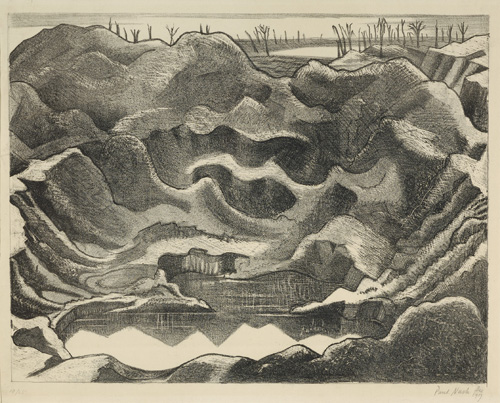

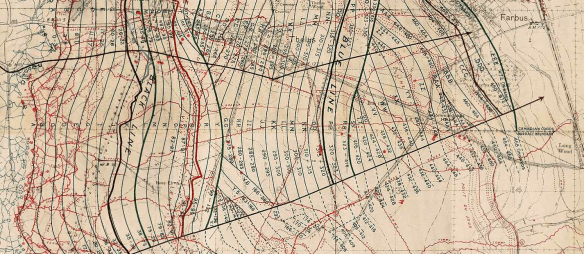

Ever since I heard Isla Forsyth give one of her marvellous presentations on camouflage I’ve been fascinated by the subject – all the more so since it intersects so artfully (and, as Isla would quite rightly insist, scientifically) with my work on aerial reconnaissance, bombing and modern war. You can get an early sense of Isla’s work from this presentation, ‘Shadow chasers: exploring the vertical and angular geometries of camouflage‘, which includes a gallery of images. Isla’s Glasgow PhD thesis, From Dazzle to the Desert: A Cultural-Historical Geography of Camouflage, was completed last year – and I hope will appear in book form.

There’s a great blog on camouflage – Camoupedia – which includes an appreciative notice of Isla’s work and, amongst a feast of deceptive riches, a stunning series of posters by graphic design students to advertise a talk by Claudia Covert (that really is her splendid name) on dazzle ship camouflage in World War I, a post about the newspaper of the American Camouflage Corps in 1917 (above), and a remarkable extract from a letter from Reginald Farrer later published as The Void of War: letters from three fronts (1918):

The real thing about the human side of the war is the sheer fun of it. In certain aspects the war is nothing but a glorious, gigantic game of hide and seek—camouflage is nothing else. It is not only the art of making things invisible, but also of making them look like something else. Even the art of inconspicuousness is subtle and exciting. What glory it must be to splash your tents and lorries all over with wild waggles of orange and emerald and ochre and umber, in a drunken chaos, until you have produced a perfect futurist masterpiece which one would think would pierce the very vaults of heaven with its yells..

