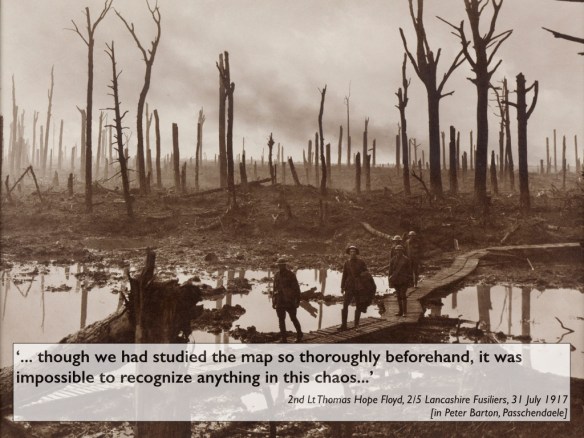

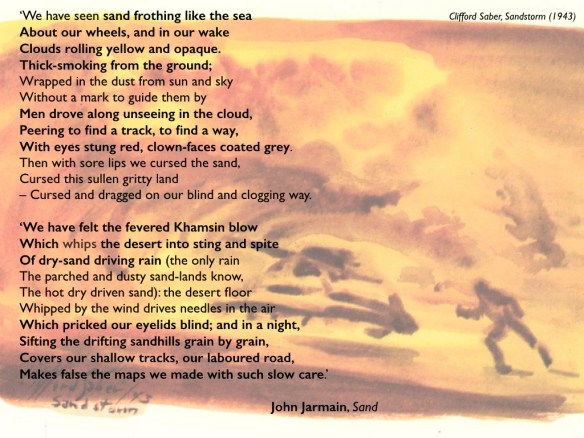

This is far more than a post-script to my last post. In writing ‘The Natures of War’ I started to develop the concept of a corpography (see also ‘Corpographies’ DOWNLOADS tab) because I became keenly interested in the ways in which the entanglements between military violence and ‘nature’ were registered on and through the body.

I had an appreciative message from Eileen Rositzka, following my Neil Smith Lecture at St Andrews, and I’ve finally caught up with a marvellous, exquisitely illustrated essay she has co-written with Robert Burgoyne: ‘Goya on his Shoulder: Tim Hetherington, Genre Memory, and the Body at Risk.’ It was published in Frames Cinema Journal 7 (2015) and is available open access here.

The figure of the body in narratives of war has long served to crystallize ideas about collective violence and the value or futility of sacrifice, often functioning as a symbol of historical transformation and renewal or, contrastingly, as a sign of utter degeneration and waste. As a number of recent studies have shown, the power of somatic imagery to shape cultural perceptions of war has had a decisive impact on the way wars have been regarded in history, and has sometimes influenced the conduct of war as it unfolds.

Following my good friend Gastón Gordillo‘s exemplary lead, I’ve been thinking about extending my original analysis from the mud of the Western Front in the First World War, the deserts of North Africa in the Second, and the rainforests of Vietnam into Afghanistan (for the book-version of the essay), and ‘Goya on his shoulder’ is full of all sorts of ideas on how to do exactly that. Gastón has made much of Sebastian Junger/Tim Hetherington‘s extraordinary film Restrepo – see here and especially here – and Robert and Eileen add all sorts of insights to the mix and, in particular, provide an illuminating visual genealogy of the issues at stake:

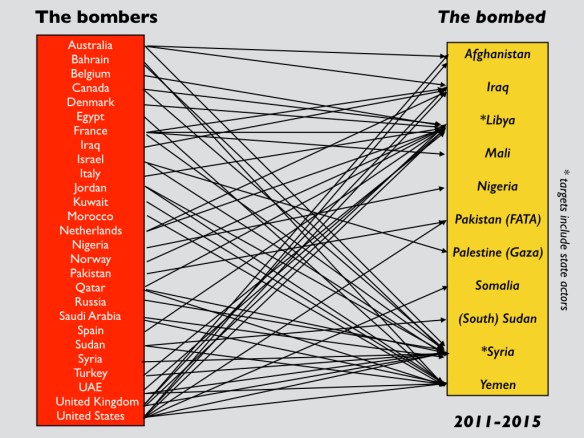

With their concentrated focus on the body in war, Restrepo and Infidel also mark an intervention into contemporary debates in the emerging doctrine of “bodiless war” or virtual war – what is known in war policy circles as the “Revolution in Military Affairs” (RMA). In contrast to the decorporealised, bloodless war culture promoted and even celebrated in many contemporary theories of war, Restrepo and Infidel implicitly dramatise the limitations of so called “optical war” in many current conflict zones, emphasising the body of the soldier as a critical site of representation and meaning.

