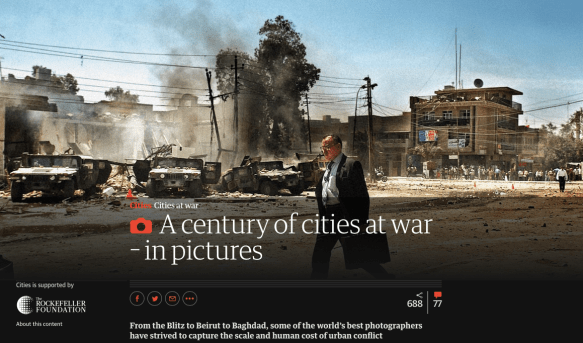

This week the Guardian launched a new series on Cities and War:

War is urbanising. No longer fought on beaches or battlefields, conflict has come to the doors of millions living in densely populated areas, killing thousands of civilians, destroying historic centres and devastating infrastructure for generations to come.

Last year, the world watched the Middle East as Mosul, Raqqa, Sana’a and Aleppo were razed to the ground. Across Europe, brutal attacks stunned urban populations in Paris, London and Berlin, while gang warfare tore apart the fabric of cities in central and south America.

In 2018, Guardian Cities will explore the reality of war in cities today – not merely how it is fought, but how citizens struggle to adapt, and to rebuild stronger than ever.

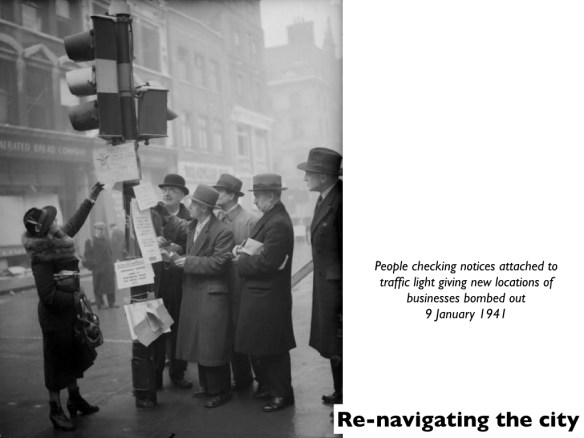

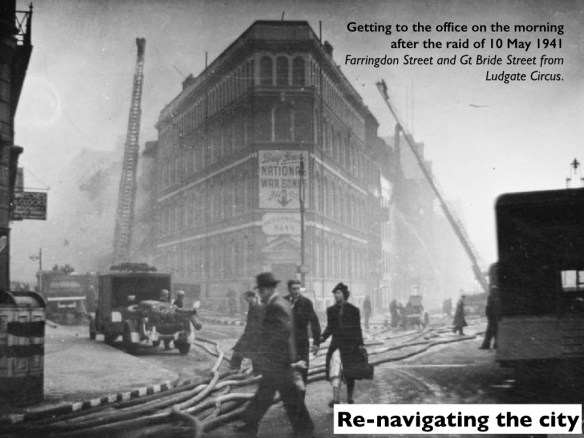

The series opened on Monday with a photographic gallery illustrating ‘a century of cities at war’; some of the images will be familiar, but many will not. When I was working on ‘Modern War and Dead Cities‘ (which you can download under the TEACHING tab), for example, I thought I had seen most of the dramatic images of the Blitz, but I had missed this one:

It’s an arresting portfolio, and inevitably selective: there is a good discussion below the line on what other cities should have made the cut.

The first written contribution is an extended essay from Jason Burke, ‘Cities and terror: an indivisible and brutal relationship‘, which adds a welcome historical depth and geographical range to a discussion that all too readily contracts around recent attacks on cities in Europe and North America, and suggests an intimate link between cities and terrorism:

[I]t was around the time of the Paddington station attack [by Fenians in 1883] that the strategy of using violence to sway public opinion though fear became widespread among actors such as the anarchists, leftists and nationalists looking to bring about dramatic social and political change.

