Yet more on violations of medical neutrality in contemporary conflicts (see my posts here, here, here and here). Over at Afghan Analysts Network Kate Clark provides a grim review of (un)developments in Afghanistan, Clinics under fire? Health workers caught up in the Afghan conflict.

Those providing health care in contested areas in Afghanistan say they are feeling under increasing pressure from all sides in the war. There have been two egregious attacks on medical facilities in the last six months: the summary execution of two patients and a carer taken from a clinic in Wardak by Afghan special forces in mid-February – a clear war crime – and the United States bombing of the Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) hospital in Kunduz in October 2015, which left dozens dead and injured – an alleged war crime. Health professionals have told AAN of other violations, by both pro and anti-government forces. Perhaps most worryingly, reports AAN Country Director Kate Clark, have been comments by government officials, backing or defending the attacks on the MSF hospital and Wardak clinic [see image below].

So, for example:

Afghan government reactions to the news of the Wardak killings [at Tangi Sedan during the night of 17/18 February 2016; see also here] came largely at the provincial level, from officials who saw no problem in those they believed were Taleban – wounded or otherwise – being taken from a clinic and summarily executed. Head of the provincial council, Akhtar Muhammad Tahiri, was widely quoted, saying: “The Afghan security forces raided the hospital as the members of the Taliban group were being treated there.” Spokesperson for the provincial governor, Toryalay Hemat, said, “They were not patients, but Taliban,” and “The main target of the special forces was the Taliban fighters, not the hospital.” Spokesman for Wardak’s police chief, Abdul Wali Noorzai, said “Those killed in the hospital were all terrorists,” adding he was “happy that they were killed.”

Yet, the killings were a clear war crime. The Laws of Armed Conflict, also known as International Humanitarian Law, give special protection to medical facilities, staff and patients during war time – indeed, this is the oldest part of the Geneva Conventions. The Afghan special forces’ actions in Wardak involved numerous breaches: forcibly entering a medical clinic, harming and detaining staff and killing patients. The two boys and the man who were summarily executed were, in any case, protected either as civilians (the caretaker clearly, the two patients possibly – they had claimed to have been injured in a motorbike accident) or as fighters who were hors d’combat (literally ‘out of the fight’) because they were wounded and also then detained. Anyone who is hors d’combat is a protected person under International Humanitarian Law and cannot be harmed, the rationale being that they can no longer defend themselves. It is worth noting that, for the staff at the clinic to have refused to treat wounded Taleban would also have been a breach of medical neutrality: International Humanitarian Law demands that medical staff treat everyone according to medical need only.

That the Wardak provincial officials endorsed a war crime is worrying enough, but their words echoed reactions from more senior government officials to the US military’s airstrikes on a hospital belonging to the NGO Médecins Sans Frontières on 3 October 2015. Then, ministers and other officials appeared to defend the attack by saying it had targeted Taleban whom they said were in the hospital (conveniently forgetting that, until the fall of Kunduz city became imminent when the government evacuated all of its wounded from the hospital except the critically ill, the hospital had largely treated government soldiers). The Ministry of Interior spokesman, for example, said, “10 to 15 terrorists were hiding in the hospital last night and it came under attack. Well, they are all killed. All of the terrorists were killed. But we also lost doctors. We will do everything we can to ensure doctors are safe and they can do their jobs.”

MSF denied there were any armed men in the hospital. However, even if there had been, International Humanitarian Law would still have protected patients and medical staff: they would still have had to have been evacuated and warnings given before the hospital could have been legally attacked.

Not surprisingly heads of various humanitarian agencies all reported that the situation was worsening:

“General abuses against medical staff and facilities are on the rise from all parties to the conflict,” said one head of agency, while another said, “We have a good reputation with all sides, but we have still had threats from police, army and insurgents.” The head of a medical NGO described the situation as “messy, really difficult”:

All health facilities are under pressure. We have had some unpleasant experiences, The ALP [Afghan Local Police] are not professional, not disciplined. If the ALP or Taleban take over a clinic, we rely on local elders [to try to sort out the situation]. We are between the two parties.

He described the behaviour of overstretched Afghan special forces as “quite desperate,” adding, “They are struggling, trying to be everywhere and get very excited when there’s fighting.” Most of them, he said, were northerners speaking little or no Pashto, which can make things “difficult for our clinics in the south.”

