I previously noted the problems of providing medical care to those fleeing the war in Syria – and to those who’ve been left behind – and an article by Thanassis Cambanis in the Boston Globe (‘Medical care is now a tool of war’) reinforces the importance of the issue:

The medical students disappeared on a run to the Aleppo suburbs. It was 2011, the first year of the Syrian uprising, and they were taking bandages and medicine to communities that had rebelled against the brutal Assad regime. A few days later, the students’ bodies, bruised and broken, were dumped on their parents’ doorsteps.

Dr. Fouad M. Fouad, a surgeon and prominent figure in Syrian public health, knew some of the students who had been killed. And he knew what their deaths meant. The laws of war—in which medical personnel are allowed to treat everybody equally, combatants and civilians from any side—no longer applied in Syria.

“The message was clear: Even taking medicine to civilians in opposition areas was a crime,” he recalled.

As the war accelerated, Syria’s medical system was dragged further into the conflict. Government officials ordered Fouad and his colleagues to withhold treatment from people who supported the opposition, even if they weren’t combatants. The regime canceled polio vaccinations in opposition areas, allowing a preventable disease to take hold. And it wasn’t just the regime: Opposition fighters found doctors and their families a soft target for kidnapping; doctors always had some cash and tended not to have special protection like other wealthy Syrians.

Doctors began to flee Syria, Fouad among them. He left for Beirut in 2012. By last year, according to a United Nations working group, the number of doctors in Aleppo, Syria’s largest city, had plummeted from more than 5,000 to just 36.

Since then, Fouad has joined a small but growing group of doctors trying to persuade global policy makers—starting with the world’s public health community—to pay more urgent attention to how profoundly new types of war are transforming medicine and public health.

It is grotesquely ironic that ‘global policy-makers’ should have to be persuaded of the new linkages between war, medicine and public health, given how often later modern war is described (and, by implication, legitimated) through medical metaphors: see in particular Colleen Bell, ‘War and the allegory of medical intervention: why metaphors matter’, International Political Sociology 6: 3 (2012) 325-28 and ‘Hybrid warfare and its metaphors’, Humanity 3 (2) (2012) 225-47.

But there are, as Fouad emphasises, quite other, densely material biopolitics attached to contemporary military and paramilitary violence, including not only the targeting of medical staff, as he says, but also their patients.

But there are, as Fouad emphasises, quite other, densely material biopolitics attached to contemporary military and paramilitary violence, including not only the targeting of medical staff, as he says, but also their patients.

“In Syria today, wounded patients and doctors are pursued and risk torture and arrest at the hands of the security services,” said Marie-Pierre Allié, president of [Médecins san Frontières’]. “Medicine is being used as a weapon of persecution.”

In October 2011 Amnesty International described the partisan abuse of the wounded in hospitals in Damascus and Homs, and the denial of medical care in detention facilities, in chilling detail.

At least then (and there) there were hospitals. Linking only too directly to my previous post on Aleppo, Cambanis concludes:

Today, Fouad’s former home of Aleppo is largely a ghost town, its population displaced to safer parts of Syria or across the border to Turkey and Lebanon. The city’s former residents carry the medical consequences of war to their new homes, Fouad said—not just injuries, but effects as varied as smoking rates, untreated cancer, and scabies. Wars like those in Syria and Iraq don’t follow the old rules, and their effects don’t stop at the border.

I first became aware of these issues at a conference on War and medicine in Paris in December 2012, which prompted my current interest in the casualties of war, combatant and civilian, and the formation of modern medical-military machines. Several friends from the Paris meeting (Omar Dewachi, Vinh-Kim Nguyen and Ghassan Abu Sitta) have since joined with other colleagues to produce a preliminary review published this month in The Lancet: ‘Changing therapeutic geographies of the Iraqi and Syrian wars’. They write:

War is a global health problem. The repercussions of war go beyond death, injury, and morbidity. The effects of war are long term, reshaping the everyday lives and survival of entire populations.

