I’m just back from a wonderful time at a conference in Galway organised by John Morrissey as part of The Haven Project on the refugee crisis in the Mediterranean. The latest issue of Human Geography (Vol 9, No 2) is devoted to Geographical Perspectives on the European ‘Migration and Refugee Crisis‘ – those scare-quotes are vital – and if your library doesn’t subscribe you can contact the Institute of Human Geography at insthugeog@gmail.com (most of the articles can be downloaded here).

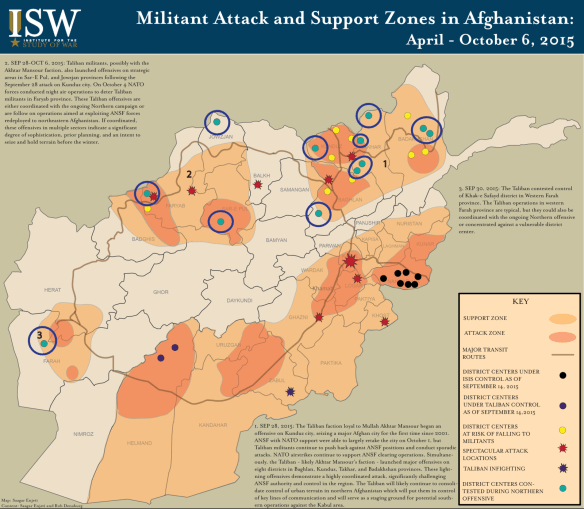

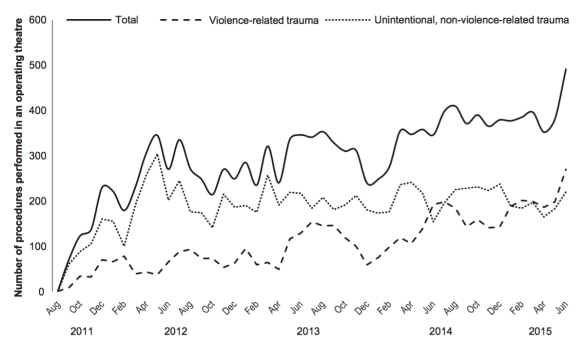

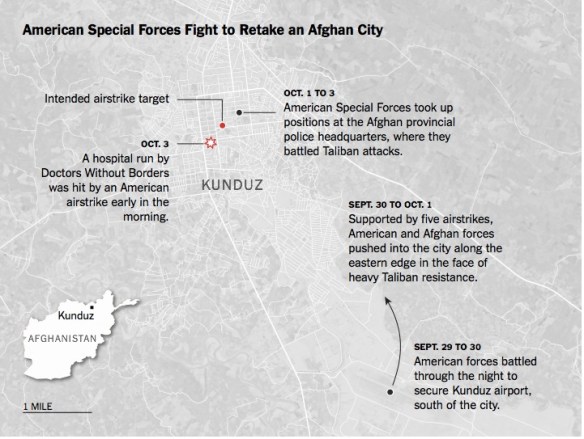

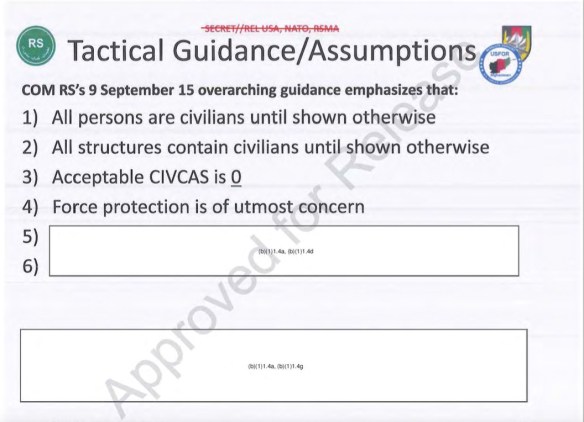

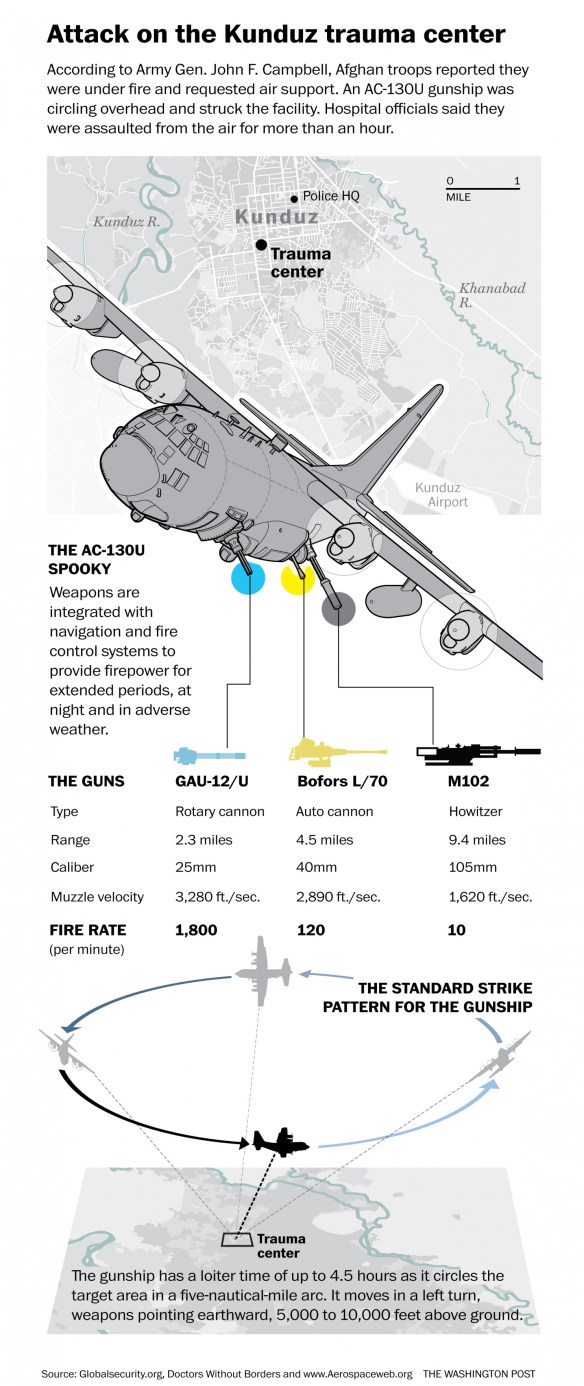

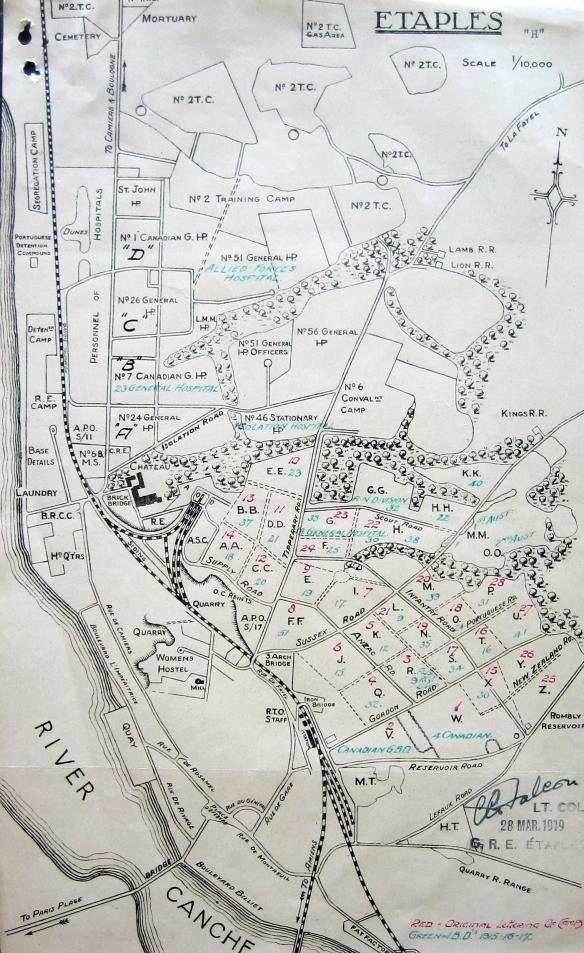

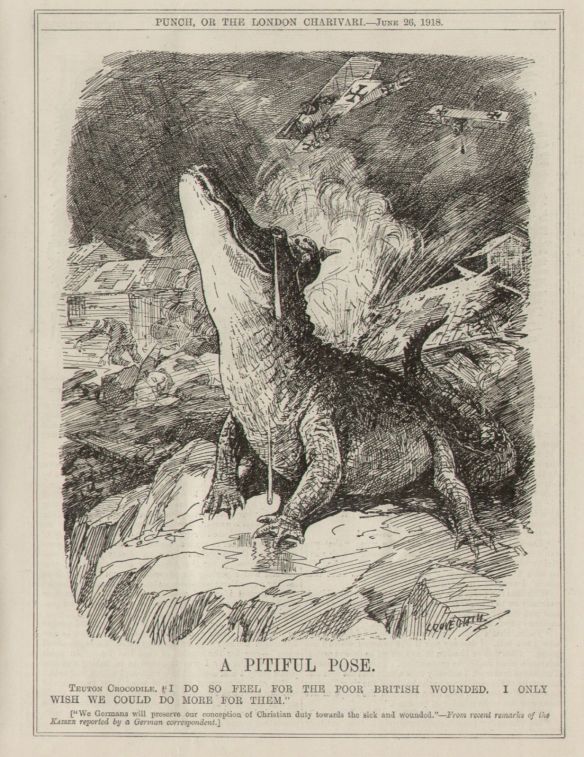

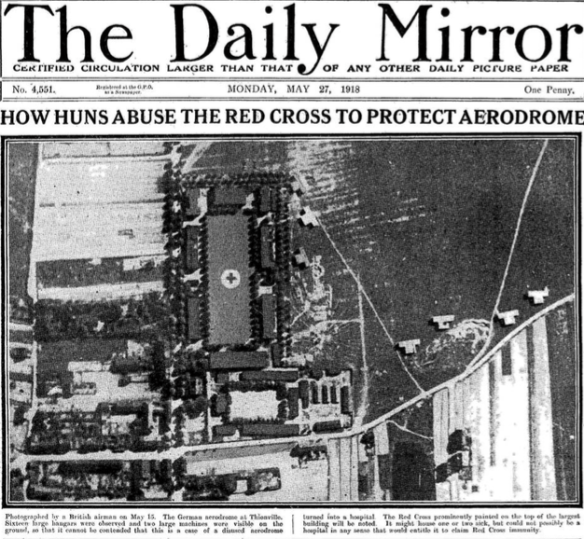

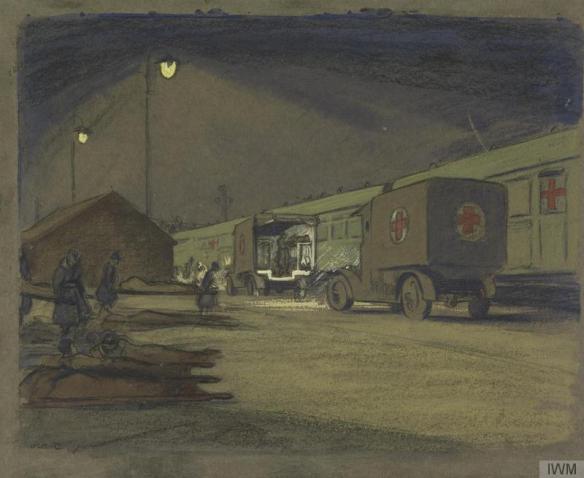

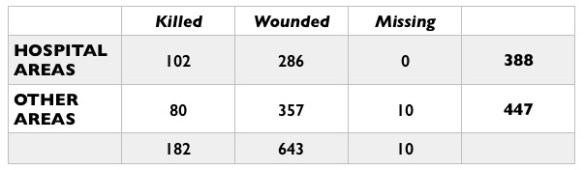

At Galway I gave a new presentation on ‘Surgical strikes and modern war’, describing and analyzing the ways in which hospitals and ambulances, doctors and nurses have become targets of military violence; it drew on my new series of posts (see here and here), and there will be more to come on both Kunduz and on Syria (which was my main focus), but you can find a preliminary account of the whole event from Alex Jeffrey here.

