I’ve drawn attention to Harry Parker‘s Anatomy of a soldier before: see here and here (and especially ‘Object lessons’: DOWNLOADS tab). Most of the reviews of the novel were highly favourable, applauding Parker’s experimental attempt to tell the story of a soldier seriously wounded by an IED in Afghanistan through the objects with which he becomess entangled.

But writing in The Spectator Louis Amis saw it as an object lesson in ‘How not to tell a soldier’s story‘. He complained that Parker’s device produced a narrative

‘as if the war were composed only of its inanimate processes, either accidental or inevitable. It’s a different planet to the bloody, profane, outlaw Iraq of [Phil] Klay’s Redeployment, radiating shame, PTSD and suicide, and the unbearable awkwardness of transmitting such truths to an alienated civilian world.

Parker’s device gestures aptly towards a spreading out of consciousness, a transmutation, the scattering of the individual along some plane at the threshold of death; the sensations of depersonalisation and hyper-perceptivity associated with traumatic experience; and the soothing quiddity of simple objects, as opposed to abstract thought, for a recovering victim. But it is also a method of averting the gaze from a war’s futility and waste, and worse — and probably, therefore, too, from the true nature of any saving grace.’

I do think Parker’s narrative accomplishes more than Amis allows. It succeeds in making the war in Afghanistan at once strange and familiar; and its strangeness comes not from the people of Afghanistan, that ‘exotic tableau of queerness’ exhibited in so many conventional accounts, but through the activation of objects saturated with the soldier’s sweat, blood and flesh. It’s also instructive to read the novel alongside Jane Bennett‘s Vibrant matter: a political ecology of things or Robert Esposito‘s Persons and things, as I’ve done elsewhere, and to think through the corpo-materialities of modern war and its production of the battle space as an object-space: but neither of these has much to say about how their suggestive ideas might be turned to substantive account.

Still, Amis’s point remains a sharp one; Scottt Beauchamp says something very similar:

Harry Parker goes further than [Tim] O’Brien [in The things they carried] in giving equal narrative play to nonhuman things. Not only do they make the plot of Parker’s novel possible, they also bear semiconscious witness to our shared reality, corroborating it. Their inability to pass moral judgment comes off as a silent accusation. If this ontological shift toward objects is the most honest way we have of talking about war, it’s still limiting: it turned its weakness—its inability to fully articulate the moral significance of war—into a defining characteristic.

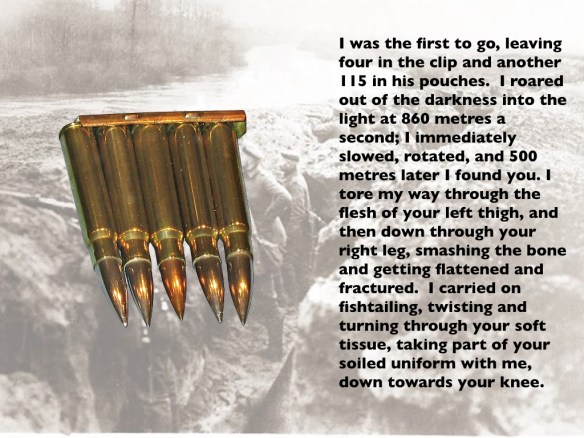

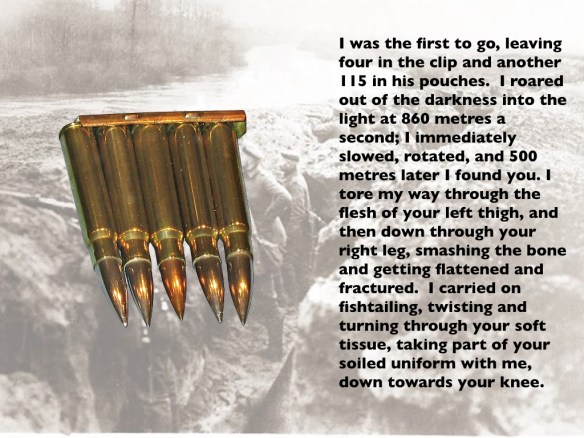

But I haven’t been able to let Parker’s experiment go. So, for one of my presentations in Durham last month – on the parallels and differences between combat medical care and casualty evacuation on the Western Front in the First World War and Afghanistan a century later – I sketched out an Anatomy of another soldier. It’s based on my ongoing archival work; earlier in the presentation I had used diaries, letters, memoirs, sketches and photographs to describe what Emily Mayhew calls the ‘precarious journey’ of British and colonial troops through the evacuation chain – you can see a preliminary version in ‘Divisions of life’ here – so this experiment was a supplement not a substitute. But I wanted to see where it would take me.

So here are the slides; they ought to be self-explanatory – or at any rate, sufficiently clear – but I’ve added some additional notes. I should probably also explain that in each case the object in question appeared on the slide at the end of its associated narrative.

