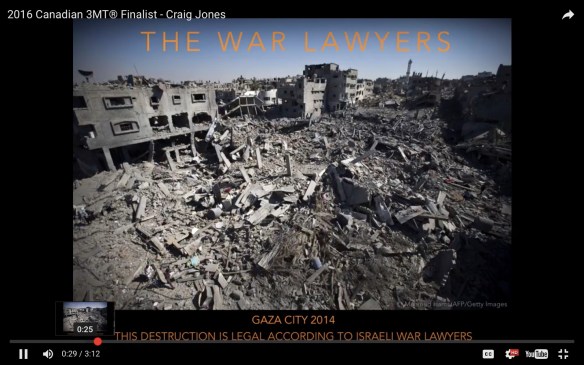

I’ve been working away on my Tanner Lectures, which has plunged me back in to my research on air strikes. There is a dismal topicality to the subject, since in the UK the hawks on both right and left are circling the lobbies in the wake of the attacks in Paris (but still not, it seems, those in Beirut) demanding that yet more bombs fall on Syria. They are less than hawk-eyed, however, since they offer no insight into what – precisely (not exactly the right word where bombing is concerned) – this is designed to achieve. They have learned nothing from the 100-odd years of the history of bombing, or even from its more recent effects.

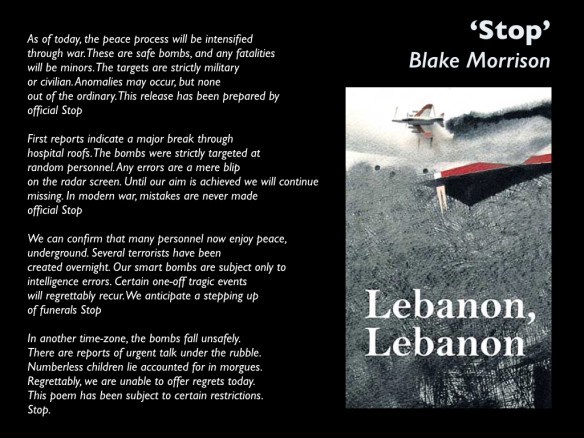

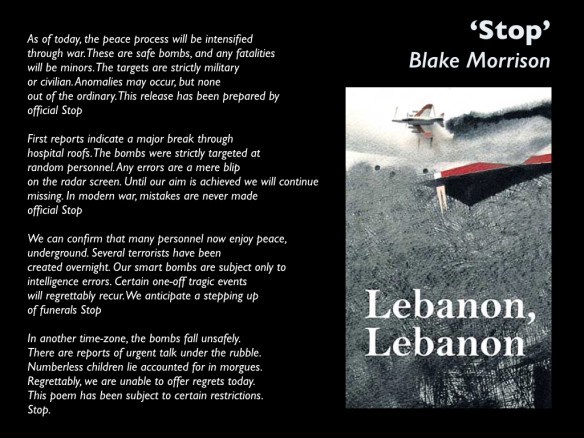

And talking of Beirut: when I delivered a presentation there in 2006, six months after Israel’s devastating air strikes on its southern suburbs, I borrowed my title [‘In another time-zone the bombs fall unsafely’: see DOWNLOADS tab] from Blake Morrison‘s poem ‘Stop’ which was reprinted in an anthology to aid children’s charities in Lebanon:

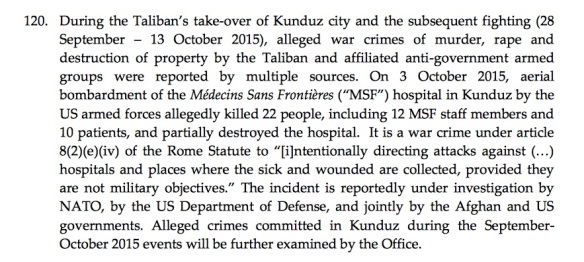

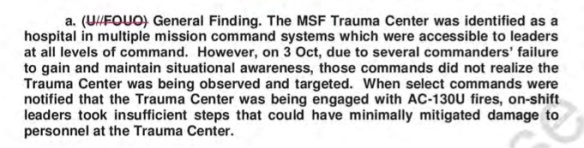

So let me turn to three recent investigations of civilian casualties caused by US air strikes. In each case it’s difficult to say as much as one ought to be able to say: in the first two cases (in Iraq and Syria) the reports have been heavily redacted, and in the third case (the attack on MSF’s hospital in Kunduz) all we have so far is an extended summary (though Kate Clark, as always, does a brilliant forensic job in filleting it here).

