Next month I’ll be in Sweden and the UK doing all sorts of things – one of them is an updated presentation of my arguments about attacks on hospitals, medical workers and patients in Afghanistan and Syria. Here’s the poster for its outing in Cambridge on 6 March, and – given my commentary on Meatspace? – I’m very much looking forward to Lauren Wilcox‘s response and a lively conversation afterwards.

Category Archives: Afghanistan

Meatspace?

In Lucy Suchman‘s marvellous essay on ‘Situational Awareness’ in remote operations she calls attention to what she calls bioconvergence:

A corollary to the configuration of “their” bodies as targets to be killed is the specific way in which “our” bodies are incorporated into war fighting assemblages as operating agents, at the same time that the locus of agency becomes increasingly ambiguous and diffuse. These are twin forms of contemporary bioconvergence, as all bodies are locked together within a wider apparatus characterized by troubling lacunae and unruly contingencies.

In the wake of her work, there has been a cascade of essays insisting on the embodiment of air strikes carried out by Predators and Reapers – the bodies of the pilots, sensor operators and the legion of others who carry out these remote operations, and the bodies of their victims – and on what Lauren Wilcox calls the embodied and embodying nature of drone warfare (‘Embodying algorithmic war: Gender, race, and the posthuman in drone warfare’ in Security dialogue, 2016; see also Lorraine Bayard de Volo, ‘Unmanned? Gender recalibrations and the rise of drone warfare’, Politics and gender, 2015). Lauren distinguishes between visual, algorithmic and affective modes of embodiment, and draws on the transcript of what has become a canonical air strike in Uruzgan province (Afghanistan) on 21 February 2010 to develop her claims (more on this in a moment).

And yet it’s a strange sort of embodying because within the targeting process these three registers also produce an estrangement and ultimately an effacement. The corporeal is transformed into the calculative: a moving target, a data stream, an imminent threat. If this is still a body at all, it’s radically different from ‘our’ bodies. As I write these words, I realise I’m not convinced by the passage in George Brant‘s play Grounded in which the face of a little girl on the screen, the daughter of a ‘High Value Target’, becomes the face of the Predator pilot’s own daughter. For a digital Orientalism is at work through those modes of embodiment that interpellates those watching as spectators of what Edward Said once called ‘a living tableau of queerness’ that in so many cases will become a dead tableau of bodies which remain irredeemably Other.

There is a history to the embodiment of air strikes, as my image above shows. Aerial violence in all its different guises has almost invariably involved an asymmetric effacement. The lives – and the bodies – of those who flew the first bombing missions over the Western Front in the First World War; the young men who sacrificed their lives during the Combined Bomber Offensive in the Second World War; and even the tribulations and traumas encountered by the men and women conducting remote operations over Afghanistan and elsewhere have all been documented in fact and in fiction.

And yet, while others – notably social historians, investigative journalists and artists – have sought to bring into view the lives shattered by aerial violence, its administration has long mobilised an affective distance between bomber and bombed. As I showed in ‘Doors into nowhere’ and ‘Lines of descent’ (DOWNLOADS tab), the bodies of those crouching beneath the bombs are transformed into abstract co-ordinates, coloured lights and target boxes. Here is Charles Lindbergh talking about the air war in the Pacific in May 1944:

You press a button and death flies down. One second the bomb is hanging harmlessly in your racks, completely under your control. The next it is hurtling through the air, and nothing in your power can revoke what you have done… How can there be writhing, mangled bodies? How can this air around you be filled with unseen projectiles? It is like listening to a radio account of a battle on the other side of the earth. It is too far away, too separated to hold reality.

Or Frank Musgrave, a navigator with RAF Bomber Command, writing about missions over Germany that same year:

These German cities were simply coordinates on a map of Europe, the first relatively near, involving around six hours of flying, the second depressingly distant, involving some eight or nine hours of flying. Both sets of coordinates were at the centre of areas shaded deep red on our maps to indicate heavy defences. For me ‘Dortmund’ and ‘Leipzig’ had no further substance or concrete reality.

Harold Nash, another navigator:

It was black, and then suddenly in the distance you saw lights on the floor, the fires burning. As you drew near, they looked like sparkling diamonds on a black satin background… [T]hey weren’t people to me, just the target. It’s the distance and the blindness which enabled you to do these things.

One last example – Peter Johnson, a Group Captain who served with distinction with RAF Bomber Command:

Targets were now marked by the Pathfinder Force … and these instructions, to bomb a marker, introduced a curiously impersonal factor into the act of dropping huge quantities of bombs. I came to realize that crews were simply bored by a lot of information about the target. What concerned them were the details of route and navigation, which colour Target Indicator they were to bomb… In the glare of searchlights, with the continual winking of anti-aircraft shells, the occasional thud when one came close and left its vile smell, what we had to do was search for coloured lights dropped by our own people, aim our bombs at them and get away.

The airspace through which the bomber stream flew was a viscerally biophysical realm, in which the crews’ bodies registered the noise of the engines, the shifts in course and elevation, the sound and stink of the flak, the abrupt lift of the aircraft once the bombs were released. They were also acutely aware of their own bodies: fingers numbed by the freezing cold, faces encased in rubbery oxygen masks, and frantic fumblings over the Elsan. But the physicality of the space far below them was reduced to the optical play of distant lights and flames, and the crushed, asphyxiated and broken bodies appeared – if they appeared at all – only in their nightmares.

These apprehensions were threaded into what I’ve called a ‘moral economy of bombing’ that sought (in different ways and at different times) to legitimise aerial violence by lionising its agents and marginalising its victims (see here: scroll down).

But remote operations threaten to transform this calculus. Those who control Predators and Reapers sit at consoles in air-conditioned containers, which denies them the physical sensations of flight. Yet in one, as it happens acutely optical sense they are much closer to the devastation they cause: eighteen inches away, they usually say, the distance from eye to screen. And the strikes they execute are typically against individuals or small groups of people (rather than objects or areas), and they rely on full-motion video feeds that show the situation both before and after in detail (however imperfectly). Faced with this highly conditional intimacy, as Lauren shows, the bodies that appear in the cross-hairs are produced as killable bodies through a process of somatic abstraction – leaving the fleshy body behind – that is abruptly reversed once the missile is released.

Thus in the coda to the original version of ‘Dirty Dancing’ (DOWNLOADS tab) – and which I’ve since excised from what was a very long essay; reworked, it will appear in a revised form as ‘The territory of the screen’ – I described how

intelligence agencies produce and reproduce the [Federally Administered Tribal Areas in Pakistan] as a data field that is systematically mined to expose seams of information and selectively sown with explosives to be rematerialised as a killing field. The screens on which and through which the strikes are animated are mediations in an extended sequence in which bodies moving into, through and out from the FATA are tracked and turned into targets in a process that Ian Hacking describes more generally as ‘making people up’: except that in this scenario the targets are not so much ‘people’ as digital traces. The scattered actions and interactions of individuals are registered by remote sensors, removed from the fleshiness of human bodies and reassembled as what Grégoire Chamayou calls ‘schematic bodies’. They are given codenames (‘Objective x’) and index numbers, they are tracked on screens and their danse macabre is plotted on time-space grids and followed by drones. But as soon as the Hellfire missiles are released the transformations that have produced the target over the preceding weeks and months cascade back into the human body: in an instant virtuality becomes corporeality and traces turn into remains.

There are two difficulties in operationalising that last sentence. One is bound up with evidence – and in particular with reading what Oliver Kearns calls the ‘residue’ of covert strikes (see his ‘Secrecy and absence in the residue of covert drone strikes’, Political Geography, 2016) – and the other is one that I want to address here.

To do so, let me turn from the FATA to Yemen. The Mwatana Organisation for Human Rights in Sa’ana has released a short documentary, Waiting for Justice, that details the effects of a US drone strike on civilians:

If the embedded version doesn’t work, you can find it on YouTube.

At 6 a.m. on 19 April 2014 a group of men – mainly construction workers, plus one young father hitching a ride to catch a bus into Saudi Arabia – set off from from their villages in al-Sawma’ah to drive to al-Baidha city; 20 to 30 metres behind their Toyota Hilux, it turned out, was a Toyota Land Cruiser carrying suspected members of Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula.

That car was being tracked by a drone: it fired a Hellfire missile, striking the car and killing the occupants, and shrapnel hit the Hilux. Some of the civilians sought refuge in an abandoned water canal, when the drone (or its companion) returned for a second strike.

Four of them were killed – Sanad Hussein Nasser al-Khushum (30), Yasser Abed Rabbo al-Azzani (18), Ahmed Saleh Abu Bakr (65) and Abdullah Nasser Abu Bakr al-Khushu – and five were injured: the driver, Nasser Mohammed Nasser (35), Abdulrahman Hussein al-Khushum (22), Najib Hassan Nayef (35 years), Salem Nasser al-Khushum (40) and Bassam Ahmed Salem Breim (20).

