For the longest time the only victims of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder from the wars in Afghanistan who were accorded any media attention in Europe and North America were ground troops, drone pilots and on occasion foreign civilians who worked in the combat zone. And much of that discussion focussed on the ways in which, as Sebastian Junger put it, the effects of PTSD ripple far beyond the battlefield:

For the longest time the only victims of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder from the wars in Afghanistan who were accorded any media attention in Europe and North America were ground troops, drone pilots and on occasion foreign civilians who worked in the combat zone. And much of that discussion focussed on the ways in which, as Sebastian Junger put it, the effects of PTSD ripple far beyond the battlefield:

[Veterans] return from wars that are safer than those their fathers and grandfathers fought, and yet far greater numbers of them wind up alienated and depressed. This is true even for people who didn’t experience combat. In other words, the problem doesn’t seem to be trauma on the battlefield so much as re-entry into society.

But what about those denied re-entry into ‘normal’ society, those for whom war long ago became the ‘new normal’? Apart from the odd glance at other combatants – ‘Do the Taliban get PTSD?‘ Newsweek once asked – the plight of local people trapped in the battlefield, living and dying every day in the shadows of military and paramilitary violence, has been largely ignored.

There have been exceptions, like Anna Badkhen‘s report for the Pulitzer Center on Afghanistan as ‘PDSTland’ that also offered a more general commentary:

Compared with research into the effects of conflict on U.S. war veterans, studies of combat trauma among civilians are few. But there is a growing understanding among medical scientists and conflict experts that the emotional toll of war on noncombatants is more significant than had been assumed. During World War I, when military physicians described soldiers’ traumatic reactions to war as “shell shock,” about nine out of 10 war casualties were fighters. But after nearly 50 years of the Cold War and more than 10 years of the war on terror, the way we wage war is more personal. Terrorism battlefields recognize no front lines. Vicious sectarian rampages pit neighbor against neighbor. Victims of genocidal campaigns often know their attackers by name. In the most current conflicts, at least nine out of 10 war casualties are believed to be civilians, writes psychologist Stanley Krippner in his book The Psychological Impact of War Trauma on Civilians [This is a collection of essays Krippner co-edited with Maria McIntyre]. In Iraq, where as many as 1 million people may have died since 2003, the rate might be even higher. No one kept track of civilian casualties in Afghanistan between 2001 and 2007, and estimates vary widely; given the United Nations’ tally of almost 12,000 civilian deaths since the beginning of 2007, a rough guess of between 20,000 and 30,000 civilian casualties since 2001 seems reasonable.

Communal psychological wounds – what medical anthropologist Arthur Kleinman has called “social suffering” – permeate the lives of survivors scraping by in unimaginable poverty amid collapsed infrastructure, the common afterbirth of modern combat. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, between 30 and 70 percent of people who have lived in war zones bear the scars of post-traumatic stress disorder and depression.

Over the years I’ve read endless reports about the ways in which the US military in particular is exploring new therapies for PTSD – including experiments in Virtual Reality as a way of helping victims re-live and ultimately come to terms with trauma, like Virtually Better‘s Bravemind staged in ‘Virtual Afghanistan’ (see below; also here, here, here and here).

This doesn’t mean that progress is rapid or solutions straightforward, and David Morris‘s The Evil Hours ought to banish any such complacency. Here is Tom Ricks:

From battlefields and cultural responses to traumatized warriors throughout world history to the internecine corridors of the San Diego V.A. hospital and the modern psychology establishment, Morris gives sight to the blind examining the PTSD elephant, offering up a clear understanding of what the beast is as well as the path it’s traveled across the landscape of warfare. He draws from a seemingly inexhaustible well of experience. Herding a cast that includes Hemingway, Klosterman, Sassoon, a host of anthropologists and neurologists, and the soldiers and veterans he met throughout his own odyssey, Morris accomplishes the necessary work of identifying all the necessary aspects of PTSD and still finds a way to magnify the nuances of how it affects individuals and societies.