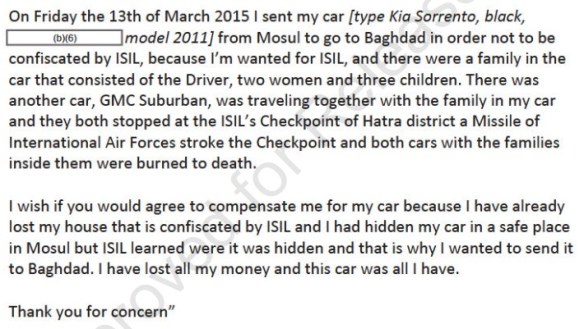

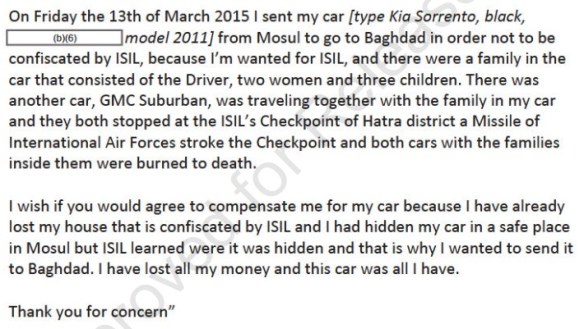

In this post I’ll discuss the report of an investigation into an air strike by two A-10 (‘Warthog’) aircraft on an Islamic State checkpoint near Al Hatra in Iraq on 13 March 2015. On 2 April CENTCOM’s Combined Air Operations Center (CAOC) at Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar was forwarded the following e-mail:

Officers at the CAOC completed an initial ‘Civilian Casualty [CIVCAS] Credibility Assessment’ and agreed that the details in the e-mail were consistent with the known air strike. On 20 April an investigation was established ‘to determine the veracity of the CIVCAS claim’ and, in the event that it was upheld, to review the targeting process ‘to determine if any errors occurred.’ Between 22 April and 1 June the investigating officer interviewed the military personnel involved in the air strike and reviewed intelligence reports and imagery of the target area. This included an examination of the weapons system video (WSV) conducted by an ISR imagery analyst, and a transcript of the associated audio: neither has been released to the public, but you can get a sense of what A-10 imagery can (and cannot) show in this compilation video from Iraq here.

Al Hatra is the site of the ancient fortified city of al Hadr, 2km northwest of the modern settlement (see map above), established under the Seleucids, and after its capture by the Parthians it became one of the major cities of the post-Alexandrian world. Since October, intelligence reports had identified the ruins as an Islamic State training camp, and in March IS announced its intention to level the site and purge it of the ‘symbols of idolatry‘. (In April it released a video showing just that: see the images below, and more here).

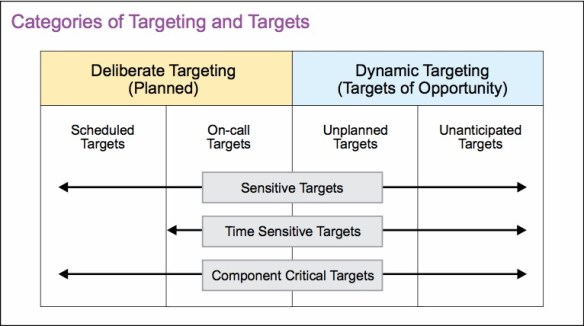

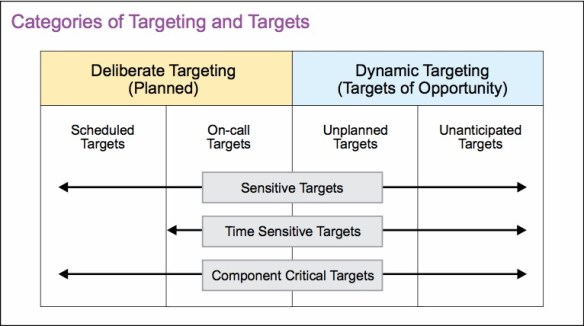

The initial target for the air strike on 13 March was an IS checkpoint and ‘enemy personnel’ who were stopping traffic. They had been seen by an A-10 aircraft en route for refuelling – A10s fly sorties lasting between five and nine hours, and can require two or three inflight refuellings – and the information had been passed to the Dynamic Targeting Cell responsible for drawing up a detailed target folder or target package (a ‘Joint Targeting Message’) for all emergent targets: in effect, targets of opportunity.