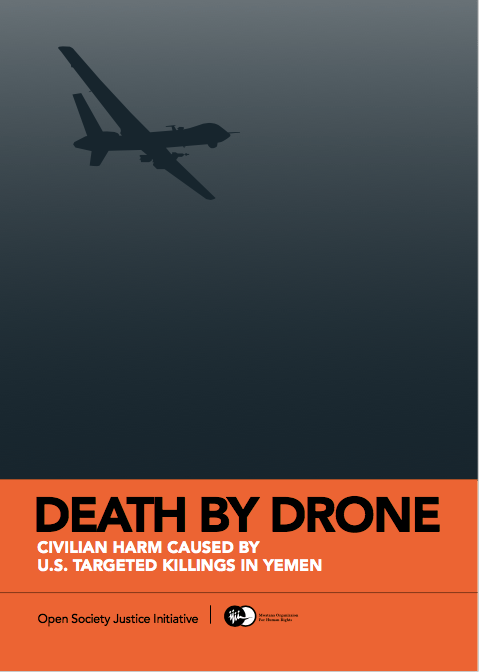

The film draws on Death by Drone: civilian harm caused by US targeted killing in Yemen, a collaborative investigation carried out by the Open Society Justice Initiative in the United States and Mwatana in Yemen into nine drone strikes: one of them (see pp. 42-48) is the basis of the documentary; the strike is also detailed by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism as YEM159 here.

That report, together with the interview and reconstruction for the documentary, have much to tell us about witnesses and residues.

In addition the father of one of the victims, describing the strike in the film, says ‘They slaughter them like sheep‘…

… and, as Joe Pugliese shows in a remarkable new essay, that phrase contains a violent, visceral truth.

Joe describes a number of other US strikes in Yemen – by cruise missiles and by Hellfire missiles fired from drones (on which see here; scroll down) – in which survivors and rescuers confronted a horrific aftermath in which the incinerated flesh of dead animals and the flesh of dead human beings became indistinguishable. This is a radically different, post-strike bioconvergence that Joe calls a geobiomorphology:

The bodies of humans and animals are here compelled to enflesh the world through the violence of war in a brutally literal manner: the dismembered and melted flesh becomes the ‘tissue of things’ as it geobiomorphologically enfolds the contours of trees and rocks. What we witness in this scene of carnage is the transliteration of metadata algorithms to flesh. The abstracting and decorporealising operations of metadata ‘without content’ are, in these contexts of militarised slaughter of humans and animals, geobiomorphologically realised and grounded in the trammelled lands of the Global South.

Indeed, he’s adamant that it is no longer possible to speak of the corporeal in the presence of such ineffable horror:

One can no longer talk of corporeality here. Post the blast of a drone Hellfire missile, the corpora of animals-humans are rendered into shredded carnality. In other words, operative here is the dehiscence of the body through the violence of an explosive centripetality that disseminates flesh. The moment of lethal violence transmutes flesh into unidentifiable biological substance that is violently compelled geobiomorphologically to assume the topographical contours of the debris field.

By these means, he concludes,

the subjects of the Global South [are rendered] as non-human animals captivated in their lawlessness and inhuman savagery and deficient in everything that defines the human-rights-bearing subject. In contradistinction to the individuating singularity of the Western subject as named person, they embody the anonymous genericity of the animal and the seriality of the undifferentiated and fungible carcass. As subjects incapable of embodying the figure of “the human,” they are animals who, when killed by drone attacks, do not die but only come to an end.

You can read the essay, ‘Death by Metadata: The bioinformationalisation of life and the transliteration of algorithms to flesh’, in Holly Randell-Moon and Ryan Tippet (eds) Security, race, biopower: essays on technology and corporeality (London: Palgrave, 2016) 3-20.

It’s an arresting, truly shocking argument. You might protest that the incidents described in the essay are about ordnance not platform – that a cruise missile fired from a ship or a Hellfire missile fired from an attack helicopter would produce the same effects. And so they have. But Joe’s point is that where Predators and Reapers are used to execute targeted killings they rely on the extraction of metadata and its algorithmic manipulation to transform individualised, embodied life into a stream of data – a process that many of us have sought to recover – but that in the very moment of execution those transformations are not simply, suddenly reversed but displaced into a generic flesh. (And there is, I think, a clear implication that those displacements are pre-figured in the original de-corporealisation – the somatic abstraction – of the target).

Joe’s discussion is clearly not intended to be limited to those (literal) instances where animals are caught up in a strike; it is, instead, a sort of limit-argument designed to disclose the bio-racialisation of targeted killing in the global South. It reappears time and time again. Here is a sensor operator, a woman nicknamed “Sparkle”, describing the aftermath of a strike in Afghanistan conducted from Creech Air Force Base in Nevada:

Sparkle could see a bunch of hot spots all over the ground, which were likely body parts. The target was dead, but that isn’t always the case. The Hellfire missile only has 12 pounds of explosives, so making sure the target is in the “frag pattern,” hit by shrapnel, is key.

As the other Reaper flew home to refuel and rearm, Spade stayed above the target, watching as villagers ran to the smoldering motorbike. Soon a truck arrived. Spade and Sparkle watched as they picked up the target’s blasted body.

“It’s just a dead body,” Sparkle said. “I grew up elbows deep in dead deer. We do what we needed to do. He’s dead. Now we’re going to watch him get buried.”

The passage I’ve emphasised repeats the imaginary described by the strike survivor in Yemen – but from the other side of the screen.

Seen thus, Joe’s argument speaks directly to the anguished question asked by one of the survivors of the Uruzgan killings in Afghanistan:

How can you not identify us? (The question – and the still above – are taken from the reconstruction in the documentary National Bird). We might add: How do you identify us? These twin questions intersect with a vital argument developed by Christiane Wilke, who is deeply concerned that civilians now ‘have to establish, perform and confirm their civilianhood by establishing and maintaining legible patterns of everyday life, by conforming to gendered and racialized expectations of mobility, and by not ever being out of place, out of time’ (see her chapter, ‘The optics of war’, in Sheryl Hamilton, Diana Majury, Dawn Moore, Neil Sargent and Christiane Wilke, eds., Sensing Law [2017] pp 257-79: 278). As she wrote to me:

I’m really disturbed by the ways in which the burden of making oneself legible to the eyes in the sky is distributed: we don’t have to do any of that here, but the people to whom we’re bringing the war have to perform civilian-ness without fail.

Asymmetry again. Actors required to perform their civilian-ness in a play they haven’t devised before an audience they can’t see – and which all too readily misunderstands the plot. And if they fail they become killable bodies.

But embodying does not end there; its terminus is the apprehension of injured and dead bodies. So let me add two riders to the arguments developed by Lauren and Joe. I’ll do so by returning to the Uruzgan strike.

I should say at once that this is a complicated case (see my previous discussions here and here). In the early morning three vehicles moving down dusty roads and tracks were monitored for several hours by a Predator controlled by a flight crew at Creech Air Force Base in Nevada; to the south a detachment of US Special Forces was conducting a search operation around the village of Khod, supported by Afghan troops and police; and when the Ground Force Commander determined that this was a ‘convoy’ of Taliban that posed a threat to his men he called in an air strike executed by two OH-58 attack helicopters that killed 15 or 16 people and wounded a dozen others. All of the victims were civilians. This was not a targeted killing, and there is little sign of the harvesting of metadata or the mobilisation of algorithms – though there was some unsubstantiated talk of the possible presence of a ‘High-Value Individual’ in one of the vehicles, referred to both by name and by the codename assigned to him on the Joint Prioritised Effects List, and while the evidence for this seems to have been largely derived from chatter on short-wave radios picked up by the Special Forces on the ground it is possible that a forward-deployed NASA team at Bagram was also involved in communications intercepts. Still, there was no geo-locational fixing, no clear link between these radio communications and the three vehicles, and ultimately it was the visual construction of their movement and behaviour as a ‘hostile’ pattern of life that provoked what was, in effect, a signature strike. But this was not conventional Close Air Support either: the Ground Force Commander declared first a precautionary ‘Air TIC’ (Troops In Contact) so that strike aircraft could be ready on station to come to his defence – according to the investigation report, this created ‘a false sense of urgency’ – and then ‘Troops in Contact’. Yet when the attack helicopters fired their missiles no engagement had taken place and the vehicles were moving away from Khod (indeed, they were further away than when they were first observed). This was (mis)read as ‘tactical maneuvering’.

My first rider is that the process is not invariably the coldly, calculating sequence conjured by the emphasis on metadata and algorithms – what Dan McQuillan calls ‘algorithmic seeing’ – or the shrug-your-shouders attitude of Sparkle. This is why the affective is so important, but it is multidimensional. I doubt that it is only in films like Good Kill (below) or Eye in the Sky that pilots and sensor operators are uncomfortable, even upset at what they do. Not all sensor operators are Brandon Bryant – but they aren’t all Sparkle either.

All commentaries on the Uruzgan strike – including my own – draw attention to how the pilot, sensor operator and mission intelligence coordinator watching the three vehicles from thousands of miles away were predisposed to interpret every action as hostile. The crew was neither dispassionate nor detached; on the contrary, they were eager to move in for the kill. At least some of those in the skies above Uruzgan had a similar view. The lead pilot of the two attack helicopters that carried out the strike was clearly invested in treating the occupants of the vehicles as killable bodies. He had worked with the Special Operations detachment before, knew them very well, and – like the pilot of the Predator – believed they were ‘about to get rolled up and I wanted to go and help them out… [They] were about to get a whole lot of guys in their face.’