This strategy depended on two developments which mark the modern age: democracy and communications. Without the media, developing apace through the 19th century as literacy rates soared and cheap news publications began to achieve mass circulations, impact would be small. Without democracy, there was no point in trying to frighten a population and thus influence policymakers. Absolutist rulers, like subsequent dictators, could simply ignore the pressure from the terrified masses. Of course, a third great development of this period was conditions in the modern city itself.

Could the terrorism which is so terribly familiar to us today have evolved without the development of the metropolis as we now know it? This seems almost impossible to imagine. Even the terror of the French revolution – Le Terreur – which gives us the modern term terrorism, was most obvious in the centre of Paris where the guillotine sliced heads from a relatively small number of aristocrats in order to strike fear into a much larger number of people.

The history of terrorism is thus the history of our cities. The history of our cities, at least over the last 150 years or so, is in part the history of terrorism. This is a deadly, inextricable link that is unlikely to be broken anytime soon.

Today Saskia Sassen issued her ‘Welcome to a new kind of war: the rise of endless urban conflict‘. She begins with an observation that is scarcely novel:

The traditional security paradigm in our western-style democracies fails to accommodate a key feature of today’s wars: when our major powers go to war, the enemies they now encounter are irregular combatants. Not troops, organised into armies; but “freedom” fighters, guerrillas, terrorists. Some are as easily grouped by common purpose as they are disbanded. Others engage in wars with no end in sight.

What such irregular combatants tend to share is that they urbanise war. Cities are the space where they have a fighting chance, and where they can leave a mark likely to be picked up by the global media. This is to the disadvantage of cities – but also to the typical military apparatus of today’s major powers.

The main difference between today’s conflicts and the first and second world wars is the sharp misalignment between the war space of traditional militaries compared to that of irregular combatants.

Irregular combatants are at their most effective in cities. They cannot easily shoot down planes, nor fight tanks in open fields. Instead, they draw the enemy into cities, and undermine the key advantage of today’s major powers, whose mechanised weapons are of little use in dense and narrow urban spaces.

Advanced militaries know this very well, of course, and urban warfare is now a central medium in military training. Saskia continues:

We have gone from wars commanded by hegemonic powers that sought control over sea, air, and land, to wars fought in cities – either inside the war zone, or enacted in cities far away. The space for action can involve “the war”, or simply specific local issues; each attack has its own grievances and aims, seeking global projection or not. Localised actions by local armed groups, mostly acting independently from other such groups, let alone from actors in the war zone – this fragmented isolation has become a new kind of multi-sited war.

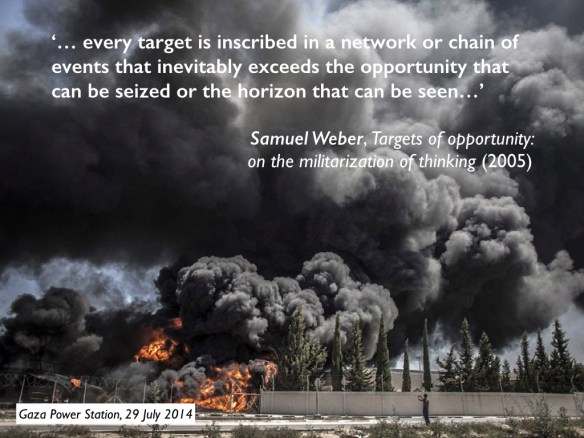

This is, in part, what I tried to capture in my early essay on ‘The everywhere war’, and I’m now busily re-thinking it for my new book. More on this in due course, but it’s worth noting that the Trump maladministration’s National Defense Strategy, while recognising the continuing importance of counter-terrorism and counterinsurgency, has returned the Pentagon’s sights to wars between major powers – notably China and Russia (see also here)– though it concedes that these may well be fought (indeed, are being fought) in part through unconventional means in digital domains. In short, I think later modern war is much more complex than Saskia acknowledges; it has many modalities (which is why I become endlessly frustrated at the critical preoccupation with drones to the exclusion of other vectors of military and paramilitary violence), and these co-exist with – or give a new inflection to – older modalities of violence (I’m thinking of the siege warfare waged by Israel against Gaza or Syria against its own people).