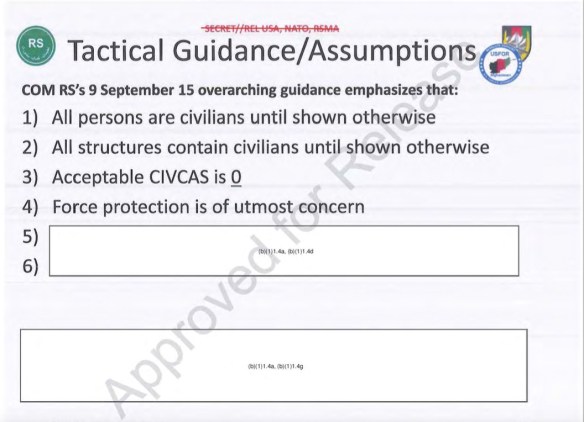

It must have seemed routine to those on duty in the CAOC (shown below): there had been multiple strikes in the vicinity for several months. The Dynamic Targeting Cell cleared the operation via the Battle Director at Al Udeid with the CAOC director who acted as the ‘Target Engagement Authority’ to sanction the strike, with ultimate responsibility for all lethal strikes against Islamic State in Syria and designated areas of western Iraq.

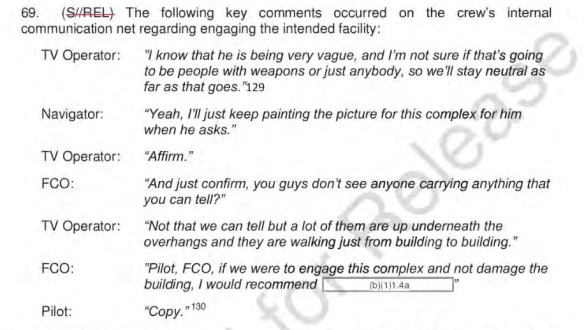

While this was happening, the same aircraft reported that two vehicles had pulled into the side of the road next to the checkpoint (and within ‘the target area outline’: notice how rapidly individuals disappear from view, contained first within objects and then the objects within an area).

