber crews. Members of the 42nd Attack Squadron used the rhetoric of the fighter community to highlight the strike capabilities of Reaper; to influence the perceptions of Reaper operators; and to shape the priorities, attention, and assertiveness of Reaper crews during a mission’ (p. 264)

The language was performative, but its performative force – the ability to ‘create effects on the battlefield’ – was realised through the developing networks within which and through which it was deployed.

To be continued.