Immediately after the strike the Predator crew convinced themselves that the bodies were all men (‘military-aged males’):

08:53 (Safety Observer): Are they wearing burqas?

08:53 (Sensor): That’s what it looks like.

08:53 (Pilot): They were all PIDed as males, though. No females in the group.

08:53 (Sensor): That guy looks like he’s wearing jewelry and stuff like a girl, but he ain’t … if he’s a girl, he’s a big one.

Reassured, the crew relaxed and their conversation became more disparaging:

09:02 (Mission Intelligence Coordinator (MC)): There’s one guy sitting down.

09:02 (Sensor): What you playing with? (Talking to individual on ground.)

09:02 (MC): His bone.

….

09:04 (Sensor): Yeah, see there’s…that guy just sat up.

09:04 (Safety Observer): Yeah.

09:04 (Sensor): So, it looks like those lumps are probably all people.

09:04 (Safety Observer): Yep.

09:04 (MC): I think the most lumps are on the lead vehicle because everybody got… the Hellfire got…

….

09:06 (MC): Is that two? One guy’s tending the other guy?

09:06 (Safety Observer): Looks like it.

09:06 (Sensor): Looks like it, yeah.

09:06 (MC): Self‐Aid Buddy Care to the rescue.

09:06 (Safety Observer): I forget, how do you treat a sucking gut wound?

09:06 (Sensor): Don’t push it back in. Wrap it in a towel. That’ll work.

The corporeality of the victims flickers into view in these exchanges, but in a flippantly anatomical register (‘playing with … his bone’; ‘Don’t push it back in. Wrap it in a towel..’).

But the helicopter pilots reported the possible presence of women, identified only by their brightly coloured dresses, and soon after (at 09:10) the Mission Intelligence Coordinator said he saw ‘Women and children’, which was confirmed by the screeners. The earlier certainty, the desire to kill, gave way to uncertainty, disquiet.

These were not the only eyes in the sky and the sequence was not closed around them. Others watching the video feed – the analysts and screeners at Hurlburt Field in Florida, the staff at the Special Operations Task Force Operations Centre in Kandahar – read the imagery more circumspectly. Many of them were unconvinced that these were killable bodies – when the shift changed in the Operations Centre the Day Battle Captain called in a military lawyer for advice, and the staff agreed to call in another helicopter team to force the vehicles to stop and determine their status and purpose – and many of them were clearly taken aback by the strike. Those military observers who were most affected by the strike were the troops on the ground. The commander who had cleared the attack helicopters to engage was ferried to the scene to conduct a ‘Sensitive Site Exploitation’. What he found, he testified, was ‘horrific’: ‘I was upset physically and emotionally’.

My second rider is that war provides – and also provokes – multiple apprehensions of the injured or dead body. They are not limited to the corpo-reality of a human being and its displacement and dismemberment into what Joe calls ‘carcass’. In the Uruzgan case the process of embodying did not end with the strike and the continued racialization and gendering of its victims by the crew of the Predator described by Lauren.

The Sensitive Site Exploitation – the term was rescinded in June 2010; the US Army now prefers simply ‘site exploitation‘, referring to the systematic search for and collection of ‘information, material, and persons from a designated location and analyzing them to answer information requirements, facilitate subsequent operations, or support criminal prosecution’ – was first and foremost a forensic exercise. Even in death, the bodies were suspicious bodies. A priority was to establish a security perimeter and conduct a search of the site. The troops were looking for survivors but they were also searching for weapons, for evidence that those killed were insurgents and for any intelligence that could be gleaned from their remains and their possessions. This mattered: the basis for the attack had been the prior identification of weapons from the Predator’s video feed and a (highly suspect) inference of hostile intent. But it took three and a half hours for the team to arrive at the engagement site by helicopter, and a naval expert on IEDs and unexploded ordnance who was part of the Special Forces detachment was immediately convinced that the site had been ‘tampered with’. The bodies had been moved, presumably by people from a nearby village who had come to help:

The bodies had been lined up and had been covered… somebody else was on the scene prior to us … The scene was contaminated [sic] before we got there.

He explained to MG Timothy McHale, who lead the subsequent inquiry, what he meant:

The Ground Force Commander reported that he ‘wouldn’t take photos of the KIA [Killed in Action] – but of the strike’, yet it proved impossible to maintain a clinical distinction between them (see the right hand panel below; he also reported finding bodies still trapped in and under the vehicles).

His photographs of the three vehicles were annotated by the investigation team to show points of impact, but the bodies of some of the dead were photographed too. These still photographs presumably also had evidentiary value – though unlike conventional crime scene imagery they were not, so far I can tell, subject to any rigorous analysis. In any case: what evidentiary value? Or, less obliquely, whose crime? Was the disposition of the bodies intended to confirm they had been moved, the scene ‘contaminated’ – the investigator’s comments on the photograph note ‘Bodies from Vehicle Two did not match blast pattern’ – so that any traces of insurgent involvement could have been erased? (There is another story here, because the investigation uncovered evidence that staff in the Operations Centres refused to accept the first reports of civilian casualties, and there is a strong suspicion that initial storyboards were manipulated to conceal that fact). Or do the shattered corpses driven into metal and rock silently confirm the scale of the incident and the seriousness of any violation of the laws of war and the rules of engagement?

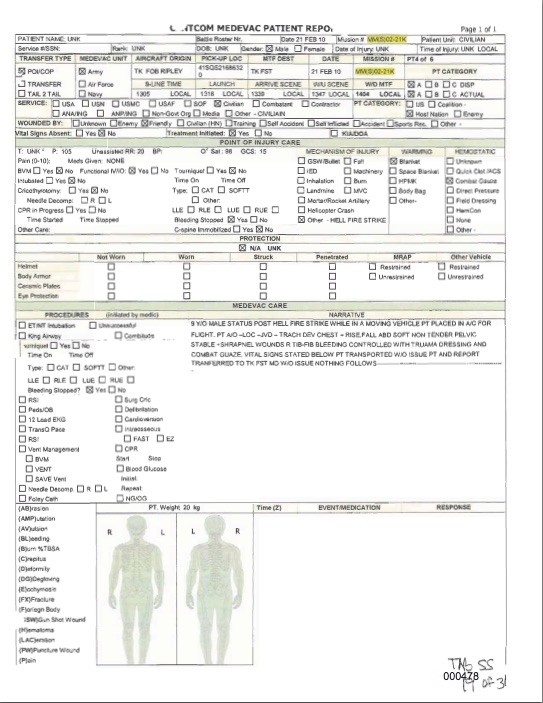

The Ground Force Commander also had his medics treat the surviving casualties, and called in a 9-line request (‘urgent one priority’) for medical evacuation (MEDEVAC). Military helicopters took the injured to US and Dutch military hospitals at Tarin Kowt, and en route they became the objects of a biomedical gaze that rendered their bodies as a series of visible wounds and vital signs that were distributed among the boxes of standard MEDEVAC report forms:

At that stage none of the injured was identified by name (see the first box on the top left); six of the cases – as they had become – were recorded as having been injured by ‘friendly’ forces, but five of them mark ‘wounded by’ as ‘unknown’. Once in hospital they were identified, and the investigation team later visited them and questioned them about the incident and their injuries (which they photographed).

These photographs and forms are dispassionate abstractions of mutilated and pain-bearing bodies, but it would be wrong to conclude from these framings that those producing them – the troops on the ground, the medics and EMTs – were not affected by what they saw.

And it would also be wrong to conclude that military bodies are immune from these framings. Most obviously, these are standard forms used for all MEDEVAC casualties, civilian or military, and all patients are routinely reduced to an object-space (even as they also remain so much more than that: there are multiple, co-existing apprehensions of the human body).

Yet I have in mind something more unsettling. Ken MacLeish reminds us that

Yet I have in mind something more unsettling. Ken MacLeish reminds us that

for the soldier, there is no neat division between what gore might mean for a perpetrator and what it might mean for a victim, because he is both at once. He is stuck in the middle of this relation, because this relation is the empty, undetermined center of the play of sovereign violence: sometimes the terror is meant for the soldier, sometimes he is merely an incidental witness to it, and sometimes he, or his side, is the one responsible for it.

If there is no neat division there is no neat symmetry either; not only is there a spectacular difference between the vulnerability of pilots and sensor operators in the continental United States and their troops on the ground – a distance which I’ve argued intensifies the desire of some remote crews to strike whenever troops are in danger – but there can also be a substantial difference between the treatment of fallen friends and foe: occasional differences in the respect accorded to dead bodies and systematic differences in the (long-term) care of injured ones.

But let’s stay with Ken. He continues:

Soldiers say that a body that has been blown up looks like spaghetti. I heard this again and again – the word conjures texture, sheen, and abject, undifferentiated mass, forms that clump into knots or collapse into loose bits.