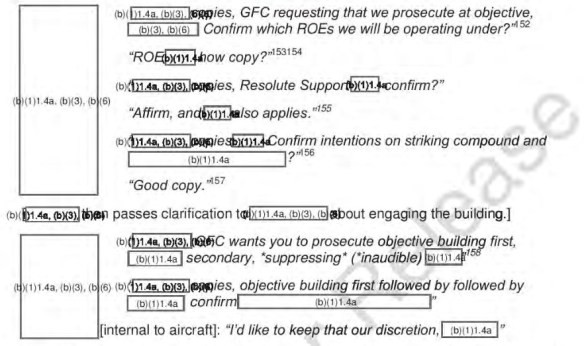

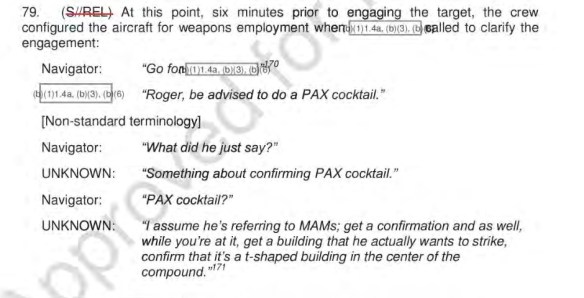

The occupants began to interact with the people manning the checkpoint – the pilot said the two vehicles ‘appeared to be a part of the checkpoint’ but he also made it clear that this was only an ‘opinion’ and that responsibility for the positive identification of the vehicles and passengers as a legitimate target had to rest with superior officers – and the Dynamic Targeting Cell agreed to ‘seek additional authority’. After a short time he radioed back with permission for them to be included as part of the original Joint Targeting Message: ‘You’re cleared to execute Joint Targeting Message [Reference Number] including vehicles and all associated PAX [people/passengers] with PID [Positive Identification].’ The investigating officer evidently thought this perfectly reasonable, agreeing that ‘these vehicles did not display characteristics typical of transient vehicles at checkpoints’; rather than passing through (as seven other vehicles did), they stopped and ‘appeared to be functionally and geospatially tied to the … checkpoint and personnel authorized for strike.’

But this amendment to the original targeting package was never reported up the chain of command to the Target Engagement Authority who only validated the original Joint Targeting Message. He was provided with imagery showing the intended target area, confirmed that it had ‘a single use purpose’, and so had no doubt that the checkpoint and its operators constituted ‘a functionally and geospatially defined object of attack’ and that it was a ‘legitimate military target’ in accordance with international humanitarian law – what the US military prefers to call ‘the law of armed conflict’ – and consistent with the military’s own rules of engagement. The repetition of those qualifiers is vital: the US military defines Positive Identification [PID] as ‘the reasonable certainty that a functionally and geospatially defined object of attack is a legitimate military target’.

The Target Engagement Authority sought no advice from a Judge Advocate, the military lawyer on duty, about the propriety of striking the vehicles and passengers because they were not included in the original package. He testified that ‘at no point was there any discussion of vehicles in association with this strike’: in fact, he explicitly instructed the aircrew ‘to clear for transients [passing vehicles] prior to weapons release.’

The deputy legal adviser to the Combat Operations Division in the CAOC explained that a Judge Advocate was involved in all Dynamic Targeting strikes. The Dynamic Targeting Chief works with the Targets Duty Officer to establish positive identification of the target. The Targets Duty Officer usually spends half of a 12-hour shift on the combat operations floor with the Chief and half with ISR analysts preparing target packages, and it is the responsibility of the Chief to write the ‘5Ws’ – who, what, where, when and why – necessary for any dynamic targeting strike. As the two of them ‘work’ the target, the deputy legal adviser added, they ‘may bring [in] the legal adviser at various times’ throughout the process to provide advice derived from international humanitarian law, the rules of engagement and any special instructions (‘spins’). The Judge Advocate also acts as ‘a second pair of eyes’ scrutinising the co-ordinates of the target and provides legal recommendations to the Target Engagement Authority.

It seems clear, even with the redactions, that in this case the Judge Advocate was not consulted about the (verbal) amendment to the initial targeting package because the procedure was amended as a direct consequence of the incident under investigation. Instead of ‘returning to his or her desk’ once approval had been obtained from the Target Engagement Authority, the Judge Advocate is now required to observe ‘the passing of the Joint Targeting Message and [to] monitor the strike by remaining close to the Dynamic Targeting cell.’

There is also a wider responsibility: the deputy legal adviser made it clear that ‘anyone in the chain or the Dynamic Targeting cell has the responsibility to call an abort on the strike if the conditions change.’ In this case, clearly, they did – but nobody intervened.

The Dynamic Targeting Chief claims he telephoned the Battle Director for permission to extend the original Joint Targeting Message, but the exchange took just 80 seconds. One witness – who may well have been the Battle Director: it’s impossible to know for sure – thought this highly unlikely: 80 seconds would have been ‘very, very quick for [him] to take a call, gather the information, relay it to the Targeting Engagement Authority, get approval, and then relay it back down to [the Dynamic Targeting Cell].’ And the CAOC director was adamant: ‘even if the aviators could identify the vehicles as hostile … there was still no authority to strike without requesting authorization for a Joint Targeting Message change‘ from him.