My starting point was the modern space of exception seen not as ‘the camp‘, as Giorgio Agamben would have it, but as the killing fields of contemporary military and paramilitary violence (what would once have been called ‘the battlefield‘). For these are spaces in which groups of people are knowingly and deliberately exposed to death through the removal of legal protections that would ordinarily be afforded them; and yet these are not spaces in which the law is suspended tout court, spaces from which the law withdraws and abandons the victims of violence to their fate, but rather spaces in which law – and specifically international humanitarian law – seeks to regulate and, crucially, to sanction violence. This is a form of martial law that Agamben never considers (I know I am taking liberties with that term, but that is precisely my point): here as elsewhere violence exists not only beyond the law but is inscribed within it. My purpose was to show how what was once a sacred space within this zone of exception – ‘the hospital’, a topological figure that extends from the body of the wounded through the sites of the evacuation chain to the hospital itself – has become corroded; no longer a space of immunity – of safety – an exception to the exception, it has often become a central target of contemporary violence.

The need to pull all this together largely explains my silence these last weeks, and a lot has happened in the interim. Where to start? A good place is the latest issue of Radical Philosophy, the last in its present form, which includes two essays of direct relevance to the theme of the Galway conference.

First, an important essay by Achille Mbembe on ‘The Society of Enmity’ which you can download here:

Desire (master or otherwise) is also that movement through which the subject – enveloped on all sides by a specific phantasy [fantasme] (whether of omnipotence, ablation, destruction or persecution, it matters little) – seeks to turn back on itself in the hope of protecting itself from external danger, while other times it reaches outside of itself in order to face the windmills of the imagination that besiege it. Once uprooted from its structure, desire then sets out to capture the disturbing object. But since in reality this object has never existed – does not and will never exist – desire must continually invent it. An invented object, however, is still not a real object. It marks an empty yet bewitching space, a hallucinatory zone, at once enchanted and evil, an empty abode haunted by the object as if by a spell.

The desire for an enemy, the desire for apartheid, for separation and enclosure, the phantasy of extermination, today all haunt the space of this enchanted zone. In a number of cases, a wall is enough to express it. There exist several kinds of wall, but they do not fulfil the same functions. [6] A separation wall is said to resolve a problem of excess numbers, a surplus of presence that some see as the primary reason for conditions of unbearable suffering. Restoring the experience of one’s existence, in this sense, requires a rupture with the existence of those whose absence (or complete disappearance) is barely experienced as a loss at all – or so one would like to believe. It also involves recognizing that between them and us there can be nothing that is shared in common. The anxiety of annihilation is thus at the heart of contemporary projects of separation.

Everywhere, the building of concrete walls and fences and other ‘security barriers’ is in full swing. Alongside the walls, other security structures are appearing: checkpoints, enclosures, watchtowers, trenches, all manner of demarcations that in many cases have no other function than to intensify the zoning off of entire communities, without ever fully succeeding in keeping away those considered a threat.

You can already surely hear the deadly echoes of Carl Schmitt – whose spectral presence lurked in the margins of my own presentation in Galway (for geographical elaborations of Schmitt, see Steve Legg‘s Spatiality, sovereignty and Carl Schmitt and Claudio Minca and Rory Rowan‘s On Schmitt and space) – and Achille makes the link explicit:

This is an eminently political epoch, since ‘the specific political distinction’ from which ‘the political’ as such is defined – as Carl Schmitt argued, at least – is that ‘between friend and enemy’. If our world today is an effectuation of Schmitt’s, then the concept of enemy is to be understood for its concrete and existential meaning, and not at all as a metaphor or an empty lifeless abstraction. The enemy Schmitt describes is neither a simple competitor, nor an adversary, nor a private rival whom one might hate or feel antipathy for. He is rather the object of a supreme antagonism. In both body and flesh, the enemy is that individual whose physical death is warranted by their existential denial of our own being.