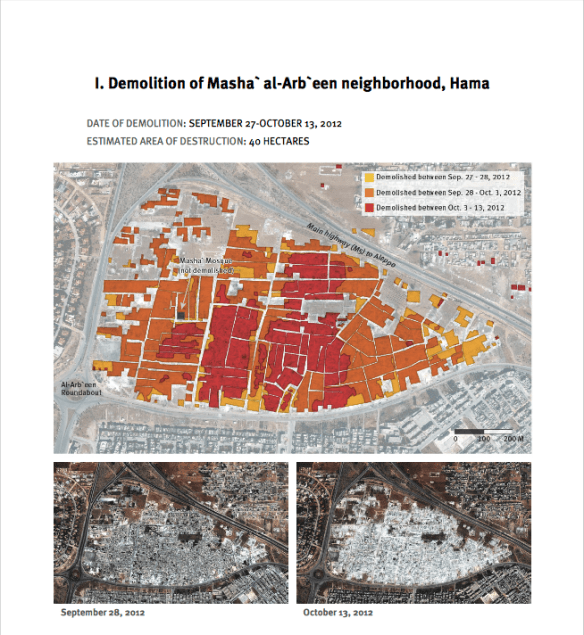

In this report,we assess the long-term and transnational dimensions of two conflicts: the US-led occupation of Iraq in 2003 and the ongoing armed conflict in Syria, which erupted in 2011. Our aim is to show that, although these conflicts differ in their geopolitical contexts and timelines, they share similarities in terms of the effects on health and health care. We analyse the implications of two intertwined processes—the militarisation and regionalisation of health care. In both Syria and Iraq,boundaries between civilian and combatant spaces have been blurred. Consequently,hospitals and clinics are no longer safe havens. The targeting and misappropriation of health-care facilities have become part of the tactics of warfare. Simultaneously, the conflicts in Iraq and Syria have caused large-scale internal and external displacement of populations. This displacement has created huge challenges for neighbouring countries that are struggling to absorb the health-care needs of millions of people.

They emphasise ‘the targeting and implication of medicine in warfare’ and note that ‘the militarisation of health care follows the larger trends of the war on terror, where the boundaries between civilian and combatant spaces are broadly disrespected.’ They have in mind ‘not only the problem of violence against health care, but also [the ways in which] health care itself has become an instrument of violence, with health professionals participating (or being forced to participate) in torture, the withholding of care, or preferential treatment of soldiers.’