The A-10’s sensor remained ‘padlocked on these vehicles’ and when the pilot was finally cleared to engage he naturally assumed that the Target Engagement Authority had been satisfied by their inclusion in the target package. Six seconds before they were hit, four people got out; the ISR analyst reviewing the post-strike video concluded that one of them was possibly a child. But the investigating officer emphasised that they were only visible on the weapons system video and only after being played back at slow speed: ‘There is no reasonable expectation that [the pilot] could have seen, assessed and called for ABORT on the strike through real-time viewing of his targeting pod display inflight.’ The A-10 has a targeting pod under one wing which, as Andrew Cockburn reports, ‘ in daylight transmits video images of the ground below, and infrared images at night. This video feed is displayed on the plane’s instrument panel.’ As the pilot approached the target and entered his ‘weapons engagement envelope’ – again, note the geometric disposition – the investigating officer accepts that neither could he have ‘been able to discriminate between combatant and non-combatant personnel’.

The vehicles were attacked with the A-10’s 30mm rotary cannon – ‘a good weapon for reducing collateral damage’, according to one pilot (see the image below!) – and soon after a second A-10 dropped a single GBU-38 bomb and destroyed the guard shack; this is a conventional 500 lb bomb converted into a ‘guided bomb’, a ‘precision munition’, through the incorporation of a GPS/inertial navigation system so that it can attain a circular error probable of between 10 and 30 metres (which means that, assuming a bivariate normal distribution and all other things being equal, then 50% of the time it will land within that radius: which also means that the other half of the time it won’t, even under ideal experimental conditions).

Here is how that same pilot (who was not, so far as I know, flying this mission) characterised these operations against IS to Tom Philpott in April:

A-10 pilots are trained to find a target, seek verification and do on-the-fly targeting and strike. While that sounds like a solo operation, Stohler says “the coalition flying up there is enormous and we work as a team.”

Almost all targets get vetted up to higher command to determine validity. “As you can imagine this is complex,” Stohler says… The most challenging moment “is the weapon employment phase of the flight,” says Stohler. “Our number one focus is to deliver the ordnance on target, on the first pass, while minimizing collateral damage. This takes a great deal of skill that our pilots train to daily back home.”

“I tell our guys this is like trying to drop bombs on bad guys in your hometown. Your goal is not to hurt anyone else, or destroy anything that you don’t have to destroy. It’s a constant challenge to do that and we do it very well.”

But while collateral damage is key it might not be “a showstopper,” says Stohler. “Clearly if the target we need to hit is significant we will employ on it wherever it is – if we have the approval.”

In this case it took under an hour from first observing the checkpoint to striking the target; only eight minutes elapsed between the confirmation of the Joint Targeting Message and the execution of the strike; and it took just three or four seconds ‘from trigger squeeze to impact’. According to the e-mail, at least two women and three children were killed. The military decided not to award the writer of that message any compensation for the destruction of her vehicle and no solatia payments will be made to the families of the deceased since no survivors have come forward to ask for them.

CENTCOM’s press release summarising the investigation is a model of complacency and fails to include any of the qualifications and mis-steps I’ve noted in the previous paragraphs:

Based on the actions being observed, aircrew and CAOC personnel assessed that the checkpoint, additional vehicles, and additional personnel were lawful targets consistent with the Law of Armed Conflict (LOAC) at the time the weapon was released on the target area.

The investigation concluded that the airstrikes resulted in the destruction of the intended target, and that the two vehicles parked at the checkpoint were also hit. Upon further review, it was determined that all ordnance functioned properly and accurately struck the intended target.

The investigation concluded that the airstrikes were conducted in accordance with applicable military authorizations, targeting guidance, and LOAC. The target engaged was a valid military target, and the LOAC principles of military necessity, proportionality, and distinction were observed. All reasonable measures were taken to avoid unintended deaths of or injuries to non-combatants by reviewing the targets thoroughly prior to engagement, relying on accurate assessments of the targets, and engaging the targets when the risk to non-combatants was thought to be minimized.

Micah Zenko has an analysis of this strike here, and he adds these chilling paragraphs:

To intensify the U.S.-led coalition’s war against the Islamic State … the Pentagon is considering further loosening the rules of engagement (ROEs) that are intended to minimize civilian casualties and expanding the target sets that can be bombed…

The first problem with this theory is that large militant armies are not defeated, either exclusively or primarily, with air power. Military and civilian policymakers repeat the mantra that “you can’t kill your way out” of the problem posed by such adversaries, but then continue to call upon air power to do just that. This is despite the fact that all of the militant armies and terrorist groups that have been bombed and droned for the past 14 years have survived. None have been completely destroyed, which is allegedly the strategic objective against the Islamic State. Moreover, the size of the al Qaeda-affiliated groups that the United States claims to be at war with have either stayed flat or grown, while the total number of State Department-designated Foreign Terrorist Organizations has grown from 34 in 2002 to 59 in 2015.