The head of another agency listed the problems his staff are facing:

“We have seen the presence of armed men in medical facilities, turning them into targets. We have seen violations by the ANSF [Afghan National Security Forces], damage done to health facilities that were taken over as bases to conceal themselves and fight [the insurgents] from. We have seen checkpoints located close to health centres. Why? So that in case of hostilities, forces can take shelter in the concrete building. We have seen looting. We have seen ANSF at checkpoints deliberately causing delays, especially in the south, including blocking patients desperately needing to get to a health facility. We can never be certain that [such a delay] was the cause of death, but we believe it has been.”

He said his medical staff had been threatened by “ANSF intervening in medical facilities at the triage stage, forcing doctors to stop the care of other patients and treat their own soldiers, in disregard of medical priorities.” Less commonly, but more dangerously for the doctors themselves, he said, was the threat of Taleban abduction. He described a gathering of surgeons in which all reported having been abducted from their homes at least once and brought to the field to attend wounded fighters “with all the dangers you can imagine along the road.” He said the surgeons were “forced to operate without proper equipment and forced to abandon their own patients in clinics because the abduction would last days.”

Locally, medical staff often try to mitigate threats from both government forces and insurgents by seeking protection first from the local community. One head of agency described their strategy:

“When we open a clinic, our first interlocutors are the elders. Everyone wants a clinic in their area, but we decide the location and make the elders responsible for the clinic… They have to give us a building – three to four rooms. All those who work in the clinic – the ambulance driver, the owner of the vehicle, everyone – come from the area. We also need the elders to deal with the parties… If the ALP or Taleban take over clinic, we always start with the elders [who negotiate with whoever has taken over the clinic].”

However, this tactic puts a burden on community elders who may not be able to negotiate if the ANSF, ALP or insurgents are also threatening them.

***

I’ve delayed following up my previous commentaries on the US airstrike on the MSF Trauma Center in Kunduz (here and here) because I had hoped the full report of the internal investigation carried out by the US military would be released: apparently it runs to 3,000-odd pages. I don’t for a minute believe that it would settle matters, but in any event nothing has emerged so far – though I’m sure it’s subject to multiple FOIA requests and, if and when it is released, will surely have been redacted.

All we have is an official statement by General John Campbell on 25 November 2015 (above), which described the airstrike as ‘a tragic, but avoidable accident caused primarily by human error’, and a brief Executive Summary of the findings of the Combined Civilian Casualty Assessment Team (made up of representatives from NATO and the Afghan government) which emphasised that those errors were ‘compounded by failures of process and procedure, and malfunctions of technical equipment.’

The parallel investigations identified a series of cumulative, cascading errors and malfunctions:

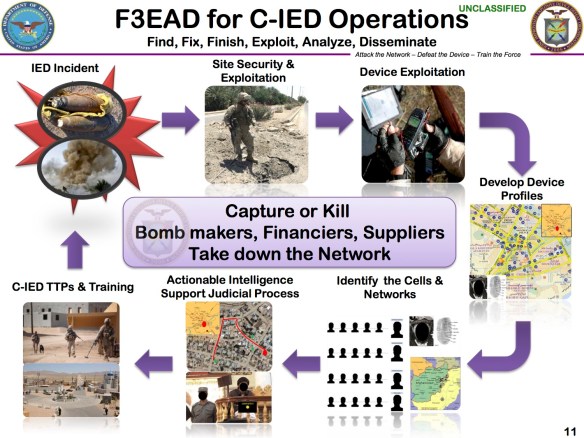

(1) The crew of the AC-130 gunship that carried out the attack set out without a proper mission brief or a list of ‘no-strike’ targets; the aircraft had been diverted from its original mission, to provide close air support to ‘troops in contact’, and was unprepared for this one (which was also represented as ‘troops in contact’, a standard designation meaning that troops are under hostile fire).

(2) Communications systems on the aircraft failed, including – crucially – the provision of video feeds to ground force commanders and the transmission of electronic messages (the AC-130 has a sophisticated sensor and communications suite – or ‘battle management center’ –on board, staffed by two sensor operators, a navigator, a fire control officer, and an electronic warfare officer, and many messages are sent via classified chat rooms).

The problem was apparently a jerry-rigged antenna that was supposed to link the AC-130 to the ground. Here is how General Bradley Heithold explained it to Defense One:

“Today, we pump full-motion video into the airplane and out of the airplane. So we have a Ku-band antenna on the airplane … the U-model…. On our current legacy airplanes, the solution we used was rather scabbed on: take the overhead escape hatch out, put an antenna on, stick it back up there, move the beams around. We’ve had some issues, but we’re working with our industry partners to resolve that issue.”

He added, “99.9 percent of the time we’ve had success with it. These things aren’t perfect; they’re machines.”

Heithold said that dedicated Ku-band data transfer is now standard on later models of the AC-130, which should make data transfer much more reliable.

