I’ve used this Buffalo Springfield song before –

there’s something happenin’ here

what it is ain’t exactly clear

there’s a man with a gun over there…

stop, hey, what’s that sound?

– and I’ve posted about the sound of war before too, here and here. This post is connected to both of them, but it also follows directly from my more recent post on bodies…

An age ago Trevor Barnes recommended Tom McCarthy‘s novel C to me, and I’ve been re-reading it these last few days. There’s an extraordinary passage where McCarthy’s protagonist Serge, an observer with the Royal Flying Corps during World War I, is being driven to Nieppe when his truck detours ‘to drop off some piano wire’ to a special unit in the woods north of Vitriers.

An age ago Trevor Barnes recommended Tom McCarthy‘s novel C to me, and I’ve been re-reading it these last few days. There’s an extraordinary passage where McCarthy’s protagonist Serge, an observer with the Royal Flying Corps during World War I, is being driven to Nieppe when his truck detours ‘to drop off some piano wire’ to a special unit in the woods north of Vitriers.

Inside the main [hut], he finds a huge square harp whose six strings are extended out beyond their wooden frame by finer wires that run through the hut’s air before breaching its boundary as well, cutting through little mouse-holes in the east-facing wall. In front of the harp, like an interrogation lamp, a powerful bulb shines straight onto it; behind it, lined up with each string, a row of prisms capture and deflect the light at right angles, through yet another hole cut in the hut’s wall, into an unlit room adjoining this one. There’s a noise coming from the adjoining room: sounds like a small propeller on a stalled plane turning from the wind’s pressure alone. “What is this place?” Serge asks. “You’re an observer, right?” the slender-fingered man says. Serge nods. “Well, you know how, when you’re doing Battery Location flights, you send down K.K. calls each time you see an enemy gun flash?” “Oh yes,” Serge answers. “I’ve always wondered why we have to do that …” “Wonder no more,” the man says with an elfin smile. “The receiving operator presses a relay button each time he gets one of those; this starts the camera in the next room rolling; and the camera captures the sound of the battery whose flash you’ve just K.K.’d to us. You with me?” “No,” Serge answers. “How can it do that?” “Each gun-boom, when it’s picked up by a mike, sends a current down the wires you just pissed on,” the man continues, “and the current makes the piano wire inside this room heat up and give a little kick, which gets diffracted through the prisms into the next room, and straight into the camera.” “So you’re filming sound?” Serge asks. “You could say that, I suppose,” the man concurs.

Still puzzled, he follows the man into another hut:

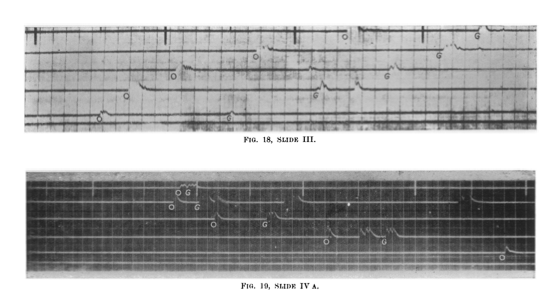

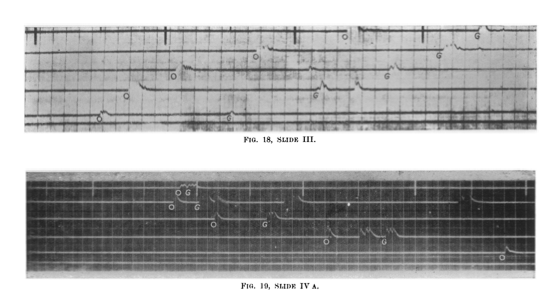

The interior’s suffused with red light. At a trough propped up against the far wall, a man with rolled-up sleeves is dunking yards of film into developing liquid, then feeding it on from there into a fixing tank. As the film’s end emerges from this tank in turn, he holds it up, inspects it and tears off sections, clipping these with clothes pegs to a short stretch of washing line, from where they drip onto the discarded strips on the room’s floor below them. “Yuk,” Serge whispers beneath his breath. “What?” the slender-fingered man asks. “Nothing,” he replies. “Look here,” Serge’s guide says, unclipping a strip of the developed film and pointing at dark lines that run, lengthways and continuous, along its surface. The lines—six of them—are for the most part flat; occasionally, though, they erupt suddenly, and rise and fall in jagged waves, like some strange Persian script, for half an inch, before settling down and running flat again. On the film’s bottom edge, beside the punch-holes, a time-code is marked, one inch or so for every second. The jagged eruptions appear at different points along each line: staggered, each wave the same shape as the one on the line below it, but occurring a quarter of an inch (or three-tenths of a second) later. “So,” Serge’s elfin guide continues, “these kicks are made by the sound hitting each mike; and they get laid out on the film at intervals that correspond to each mike’s distance from the sound. You see them?” “Yes,” Serge answers. “But I still don’t—” “These ones ready to take through?” the guide asks the developer. The other man nods; with his piano-player’s fingers, the guide unclips the other drip-dried strips, then leads Serge out to yet another hut. This one’s wall has a large-scale map taped to it; stuck in the map in a neat semi-circle are six pins. Two men are going through a pile of torn-off, line-streaked film-strips, measuring the gaps between the kicks with lengths of string; then, moving the string over to the map slowly, careful to preserve the intervals, they transfer the latter onto its surface by fixing one end of the string to the pin and holding a pencil to the other, swinging it from side to side to mark a broad arc on the map. “Each pin’s a microphone,” the slender-fingered man explains. “Where the arcs intersect, the gun site must be.” “So the strings are time, or space?” Serge asks. “You could say either,” the man answers with a smile. “The film-strip knows no difference. The mathematical answer to your question, though, is that the strings represent the asymptote of the hyperbola on which the gun lies.”

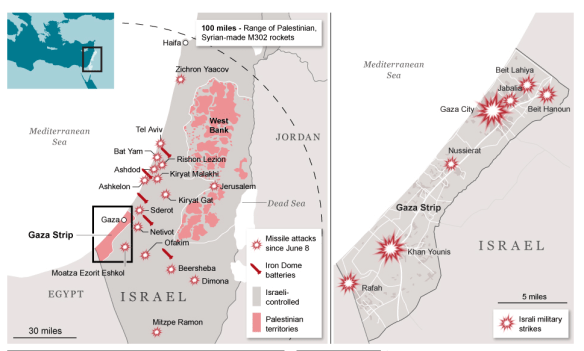

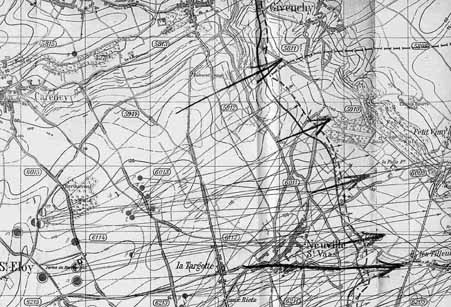

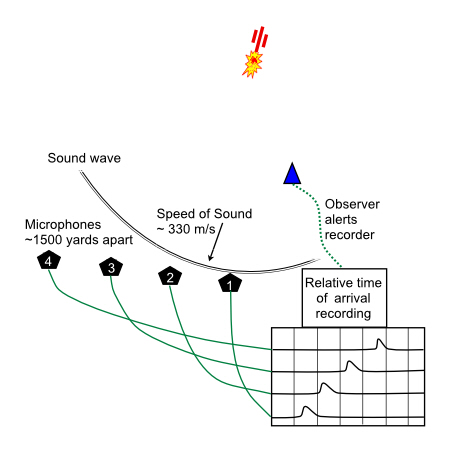

Serge has stumbled into what Peter Liddle called ‘the Manhattan Project of the 1914-18 war’: sound ranging. It was a technique first developed by the French and German militaries – a German sound ranging analysis section is shown below – taken up (warily) by the British (Berton claims their old-school gunners at first thought it radical nonsense) and refined by the Canadians. As McCarthy’s brilliant reconstruction shows, it involved using sound to locate enemy artillery batteries.