However, the larger concern with this mindset is the assured growth of collateral damage and civilian casualties that will accompany significantly loosened ROEs. Last month, Lt. Gen. Bob Otto, the U.S. Air Force’s deputy chief of staff for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance, observed that the coalition was “challenged in finding enough targets that the airplanes can hit that meet the rules of engagement.” However, he added an important caveat: “If you inadvertently — legally — kill innocent men, women, and children, then there’s a backlash from that. And so we might kill three and create 10 terrorists.”

And yet, as Micah emphasizes, there have been only two military investigations into civilian casualties throughout the air campaign against IS:

8,300 airstrikes, 16,000 Islamic State targets destroyed, more than 20,000 Islamic State fighters killed — and only two claims of collateral damage. Either the U.S.-led coalition is really, really, really good at bombing these days, or they are shooting first and not asking questions later.

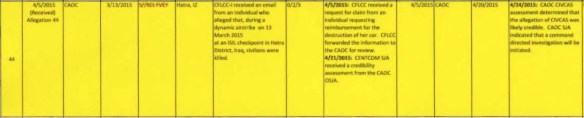

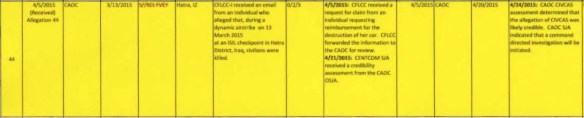

More in the same vein from Joseph Trevithick at War is Boring here. You can access the US Air Force’s own (secret) tabulation of CIVCAS allegations here, which lists 45 separate incidents, far in excess of the two that have been officially acknowledged to date. Joseph notes that most of them were dismissed within 48 hours as ‘not credible’ because there was ‘insufficient evidence’ or ‘insufficient information.’ Al Hatra was number 44:

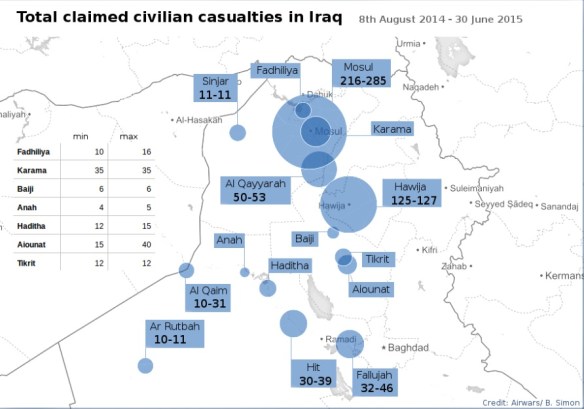

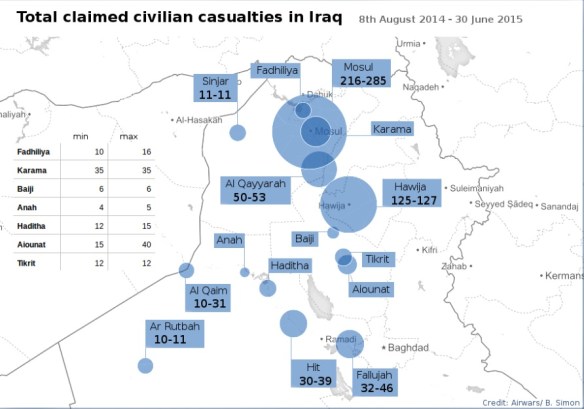

The Airwars team has provisionally estimated that from 8 August 2014 to 24 November 2015 ‘between 682 and 977 civilian non-combatants are likely to have been killed in 113 incidents where there is fair reporting publicly available of an event, and where Coalition strikes were confirmed in the near vicinity on that date.’ I’ve pasted their map of total claimed civilian casualties in Iraq (to 30 June 2015) below; you can find their full report, Cause for Concern, here.

To be continued. Sadly.