However, to distinguish between friends and enemies is one thing; to identify the enemy with certainty is quite another. Indeed, as a ubiquitous yet obscure figure, today the enemy is even more dangerous by being everywhere: without face, name or place. If they have a face, it is only a veiled face, the simulacrum of a face. And if they have a name, this might only be a borrowed name, a false name whose primary function is dissimulation. Sometimes masked, other times in the open, such an enemy advances among us, around us, and even within us, ready to emerge in the middle of the day or in the heart of night, every time his apparition threatening the annihilation of our way of life, our very existence.

Yesterday, as today, the political as conceived by Schmitt owes its volcanic charge to the fact that it is closely connected to an existential will to power. As such, it necessarily and by definition opens up the extreme possibility of an infinite deployment of pure means without ends, as embodied in the execution of murder.

The essay is taken from Achille’s latest book, Politiques de l’inimitié published by Découverte in 2016:

Introduction – L’épreuve du monde

1. La sortie de la démocratie

Retournement, inversion et accélération

Le corps nocturne de la démocratie

Mythologiques

La consumation du divin

Nécropolitique et relation sans désir

2. La société d’inimitié

L’objet affolant

L’ennemi, cet Autre que je suis

Les damnés de la foi

État d’insécurité

Nanoracisme et narcothérapie

3. La pharmacie de Fanon

Le principe de destruction

Société d’objets et métaphysique de la destruction

Peurs racistes

Décolonisation radicale et fête de l’imagination

La relation de soin

Le double ahurissant

La vie qui s’en va

4. Ce midi assommant

Impasses de l’humanisme

L’Autre de l’humain et généalogies de l’objet

Le monde zéro

Anti-musée

Autophagie

Capitalisme et animisme

Émancipation du vivant

Conclusion. L’éthique du passant

Second, an essay by Mark Neocleous and Maria Kastrinou, ‘The EU hotspot: Police war against the migrant’, which you can download here. They start by asking a series of provocative questions about the EU strategy of ‘managing’ (read: policing) migration through the designation of ‘hotspots’ in which all refugees are to be identified, registered and fingerprinted:

There is no doubt that in some ways the term ‘hotspot’ is meant to play on the ubiquity of this word as a contemporary cultural trope, but this obviousness may obscure something far more telling, something not touched on by the criticisms of the hotspots, which tend to focus on either their squalid conditions or their legality (for example, with routes out of Greece being closed off migrants are in many ways being detained rather than registered; likewise, although ‘inadmissibility’ is being used as the reason to ship migrants back to Turkey, in reality ‘inadmissibility’ often means nothing other than that the political and bureaucratic machine is working too slowly to adequately process asylum claims). Neither the legality nor the sanitary state of the hotspot is our concern here. Nor is the fact that the hotspots use identification measures largely as instruments of exclusion. Rather, we are interested in what the label ‘hotspot’ might tell us about the way the EU wants to manage the crisis. What might the hotspot tell us about how the EU imagines the refugee? But also, given that the EU’s management of the refugee crisis is a means for it to manage migration flows across Europe as a whole, what might the hotspot tell us about how the EU imagines the figure of the migrant in general?

You can find an official gloss (sic) on hotspots here (and more detail here), critical readings by Frances Webber here and Glenda Garelli and Martina Taziolli here, and NGO responses from Oxfam here and Caritas here. The Bureau of Investigative Journalism also has a useful report on Frontex, the EU’s border agency, here.

Here is the kernel of Mark’s and Maria’s answer to their questions – and you will see see the link with Achille’s essay immediately:

For every police war, an enemy is needed. Defining the zones as hotspots suggests that migrants have arrived as somehow already ‘illegal’ in some way, enabling them to be situated within the much wider and never-ending ‘war on crime’. Yet this process needs to be understood within the wider practice of criminalizing breaches of immigration law in western capitalist polities over the last twenty years, as individual states and the state system as a whole have increasingly sought to make the criminal law work much more closely with immigration law: ‘crimmigration’, as it has become known, means that criminal offences can now very easily result in deportation, while immigration violations are now frequently treated as criminal offences. Concerning the UK, for example, Ana Aliverti has noted that ‘the period between 1997 and 2009 witnessed the fastest and largest expansion of the catalogue of immigration crimes since 1905’. This expansion serves to further reinforce the conception of the migrant as already tainted by crime, as the figure of the criminal and the figure of the migrant slowly merge. The term ‘illegal immigrant’ plays on this connection in all sorts of ambiguous ways. Indeed, it is significant that the very term ‘illegal immigrant’ has over the same period replaced the term ‘undocumented migrant’, so that a figure once seen as lacking papers is seen now as lacking law.