This is, in part, what I tried to capture in my early essay on ‘The everywhere war’, and I’m now busily re-thinking it for my new book. More on this in due course, but it’s worth noting that the Trump maladministration’s National Defense Strategy, while recognising the continuing importance of counter-terrorism and counterinsurgency, has returned the Pentagon’s sights to wars between major powers – notably China and Russia (see also here)– though it concedes that these may well be fought (indeed, are being fought) in part through unconventional means in digital domains. In short, I think later modern war is much more complex than Saskia acknowledges; it has many modalities (which is why I become endlessly frustrated at the critical preoccupation with drones to the exclusion of other vectors of military and paramilitary violence), and these co-exist with – or give a new inflection to – older modalities of violence (I’m thinking of the siege warfare waged by Israel against Gaza or Syria against its own people).

The two contributions I’ve singled out are both broad-brush essays, but Ghaith Abdul-Ahad has contributed a two-part essay on Mosul under Islamic State that is truly brilliant: Part I describes how IS ran the city (‘The Bureaucracy of Evil‘) and Part II how the people of Mosul resisted the reign of terror (‘The Fall‘).

Mosul fell to IS in July 2014, and here is part of Ghaith’s report, where he tells the story of Wassan, a newly graduated doctor:

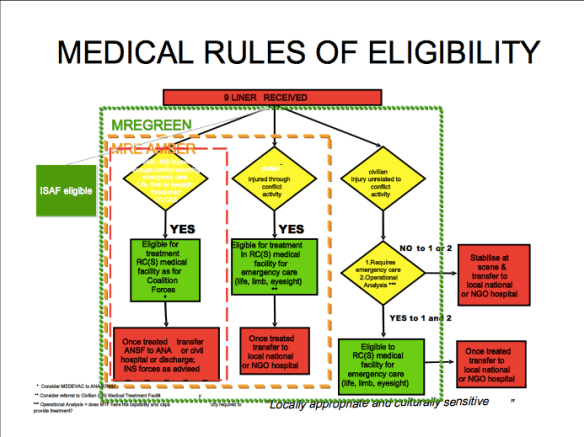

Like many other diwans (ministries) that Isis established in Mosul, as part of their broader effort to turn an insurgency into a fully functioning administrative state, the Diwan al-Siha (ministry of health) operated a two-tier system.There was one set of rules for “brothers” – those who gave allegiance to Isis – and another for the awam, or commoners.

“We had two systems in the hospitals,” Wassan said. “IS members and their families were given the best treatment and complete access to medicine, while the normal people, the awam, were forced to buy their own medicine from the black market.

“We started hating our work. As a doctor, I am supposed to treat all people equally, but they would force us to treat their own patients only. I felt disgusted with myself.”

(Those who openly resisted faced death, but as IS came under increasing military pressure at least one doctor was spared by a judge when he refused to treat a jihadist before a civilian: “They had so few doctors, they couldn’t afford to punish me. They needed me in the hospital.”)

Wassan’s radical solution was to develop her own, secret hospital:

“Before the start of military operations, medicines begun to run out,” she said. “So I started collecting whatever I could get my hands on at home. I built a network with pharmacists I could trust. I started collecting equipment from doctors and medics, until I had a full surgery kit at home. I could even perform operations with full anaesthesia.”

Word of mouth spread about her secret hospital.

“Some people started coming from the other side of Mosul, and whatever medicine I had was running out,” she said. “I knew there was plenty of medicine in our hospital, but the storage rooms were controlled by Isis.

“Eventually, I began to use the pretext of treating one of their patients to siphon medicine from their own storage. If their patient needed one dose, I would take five. After a while they must have realised, because they stopped allowing doctors to go into the storage.”