The “out-of-body” experience and the recurring memory of traumatic events are familiar to those afflicted by PTSD. Many describe it as watching a movie on repeat from every possible angle. It’s the mind’s vain attempt to challenge trauma like a call in a football game, gathering the referees around a screen to watch the replay over and over until the past can be rewritten in favor of justice. Others who have attempted books about PTSD have floundered in this conceit. Morris avoids that and maintains his place at the commentators’ desk — close enough to call the play-by-play, but far enough away to keep perspective. Instead of raging at length about the process of enrolling in the V.A. care system (whose bureaucracy he declares forces veterans to run “a patience marathon”), he reflects on its problematic advocacy of “large, scalable, Evidence-Supported Treatments.” Morris unearths troubling aspects in the character of these treatments as he traces the history of PTSD therapy. He finds that they are highly impersonal … and make the afflicted feel more like they’re being treated as lab rats than patients. He observes that these methods are a profound departure from the type of treatments discovered and evolved by W.H.R. Rivers during WWI and, later, Vietnam veterans groups during the 1970s. Though Morris’s own experience with prolonged exposure treatment met with poor results and he expresses misgivings about similar therapeutic methods, he remains objective about their efficacy. Rather, he takes a more important and less scrutinized view of how treatments are vetted in the first place. Questioning the practice of excluding patients who drop out of test programs from data sets instead of listing them as showing no signs of improvement, Morris asks if reports inaccurately portray success rates. This leaves the V.A.’s dogmatic insistence on evidence-based methods particularly vulnerable to skewed numbers… His exploration of the pharmaceutical approach to PTSD reaches similar conclusions. As Morris writes, “‘Evidence-supported’ and ‘evidence-based’ mostly means that a lot of doctors happen to like it, oftentimes for reasons that have less to do with the actual value of a therapeutic protocol than with trendiness.”

So PTSD has become a medical-psychological-psychiatric and even -technological minefield, and the figure of what Roy Scranton calls ‘the trauma hero‘ still casts a long shadow over its deformations (and even contributes to them).

But when you compare these avowedly fraught therapeutic interventions with the often forcible recourse of many Afghan victims of PTSD to shrines, a radically divergent medical geography comes into view (much as it does when you compare the differential treatment for catastrophic injury: see my commentary on ‘The prosthetics of military violence’ here). Anna writes:

Most Afghans turn for comfort to religious shrines – small mausoleums or simply fenced, coffin-sized ziggurats, painted green and laced with shreds of shiny cloth that sparkle along country roads and hillsides like jewels. Pilgrims come to kneel or lie prostrate next to the metal palisades, seeking delivery from the djinns that possess them – evil spirits that trigger sudden violent outbursts and long bouts of melancholia, that bedevil their sleepless nights with nightmares and turn their days into lethargic slogs.

This doubly dreadful world is portrayed in a new film by Jamie Doran and Najibullah Quraishi for Al Jazeera, Living beneath the drones (which you can also access on YouTube if the embedded video fails).

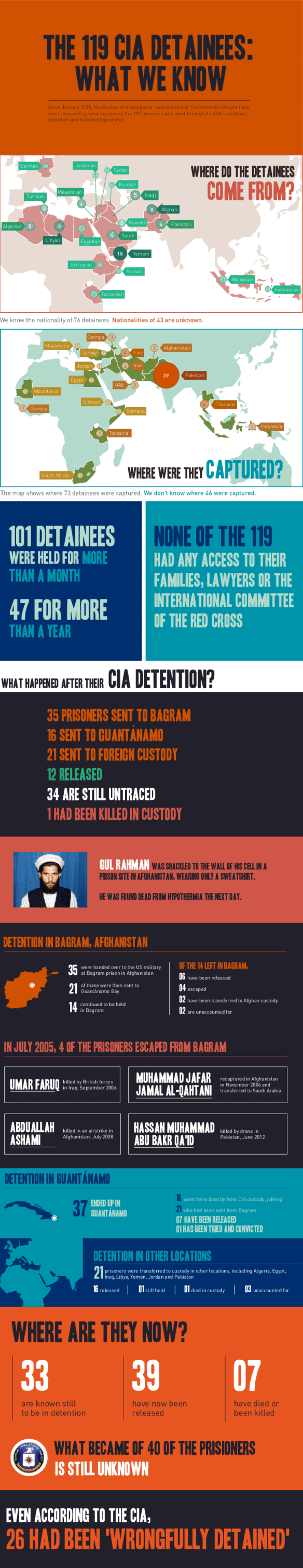

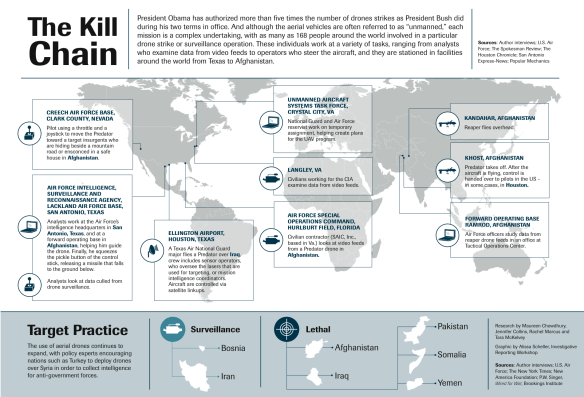

This is not the first time that the trauma of living beneath the ‘persistent presence’ of Predators and Reapers has been brought to critical attention, most vividly in the NYU/Stanford study Living Under Drones: Death, injury and trauma to civilians from US drone practices in Pakistan (2012). But this is the first time I’ve seen such a detailed investigation of the impact of military violence on the people of Afghanistan. As I’ve noted before, it’s taken a remarkably long time for investigators to examine the role of remote warfare in Afghanistan – ‘remote’ in more ways than one – and Living beneath the Drones includes the standard interviews with David Deptula and Peter Singer who offer their usual contrasting views about its effects.