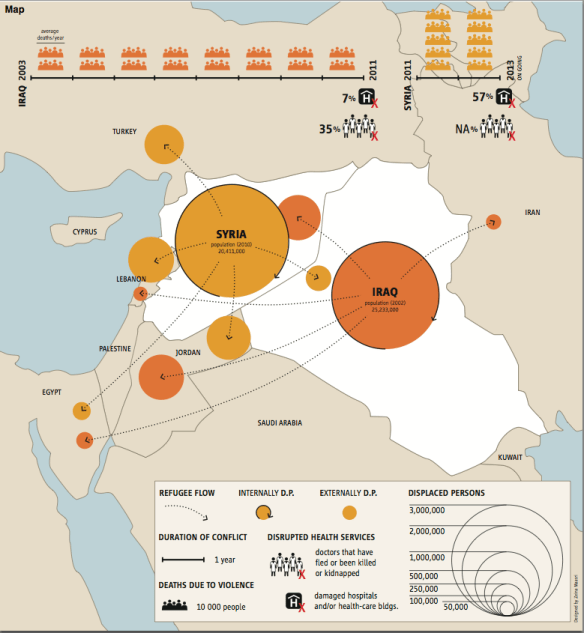

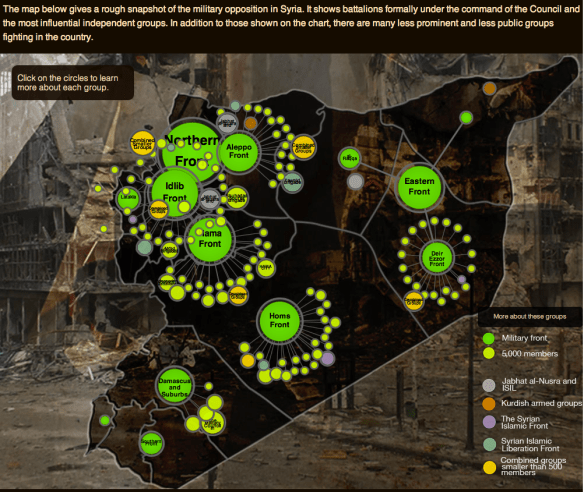

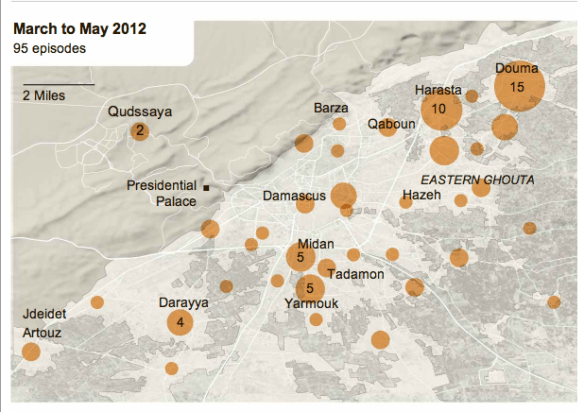

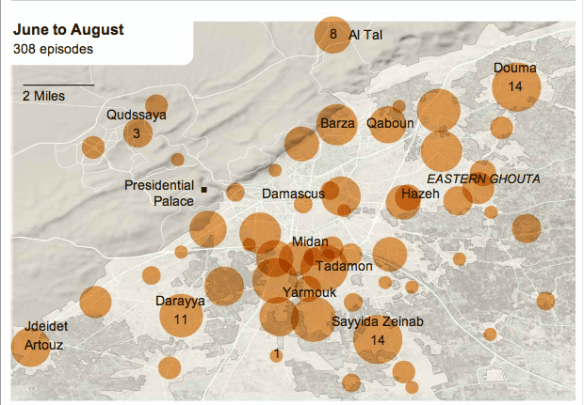

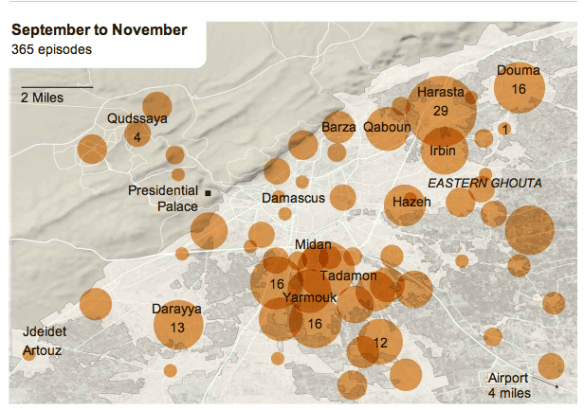

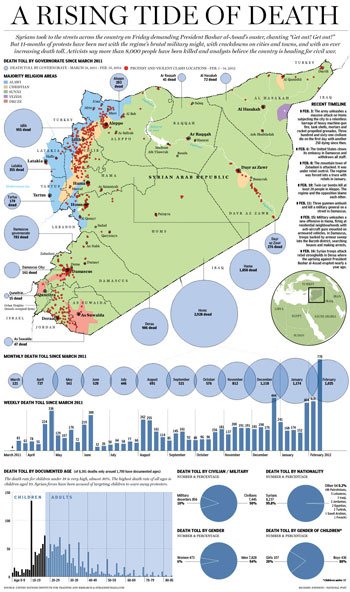

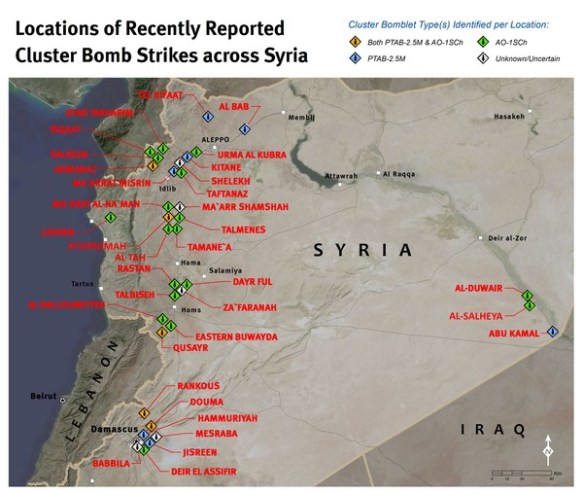

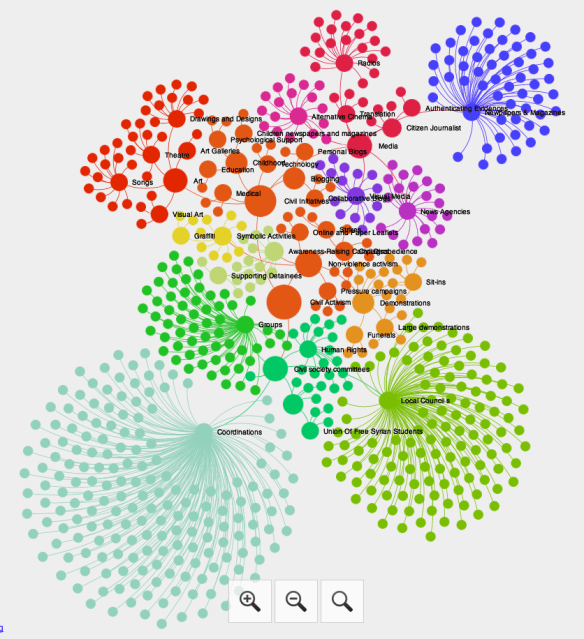

And they describe a largely unplanned dispersal of medical care across the region that blurs other – national – boundaries, requiring careful analysis of the ‘therapeutic geographies‘ which trace the precarious and shifting journeys through which people obtain medical treatment in and beyond the war zone. They insist that ‘migrants seeking refuge from violence cannot be framed and presented as mere victims but as people using various strategies to acquire health care and remake their lives.’ The manuscript version of the report included the map below, which illustrates the scale of the problem:

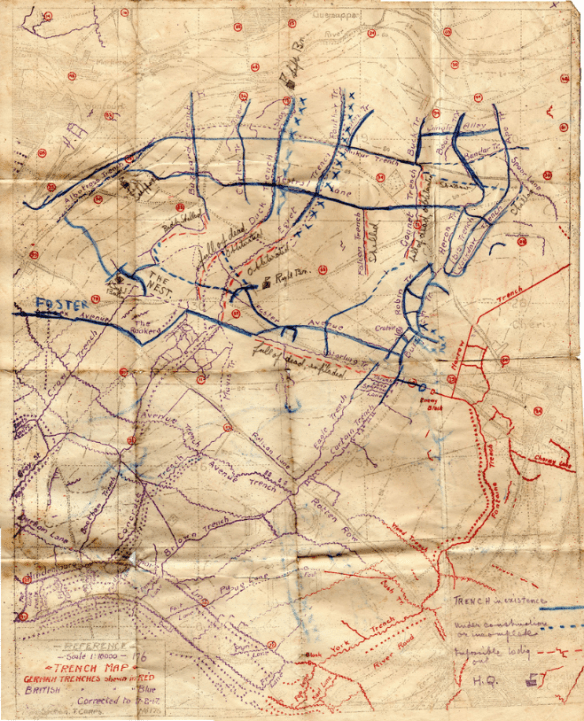

My own work addresses similar issues through four case studies over a longer time-span, to try to capture the dynamics of these medical-military constellations: the Western Front in 1914-18, the Western Desert in the Second World War, Vietnam, and Afghanistan 2001-2014 (see ‘Medical-military machines’, DOWNLOADS tab).

Today Médecins sans Frontières published an important report, Between rhetoric and reality: the ongoing struggle to access healthcare in Afghanistan, that speaks directly to these concerns. Like the Lancet team, the report explores the ways in which war affects not only the provision of healthcare for those wounded by its violences but also access to healthcare for those in the war zone who suffer from other, often chronic and life-threatening illnesses: ‘The conflict creates dramatic barriers that people must overcome to reach basic or life- saving medical assistance. It also directly causes death, injury or suffering that increase medical needs.’ Releasing their findings, MSF explained:

Today Médecins sans Frontières published an important report, Between rhetoric and reality: the ongoing struggle to access healthcare in Afghanistan, that speaks directly to these concerns. Like the Lancet team, the report explores the ways in which war affects not only the provision of healthcare for those wounded by its violences but also access to healthcare for those in the war zone who suffer from other, often chronic and life-threatening illnesses: ‘The conflict creates dramatic barriers that people must overcome to reach basic or life- saving medical assistance. It also directly causes death, injury or suffering that increase medical needs.’ Releasing their findings, MSF explained:

After more than a decade of international aid and investment, access to basic and emergency medical care in Afghanistan remains severely limited and sorely ill-adapted to meet growing needs created by the ongoing conflict… While healthcare is often held up as an achievement of international state-building efforts in Afghanistan, the situation is far from being a simple success story. Although progress has been made in healthcare provision since 2002, the report … reveals the serious and often deadly risks that people are forced to take to seek both basic and emergency care.

The research – conducted over six months in 2013 with more than 800 patients in the hospitals where MSF works in Helmand, Kabul, Khost and Kunduz provinces – makes it clear that the upbeat rhetoric about the gains in healthcare risks overlooking the suffering of Afghans who struggle without access to adequate medical assistance.

“One in every five of the patients we interviewed had a family member or close friend who had died within the last year due to a lack of access to medical care,” said Christopher Stokes, MSF general director. “For those who reached our hospitals, 40 per cent of them told us they faced fighting, landmines, checkpoints or harassment on their journey.”

The patients’ testimonies expose a wide gap between what exists on paper in terms of healthcare and what actually functions. The majority said that they had to bypass their closest public health facility during a recent illness, pushing them to travel greater distances – at significant cost and risk – to seek care.

MSF provides a photoessay describing some of these precarious journeys (‘Long and dangerous roads’) here, from which I’ve taken the photograph below, showing an inured man being led by a relative into the Kunduz Trauma Centre.