(3) Afghan Special Forces in Kunduz had requested close air support for a clearing operation in the vicinity of the former National Directorate of Security compound, which they believed was now a Taliban ‘command and control node’. The commander of US Special Forces on the ground agreed and provided the AC-130 crew with the co-ordinates for the NDS building. He could see neither the target nor the MSF Trauma Center from his location but this is not a requirement for authorising a strike; he was also working from a map that apparently did not mark the MSF compound as a medical facility. According to AP, he had been given the coordinates of the hospital two days before but said he didn’t recall seeing them. The targeting system onboard the AC-130 was degraded and directed the aircraft to an empty field and so the crew relied on a visual identification of the target using a description provided by Afghan Special Forces – and they continued to rely on their visual fix even when the targeting system had been re-aligned (‘the crew remained fixated on the physical description of the facility’) and, as David Cloud points out, even though there was no visible sign of ‘troops in contact’ in the vicinity of the Trauma Center (‘An AC-130 is normally equipped with infrared surveillance cameras capable of detecting gunfire on the ground’):

Sundarsan Raghaven adds that ‘Not long before the attack on the hospital, a U.S. airstrike pummeled an empty warehouse across the street from the Afghan intelligence headquarters. How U.S. personnel could have confused its location only a few hours later is not clear…’ More disturbingly, two US Special Forces troops have claimed that their Afghan counterparts told their commander that it was the Trauma Center that was being used as the ‘command and control node’, and that the Taliban ‘had already removed and ransomed the foreign doctors, and they had fired on partnered personnel from there.’

(4) The aircrew cleared the strike with senior commanders at the Joint Operations Center at Bagram and provided them with the co-ordinates of the intended target. Those commanders failed to recognise that these were the co-ordinates of the MSF hospital which was indeed on the ‘no-strike’ list; ‘this confusion was exacerbated by the lack of video and electronic communications between the headquarters and the aircraft, caused by the earlier malfunction, and a belief at the headquarters that the force on the ground required air support as a matter of immediate force protection’;

(5) The strike continued even after MSF notified all the appropriate authorities that their clinic was under attack; no explanation was offered, though the US military claims the duration was shorter (29 minutes) than the 60-minutes reported by those on the ground.

Campbell announced that those ‘most closely associated’ with the incident had been suspended from duty for violations of the Rules of Engagement – those ‘who requested the strike and those who executed it from the air did not undertake the appropriate measures to verify that the facility was a legitimate military target’ – though he gave no indication how far up the chain of command responsibility would be extended; in January it was reported that US Central Command was weighing disciplinary action against unspecified individuals. In the meantime, solatia payments had been made to the families of the killed ($6,000) and injured ($3,000).

Not surprisingly, MSF reacted angrily to Campbell’s summary: according to Christopher Stokes,

‘The U.S. version of events presented today leaves MSF with more questions than answers. The frightening catalog of errors outlined today illustrates gross negligence on the part of U.S. forces and violations of the rules of war.’

Joanne Liu, MSF’s President, subsequently offered a wider reflection on war in today’s ‘barbarian times’, prompted by further attacks on other hospitals and clinics in Afghanistan, Syria, Yemen and elsewhere:

“The unspoken thing, the elephant in the room, is the war against terrorism, it’s tainting everything,” she said. “People have real difficulty, saying: ‘Oh, you were treating Taliban in your hospital in Kunduz?’ I said we have been treating everyone who is injured, and it will have been Afghan special forces, it will have been the Taliban, yes we are treating everybody.”

She added: “People have difficulty coming around to it. It’s the core, stripped-down-medical-ethics duty as a physician. If I’m at the frontline and refuse to treat a patient, it’s considered a crime. As a physician this is my oath, I’m going to treat everyone regardless.”

Kate Clark‘s forensic response to the US investigation of the Kunduz attack is here; she insists, I think convincingly, that

‘… rather than a simple string of human errors, this seems to have been a string of reckless decisions, within a larger system that failed to provide the legally proscribed safeguards when using such firepower. There were also equipment failures that compounded the problem but, again, if the forces on the ground and in the air had followed their own rules of engagement, the attack would have been averted.’

This is what just-in-time war looks like, but it’s not enough to blame all this on what General Campbell called a ‘high operational tempo’. As a minimum, we need to be able to read the transcripts of the ground/air communications – which are recorded as a matter of course, no matter what the tempo, and which are almost always crucial in any civilian casualty incident resulting from ‘troops in contact’ (see, for another vivid example, my discussion here) – to make sense of the insensible.