However, the fact that migrants arriving in the EU hotspots do so as propertyless (or at least apparently so) subjects adds a further significance. Why? Because by arriving propertyless the historical figure to which the migrant is most closely aligned is as much the vagrant as the criminal. Aliverti’s reference to 1905 is a reference to the Aliens Act of that year, in which any ‘alien’ landing in the UK in contravention of the Act was deemed to be a rogue and vagabond. The Act was underpinned by making such ‘aliens’ liable to prosecution under section 4 of the Vagrancy Act of 1824, usually punishable in the form of hard labour in a house of correction. As Aliverti puts it, ‘in view of the similarities between the poor laws and early immigration norms, it is no coincidence that the first comprehensive immigration legislation in 1905 penalized the unauthorized landing of immigrants with the penalties imposed on “rogues and vagabonds” and vagrancy was one of the grounds for expulsion of foreigners.’ In the mind of the state, the vagrant is the classic migrant, just as migrants arriving in the hotspots are increasingly coming to look like and be treated as the newest type of vagrant. In the mind of the state, the propertyless migrant is a kind of vagrant-migrant (which is of course one reason why welfare and migration are so frequently connected).

Vagrancy legislation has always been the ultimate form of police legislation: it criminalizes a status rather than an act (the offence of vagrancy consists of being a vagrant); it gives utmost authority to the police power (the accusation of vagrancy lies at the discretion of the police officer); and it seeks not to punish a crime as such but to instead eliminate what are regarded as threats to social order (as in section 4 of the UK’s Vagrancy Act of 1824, which enables people to be arrested and punished for being ‘idle and disorderly’, for ‘being a rogue’, for ‘wandering abroad’ or for simply ‘not giving a good account of himself or herself’; note the present tense used – section 4 of the Act of 1824 is still in operation in the UK).

And in case the links with ‘The society of enmity’ are still opaque, I leave the last word to Achille:

Hate movements, groups invested in an economy of hostility, enmity, various forms of struggle against an enemy – all these have contributed, at the turn of the twenty-first century, to a significant increase in the acceptable levels and types of violence that one can (or should) inflict on the weak, on enemies, intruders, or anyone considered as not being one of us. They have also contributed to a widespread instrumentalization of social relations, as well as to profound mutations within contemporary regimes of collective desire and affect. Further, they have served to foster the emergence and consolidation of a state-form often referred to as the surveillance or security state.

From this standpoint, the security state can be seen to feed on a state of insecurity, which it participates in fomenting and to which it claims to be the solution. If the security state is a structure, the state of insecurity is instead a kind of passion, or rather an affect, a condition, or a force of desire. In other words, the state of insecurity is the condition upon which the functioning of the security state relies in so far as the latter is ultimately a structure charged with the task of investing, organizing and diverting the constitutive drives of contemporary human life. As for the war, which is supposedly charged with conquering fear, it is neither local, national nor regional. Its extent is global and its privileged domain of action is everyday life itself. Moreover, since the security state presupposes that a ‘cessation of hostilities’ between ourselves and those who threaten our way of life is impossible – and that the existence of an enemy which endlessly transforms itself is irreducible – it is clear that this war must be permanent. Responding to threats – whether internal, or coming from the outside and then relayed into the domestic sphere – today requires that a set of extra-military operations as well as enormous psychic resources be mobilized. The security state – being explicitly animated by a mythology of freedom, in turn derived from a metaphysics of force – is, in short, less concerned with the allocation of jobs and salaries than with a deeper project of control over human life in general, whether it is a case of its subjects or of those designated as enemies.