He wonders where this comes from:

Does it domesticate the violence and loss? Is it a critique? Gallows humor? Is it a reminder, perhaps, that you are ultimately nothing more than the dumb matter that you eat, made whole and held together only by changeable circumstance? Despite all the armor, the body is open to a hostile world and can collapse into bits in the blink of an eye, at the speed of radio waves, electrons, pressure plate springs, and hot metal. The pasta and red sauce are reminders that nothing is normal and everything has become possible. Some body—one’s own body—has been placed in a position where it is allowed to die. More than this, though, it has been made into a thing…

One soldier described recovering his friend’s body after his tank had been hit by an IED:

… everything above his knees was turned into fucking spaghetti. Whatever was left, it popped the top hatch, where the driver sits, it popped it off and it spewed whatever was left of him all over the front slope. And I don’t know if you know … not too many people get to see a body like that, and it, and it…

We went up there, and I can remember climbing up on the slope, and we were trying to get everybody out, ’cause the tank was on fire and it was smoking. And I kept slipping on – I didn’t know what I was slipping on, ’cause it was all over me, it was real slippery. And we were trying to get the hatch open, to try to get Chris out. My gunner, he reached in, reached in and grabbed, and he pulled hisself back. And he was like, “Holy shit!” I mean, “Holy shit,” that was all he could say. And he had cut his hand. Well, what he cut his hand on was the spinal cord. The spine had poked through his hand and cut his hand on it, ’cause there was pieces of it left in there. And we were trying to get up, and I reached down and pushed my hand down to get up, and I reached up and looked up, and his goddamn eyeball was sitting in my hand. It had splattered all up underneath the turret. It was all over me, it was all over everybody, trying to get him out of there…

I think Ken’s commentary on this passage provides another, compelling perspective on the horror so deeply embedded in Joe’s essay:

There is nothing comic or subversive here; only horror. Even in the middle of the event, it’s insensible, unspeakable: and it, and it …, I didn’t know what I was slipping on. The person is still there, and you have to “get him out of there,” but he’s everywhere and he’s gone at the same time. The whole is gone, and the parts – the eye, the spine, and everything else – aren’t where they should be. A person reduced to a thing: it was slippery, it was all over, that was what we sent home. He wasn’t simply killed; he was literally destroyed. Through a grisly physics, there was somehow less of him than there had been before, transformed from person into dumb and impersonal matter.

‘Gore,’ he concludes, ‘is about the horror of a person being replaced by stuff that just a moment ago was a person.’ Explosive violence ruptures the integrity of the contained body – splattered over rocks or metal surfaces in a catastrophic bioconvergence.

I hope it will be obvious that none of this is intended to substitute any sort of equivalence for the asymmetries that I have emphasised throughout this commentary. I hope, too, that I’ve provided a provisional supplement to some of the current work on metadata, algorithms and aerial violence – hence my title. As Linda McDowell remarked an age ago – in Working Bodies (pp. 223-4) – the term ‘meatspace’ is offensive in all sorts of ways (its origins lie in cyberpunk where it connoted the opposite to cyberspace, but I concede the opposition is too raw). Still, it is surely important to recover the ways in which later modern war and militarised violence (even in its digital incarnations) is indeed obdurately, viscerally offensive – for all of the attempts to efface what Huw Lemmey once called its ‘devastation in meatspace‘.

The Death of the Clinic

This is the fifth in a new series of posts on military violence against hospitals and medical personnel in conflict zones. It follows directly from my analysis of the situation in Syria here.

President Bashar al-Assad has consistently denied that his forces have attacked hospitals or doctors. In an interview with SBS Australia on 1 July 2016 he asked his interviewer:

‘… the very simple question is: why do we attack hospitals and civilians?… No government in this situation has any interest in killing civilians or attacking hospitals. Anyway, if you attack hospitals, you can use any building to be a hospital. No, these are anecdotal claims, mendacious statements …’

There are at least four answers to Assad’s disingenuous question (if you falter at the adjective, see here).

(1) Silencing the witnesses

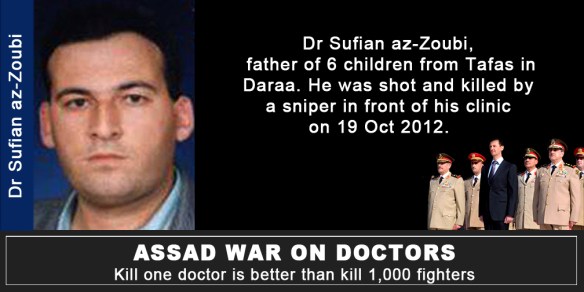

When Widney Brown from Physicians for Human Rights testified at the Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission on 31 March 2016 she provided one clear and compelling rationale for Assad’s attacks on doctors:

‘… attacks on doctors silence particularly powerful witnesses. When the Syrian government denies its use of chemical weapons, cluster munitions, starvation, or torture, doctors can bear witnesses to these violations because they have seen and treated the victims.’

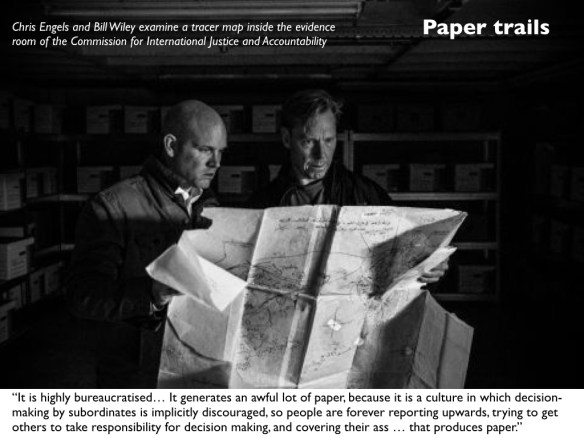

To be sure, there are other witnesses and even paper trails and photographic records. Ben Taub, who has done so much to bring ‘Syria’s war on doctors‘ to the attention of a wider public, has also provided a detailed account of the work done by Bill Wiley and the Commission for International Justice and Accountability whose volunteers have smuggled over 600,000 documents out of Syria detailing mass torture and killings by the regime.

The war crimes have not been confined to attacks on hospitals in opposition-held areas. A photographer known only as ‘Caesar’, who had been attached to the Defence Ministry’s Criminal Forensic Division, smuggled out thousands of high-resolution digital images exposing the horrors of the regime’s own military hospitals:

The pictures, most of them taken in Syrian military hospitals, show corpses photographed at close range – one at a time as well as in small groupings. Virtually all of the bodies – thousands of them – betray signs of torture: gouged eyes; mangled genitals; bruises and dried blood from beatings; acid and electric burns; emaciation; and marks from strangulation…

These unfortunates may have lived and died in different ways, but they were bound in death by coded numerals scribbled on their skin with markers, or on scraps of paper affixed to their bodies. The first set of numbers (for example, 2935 in the photographs at bottom) would denote a prisoner’s I.D. The second (for example, 215) would refer to the intelligence branch responsible for his or her death. Underneath these figures, in many cases, would appear the hospital case-file number (for example, 2487/B)…

[T]he system of organizing and recording the dead served three ends: to satisfy Syrian authorities that executions were carried out; to ensure that no one was improperly discharged; and to allow military judges to represent to families—by producing official-seeming death certificates—that their loved ones had died of natural causes. In many ways, these facilities were ideal for hiding “unwanted” individuals, alive or dead. As part of the Ministry of Defense, the hospitals were already fortified, which made it easy to shield their inner workings and keep away families who might come looking for missing relatives. “These hospitals provide cover for the crimes of the regime,” said Nawaf Fares, a top Syrian diplomat and tribal leader who defected in 2012. “People are brought into the hospitals, and killed, and their deaths are papered over with documentation.” When I asked him, during a recent interview in Dubai, Why involve the hospitals at all?, he leaned forward and said, “Because mass graves have a bad reputation.”

(2) Multiplying the casualties

This is a radicalisation of an old strategy. As Sam Weber pointed out in Targets of opportunity (2005), ‘every target is inscribed in a network or chain of events that inevitably exceeds the opportunity that can be seized or the horizon that can be seen.’ So, for example, when the United States or Israel bombs a power plant it often as not explains that it has been careful to bomb in the small hours when only a skeleton staff was in the building in order to minimise collateral damage. But this begs the question: why bomb the power plant at all? In most instances the degradation of the electricity supply means that it becomes impossible to pump water or treat sewage; refrigerators fail and food perishes; hospitals are forced to use unreliable generators. The result – the intended, carefully calculated result – is that casualties rise at considerable distances from the target and over an extended period of time.

Similarly, Dr Abdulaziz Adel notes: ‘Kill a doctor and you kill thousands.’ Simply put, patients who are sick or injured then go without treatment and in many cases their lives are put at risk. (The images below are from Collateral Damage: more here).

Dr Rami Kalazi, a neurosurgeon from East Aleppo, agrees:

‘They are the artery of life in the city. Can you imagine a life in city without hospitals? Who will treat your kids? Who will make the surgeries for the injured people? So, they are targeting these hospitals because they know, if these hospitals were completely destroyed, the life will be completely destroyed.’

(3) ‘Moral[e] bombing’

This too is an old strategy. The architects of ‘area bombing’ during the combined bomber offensive against Germany during the Second World War described it as ‘moral [sic] bombing’: a sustained and systematic attempt to undermine the morale of the enemy population so that they would demand their leaders sue for peace. If this was a tried and tested strategy, however, the test showed that it was a complete failure (see my ‘Doors into nowhere’: DOWNLOADS tab).

But the lesson was lost in Syria, where attacks on hospitals have had a central place. As Samir Puri argues, the strategy behind the joint Syrian and Russian air campaign seems to be:

“If there is a total collapse of any kind of trauma care, those are the sort of things that can contribute to collapsing morale very suddenly. The morale of a besieged force can look robust until it collapses.”