***

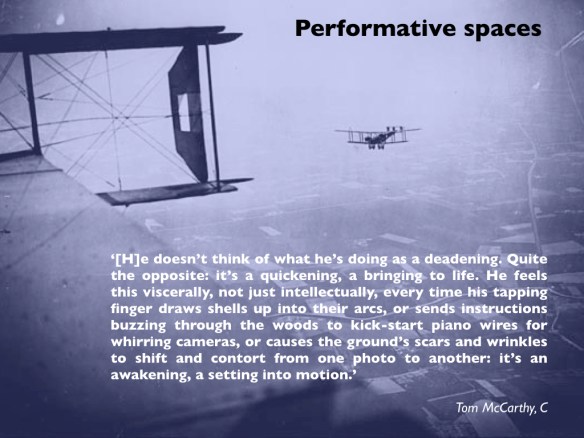

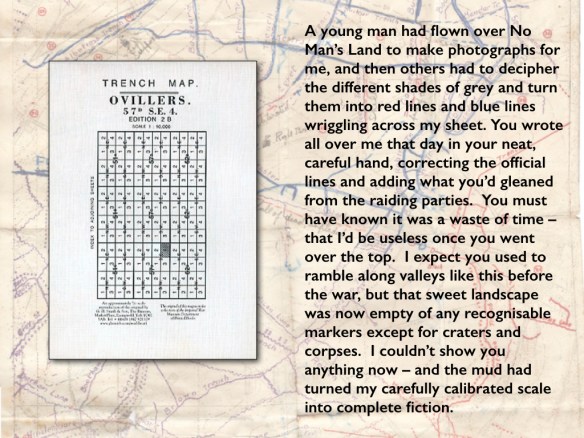

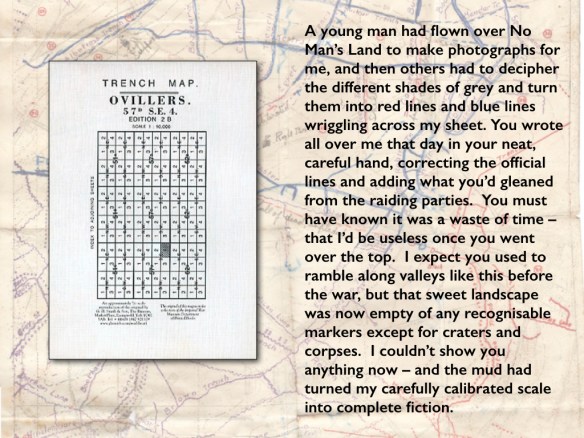

I discuss aerial photography and trench mapping on the Western Front – and the difficulty of navigating the shattered landscapes of trench warfare – in ‘Gabriel’s map: cartography and corpography in modern war’ (DOWNLOADS tab).

You can find a short account of the synchronisation of officers’ watches on the Western Front in ‘Homogeneous (war) time’ here.

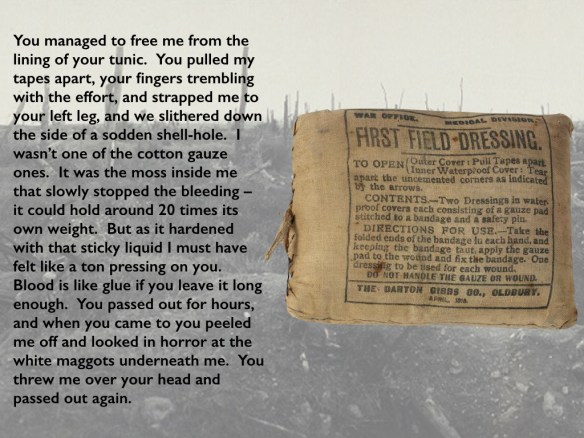

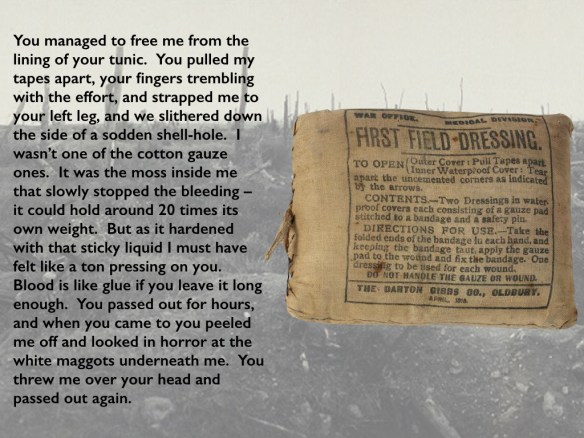

A shortage of cotton (combined with its relatively high cost) together with the extraordinary demand for wound dressings prompted the War Office to use sphagnum moss – the British were years behind the Germans and the French in appreciating its antiseptic and absorbent qualities, which also required dressings to be changed less often. You can get the full story from Peter Ayres, ‘Wound dressing in World War I: the kindly sphagnum moss’, Field Bryology 110 (2013) 27-34 here.

But one RAMC veteran [in ‘Field Ambulance Sketches’, published in 1919] insisted on the restorative power of the white bandage, administered not by regimental stretcher bearers but by the experts of the Royal Army Medical Corps’s Field Ambulance:

The brown first field dressing, admirable as it is from a scientific point of view, always looks a desperate measure; and if it slips, as it generally does on a leg wound, it becomes for the patient merely a depressing reminder of his plight. A clean white dressing, though it may not be nearly so satisfactory in the surgeon’s eyes, seems to reassure a wounded man strangely. It makes him feel that he is being taken care of, gives him a kind of status, and stimulates his sense of personal responsibility. With a white bandage wound in a neat spiral round his leg, he will walk a distance which five minutes earlier, under the dismal suggestion of a first field dressing, he has declared to be utterly beyond his powers.

I borrowed the white maggots (and some of the other details of the wounds) from John Stafford‘s extraordinary, detailed recollection of being wounded on the Somme in August 1916 available here.