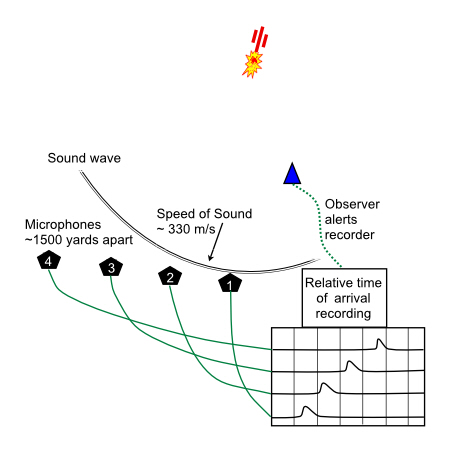

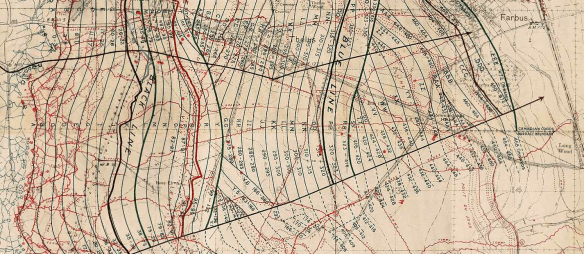

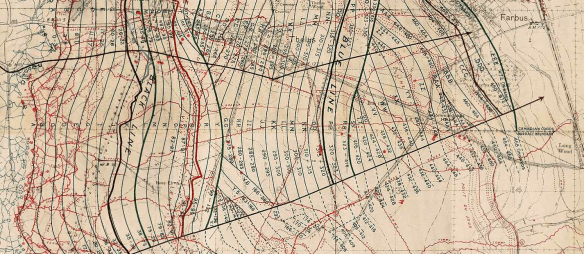

The usual configuration was to have six ‘Tucker’ microphone stations at carefully surveyed intervals along an arc 4000 yards behind the front line with two observation posts in front of them, all linked to a recording station in the rear by 40 miles of wire. When the observers saw a gun flash or heard its boom they sent a signal that activated the oscillograph and film recorder. In the course of 1916 the British established eight of these sound-ranging sections, each plotting battery positions on base maps supplied by ‘Maps GHQ’. In ideal conditions (which were rare) the operation could be completed for a single battery within three minutes (using graphical rather than computational methods) and with an accuracy of 25-100 yards (for more, see J.S. Finan and W.J. Hurley, ‘McNaughton and Canadian Operational Research at Vimy’, Jnl. of the Operational Research Society 48 (1) (1997) 10-14).

The single best source on this – though the title sounds like Flash Gordon – is John Innes‘s Flash spotters and sound rangers: how they lived, worked and fought in the Great War (1935), but Pierre Berton‘s Vimy (1986) has some useful summary pages on the Canadian role in its development. There is also a truly excellent survey that places sound-ranging in the wider context of the ‘battlefield laboratory’ in Roy MacLeod, ‘Sight and sound on the Western Front: surveyors, scientists and the “battlefield laboratory”, 1915-1918’, War & Society 18 (1) (2000) 23-46. For more technical discussions, Peter Chasseaud‘s Artillery’s astrologers: a history of British survey and mapping on the Wester Front 1914-1918 (1999) is a key source, but there is also an exemplary (short) explanation here, from which I’ve borrowed the simplified summary diagram below.

The Germans were evidently impressed by the efficacy of the Allied system, as this directive issued by General Ludendorff shows:

According to a captured English document the English have a well- developed system of sound-ranging which in theory corresponds to our own. Precautions are accordingly to be taken to camouflage the sound: e.g. registration when the wind is contrary, and when there is considerable artillery activity, many batteries firing at the same time, simultaneous firing from false positions, etc. The English have an objective method (self-recording apparatus). It is important to capture such an apparatus. The same holds good on the French front.