And Syria is not unique in contemporary wars: Israel has deployed the same strategy in its repeated assaults on Gaza (see here, here and here for ‘Operation Protective Edge’ in 2014), and the Saudi-led coalition has attacked more than 70 hospitals and health facilities in Yemen since March 2015 (in this latter case Russian media have reported MSF’s objections to the ‘utter disregard for civilian life’ without dissent: see for example here).

‘Preventing medicine’, as Annie Sparrow puts it, has become ‘a new weapon of mass destruction’.

(4) ‘Violence legislates’

Following the attack on the UN aid convoy delivering supplies to a Syrian Red Crescent warehouse outside East Aleppo on 19 September 2016, 101 humanitarian organisations issued a joint appeal to the United Nations on 22 September; in part it read:

‘Deliberate attacks on humanitarian workers and civilians are war crimes. This must mark a turning point: the UN Security Council cannot allow increasingly brazen violations of international humanitarian law to continue with impunity.

‘Heads of state are gathered in New York this week for the United Nations General Assembly. Each one that accepts a lack of accountability for perpetrators and facilitators of war crimes colludes in the ongoing dissolution of international humanitarian law’ (my emphases).

The first paragraph is damning enough. Ben Taub in the New Yorker again:

Nowhere has the supposed deterrent of eventual justice proved so visibly ineffective as in Syria. Like most countries, Syria signed the Rome Statute, which, according to U.N. rules, means that it is bound by the “obligation not to defeat the object and purpose of the treaty.” But, because Syria never actually ratified the document, the International Criminal Court has no independent authority to investigate or prosecute crimes that take place within Syrian territory. The U.N. Security Council does have the power to refer jurisdiction to the court, but international criminal justice is a relatively new and fragile endeavor, and, to a disturbing extent, its application is contingent on geopolitics.

But the sting comes in the second paragraph. As I’ve noted before, international humanitarian law is not a neutral court of appeal, a deus ex machina above the fray, but has always been closely entangled with military violence. In many respects it travels in the baggage train, constantly pulled by the trajectory of the very violence it supposedly seeks to regulate (or facilitate, depending on your point of view). In short, as Eyal Weizman has it, ‘violence legislates‘.

There is good reason to fear that the systematic violation of medical neutrality is intended to force its dissolution. Thomas Arcaro writes: ‘Humanitarian principles like neutrality and impartiality that once seemed so self-evident have been drawn into question, especially on the politically and ethnically complex battlefields of Iraq and Syria.’

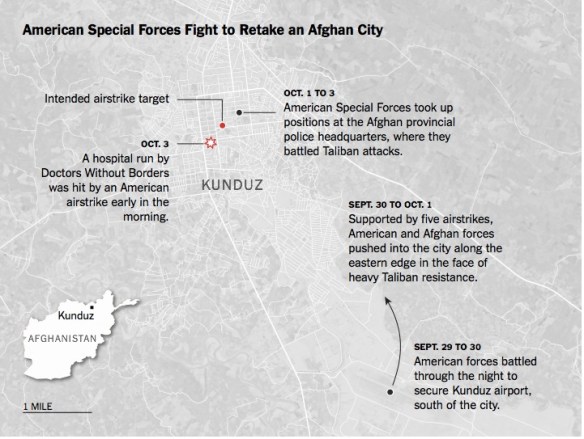

And not only there. In the case of the US airstrike on the MSF Trauma Centre in Kunduz in 2015, I’ve suggested that some key Afghan officers and politicians chafed at the protections afforded to wounded Taliban combatants by international humanitarian law. They also alleged that the Trauma Centre had breached its conditional immunity because the Taliban had overrun the hospital and were firing at US and Afghan forces from its precincts. There is no evidence to support that assertion, but it is an increasingly familiar claim. On 7 December 2016 US Central Command justified a ‘precision strike’ requested by Iraqi forces on a building within the al-Salem hospital complex in Mosul by claiming that IS fighters had used it as a base to launch heavy and sustained machine-gun and rocket-propelled grenade attacks. That would certainly have compromised the hospital’s immunity, but international humanitarian law still requires a warning to be issued before any attack and a proportionality analysis to be conducted; Colonel John Dorrian said that the US Air Force did not ‘have any reason to believe civilians were harmed’ but conceded that it was ‘very difficult to ascertain with full and total fidelity’ whether any medical staff or patients were in the building at the time of the air strike.

But what the Syrian case suggests is a new impatience with medical neutrality tout court: not only a hostility towards the treatment of wounded and sick combatants but also an unwillingness to extend sanctuary to wounded and sick civilians.

And that reluctance is not confined to the Assad regime and its allies. A survey carried out for the International Committee of the Red Cross between June and September makes for alarming reading – even once you’ve overcome your scepticism about public opinion polls. As Spencer Ackerman reports:

Areas in active conflict record greater urgency over questions of civilian protection in wartime than do the great powers that often conduct or participate in those conflicts. In Ukraine, 83% believe everyone wounded and sick during a conflict has a right to health care, compared with 62% of Russians. A full 100% of Yemenis endorse the proposition, as do 81% of Afghans, 66% of Syrians and 42% of Iraqis – compared with 49% of Americans, 53% of Britons, 37% of the Chinese and 67% of the French.

It’s that last clause that is so disturbing: for the last four states listed are all permanent members of the UN Security Council…

So what, then, are we to make of what I’ve been calling ‘the exception to the exception’?

The exception to the exception

I think it’s a mistake to treat ‘the camp’, following Giorgio Agamben‘s vital work, as the exemplary, diagnostic site of the modern space of exception; the killing fields of today’s wars (themselves spaces of indistinction, where it is never clear where war stops and peace begins, where the geometry of the battlefield or, better, ‘battlespace’ becomes ever more fractured and blurred, and where the partitions between international and internal conflicts have been reduced to rubble) are also spaces within which groups of people are deliberately and knowingly exposed to death through the removal of legal protections that would ordinarily be afforded to them. In short, killing and injuring become legally permissible.

I think it’s a mistake to treat ‘the camp’, following Giorgio Agamben‘s vital work, as the exemplary, diagnostic site of the modern space of exception; the killing fields of today’s wars (themselves spaces of indistinction, where it is never clear where war stops and peace begins, where the geometry of the battlefield or, better, ‘battlespace’ becomes ever more fractured and blurred, and where the partitions between international and internal conflicts have been reduced to rubble) are also spaces within which groups of people are deliberately and knowingly exposed to death through the removal of legal protections that would ordinarily be afforded to them. In short, killing and injuring become legally permissible.

Those exposed groups include both combatants and civilians, but their fate is not determined solely by the suspension of national laws (the case that concerns Agamben) because international humanitarian law continues to afford them some minimal protections. One of its central provisions has been medical neutrality: yet if, through its serial violations in Syria and elsewhere, we are witnessing the slow ‘death of the clinic’ – which I treat as a topological figure which extends from the body of the sick or wounded through the evacuation chain to the hospital itself – and the extinction of ‘the exception to the exception’, the clinic as a (conditionally) sacrosanct space – then I think it’s necessary to add further twists to Agamben’s original conception.

As Adia Benton and Sa’ed Ashtan have argued, medical neutrality – the exception to the exception – represents a fraught attempt to restrict the state’s recourse to military violence: it is a limitation on and has now perhaps become even an affront to sovereign power and the state’s insistence that it is ‘the sole arbiter of who can live and who can die’.

Agamben describes the inhabitants of the space of exception as so many homines sacri – where sacer has the double meaning of both ‘sacred’ and ‘accursed’ – and it may be that in today’s killing fields doctors, nurses and healthcare workers are being transformed into new versions of homo sacer: once ‘sacred’ for their selfless devotion to saving lives, they are now ‘accursed’ for their principled dedication to medical neutrality.

Yet the precarity of their existence under conditions of detention and torture, siege and airstrike, has not reduced them to what Agamben calls ‘bare life’. They care – desperately – whether they live or die; they have improvised a series of survival strategies; they have not been silent in the face of almost unspeakable horror; and they have developed new forms of solidarity, support and sociality.

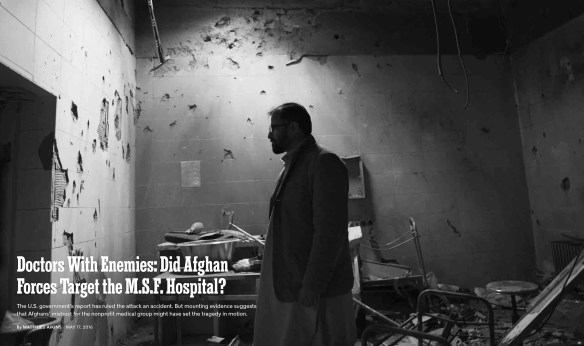

Fighting over Kunduz

This is the third in a new series of posts on military violence against hospitals and medical personnel in conflict zones. It examines some of the key issues arising from the US attack on the Trauma Centre run by Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) in Kunduz on 3 October 2015; it follows directly from my detailed analysis of the attack here and prepares the ground for a still more detailed analysis of attacks on hospitals, doctors and casualties in Syria to follow.