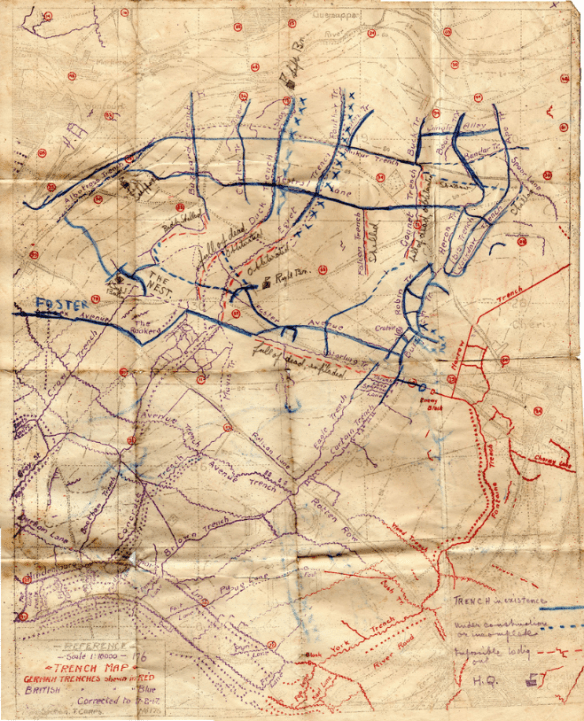

But disguise is an even higher branch of the art: you go on to make everything look like something else. Hermit crabs and caddis worms become our masters. Down from the sky peers the microscopic midget of a Boche plane: he sees a tree—but it may be a gun: he sees a gun—but it may be only a tree. And so the game of hide and seek goes on, in a steady acceleration of ingenuity on both sides, till at last the only logical outcome will be to have no camouflage at all. You will simply put out your big guns fair and square in the open, because nobody will ever believe, by that time, that anything really is what it looks like. As far as the guns go, the war is developing into a colossal fancy dress ball, with immunity for the prize: wolves in sheep’s clothing are nothing to these gentle shepherdesses of the countryside. The more important they are, the more meekly do they shrink from notice under dominos of boughs or sods, or strawberry-netting tagged over with fluffets of green and brown rags. And sometimes they lurk under some undiscoverable knoll in a coppice, and do their barking through a little hole from which you would only expect rabbits, not shells..

And, of course, this fun sense of his [the individual] has full play in this new warfare. It is all “I spy,” on terms of life and death: the other fellow must not spy, or you hear of it instantly, through your skull. Think how it must sharpen up the civilization-sodden intelligence of a man, to have to depend for dear life on noticing every movement in a bush and every opening in a bank. Now we are getting back with one hand what we had lost by giving up the other to machinery. We are growing to make the best of both worlds, the mechanical and the human, without giving up our mental balance by relying exclusively on either. I only wish I could give you an idea of the devices and ingenuities that these grown-up hide-and-seekers have elaborated. All sorts of ludicrously simple things, the more ludicrously simple the better

Every blank-faced trench rampart of sandbags has its hidden eyes—eyes perfectly wide awake all the time, and winking at you wickedly with a rifle. But for your life you could not spot them, until you had had weeks of training, and learned the real meaning of every tiny unevenness or discoloration or bit of darkness. And even then you have to learn to guess which of these is harmless—so as to blind the others with your own fire. Or there is an innocent, untidy, earthy bank, a dump of old boots and tins and bottles and teapots without spouts. But any one of those forlorn oddments may also be the eyelid of a rifle. Only you do not know which—until you have found out! In the beginning of the war you did not find out. Everything was neat and tidy and civilized and well arranged: so you merely got killed.

I’ve quoted this at length because it seems such a radically different view of the new geometries of the First World War to that taken (as I noted here) by Charles Nevinson in his early paintings of the Western Front – at least in its celebratory temper. And yet, in its acknowledgement of the entanglements of the machine and the human, it’s also subversively the same. (Not surprisingly, both Isla and the author of the blog – Roy Behrens, who also wrote the book Camoupedia (2009) – pay close attention to camouflage artists, and there’s also a brief blog post on Camouflage as Futurism that notes Nevinson’s work).

All of this is on my mind today for two reasons. The first is that Farrer’s letter was published in part under the title ‘Hide and Seek‘, which is also the title of a brilliant book on camouflage I’ve belatedly discovered (perhaps that’s appropriate): Hanna Rose Shell, Hide and Seek: Camouflage, Photography and the Media of Reconnaissance, published by the ever -inventive Zone Books in March last year. The more books I buy from Zone, the more I realise that this is a wonderful platform for books that depend on images – not surprising since they are edited by Jonathan Crary,Michel Feher, Hal Foster and Ramona Nadaff.

You can get a sense of Hanna’s (early) work from this essay, ‘The crucial moment of deception’, in Cabinet. There’s also an excellent article on her work in the Paris Review here , another at rhizome here, and a short interview with Hanna here:

The main focus of my book is on the period between the late 19th century and World War II, but I also show how photographic camouflage is present in military research today. What I call an enduring “chameleonic impulse” continues to motivate military R&D of wearable camouflage technologies. There is also an ongoing quest to develop “invisible cloaks” to serve simultaneously as skins and … screens onto which one’s visual environment might be projected.