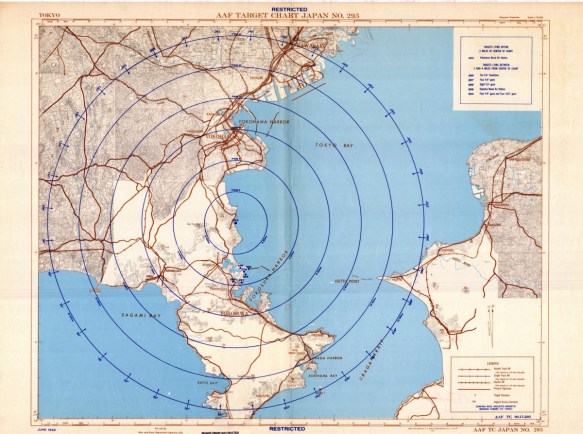

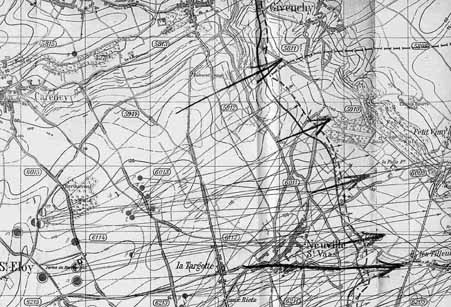

Since most of the killing and destruction was the work of the artillery, these counter-battery operations were a crucial part of the ground war. Multiple sources were used, including aerial reconnaissance, balloon observation and flash spotting as well as sound ranging, and when combined these could eventually locate enemy guns to within 5-25 yards. This map of German artillery intelligence for Vimy in March 1917 shows something of the power and complexity of this ‘acoustic cartography’:

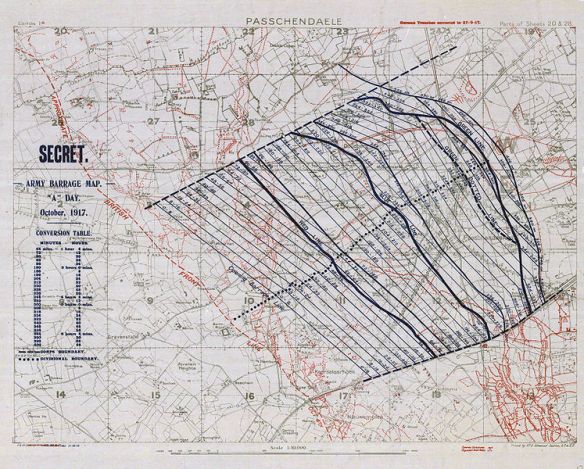

Maps showing the location of enemy batteries (‘Positions maps’ like the British one below) were issued on a regular and eventually even a daily basis.

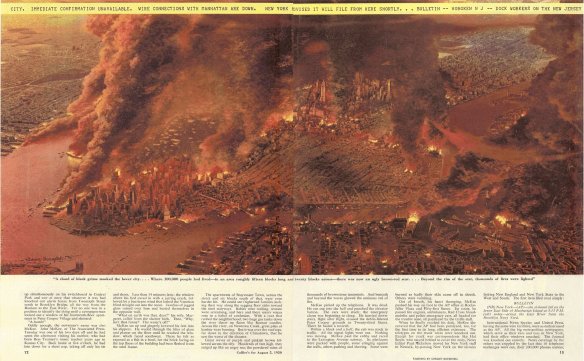

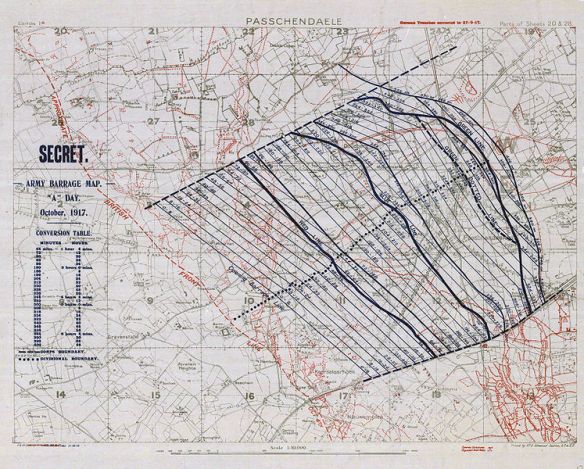

This was all part of a more general metricisation of the battlefield – hideously appropriate for the killing machine that was industrialized warfare – which you can also see in the ‘barrage maps’ that choreographed the moving curtain of artillery fire behind which troops were supposed to advance on the enemy lines. John Keegan is very good on what he called ‘the mathematics of the barrage’ in his The Face of Battle, and from his aircraft high above No Man’s Land, Billy Bishop described it as ‘clockwork warfare’:

The waves of attacking infantry as they came out of their trenches and trudged forward behind the curtain of shells laid down by the artillery, were an amazing sight. The men seemed to wander across No Man’s Land, and into the enemy trenches, as if the battle was a great bore to them. From the air it looked as though they did not realise that they were at war and were taking it all entirely too quietly. That is the way with clock-work warfare. These troops had been drilled to move forward at a given pace. They had been timed over and over again in marching a certain distance, and from this timing the “creeping,” or rolling barrage which moved in front of them had been mathematically worked out.

Here’s part of the barrage map for Vimy, which shows the calibration even more clearly:

McCarthy captures this ‘clockwork’ movement perfectly when Serge looks down from his aircraft while spotting for artillery:

As the second-hand needle moves across the final quarter-segment of his watch’s face, Serge feels an almost sacred tingling, as though he himself had become godlike, elevated by machinery and signal code to a higher post within the overall structure of things, a vantage point from which the vectors and control lines linking earth and heaven, the hermetic language of the invocations, its very lettering and script, have become visible, tangible even, all concentrated at a spot just underneath the index finger of his right hand which is tapping out, right now, the sequence C3E MX12 G … Almost immediately, a white rip appears amidst the wood’s green cover on the English side. A small jet of smoke spills up into the air from this like cushion stuffing; out of it, a shell rises. It arcs above the trench-meshes and track-marked open ground, then dips and falls into the copse beneath Serge, blossoming there in vibrant red and yellow flame. A second follows it, then a third. The same is happening in the two-mile strip between Battery I and its target, and Battery M and its one, right on down the line: whole swathes of space becoming animated by the plumed trajectories of plans and orders metamorphosed into steel and cordite, speed and noise. Everything seems connected: disparate locations twitch and burst into activity like limbs reacting to impulses sent from elsewhere in the body, booms and jibs obeying levers at the far end of a complex set of ropes and cogs and relays. The salvos pause; Serge plots the points of impact on his clock-code chart, then sends adjustments back to Battery E, which fires new salvos that land slightly to the north of the first ones.

There’s a lot more to say about this, which I plan to do in the full presentation, but what interests me at least as much is the way in which this precision (Gabriel’s ‘order and reasonableness’) – so clear and crystalline when plotted on maps or seen from the air – was confounded on the ground, not least by the shattered landscape of craters, trenches and barbed wire and by the vile agency of what Siegfried Sassoon called the ‘plastering slime’ that clawed and dragged at the soldiers’ bodies and which was erased from what Edmund Blunden called the ‘innocuous arrows’ and ‘matter-of-fact symbols’ of the maps and aerial photographs.

More particularly, I’m interested (here) in the production of an altogether more sensuous soundscape, part of the corpography that danced such a deadly gavotte with cartography that I sketched out in my previous post. In Touch and intimacy Santanu Das argues that

‘The mechanised nature of the First World War severed the link between sight, space and danger, a connection that had traditionally been used to structure perception in wartime. This disjunction resulted in an exaggerated investment in sound.’

The memoirs, letters and diaries from the Western Front confirm that the hideous noise of battle worked its way inside the very body of the soldier. I’ve got pages of examples, but here is just one, Edward Lynch in Somme Mud (and, for that matter, in Somme mud):

‘The shells are missing us by a matter of yards. Noise is everywhere. We lie on the shuddering ground, rocking to the vibrations, under a shower of solid noise we feel we could reach out and touch. The shells come, burst and are gone, but that invisible noise keeps on – now near, now far, now near, now far again. Flat, unceasing noise.’