There are at least four main issues arising from the US attack on the MSF Trauma Centre in Kunduz that spiral out into a wider argument about what I will later call ‘The Death of the Clinic’. I’m treating ‘the clinic’ here as a topological figure that extends from the body of the wounded through the evacuation chain to the hospital itself. The clinic has been accorded a privileged status within the space of exception that is the modern conflict zone – a complicated, fractured space in which killing is made permissible subject to the protocols of international humanitarian law – so that the clinic becomes an exception to the exception and its inhabitants granted a conditional immunity from attack.

It’s important to understand that this legal armature is not immutable, and that changes (and challenges) to it arise through both (geo)political and military actions; international humanitarian law is not a deus ex machina, somehow above the fray, but is thoroughly entangled with the prosecution of military violence. More on this to come, but for now it will be enough to list some of the major protections accorded to the clinic in war-time.

The first Geneva Convention (1864) (‘the Red Cross Convention’):

Ambulances and military hospitals shall be acknowledged to be neuter, and, as such, shall be protected and respected by belligerents so long as any sick or wounded may be therein. Such neutrality shall cease if the ambulances or hospitals should be held by a military force … A distinctive and uniform flag shall be adopted for hospitals, ambulances and evacuations.

Under the Hague Regulations (1899/1907) that were in force during the hospital raids in France at the end of the First World War:

… all necessary steps must be taken to spare, as far as possible, … hospitals, and places where the sick and wounded are collected, provided they are not being used at the time for military purposes. It is the duty of the besieged to indicate the presence of such buildings or places by distinctive and visible signs, which shall be notified to the enemy beforehand.

Under the Geneva Conventions (1949) – whose provisions applied to the attack on the MSF Trauma Centre a hundred years later – there is a similar immunity granted to the military-medical machine:

Under the Geneva Conventions (1949) – whose provisions applied to the attack on the MSF Trauma Centre a hundred years later – there is a similar immunity granted to the military-medical machine:

The protection to which fixed establishments and mobile medical units of the Medical Service are entitled shall not cease unless they are used to commit, outside their humanitarian duties, acts harmful to the enemy. Protection may, however, cease only after a due warning has been given, naming, in all appropriate cases, a reasonable time limit and after such warning has remained unheeded.

And this is explicitly extended beyond the military-medical machine to institutions like the MSF Trauma Centre:

Civilian hospitals organized to give care to the wounded and sick, the infirm and maternity cases, may in no circumstances be the object of attack but shall at all times be respected and protected by the Parties to the conflict.

The protection to which civilian hospitals are entitled shall not cease unless they are used to commit, outside their humanitarian duties, acts harmful to the enemy. Protection may, however, cease only after due warning has been given, naming, in all appropriate cases, a reasonable time limit and after such warning has remained unheeded.

In so doing the treatment of hostile combatants is also explicitly provided for and protected:

The fact that sick or wounded members of the armed forces are nursed in these hospitals, or the presence of small arms and ammunition taken from such combatants and not yet been handed to the proper service, shall not be considered to be acts harmful to the enemy.

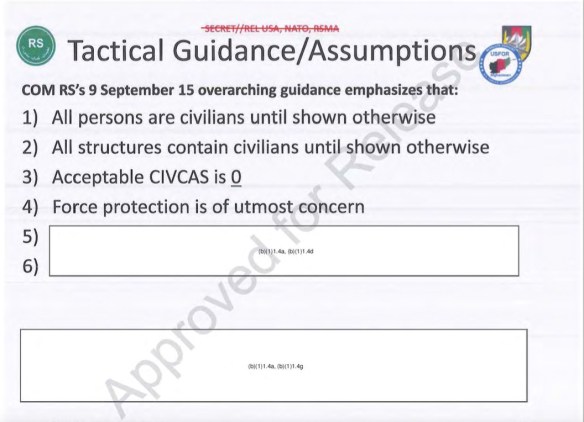

The language and specifications change, but there is nevertheless a consistent thread running through these provisions. It has been stretched – and perhaps broken – by the attack on the MSF Trauma Centre, and here I’ll focus on four issues that have proved contentious. First, the visual identification of the Trauma Centre; second, the alleged breach of its conditional immunity; third, the construal of the attack as a war crime; and fourth, the putative rejection of medical neutrality altogether.

(1) Visual identification

International humanitarian law (IHL) requires those responsible for hospitals ‘to indicate their presence’ – the language varies – in order to ensure their protection, and here the US military investigation made this finding (all page numbers in brackets refer to the redacted report):

The center roof of the MSF Trauma Center was marked with two rectangular MSF flags… The front and sides of the MSF hospital were marked from the street view and a MSF flag flew in the courtyard. The MSF Trauma Center was not marked with any internationally recognized symbols such as a red cross, red crescent or a red “H”. If it had been marked with these symbols, it is possible the Trauma Center would not have been engaged. (082)

This counterfactual does not loom large in the report or its recommendations, but Charles Dunlap (at Lawfire) has seized upon it to berate MSF:

Ask yourself: wasn’t it a mistake for [MSF] – and a serious one – not to have marked its facility in accordance with Protocol III to the Geneva Conventions which designates “the only emblems recognized by nations signifying the protected status of individuals or objects bearing them during armed conflict”? Had, for example, the hospital been marked with large Red Crosses/Red Crescents or one of the other internationally-recognized symbols (as the U.S. does) or something that would make its protected use clear from the air, isn’t it entirely plausible that the aircrew (or someone) might have recognized the error and stopped the attack before it began?

Put another way, isn’t it foreseeable that in an exceptionally chaotic combat situation (where a belligerent is making use of civilian buildings to conduct combat operations) that mistakes could occur in identifying a protected structure absent Protocol III markings or at least something to make it identifiable at a distance, especially when it’s known that attacking aircraft are being used? Wouldn’t reasonably prudent persons have marked their medical facility with an internationally-recognized symbol or something of similar clarity to the warring parties? Wouldn’t due care demand it in that situation?

In accusing MSF of ‘imprudence’ and even recklessness Dunlap applies a double standard. He repeatedly insists that the US and the Afghan militaries confronted ‘an extraordinarily intense situation’ in Kunduz, that they faced ‘terrible urgency’ and ‘enormous pressure’ as they operated ‘in the turmoil of a war zone’ – all of which is undoubtedly true – but he uses this to excuse their mistakes while refusing to extend the same privilege to MSF.

Let me remind you of Dr Kathleen Thomas‘s account of working in the ER (above) once the city had fallen to the Taliban:

The first day was chaos – more than 130 patients poured through our doors in only a few hours. Despite the heroic efforts of all the staff, we were completely overwhelmed. Most patients were civilians, but some were wounded combatants from both sides of the conflict. When I reflect on that day now, what I remember is the smell of blood that permeated through the emergency room, the touch of desperate people pulling at my clothes to get my attention begging me to help their injured loved ones, the wailing, despair and anguish of parents of yet another child lethally injured by a stray bullet whom we could not save, my own sense of panic as another and another and another patient was carried in and laid on the floor of the already packed emergency department, and all the while in the background the tut-tut-tut-tut of machine guns and the occasional large boom from explosions that sounded way too close for comfort.

In any case, MSF had clearly ‘indicated their presence’ to both the US and Afghan authorities by providing them with the GPS co-ordinates of the Trauma Centre (see my previous discussion here). Dunlap finds this ‘commendable’ but ‘legally problematic’.

Instead, he is fixated on the absence of a Red Cross flag from the roof, in which case he might reflect on another passage from the report. On 2 October, the day before the air strike, MSF phoned the Special Operations Task Force in Bagram to develop a contingency plan: while the Taliban were respecting the neutrality of the Trauma Centre and ‘treating the government casualties well’, they wanted to know the feasibility of extracting their patients should conditions deteriorate. During that conversation they were advised to ‘take the signs normally affixed to the sides of the trucks and to install them on the top of the vehicles for easy identification by aircraft during this or any future MSF resupply operations‘ (503; my emphasis). This surely makes it clear that the US military anticipated no difficulty in recognising MSF’s flag and logo as symbols of medical neutrality.

(2) Conditional immunity

IHL makes it clear that treating wounded combatants does not compromise the protections afforded to a medical facility; that occurs only if it is used as a base from which ‘to commit, outside their humanitarian duties, acts harmful to [one of the belligerents]’. I’ll address the intervening clause – ‘outside their humanitarian duties’ – under (4) and confine my discussion here to the alleged militarisation of the clinic.

MSF’s internal review found that its unambiguous ‘no weapons‘ policy was adhered to:

All of the MSF staff reported that the no weapons policy was respected in the Trauma Centre. [Since the KTC opened, there were some rare exceptions when a patient was brought to the hospital in a critical condition and the gate was opened to allow the patient to be delivered to the emergency room without those transporting the patient being first searched. In each of these instances, the breach of the no weapon policy was rapidly rectified.] In the week prior to the airstrikes, the ban of weapons inside the MSF hospital in Kunduz was strictly implemented and controlled at all times and all MSF staff positively reported in their debriefing on the Taliban and Afghan army compliance with the no-weapon policy.

The US military investigation accepted this was indeed the case:

Evidence provided to the investigation team supports the MSF internal initial report’s characterization that their no-weapons policy was adhered to with rare exceptions (038, note 15).