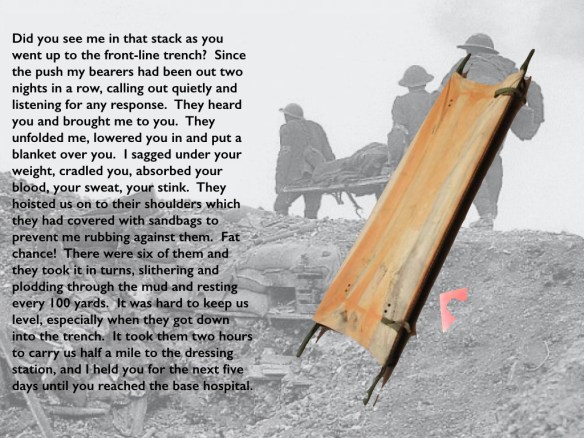

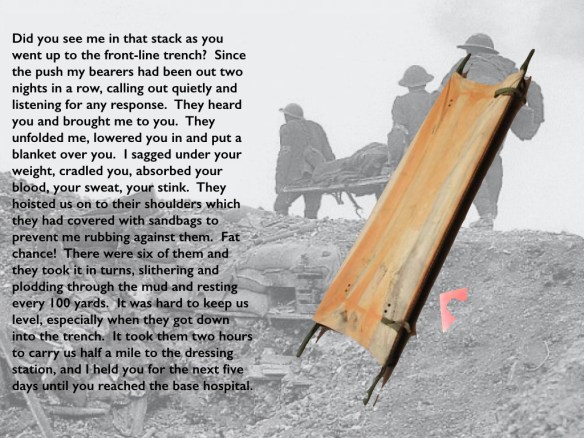

Carrying a stretcher across a mud-splattered, shell-blasted landscape was immensely tiring and it was all too easy to lose one’s bearings. From ‘A stretcher-Bearer’s Diary’, 17 September 1916:

‘The shell fire, and the mud, are simply beyond description, and it is a miracle that any escape being hit. We have to carry the wounded shoulder high, the only way it can be done, because of the mud. Our shoulders are made raw by the chafing of the stretcher handles, although we wear folded sandbags under our shoulder straps. Sweat runs into our eyes, until we can hardly see. When a barrage comes we must keep on and take no notice, as even if we could find cover, there is none for the man on the stretcher….

‘…The rain has made the ground a sea of mud, and we have to carry the wounded three miles to the Dressing Stations, as the wheeled stretchers cannot be used at all. Two men using stretcher slings could not carry a man thirty yards, and I have seen four bearers up to their knees in mud, unable to move without further assistance.

By the time of the 3rd Battle of Ypres, it could take eight men to carry a stretcher half a mile to an aid post – and it could take them two hours to do it.

Even in ideal circumstances, manoeuvering a stretcher down a narrow, crowded trench was extremely difficult, ‘like trying to move a piano down an avenue of turnstiles.’ During major offensives a one-way system was in operation, and stretcher bearers were supposed to use only the ‘down’ trenches. From the Aid Posts the RAMC stretcher-bearers of the Field Ambulance would take over from the regimental stretcher-bearers. Here is one young novice, Private A.F. Young with the 2n3/4th London Field Ambulance:

Step by step we picked our way over the duckboards. It is useless to try and maintain the regulation broken step to avoid swaying the stretcher. Slowly we wind our way along the trenches, our only guide our feet, forcing ourselves through the black wall of night and helped occasionally by the flash of the torch in front. Soon our arms begin to grow tired and the whole weight is thrown on to the slings, which begin to bite into our shoulders; our shoulders sag forward, the sling finds its way on to the back of our necks; we feel half-suffocated. A twelve-stone man, rolled up in several blankets on a stretcher, is no mean load to carry, and on that very first trip we found that the job had little to do with the disciplined stretcher-bearing we had spent so many weary hours practising. We are automatons wound up and propelled by one fixed idea, the necessity of struggling forward. The form on the stretcher makes not a sound; the jolts, the shakings seem to have no effect on him. An injection of morphine has drawn the veil. Lucky for him.

Stretcher-bearers changed – they worked in relays close to the front – but the stretcher remained the same. Ideally the wounded soldier would remain on his stretcher only as far as the Casualty Clearing Station, from where used stretchers would be returned to dressing stations and aid posts by now empty ambulances.

Twelve stretchers were supposed to be kept at every Regimental Aid Post, but supplies could easily run out. When Major Sidney Greenfield was wounded, he remembered:

… the call ‘stretcher-bearers’, ‘stretcher-bearers’, the reply ‘No stretchers’. ‘Find one, it’s an officer.’

And it was not uncommon for those evacuated ‘in a rush’ to remain on their stretcher until the base hospital; and since ambulance trains heading to the coast were less urgent than troop trains and supply trains heading in the opposite direction the journey was usually a slow one. If the nearest hospital turned out to be full, a not uncommon occurrence, the train would be sent on to the next available one, thus prolonging the journey still more.

H.G. Hartnett recalled the sheer pleasure of finally being put to bed at the base hospital at Wimereux:

After being washed and changed into clean pyjamas I was lifted off the stretcher on which I had lain for five days and nights into a soft bed—between sheets.

The contrast, of course, was not only with the canvas stretcher but with sleeping in the trenches wrapped in a groundsheet.

Before the widespread introduction of the Thomas splint (above), ordinary or even improvised splints were used. Here is Sister Kate Luard on board an ambulance train in October 1914:

The compound-fractured femurs were put up with rifles and pick-handles for splints, padded with bits of kilts and straw; nearly all the men had more than one wound – some had ten; one man with a huge compound fracture above the elbow had tied on a bit of string with a bullet in it as a tourniquet above the wound himself.

A fractured femur would turn out to be one of the most common injuries, described by Robert Jones as ‘the tragedy of the war’: if fractures were not properly splinted the soldier would arrive at the Casualty Clearing Station in a state of shock caused by excessive blood loss and pain:

‘These men required radical surgery to save their limbs and lives… Entry and exit wounds would have to be extended widely, removing all dead skin and fat… The bone ends of the femur at the fracture site would then have to be pulled out of the wound and be inspected directly [for loose fragments of bone, clothing and debris]… Wounded soldiers arriving at casualty clearing stations with a weak pulse and low blood pressure secondary to excess blood loss due to inadequately splinted fractures would be unlikely to survive the major procedure’ – let alone the amputations that were often administered.