I’ve emphasised the passage that simply resonates with what I described previously as a haptic geography. And so, not surprisingly, the same sources also show that, just as the landscape was inhabited, so too was knowledge of it; that knowing those deadly sounds – ‘knowing the score’, I suppose – was a vital part of staying alive. Here is an extended passage from A.M. Burrage‘s War is war:

We are becoming acclimatised to trench warfare. We know by the singing of a shell when it is going to drop near us, when it is politic to duck and when one may treat the sound with contempt. We are becoming soldiers. We know the calibres of the shells which are sent over in search of us. The brute that explodes with a crash like that of much crockery being broken, and afterwards makes a “cheering” noise like the distant echoes of a football match, is a five-point-nine. The very sudden brute that you don’t hear until it has passed you, and rushes with the hiss of escaping steam, is a whizz-bang. For a perfect imitation of a whizz-bang, sit by the open window of a railway compartment and wait until an express train passes you at sixty miles an hour. The funny little chap who goes tonk-phew-bong is a little high-velocity shell which doesn’t do much harm. “Minnies” and “flying pigs” which are visible by day and night come sailing over like fat aunts turning slow somersaults in mid-air. Wherever one may be, and wherever they may be going to drop, they always look as if they are going to fall straight on top of one. They are visible at night because they have luminous tails, like comets. The thing which, without warning, suddenly utters a hissing sneeze behind us is one of our own trench-mortars. The dull bump which follows, and comes from the middle distance out in front, tells us that the ammunition is “dud.” The German shell which arrives with the sound of a woman with a hare-lip trying to whistle, and makes very little sound when it bursts, almost certainly contains gas.

We know when to ignore machine-gun and rifle bullets and when to take an interest in them. A steady phew-phew-phew means that they are not dangerously near. When on the other hand we get a sensation of whips being slashed in our ears we know that it is time to seek the embrace of Mother Earth.

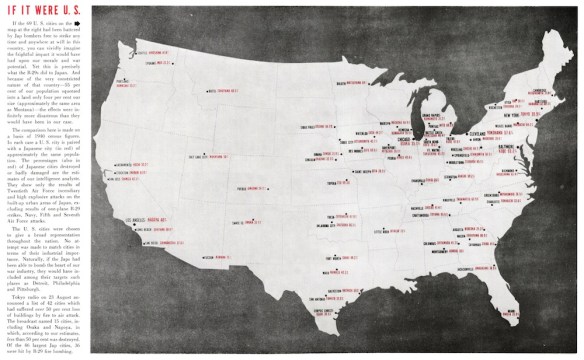

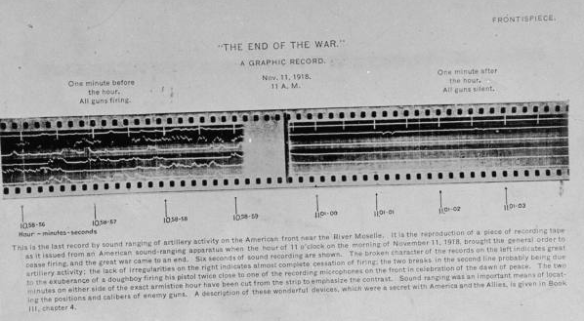

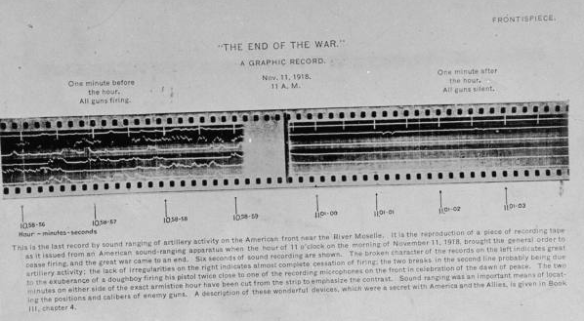

The end of the war was apprehended in both registers, and this frontispiece from Benedict Crowell’s Demobilization (1920) shows how an American sound-ranging station captured the moment the guns fell silent:

‘Stop, hey, what’s that sound?’