Mathieu Aikins‘s interviewees also confirmed the absence of weapons from the Trauma Centre:

Though the MSF hospital was crowded with fighters, whether patients or caretakers (each patient was allowed one), staff members and civilians who were present said the insurgents respected the rules. They left their weapons outside or handed them over at the gun lockers at the entrance. One employee recalled seeing a fighter give up his weapon but forget his ammunition vest; when the employee nervously approached the fighter about it, the man apologized profusely and handed it over. “We had respect for the hospital, as they were serving the people,” said Shahid, the Taliban commander. “I myself went there once when one of our men was wounded, and before entering we submitted our weapons outside.”

Aikins goes on to report that patients were allowed to retain their cellphones, and some of their caretakers retained hand-held radios whose transmissions were intercepted by Afghan special forces. They in turn concluded that not only were the Taliban inside the hospital but were using it as a base: ‘They had raised their flag and established their headquarters there.’ On 1 October, presumably in response to these reports, the Pentagon contacted MSF in New York to ask whether ‘they had a large number of Taliban “holed up”’ in the Trauma Centre, and were assured that the only Taliban inside the hospital were wounded patients.

But the suspicions clearly remained, and festered to such a degree that some of those on the ground were convinced that the hospital had been overrun by Taliban fighters. Associated Press reported that the radio intercepts prompted US analysts to request ‘specific intelligence-gathering flights over the hospital’ – their outcome has never been disclosed – and on 1 October a senior Special Forces commander (whether in Kabul or in Kunduz is unclear) wrote in his daily log that the Trauma Centre was under Taliban control and that he planned to clear it in the coming days. At least some of the Green Berets in Kunduz agreed with his assessment: ‘They were using it as a C2 node … They had already removed and ransomed the foreign doctors, and they had fired on partnered personnel from there.’ Indeed, after the attack a senior US officer in Kabul was told – by whom has been redacted – that ‘there were three dead Military-Aged Males near the hospital, identified as Taliban by the local population. They were using the hospital as a command post (using its protected status)’ (275).

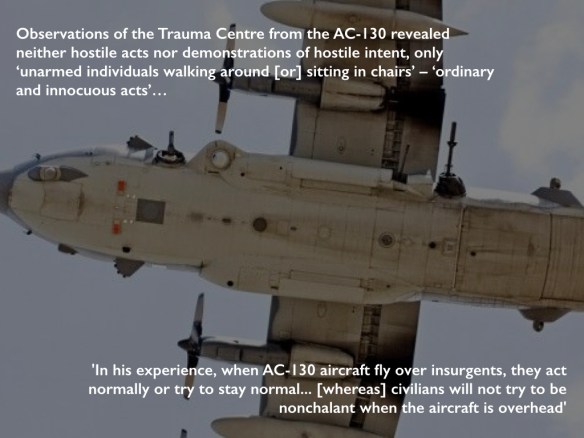

But all of this was fantasy, and the investigation discounted it. Although US intelligence reported that insurgents were present at the hospital at the time of the strike, the investigation accepted that this was for medical treatment and they could trace ‘no specific intelligence reports that confirm[ed] insurgents were using the MSF Trauma Center as an operational C2 [command and control] node, weapons cache or base of operations’ (085). In addition, they determined that observations made from the AC-130 revealed neither substantive hostile acts nor demonstrations of hostile intent – only ‘unarmed individuals walking around [or] sitting in chairs’ (085). The report describes these as ‘ordinary and innocuous acts’ (055), but to at least one member of the aircrew that was in itself grounds for suspicion: ‘In his experience, when AC-130 aircraft fly over insurgents, they act normally or try to stay normal… [whereas] civilians will not try to be nonchalant when the aircraft is overhead’ (093, note 304). Damned if you do, and damned if you don’t: when everything is construed as hostile, even the most innocent acts are transformed into somcething sinister.

The claims made by Afghan forces were even wilder. Here is May Jeong in The Intercept:

On the night of the hospital strike, a unit commander with the Ministry of Defense special forces was at the police headquarters taking fire from the direction of the hospital. “Vehicles were coming out of there, engaging, then retreating,” he told me. When I pointed out that he couldn’t have seen the gate of the hospital from where he was, several hundred meters away, he said that he was sure because he had personally interrogated a cleaner who told him that the hospital was full of “armed men using it as a cover.” The cleaner told the commander that there were Pakistani generals using the hospital as a recollection point and that they had set up a war room there. When I challenged his line of vision again, he responded, “Anyone can claim anything. The truth is different.”

[Amrullah] Saleh, [former head of the National Security Directorate and] the author of the 200-page Afghan commission report on the fall of Kunduz … believed that the “hospital sanctity had been violated” and held out as evidence 130 hours of recorded conversations with more than 600 interlocutors. “I spoke with the MSF country director,” Saleh told me recently. “They don’t deny that the hospital was infiltrated by the Taliban.”

But of course they did deny it: repeatedly, emphatically and convincingly.

(3) War crimes?

The US military investigation was unequivocal: it found multiple violations of the military’s own Rules of Engagement and of international humanitarian law.

The first rule of customary international humanitarian law, now codified in the Additional Protocols to the Geneva Conventions, is distinction:

The parties to the conflict must at all times distinguish between civilians and combatants. Attacks may only be directed against combatants. Attacks must not be directed against civilians.

The investigation found that both the Ground Force Commander (GFC) and the aircraft commander failed to exercise this core principle:

Neither commander distinguished between combatants and civilians nor a military objective and protected property. Each commander had a duty to know, and available resources to know that the targeted compound was protected property’ (075-6).

A second core principle is proportionality:

Launching an attack which may be expected to cause incidental loss of civilian life, injury to civilians, damage to civilian objects, or a combination thereof, which would be excessive in relation to the concrete and direct military advantage anticipated, is prohibited.

The investigation found this to have been disregarded too:

The GFC and the aircraft commander failed to exercise the principle of proportionality in relation to the direct military advantage (076).

Both principles are deceptively simple, and in ‘The Passions of Protection: Sovereign Authority and Humanitarian War’ Anne Orford reminds us that IHL ‘immerses its addressees in a world of military calculations.’ In practical terms the distinction between civilians and combatants in today’s conflicts is rarely straightforward, but in this case the No-Strike List plainly recognised the protected status of the Trauma Centre and there is no convincing evidence that its immunity had been compromised. In addition, the balance between loss of civilian life and military advantage is weighed on the military’s own scales – ‘expected’; ‘excessive’; ‘anticipated’: these are not self-evident calculations – but even if the GFC or the aircraft commander had grounds to believe the Taliban were firing from the hospital the Pentagon’s own Law of War Manual (which is not without its own controversies: see here and, specifically on proportionality, here and here) advises under §7.10.3.2 that

The obligation to refrain from use of force against a medical unit acting in violation of its mission and protected status without due warning does not prohibit the exercise of the right of self-defense. There may be cases in which, in the exercise of the right of self-defense, a warning is not “due” or a reasonable time limit is not appropriate. For example, forces receiving heavy fire from a hospital may exercise their right of self-defense and return fire. Such use of force in self-defense against medical units or facilities must be proportionate.

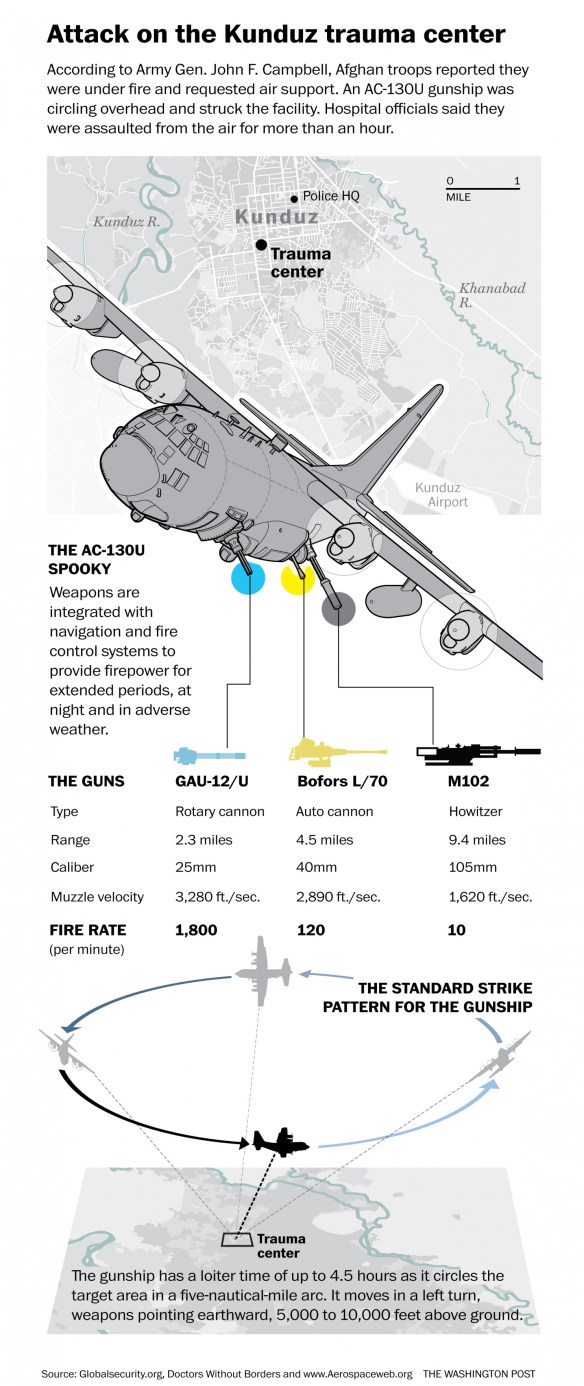

Not only was there was no evidence of hostile let alone ‘heavy fire’ from the Trauma Centre but the AC-130 was also monitoring the progress of the Afghan Special Forces convoy that it was tasked with protecting and knew perfectly well that it was still within the perimeter of the airfield. This was not a time-sensitive target (the report makes that crystal clear) and neither the GFC nor the aircraft commander had reason to believe that any putative threat to Afghan or US forces was so grave and so sustained that it called for an air strike involving multiple passes by the AC-130 – over 30 minutes according to the US military, an hour according to MSF – delivering such intense fires that the building was virtually destroyed.