Mortality rates in such circumstances were around 50 per cent. The Thomas splint was specifically designed to immobilise a fractured femur, and by April/May 1917 its use during the battle of Arras had reduced the mortality rate to 15 per cent, and far fewer men lost their legs: see Thomas Scotland, ‘Developments in orthopaedic surgery’, in Thomas Scotland and Stephen Heys (eds) War surgery 1914-1918.

Stretcher bearers were trained to apply the splint in the field, as in this case, but one senior officer made it clear that in any event it had to be applied no later than the Regimental Aid Post:

The Thomas thigh splint should be applied with the boot and trousers on, the latter being cut at the seam to enable the wound to be dressed. The method of obtaining extension by means of a triangular bandage has been sketched and circulated to all MOs in the Divn. After the splint is adjusted it should be suspended both at the foot and at the ring by two tapes at either end tied to the iron supports one of which is fitted to the stretcher opposite the foot and one opposite the hip.

More information on this truly vital innovation: P.M. Robinson and M. J. O’Meara, ‘The Thomas splint: its origins and use in trauma’, Journal of bone and joint surgery 91 (2009) 540-3: never in my wildest dreams did I imagine reading or referencing such a journal – but it is an excellent and thoroughly accessible account. See for yourself here.

It was vital not to leave a tourniquet on for long. Here is one RAMC officer, Captain Maberly Esler, recalling his service on the Somme in June 1915:

If a limb had been virtually shot off and they were bleeding profusely you could stop the whole thing by putting a tourniquet on, but you couldn’t keep it on longer than an hour without them losing the leg altogether. So it was necessary to get the field ambulance as soon as possible so they could ligature the vessels, and the quicker that was done the better.

Lt Col Henderson‘s pencilled notes on the treatment of the wounded (1916-16) urged stretcher bearers to make every effort to stop bleeding with a compress or bandage: ‘ A tourniquet should only be applied if this response fails and where a tourniquet is applied the [Regimental Medical Officer] should be at once informed on the arrival of the case at the [Regimental Aid Post].’ By May 1916 Medical Officers were being warned ‘against too frequent use of the tourniquet, on the grounds that the dreaded gas bacillus (perfringens) is most likely to thrive in closed tissues.’

A tourniquet could aggravate damaged tissues and did indeed increase the risk of gangrene; 80 per cent of those whose limbs had a tourniquet applied for more than three hours required amputation.

This was a major responsibility; sometimes the card was filled in at a Dressing Station, sometimes at the Casualty Clearing Station. George Carter‘s diary entry for 31 August 1915 explains its importance:

‘My work consists of nailing every patient and getting his number, rank, name, initial, service, service in France, age, religion, battalion and company. That is usually fairly plain sailing, I find, but entails a certain amount of searching [extracting paybook or diary, for example] when a patient is too ill to be bothered with questions. Then I have to find out what is the matter with him, what treatment he has had, and what is going to be done with him… The reason for taking these particulars and making out forms is to prevent any man being lost sight of, whatever happens to him. If he finishes in England after taking a week on the journey, he has got all his partics on him, everywhere he has stopped, the RAMC have been able to see at a glance all about him and can turn up all about him if called on.’

But things could easily go awry. Here is one young soldier, Henry Ogle:

I think it must have been here [at the CCS] that orderlies tied Casualty Labels on our top tunic buttons, and got mine wrong, though it may have been at Louvencourt or even Hébuterne. Wherever it had happened, it was here that I first noticed it and called the attention of an orderly to it. I had been wounded in the right calf by part of a rifle bullet which penetrated deeply and remained in but I had been labelled for superficial something or other, while Frank Wallsgrove was GSW for gunshot wound. I said, ‘Mine’s wrong, for we two were hit by the same bullet.’ ‘Can’t alter your label, chum. Anyhow it doesn’t matter. It’ll get proper attention.’ We were already being packed into a train so nothing could be done and I didn’t worry about it.

At the base hospital he tried again:

An orderly came along (it was then dark night) and threw a nightgown and a towel at me. ‘Bathroom. Down that passage. On the right. Any of them.’ ‘Don’t think I can get there. Can’t walk.’ ‘Let’s see your label.’ ‘Label’s wrong.’ ‘What do you know about that? Go on.’ ‘I know a bloody sight more about it than you do, chum, but I’ll see what I can do.’ It was not easy as the leg was quite out of action and my orderly friend had no time to watch… On crawling back I found Frank tucked into bed. Our case-sheets were clipped to boards which hung on the wall behind our beds and, so far, the items from our tunic labels had been copied out on the case-sheets. The next morning the customary round of visits was made by the Medical Officer on duty with Matron and Sister of Ward and an orderly or two. I tried to explain that my label was wrong and Frank backed me up but we were simply ignored. My wound was dressed as a surface wound.

It was only after the swelling of his leg alarmed Matron that Henry was shipped off for an X-ray that revealed the need for an operation to remove the bullet.

‘T’ for anti-tetanus serum. In the first weeks of the war tetanus threatened to become a serious problem: on 19 October 1915 Sister Kate Luard recorded ‘a great many deaths from tetanus’ in her diary, but two months later she was able to note ‘The anti-tetanus serum injection that every wounded man gets with his first dressing has done a great deal to keep the tetanus under.’ In A Surgeon in Khaki, published in 1915, Arthur Andersen Martin confirmed that ‘every man wounded in France or Flanders today gets an injection of this serum within twenty-four hours of the receipt of the wound’ – at least, if he had been recovered in that time – and ‘no deaths from tetanus have occurred since these measures were adopted.’