But for me this is the least important contribution of the film; it’s the intimate exposure of the treatment meted out to traumatised victims of military and paramilitary violence that is most unsettling. In fact, it’s not easy to disentangle the impact of Predators and Reapers from the larger matrix of violence in which they are enmeshed. True, many of those interviewed describe how their lives are haunted by the drones, but this is a country where the dogs of war have prowled for four generations or more and trauma has never been rationed. As Kevin Sieff’s report for the Washington Post in October 2012 showed, it’s usually impossible to fasten on a single incident or even to get an adequate history:

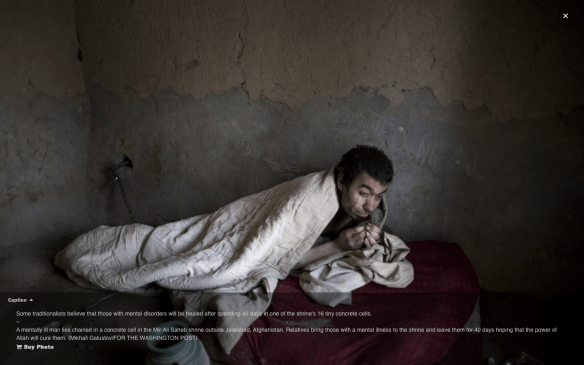

No one here knows the man whose left leg is shackled to the wall of cell No. 5. Last week, he finished tearing his mattress to shreds and then moved onto his clothes, ripping his shirt and pants off before falling asleep naked…

The man’s brothers drove him here from southern Kandahar province two weeks ago, drawn by the same belief that has attracted families from across Afghanistan for more than two centuries. Legend has it that those with mental disorders will be healed after spending 40 days in one of the shrine’s 16 tiny concrete cells. They live on a subsistence diet of bread, water and black pepper near the grave of a famous pir, or spiritual leader, named Mia Ali Sahib.

Every year, hundreds of Afghans bring mentally ill relatives here rather than to hospitals, rejecting a clinical approach to what many here see as a spiritual deficiency. The treatment meted out at the shrine and a handful of others like it nationwide might be archaic, but the symptoms are often a response to 21st-century warfare: 11 years of night-time raids, assassinations and suicide bombings.

For over a decade, Western donors have helped train Afghan psychiatrists, who diagnose many of their patients as having an ailment with a distinctly modern acronym: PTSD, or post-traumatic stress disorder. Mental health departments in Afghanistan are plastered with posters detailing the disorder’s symptoms. Pharmacies are stocked with antipsychotic drugs.

But many of those suffering from the disorder never see doctors or pharmacists. Instead, they are taken on the long, unmarked dirt road, through a village of mud huts, that leads to an L-shaped agglomeration of cells.

The brothers of the man in cell No. 5 drove back to Kandahar, more than 400 miles away, once the shackles were in place. They left an indecipherable phone number on a scrap of paper. They paid $20 for the treatment, as all patients must. If they told anyone the name of the man, no one remembers.

“What will I do with this man?” asked Shafiq, the shrine’s director and a descendant of Sahib. “Who is this man?”

Shafiq wondered: Was the man’s mental state a product of war? Was he a former soldier? A civilian who had seen too much horror?

And so here is Emma Reynolds on what I take to be the central message of Living beneath the drones:

When a Western soldier suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder, there are doctors and organisations who can help them recover from the heartbreaking legacy of war.

When it is someone from Afghanistan, where bombings regularly wreak devastation and tear families apart, you are unlikely to find any assistance, since there is little understanding of mental illness in the country.

“The most common treatment is to take your loved one to a religious shrine where they are chained to walls or trees for up to 40 days, fed stale bread, water and ground pepper, and read dubious lines from the Qur’an by individuals with no medical or, for that matter, religious training,” documentary-makers Jamie Doran and Najibullah Quraishi [said]…

Many of the shrines are nothing more than money-making enterprises run by con artists with little or no religious training…

You might have thought that civilians and soldiers living in war zones would become hardened to this life, and find it almost normal. In fact, the pervasive atmosphere of violence and fear takes a bitter toll, and this terrible truth can be seen most clearly in Afghanistan, the site of the longest war ever for Australia and the US. “When you talk to them, there is little joy in their words any more,” said UK-based director Doran… “Anyone with a family, children, someone you love, is forever in fear of losing them. You can see it in their worn faces.”

Hope and confidence in the future had steadily dissolved, with millions now thought to be suffering from PTSD, with little hope of treatment. Only one hospital in the entire country is dedicated to mental health, despite official estimates indicating that 60 to 70 per cent of the country’s population now suffer from some mental health problem. Unofficial estimates go as high as 95 per cent. This is the real human impact of living with the daily threat of death.