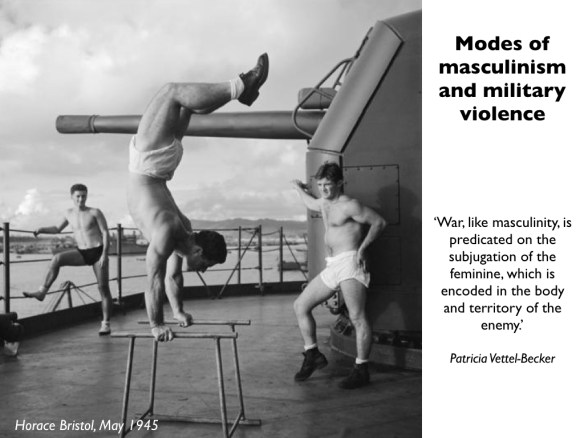

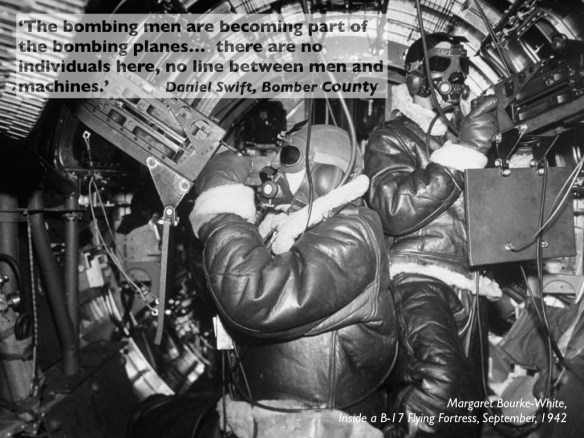

Their journey takes them from photography of the American Civil War through Edward Steichen‘s mesmerising project to capture what they call ‘bodies at risk’ in the Pacific theatre of the Second World War to Afghanistan today. As it happens, I’ve spent the last several weeks immersed in Steichen’s project for my ‘Reach from the skies’ lectures: Steichen was one of the foremost architects of aerial photography on the Western Front during the First World War, and the photographs taken of US sailors taken under his direction during the Second have much to show us about the entanglements between military violence, masculinism and the body (the slide below is taken from my discussion in ‘Reach from the sky’).

And so to Restrepo:

‘… the work of Hetherington and Junger marks an intervention in the contemporary cultural imaginary of war, dramatizing the limitations of so called “optical war” or “bodiless war” in the conflict zones of Afghanistan. The concentrated attention to the touchscape of modern war in their work, moreover, provides a fresh perspective on older traditions of visual representation, illuminating the genre codes of war photography and film in a new way. The visual and acoustic design of Restrepo, in particular, captures the haptic geography of combat in a remote mountain outpost in the Korengal Valley. The film highlights the concentrated experience of sound and touch, providing a first-person account of the way the body inhabits contested space, the way the intensities of war confuse and overwrite the sensory codes of vision, and the compensatory drive of somatic mastery, which is projected in vivid displays of masculine athleticism in the relative safety of the enclosure.

What Steichen called “the machinery of war” is all but absent in these images. Like Steichen, Hetherington expresses the brotherhood of the men in directly physical, gestural forms – in close physical contact, in the “bloodying” of new men, and in the tattoos they give each other with a tattoo gun they have brought up to the camp…

Depictions of war in Restrepo and Infidel revolve around touch – the heat, cold, and dirt, the intense exertion, the texture of skin. Although Hetherington’s images of white, muscular soldiers may be compared to the displays of imperial masculinity celebrated by Edison in his War-Graph actualities, and by Roosevelt in his appeal to the brave “game boys” of military adventure, they also relay the heightened sensuality of Steichen’s World War II sailors to a contemporary war setting. Scenes that contain a high quotient of violence – the firefights with insurgents, the roughhousing, the bloodying of new recruits – are here juxtaposed with shots of soldiers sleeping and other scenes of quiet reflection…

Foregrounding the body of the soldier as a medium of sensory experience and as a body at risk, their work recalls the long history of war photography, painting, and film, dramatizing the importance of the figure of the body in narratives of war, and the power of somatic imagery to shape cultural perceptions of conflict. In Restrepo and Infidel, haptic experience and embodied vulnerability unfold as the central fact of war, the heart of warfare. Here too, however, a certain cultural imaginary is invoked, visible in Junger’s discussion of “young men in war” and of the “hard wiring” of young men for the violence of war, a theme that sacrifices any consideration of context, as if war was an existential constant. Nonetheless, in this framing of contemporary western war, centred on the haptic geography of combat, we can see an initial sketch, an introduction, to a critical understanding of the corpography of war in the current period.

My extracts don’t do justice to the range and depth of the essay, and it really does repay close reading.