More information: Peter Cornelis Wever and Leo van Bergen, ‘Prevention of tetanus during the First World War’, Medical Humanities 38 (2012) 78-82.

Morphine was administered for pain relief, but it still awaits its medical-military historian (unless I’ve missed something).

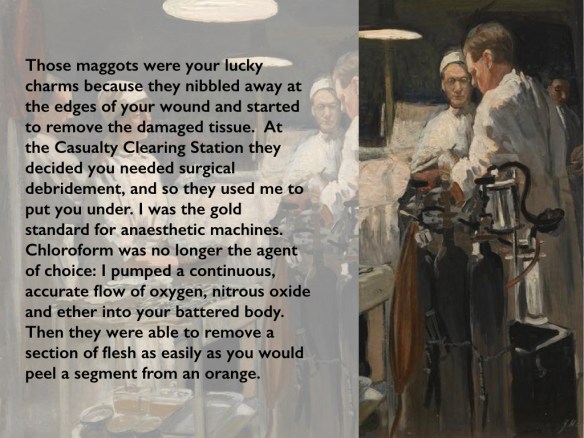

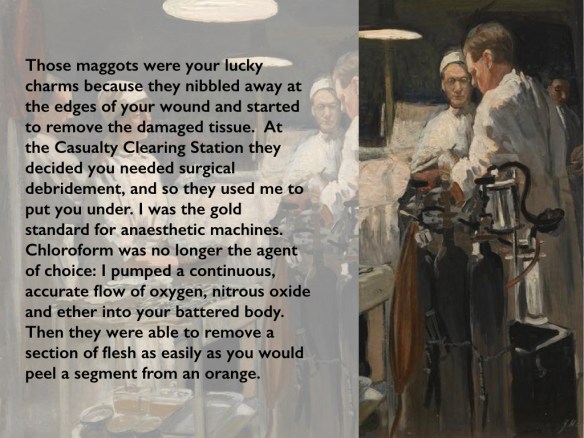

This was Boyle’s anaesthetic apparatus, but before the widespread availability of these machines a variety of systems was in use and, in the heat of the moment, the administration of anaesthesia was often far removed from the clinical, calibrated procedures the machine made possible. Here is a chaplain who served at No 44 Casualty Clearing Station:

I spent most of my time giving anaesthetics. I had no right to be doing this, of course, but we were simply so rushed. We couldn’t get the wounded into the hospital quickly enough, and the journey from the battlefield was terrible for these poor lads. It was a question of operating as quickly as possible. If they had had to wait their turn in the normal way, until the surgeon was able to perform an operation with another doctor giving the anaesthetic, it would have been too late for many of them. As it was, many died.

The most fortunate patients were those who had little or no recollection of the procedure. Here is H.G. Hartnett on his experience at No 15 Casualty Clearing Station (the second occasion he was wounded):

I was destined for surgery and lay in agony on my stretcher until near 9.00 pm, when orderlies carried me into a brilliantly lit operating theatre. I was placed on the centre one of three operating tables where I lay watching doctors and nurses completing an operation on another patient only a few feet from where I lay. When my turn came my wound was uncovered and a doctor placed a mask over my face. Then he asked me the name of the colonel of my battalion as he administered the anaesthetic. I remember no more about the operation or the theatre. When I returned to brief consciousness about 4.00 am the next morning I was lying on a stretcher on the ground in a large canvas marquee, in the third position on my side of it. Others had been carried in during the night, all from the operating theatre. The fumes of the anaesthetic from their clothes and blankets continued to put us off to sleep again. The day was well advanced when I finally returned to full consciousness.

In the early years of the war anaesthesia was not a recognised speciality – and chloroform was the most widely used agent – but as the tide of wounded surged, operative care became more demanding and Casualty Clearing Stations assumed an increasing operative load so it became necessary to refine both its application and the skills of those who administered it. In the British Army advances in anaesthesia were pioneered by Captain Geoffrey Marshall at No 17 Casualty Clearing Station at Remy Siding near Ypres from 1915. By then nitrous oxide and oxygen were commonly used for short operations (which did not mean they were minor: they included guillotine amputations) but longer procedures typically relied on chloroform and ether. A crucial disadvantage of chloroform was that it lowered blood pressure in patients who had often already lost a lot of blood. ‘If chloroform be used,’ Marshall warned, ‘the patient’s condition will deteriorate during the administration, and he will not rally afterwards.’ And while ether would often produce an improvement during the operation, this was typically temporary: ‘the after-collapse [would be] more profound and more often fatal.’ His achievement was to show that a combination of nitrous oxide, oxygen and ether significantly improved survival rates for complex procedures – from 10 per cent to 75 per cent for leg amputations – and to have a machine made to regulate the combination of the three agents. His design was copied and modified by Captain Henry Boyle, whose name became attached to the device.

More information: Geoffrey Marshall, ‘The administration of anaesthetics at the front’, in British medicine in the war, 1914-1917; N.H. Metcalfe, ‘The effect of the First World War (1914-1918) on the development of British anaesthesia’, European Journal of Anaesthesiology 24 (2007) 649-57; E. Ann Robertson, ‘Anaesthesia, shock and resuscitation’, in Thomas Scotland and Steven Heys (eds) War surgery, 1914-1918.