The punishment for theft is losing a hand. Running a free hospital from her home would have been sedition, punishable by death…

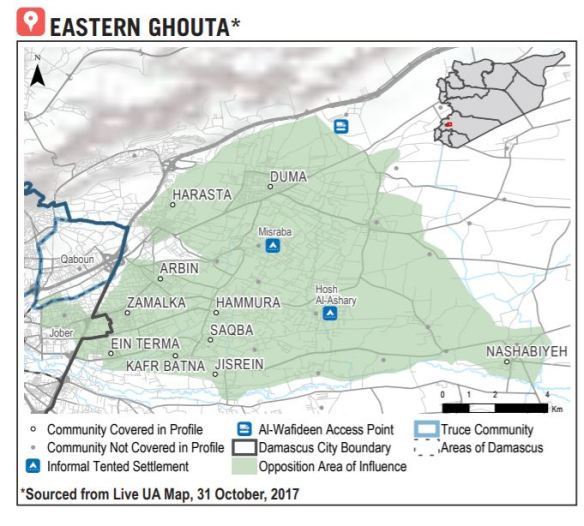

When Wassan’s hospital was appropriated by Isis fighters [this was a common IS tactic – see the image below and the Human Rights Watch report here; the hospital was later virtually destroyed by US air strikes] her secret house-hospital proved essential. More than a dozen births were performed on her dining table; she kicked both brothers out of their rooms to convert them into operating theatres; her mother, an elderly nurse, became her assistant.

As the siege of Mosul by the Iraqi Army ground on, some of the sick and injured managed to run (or stumble) the gauntlet to find medical aid in rudimentary field hospitals beyond the faltering grip of IS, while others managed to make it to major trauma centres like West Irbil.

But for many in Mosul Wassan’s secret hospital was a lifeline (for a parallel story about another woman doctor running a secret clinic under the noses of IS, see here).

Yet there is a vicious sting in the tail:

For Wassan, the ending of Isis rule in Mosul is bittersweet. After many attempts to reach Baghdad to write her board exams for medical school, she was told her work in the hospital for the past three years did not count as “active service”, and she was disqualified.

“The ministry said they won’t give me security clearance because I had worked under Isis administration,” she said.

This, too, is one of the modalities of later modern war – the weaponisation of health care, through selectively withdrawing it from some sections of the population while privileging the access and quality for others. ‘Health care,’ writes Omar Dewachi, ‘has become not only a target but also a tactic of war.’ (If you want to know more about the faltering provision of healthcare and the fractured social fabric of life in post-IS Mosul, I recommend an interactive report from Michael Bachelard and Kate Geraghty under the bleak but accurate title ‘The war has just started‘).

The weaponisation of health care has happened before, of course, and it takes many forms. In 2006, at the height of sectarian violence in occupied Baghdad, Muqtada al-Sadr’s Shi’a militia controlled the Health Ministry and manipulated the delivery of healthcare in order to marginalise and even exclude the Sunni population. As Amit Paley reported:

‘In a city with few real refuges from sectarian violence – not government offices, not military bases, not even mosques – one place always emerged as a safe haven: hospitals…

‘In Baghdad these days, not even the hospitals are safe. In growing numbers, sick and wounded Sunnis have been abducted from public hospitals operated by Iraq’s Shiite-run Health Ministry and later killed, according to patients, families of victims, doctors and government officials.

‘As a result, more and more Iraqis are avoiding hospitals, making it even harder to preserve life in a city where death is seemingly everywhere. Gunshot victims are now being treated by nurses in makeshift emergency rooms set up in homes. Women giving birth are smuggled out of Baghdad and into clinics in safer provinces.’

He described hospitals as ‘Iraq’s new killing fields’, but in Syria the weaponisation of health care has been radicalised and explicitly authorized by the state.

You may think I’ve strayed too far from where I started this post; but I’ve barely moved. For towards the end of her essay Saskia wonders why military and paramilitary violence in cities in so shocking – why it attracts so much more public attention than the millions murdered in the killing fields of the Congo. And she suggests that the answer may lie in its visceral defilement of one of humanity’s greatest potential achievements:

Is it because the city is something we’ve made together, a collective construction across time and space? Is it because at the heart of the city are commerce and the civic, not war?