For these reasons many commentators – and MSF (‘Under the clear presumption that a war crime has been committed, MSF demands that a full and transparent investigation into the event be conducted by an independent international body’) – have insisted that the attack was a war crime.

But others (including the US military) have concluded that it was not. US Central Command’s initial summary – produced before the redacted report was released – accepted that there had been breaches of both the Rules of Engagement and of IHL (‘the law of armed conflict’) but noted that

the investigation did not conclude that these failures amounted to a war crime. The label “war crimes” is typically reserved for intentional acts – intentionally targeting of civilians or intentionally targeting protected objects. The investigation found that the tragic incident resulted from a combination of unintentional human errors, process errors and equipment failures, and that none of the personnel knew that they were striking a medical facility.

The report has been so heavily redacted so that this legal discussion is unavailable (see also the commentary by Sarah Knuckey and two of her students here). We do know that the investigation team included an unnamed legal advisor from US Central Command (CENTCOM) and that its report was subject to legal review by the Staff Judge Advocate, who accepted its findings as ‘legally sufficient’ with several, redacted exceptions – though there is no way of knowing what they were (007-009). We know too that General John Campbell, who ordered the investigation as commander of US Forces in Afghanistan, subsequently disapproved a number of findings and recommendations ‘not related to the proximate cause of the strike’ (002) but, again, the details have been excised.

General Joseph Votel, commander of CENTCOM, repeated the summary statement’s disavowal of war crimes at a Pentagon Press Briefing on 29 April 2016, and in responding to a storm of questions from plainly incredulous reporters (above) he elaborated:

… an unintentional action takes it out of the realm of actually being a deliberate war crime against persons or protected locations…. They were absolutely trying to do the right thing; they were trying to support our Afghan partners; there was no intention on any of their parts to take a short cut, or to violate any rules that were laid out for them. And they were attempting to do the right thing. Unfortunately, they made a wrong judgment in this particular case…

Jens David Ohlin explains the disputation (which Faye Donnelly helpfully re-casts as one between two contending narratives whose speech-acts struggle to realize their performative force):

The problem is that the killing of the innocent civilians was not intentional, it was accidental. As a matter of criminal law, it was either reckless or negligent … but the civilian killings were not performed with purpose.

The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court provides for war crimes prosecutions for ‘intentionally directing’ or ‘intentionally launching’ attacks that contravene international humanitarian law (in effect, criminalizing the rules of IHL). Jens discusses this in relation to attacks on civilians, but the Statute also proscribes ‘intentionally directing attacks against buildings, material, medical units and personnel’ or against ‘personnel, installations, material, units or vehicles involved in a humanitarian assistance or peacekeeping mission’.

In every case the emphasis is on intentionality, and yet intentionality – as philosophers have demonstrated time and time again – is not the simple, settled matter some legal scholars assume it to be. Jens’s central point is that common-law cultures identify intentionality with purpose or knowledge whereas civil-law cultures widen its sphere to include a conscious disregard of risk or ‘recklessness’. The full argument is here – including an intricate disection of the (geo)politics involved in drafting the Geneva Conventions and the Additional Protocols – but the sharp conclusion is that (for Jens, at least) the strike on the Trauma Centre would not constitute a war crime under the first count (he accepts that neither the GFC nor the aircraft commander possessed the knowledge or the purpose) but could under the second (their actions, and those of others, were reckless). I should add that he recommends the recognition of a new war crime to explicitly address the second count and thereby signal ‘the moral difference between intentionally killing civilians and recklessly killing them.’

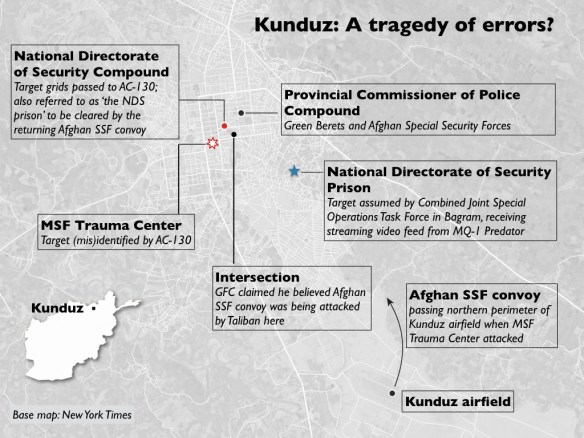

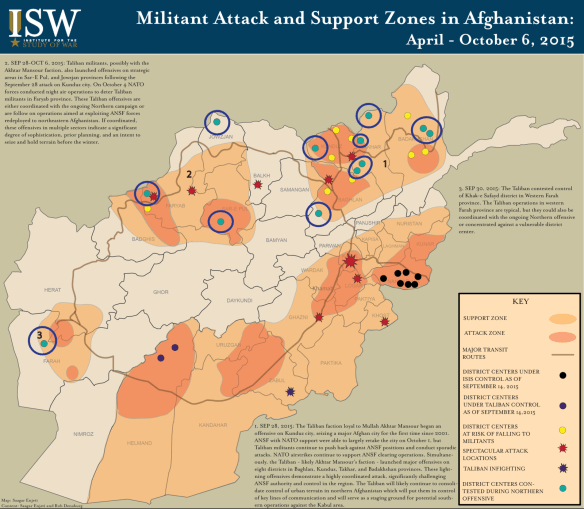

The investigation report provides endless, explicit examples of a thoroughly compromised ‘risk management process’ by multiple actors at multiple sites, and this dispersal of responsibility in Kunduz (see map above) and Bagram further complicates the legal situation. Peter Margulies – who does not accept that ‘the lack of intent among US personnel is determinative’ – concedes that ‘the cascading systemic errors in the hospital attack impede the attribution of culpable awareness to one or more specific individuals.’ In his view,

CENTCOM would have been better served by acknowledging that intent was not required [for the commitment of a war crime], but that awareness of risk was distributed among many organizational components, without full awareness concentrated in one or more individuals who could be charged criminally.

Adil Ahmad Haque notes that Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions requires attackers to do ‘everything feasible’ to verify that their target is a military objective and instructs them in cases of doubt to presume that it is civilian – the Law of War Manual doesn’t follow this standard, but the investigation report does – and here there is such clear evidence of recklessness on the part of many of the US forces involved (whose evidence is shot through with technical failures and radical uncertainty) that, in his view, their decision to press on with the attack ‘was unlawful, irrespective of their good faith.’

(4) Medical neutrality at risk

I noted above that hospitals only lose their protected status if they are used ‘to commit, outside their humanitarian duties, acts harmful to [one of the belligerents]’. It’s a telling provision because its intermediate clause can be read as a tacit acknowledgement that those humanitarian duties – treating the sick and wounded – could otherwise be construed as acts harmful to their enemies.

And there is evidence that this is exactly how both the Afghan government and its military viewed MSF’s activities. When Mathieu Aikins visited Kunduz after the air strike he reported:

Some members of the Afghan government and security forces there had little respect for MSF’s neutrality and resented its treatment of wounded Taliban. When I visited Kunduz in November, their anger was still surprisingly raw, despite the recent destruction of the hospital. “They give them medicine; they transport and treat their injured,” [Colonel Abdullah] Gard, the commander of the [Ministry of Interior’s] quick-reaction force, told me. “Their existence is a big problem for us…. The people that work there are traitors, all of them.”

Gard (seen above) and one of his colleagues told May Jeong exactly the same:

Gard spoke of MSF with the personal hatred reserved for the truly perfidious. He accused the group of “patching up fighters and sending them back out,” a line I heard repeatedly. Cmdr. Abdul Wahab, head of the unit that guarded the provincial chief of police compound, told me he could not understand why in battle an insurgent could be killed, but the minute he was injured, he would be taken to a hospital and given protective status. Wouldn’t it be easier, he asked, wouldn’t the war be less protracted or bloody if they were allowed to march in and take men when they were most compromised? He had visited the MSF hospital three times to complain. Each time a foreign doctor explained the hospital’s neutral status and its no-weapons policy, which mystified him.

In short, it seems that some (perhaps many) in the Afghan security forces – particularly after the humiliation of being forced out of Kunduz – believed that the Taliban were legitimate targets wherever they were and that the fight against them was being hamstrung by what one officer described to Jeong as a ‘silly rule’.