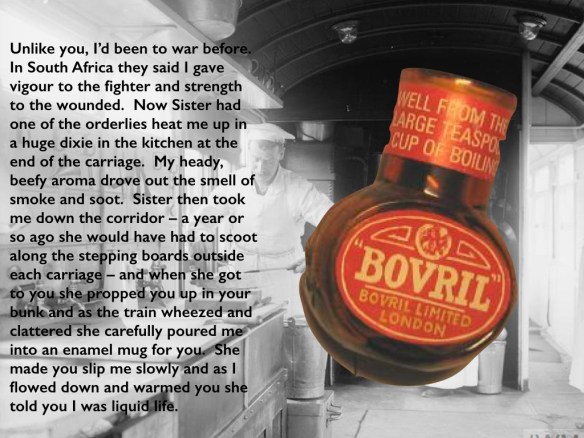

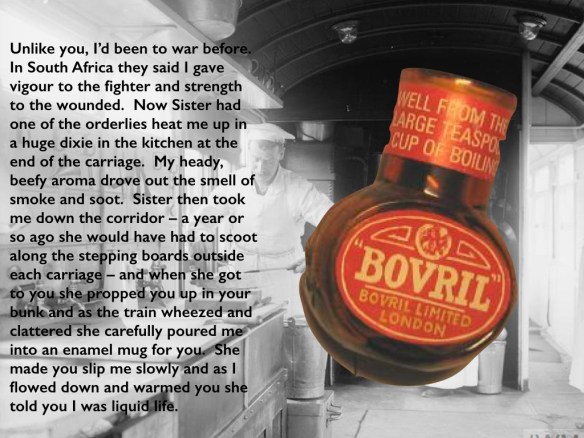

Bovril was advertised in all these ways; the company used a sketch of the Gallipoli campaign to claim that Bovril would ‘give strength to win’ and that it was a ‘bodybuilder of astonishing power’. In 1916 the company even published an extract from a letter purported to come from the Western Front, accompanied by an image of an RAMC Field Ambulance tending a wounded soldier:

But for a plentiful supply of Bovril I don’t know what we should have done. During Neuve Chapelle and other engagements we had big cauldrons going over log fires, and as we collected and brought in the wounded we gave each man a good drink of hot Bovril and I cannot tell you how grateful they were.

Oxo seems to have been less popular, and least for any supposed medicinal or restorative properties, but it was often sent to soldiers by their families at home. One advertising campaign enjoined them to ‘be sure to send Oxo’, and in one ad a Tommy writes home to say that when he returned to his billet to find the parcel, ‘the first thing I did was to make a cup of OXO and I and my chums declared on the spot this cup of OXO was the best drink we had ever tasted.’

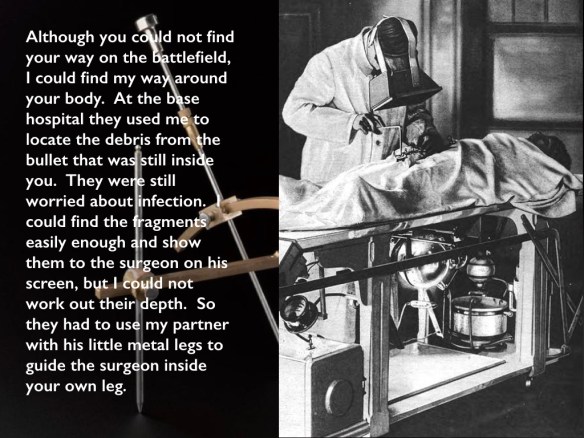

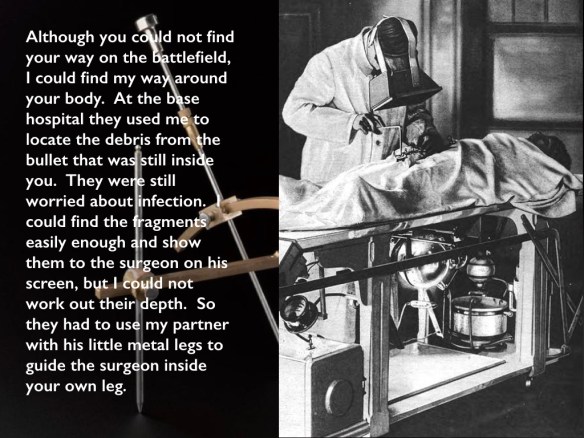

The image shows a surgeon using a fluoroscope to locate the fragments of the bullet:

An early Crookes x-ray tube visible under the table emits a beam of x-rays vertically through the patient’s body. The surgeon wears a large fluoroscope on his face, a screen coated with a fluorescent chemical such as calcium tungstate which glows when x-rays strike it. The x-ray image of the patient’s body appears on the screen, with the bullet fragments appearing dark.

The ‘partner’ referred to was the Hirtz compass (visible on the left of the image). According to one standard military-medical history:

The essential feature of the H[i]rtz compass is the possibility of adjustment of the movable legs that support the instrument, so that when resting on fixed marks on the body of the patient the foreign body will be at the center of asphere, a meridian arc of which is carried by the compass. This arc is capable of adjustment in any position about a central axis. An indicating rod passes through a slider attached to the movable arc in such a way as to coincide in all positions with a radius of the sphere, and whether it actually reaches the center or not it is always directed toward that point. If its movement to the center of the sphere is obstructed by the body of the patient, the amount it lacks of reaching the center will be the depth of the projectile in the direction indicated by the pointer.

The value of the compass lies in its wide possibility as a surgical guide, in that it does not confine the attention of the surgeon to a single point marked on the skin, with a possible uncertainty as to the direction in which he should proceed in order to reach the projectile, but gives him a wide latitude of approach and explicit information as to depth in a direction of his own selection.

The compass built on Gaston Contremoulins‘ attempts at ‘radiographic stereotaxis’; it could usually locate foreign objects to within 1-2 mm: much more than you could possibly want here.