Many times, people’s first association with camouflage is with the natural world — it’s often the story of the evolution of the “peppered moth” that schoolchildren learn in biology class. But it’s only when humans had to hide from the camera and other optical devices that animal protective concealment began to fascinate people … and then became a model for the development of new human technologies.

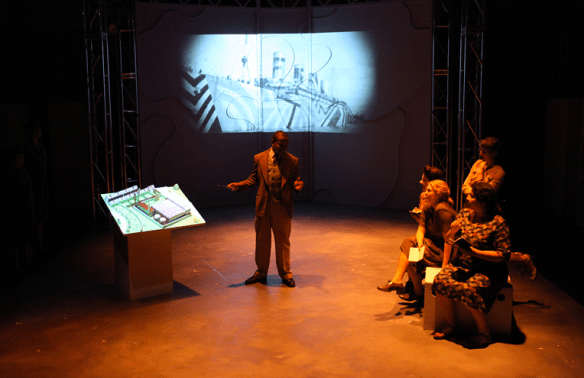

There’s a second reason. I’m presently developing a performance work, provisionally called “The social life of bombs“, where I want (among other things) to integrate the performing and visual arts into the research process (as part of my Killing Space project). My inspiration is in part Gerry Pratt’s Nanay, but more proximately Boca del Lupo‘s Photog, based on the experiences of four combat photographers and using cutting-edge visual technologies to mesmerising effect (I’m going to talk with them next month), and in part Ohio State University’s The Camouflage Project (above). The project involved OSU’s Department of Theater and the Mershon Center for International Security Studies:

The goal of The Camouflage Project is to create, organize and execute a three-part interdisciplinary endeavor linked to the theme of secret agents, camouflage, deception and disguise in World War II, specifically the F section (France) of the Special Operations Executive (SOE). The three parts are as follows:

Performance: To devise a new performance work as a collaboration between Ohio State University Theatre and the Advanced Computing Center for the Arts and Design (ACCAD). This will be a multi-media work combining digital animations and video projections with experimental use of 3D printing, 3D scanning and projection mapping.

Exhibition: To create a visual environment parallel to the performance space, which will have a second life as an installation/exhibition. The installation will feature historical background (interviews and soldier training films) on the science and art of camouflage in both World Wars organized around a visual study of selected SOE (principally female) agents and espionage circuits in France, examples of military equipment, devices, disguises, gadgets and weapons of deception.

Symposium: To organize and host an international symposium on the multiple artistic and instrumental meanings of camouflage, to be held in May 2011. The symposium will feature panels of Ohio State and international experts from military history, political science, and the Imperial War Museum addressing the subject of camouflage and the SOE.

The project offers a fresh meaning to the expression ‘theatre of war.’ On one level it theatricalizes the history of military camouflage, particularly the SOE and the role played by women agents in its espionage activity. On another it reveals the artistic dimensions of these activities: a variety of theatre artists—scenic, costume, make-up designers, and vaudeville magicians—were employed to use their theatrical skills to deceive and fool the enemy. Rather than tales of derring-do and spying, this project seeks to look at different and often hidden aspects of the war: the use and creation of camouflage, both literally and metaphorically, by people who had to work secretly behind enemy lines. The performance storyline will highlight the work of women agents, many of whose accomplishments have been concealed, erased or obscured for a variety of reasons. A narrative strategy will be to include elements of the training process involved in preparing agents for the field and the often-disastrous consequences of strategic decisions made by the SOE leadership.

This all came together in May 2011, though the performance work has subsequently been on tour; the programme for the symposium and performance is here, a review of the 90-minute performance here. My subject is different, of course, but I’m really taken by the tripartite structure of the project and its collaborative nature. Perhaps I have nothing to say, only to show…