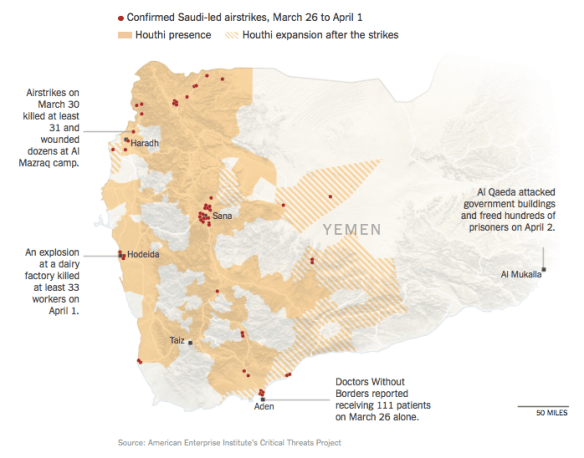

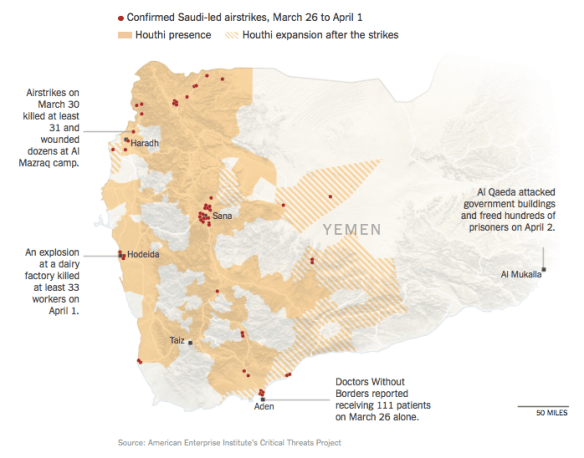

It’s not easy to keep track of the intensifying civil war/proxy war in Yemen, but the New York Times has published a series of maps – including the one below – that sketch out some of the contours of violence.

Not surprisingly, the Saudi-led air strikes (‘Operation Decisive Storm’ – really) have been ineffective in halting the advance of the Houthis; in fact, they may be counterproductive. Three days ago senior United Nations officials warned that the loss of civilian lives and the repeated attacks on civilian infrastructure may constitute grave violations of international law, and there are now reports that US officials are also becoming alarmed at the mounting toll of civilian casualties.

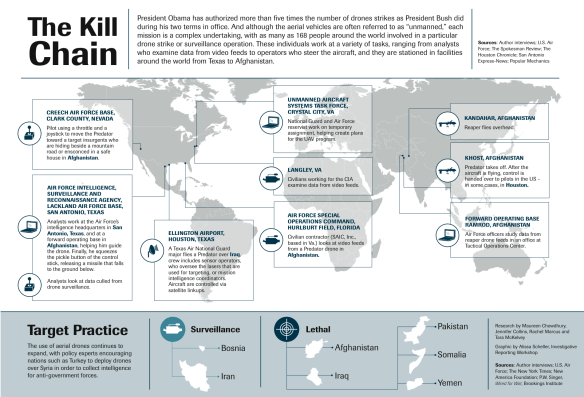

The United States is, of course, intimately involved in the air campaign. According to the Los Angeles Times:

Pentagon officials, who pride themselves on the care they take to avoid civilian casualties, have watched with growing alarm as Saudi airstrikes have hit what the U.N. this week called “dozens of public buildings,” including hospitals, schools, residential areas and mosques. The U.N. said at least 364 civilians have been killed in the campaign.

Although U.S. personnel don’t pick the bombing targets, Americans are working beside Saudi military officials to check the accuracy of target lists in a joint operations center in Riyadh, defense officials said. The Pentagon has expedited delivery of GPS-guided “smart” bomb kits to the Saudi air force to replenish supplies.

The U.S. role was quietly stepped up last week after the civilian death toll rose sharply. The number of U.S. personnel was increased from 12 to 20 in the operations center to help vet targets and to perform more precise calculations of bomb blast areas to help avoid civilian casualties.

U.S. reconnaissance drones now send live video feeds of potential targets and of damage after the bombs hit. The Air Force also began daily refueling flights last week to top off Saudi and United Arab Emirates fighter jets in midair, outside Yemen’s borders, so they can quickly return to the war.

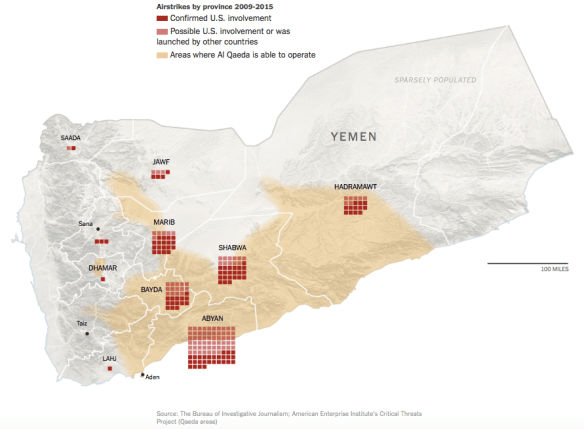

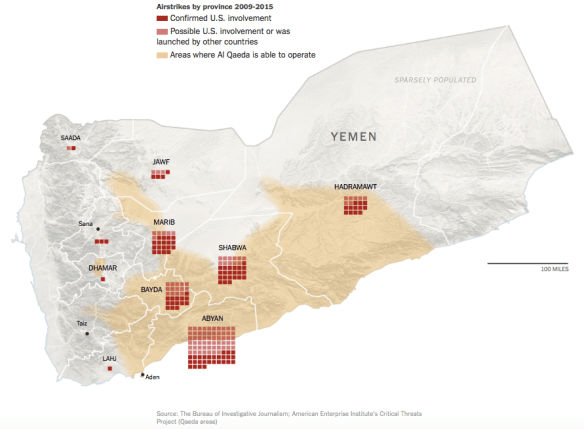

You could be forgiven for thinking this a bit rich. The US has long been waging its own air campaign in Yemen:

The NYT map above is derived from the vital work of the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, and you can find its detailed accounting of drone strikes in Yemen here. Drone strikes have not been suspended during the new air offensive: earlier this week Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula announced that one of its most prominent spokesmen and clerics, Ibrahim al-Rubeish, had been killed by a US drone strike near the coastal city of al Mukalla.

Readers will know that there has been considerable critical discussion of civilian casualties caused by the programme of targeted killing in Yemen (and elsewhere): so much so that on 23 May 2013 the Obama administration issued a Presidential Policy Guidance [PPG] for the use of force ‘outside the United States and areas of active hostilities’ that supposedly imposed more stringent restrictions on its use of (para)military violence outside ‘hot battlefields’ like Afghanistan.

The guidelines affirmed a preference for ‘capture’ over ‘kill’ – ‘The policy of the United States is not to use lethal force when it is feasible to capture a terrorist suspect, because capturing a terrorist offers the best opportunity to gather meaningful intelligence and to mitigate and disrupt terrorist plots’ – and so limited the use of lethal force to situations where ‘capture is not feasible at the time of the operation‘. That last clause –my emphasis – clearly provides wide latitude for elevating ‘kill’ over capture’, but for a recent, vigorous discussion of the kill/capture debate prompted by the arrest and indictment of Mohanad Mahmoud Al Farekh earlier this month, see David Cole on ‘Targeted killing’ here.

The guidelines affirmed a preference for ‘capture’ over ‘kill’ – ‘The policy of the United States is not to use lethal force when it is feasible to capture a terrorist suspect, because capturing a terrorist offers the best opportunity to gather meaningful intelligence and to mitigate and disrupt terrorist plots’ – and so limited the use of lethal force to situations where ‘capture is not feasible at the time of the operation‘. That last clause –my emphasis – clearly provides wide latitude for elevating ‘kill’ over capture’, but for a recent, vigorous discussion of the kill/capture debate prompted by the arrest and indictment of Mohanad Mahmoud Al Farekh earlier this month, see David Cole on ‘Targeted killing’ here.

In addition, crucially, the PPG required there to be a ‘near certainty’ that civilians would not be killed or injured during the operation.

Yet even when the guidelines were issued, they were ambiguous. As Ryan Goodman pointed out, grey zones remained:

The notion of “areas of active hostilities” essentially refers to geographic zones where belligerents engage in sustained fighting. It is a term of art, as far as we can tell, developed by the administration at an unknown date, and not found in international law. In congressional testimony, the administration has stated that it considers Afghanistan an area of active hostilities, and it considers Yemen (despite frequent drone operations in that country) and Somalia outside the area of active hostilities.

These topological contortions did not begin with Obama. The Bush administration made no secret of its central interest in ‘conducting war in countries we are not at war with‘.

Ryan’s discussion focused on the ambiguous location of Pakistan in this atlas of violence, and in particular the Federally Administered Tribal Areas: were they inside or outside “areas of active hostilities” (or even ‘half-in, half-out’)? Since then, clearly, Yemen too may have been repositioned by Obama’s cartographers: it’s surely difficult to maintain the pretence that it is now not an ‘area of active hostilities’.

But in between the PPG and the opening of the new air offensive in Yemen, how effective were those restrictions on civilian casualties? A collaborative investigation carried out by the Open Society Justice Initiative in the United States and the Mwatana Organization for Human Rights in Yemen raises plausible doubts.

Their joint report, Death by Drone: civilian harm caused by targeted killing in Yemen, investigates nine US air strikes carried out between May 2012 and April 2014, and is based on interviews with survivors and eyewitnesses, relatives of individuals killed or injured in the attacks, local community leaders, doctors and hospital staff who were involved in the treatment of victims, and Yemeni government officials:

The nine case studies documented in this report provide evidence of 26 civilian deaths and injuries to an additional 13 civilians. This evidence casts doubt on the U.S. and Yemeni governments’ statements about the precision of drone strikes. Yemen’s President Abdu Rabbu Mansour al-Hadi praised U.S. drone strikes in Yemen as having a “zero margin of error” and commented that “the electronic brain’s precision is unmatched by the human brain.” The United States government has similarly emphasized that the precision afforded by drone technology enables the U.S. to kill al-Qaeda terrorists while limiting civilian harm…

[T]his report provides credible evidence that civilians were killed and/or injured in all nine airstrikes, including four which post-date President Obama’s [PPG] speech. To be sure, it is possible—owing to a mistake or an unforeseeable change of circumstances that manifests between the ordering of a strike and its occurrence—for civilians to be killed or injured despite a near-certainty prior to the strike that this would not happen. Nonetheless, the evidence of civilian deaths and injuries in nine cases raises serious concerns about the effective implementation of the “near-certainty” standard.

And in paragraphs that will be dismally familiar to anyone who has read the Stanford/NYU report on Living under drones in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas, the authors add:

The testimonies in this report describe desperately poor communities left to fend for themselves amid the devastation caused by U.S. drone strikes. Mothers and fathers who lost their children in drone strikes speak of inconsolable loss. They speak of their children’s bodies charred beyond recognition. Wives speak of losing their breadwinners, and of young children asking where their fathers have gone. The victims of these strikes say that these strikes will not make the United States or Yemen safer, and will only strengthen support for al-Qaeda.

The report also describes the terrorizing effects of U.S. drones on local populations. In many of the incidents documented, local residents had to live with drones continually flying overhead prior to the strikes and have lived in constant fear of another attack since. Some fled their villages for months after the strike, and lost their source of livelihood in the process. Survivors of the attacks continue to have nightmares of being killed in the next strike. Men go to their farms in fear. Children are afraid to go to school.

The Executive Summary is here, and you can download the full 123pp report here.

Just back from the AAG in Chicago, where I picked up a pre-publication copy of Nick Turse‘s new book, Tomorrow’s Battlefield: US proxy wars and secret ops in Africa (Haymarket) (and I have to say it was a relief to see Haymarket and Verso after the depressing parade of textbooks that dominated the publishers’ exhibition).

Just back from the AAG in Chicago, where I picked up a pre-publication copy of Nick Turse‘s new book, Tomorrow’s Battlefield: US proxy wars and secret ops in Africa (Haymarket) (and I have to say it was a relief to see Haymarket and Verso after the depressing parade of textbooks that dominated the publishers’ exhibition).