The reassuring scientificity of all this is tempered by a cautionary observation from a wounded officer, Major Sidney Greenfield, who was X-rayed at a Casualty Clearing Station:

My next recollection was the x-ray machine and two young fellows who were operating it. Apparently the operator had been killed the previous night by a bomb on the site and these two were standing in with little or no experience of an x-ray machine. Their conversation was far from encouraging and was roughly like this: ‘Now we have got to find where it is … is it this knob?’ ‘No.’ ‘Try that one.’ ‘Try turning that one.’ ‘No, that doesn’t seem to be right.’ ‘Ah, There it is.’ ‘Where’s the pencil. We must mark where it is. Now we have to find out how deep it is.’ After some time they seemed to be satisfied. In my condition and knowing little about electrical machines such as x-ray I wondered whether I should be electrocuted and was more relaxed when I was taken back to bed.

Incidentally, X-rays were called Roentgen rays (after the scientist Wilhelm Roentgen who discovered them in 1895) but the British antipathy towards all things German saw them re-named ‘X-rays’ from 1915: Alexander MacDonald, ‘X-Rays during the Great War’, in Thomas Scotland and Steven Heys (eds) War surgery, 1914-1918.

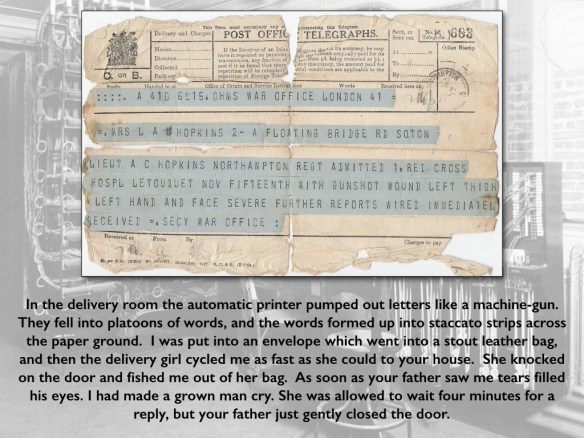

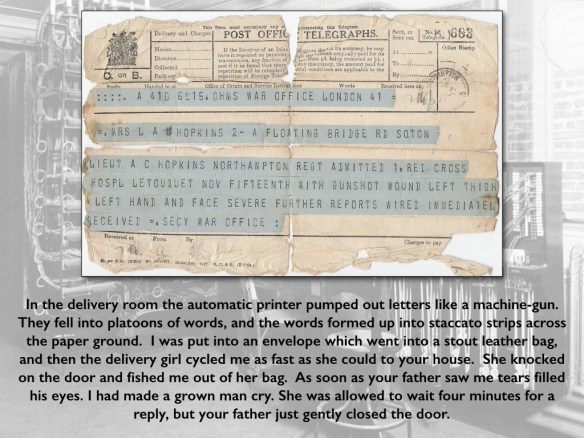

In addition to these terse communications, nurses and chaplains usually wrote to relatives on behalf of their patients. It was seen as a sacred duty, but it often seemed to be a never-ending task. On 1 August 1917 Sister Kate Luard confided in her diary: ‘I don’t see how the “break-the-news” letters are going to be written, because the moment for sitting down literally never comes from 7 a.m. to midnight.’ In the case shown here, Sister Kathleen Mary Latham had written to Lt Hopkins’s wife on 12 November 1917 from a Casualty Clearing Station to say that

‘your husband has been brought to this hospital with wounds of the legs, arms, hand and face. He has had an operation and is going on well. Unfortunately it was found necessary to remove the left eye as it was badly damaged, but he can see with the other though the lid is swollen and he cannot use it yet. No bones are broken. It will not be advisable for you to write to this address as he will probably be going on to the base in a day or two.’

The telegram from the War Office is dated three days later, by which time Hopkins had reached the base hospital at Le Touquet. Sister Latham’s earlier account of her work at Casualty Clearing Station No. 3 at Poperinghe in 1915 is here.

***

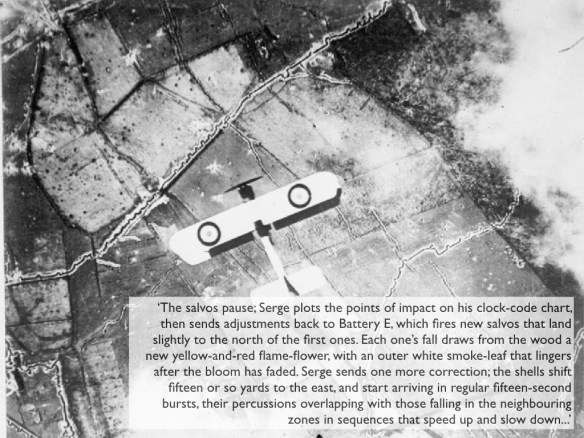

In Durham, Louise Amoore pressed me on the anthropomorphism that seems inescapable in a narrative like this; it worries me too (I’ve always been leery of Bruno Latour‘s Aramis for that very reason). I tried removing the ‘I’ and substituting an ‘it’ but I found doing so destroyed both the operative agency of the objects and, perhaps more important, the transient, enforced intimacy between them and the soldier’s body. That intimacy was more than physical, I think. I’ve already cited the reassurance provided by the prick of a needle, the whiteness of a new bandage; but the mundanity of objects could also be disorientating, intensifying an already intense sur-reality. Here, for example, is Gabriel Chevallier recalling the moment when he and his comrades went over the top:

The feeling of being suddenly naked, the feeling that there is nothing to protect you. A rumbling vastness, a dark ocean with waves of earth and fire, chemical clouds that suffocate. Through it can be seen ordinary, everyday objects, a rifle, a mess tin, ammunition belts, a fence post, inexplicable presences in this zone of unreality.