Lewis Mumford had some interesting things to say about that. I commented on this in ACME several years ago, and while I’d want to flesh out those skeletal remarks considerably now, they do intersect with Saskia’s poignant question about the war on the civic:

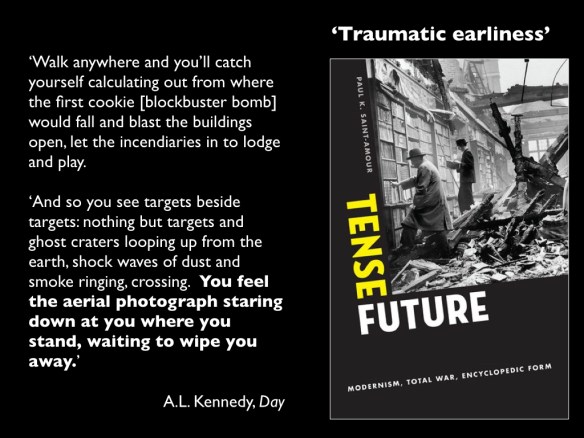

In The Culture of Cities, published just one year before the Second World War broke out, Mumford included ‘A brief outline of hell’ in which he turned the Angelus towards the future to confront the terrible prospect of total war. Raging against what he called the ‘war-ceremonies’ staged in the ‘imperial metropolis’ (‘from Washington to Tokyo, from Berlin to Rome’: where was London, I wonder? Moscow?), Mumford fastened on the anticipatory dread of air war. The city was no longer the place where (so he claimed) security triumphed over predation, and he saw in advance of war not peace but another version of war. Thus the rehearsals for defence (the gas-masks, the shelters, the drills) were ‘the materialization of a skillfully evoked nightmare’ in which fear consumed the ideal of a civilized, cultivated life before the first bombs fell. The ‘war-metropolis’, he concluded, was a ‘non-city’.

After the war, Mumford revisited the necropolis, what he described as ‘the ruins and graveyards’ of the urban, and concluded that his original sketch could not be incorporated into his revised account, The City in History, simply ‘because all its anticipations were abundantly verified.’ He gazed out over the charnel-house of war from the air — Warsaw and Rotterdam, London and Tokyo, Hamburg and Hiroshima — and noted that ‘[b]esides the millions of people — six million Jews alone — killed by the Germans in their suburban extermination camps, by starvation and cremation, whole cities were turned into extermination camps by the demoralized strategists of democracy.’

I’m not saying that we can accept Mumford without qualification, still less extrapolate his claims into our own present, but I do think his principled arc, at once historical and geographical, is immensely important. In now confronting what Stephen Graham calls ‘the new military urbanism’ we need to recover its genealogy — to interrogate the claims to novelty registered by both its proponents and its critics — as a way of illuminating the historical geography of our own present.

It’s about more than aerial violence – though that is one of the signature modalities of modern war – and we surely need to register the heterogeneity and hybridity of contemporary conflicts. But we also need to recognise that they are often not only wars in cities but also wars on cities.

With all these horrors in mind, in my second post I’ll turn to the back-story. You can find other dimensions to the critique of siege warfare in Susan Power, ‘Siege warfare in Syria: prosecuting the starvation of civilians’, Amsterdam Law Forum 8: 2 (2016) 1-22 here or Will Todman, ‘Isolating dissent, punishing the masses: siege warfare as counterinsurgency’, Syria Studies 9 (1) (2017) 1-32.

With all these horrors in mind, in my second post I’ll turn to the back-story. You can find other dimensions to the critique of siege warfare in Susan Power, ‘Siege warfare in Syria: prosecuting the starvation of civilians’, Amsterdam Law Forum 8: 2 (2016) 1-22 here or Will Todman, ‘Isolating dissent, punishing the masses: siege warfare as counterinsurgency’, Syria Studies 9 (1) (2017) 1-32.