Aramis also alerted me to another, and perhaps even more debilitating dilemma: a latent functionalism in which everything that is pressed into service works to carry the soldier through the evacuation chain. That seems unavoidable in a narrative whose telos is precisely the base hospital and Blighty beyond. Yet we know that, for all the Taylorist efficiency that was supposed to orchestrate the evacuation system in this profoundly industrial war, in many cases the chain was broken, another life was lost or permanently, devastatingly transformed. As you can see, I’ve tried to do something about that with some of the objects I’ve selected.

I’ll probably add more objects: this is very much a work in progress, and I’m not sure where it will go – so as always, I’d welcome any constructive comments or suggestions. Any written version would involve longer descriptions, I think, and would probably dispense with most of the scaffolding of notes I’ve erected here (though some of it could and probably should be incorporated into the descriptions).

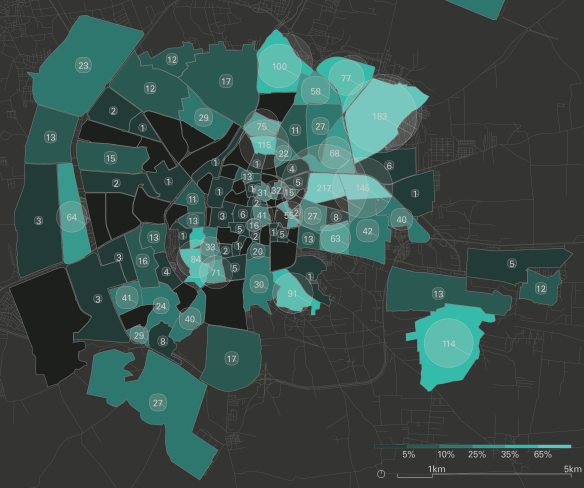

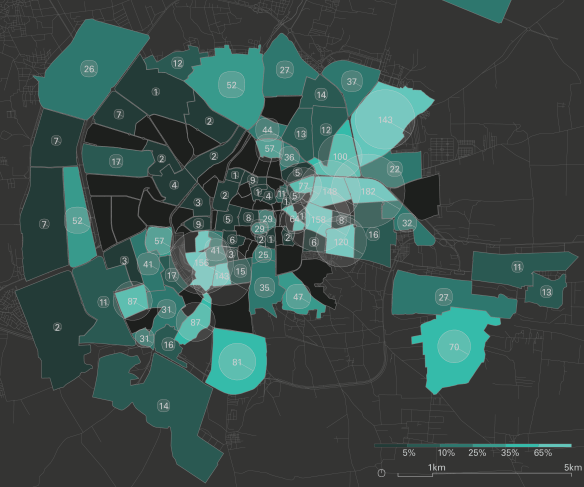

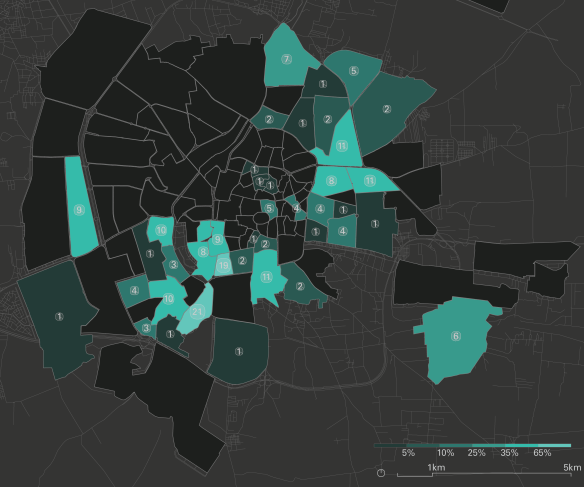

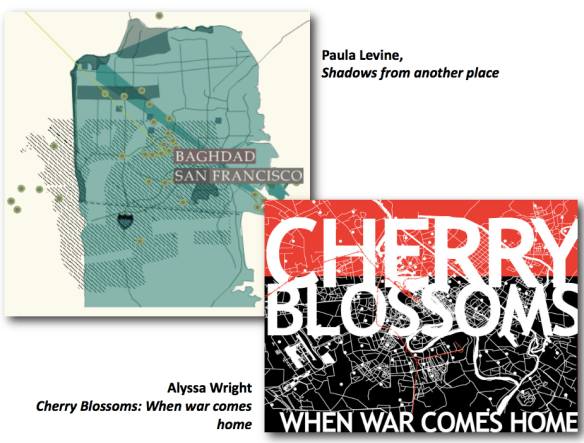

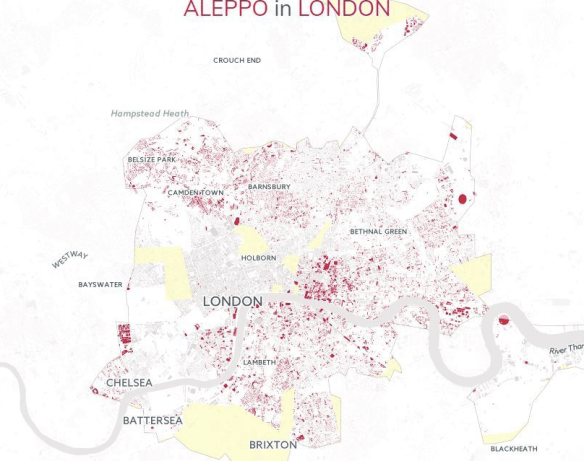

That last phrase is an echo of Laura’s book, Close Up at a Distance: Mapping, Technology and Politics, published by MIT in 2013. The new project emerged out of a seminar taught by Laura in 2016:

That last phrase is an echo of Laura’s book, Close Up at a Distance: Mapping, Technology and Politics, published by MIT in 2013. The new project emerged out of a seminar taught by Laura in 2016: