There have been many interviews with ‘drone operators’ but most of them seem to have been with sensor operators serving with the US Air Force. Some of the most cited have been ‘whistleblowers’ like Brandon Bryant while some reporters have described conversations with service members allowed to speak on the record during carefully conducted tours of airbases. Some have even been captured on film – think of the interviews that frame so much of Sonia Kennebeck‘s National Bird (though I think the interviews with the survivors of the Uruzgan drone strike are considerably more effective) – while others have been dramatised, notably in Omar Fast‘s 5,000 Feet is The Best.

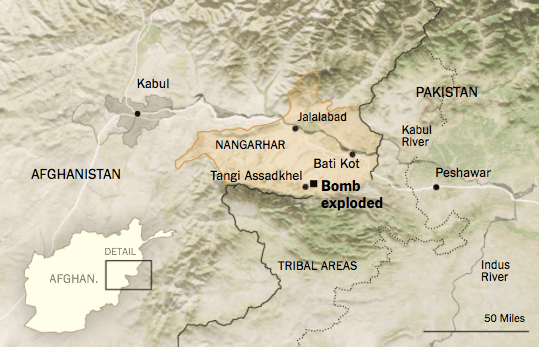

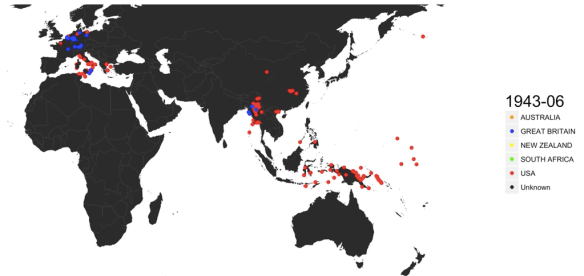

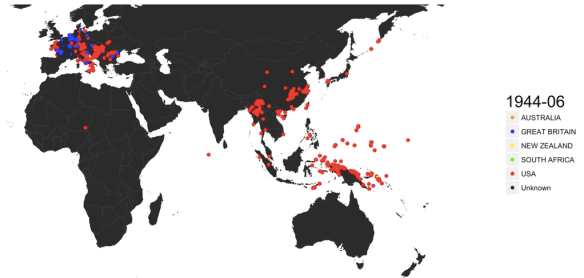

But over at Drone Wars UK Chris Cole has just released something different: a detailed transcript of an extended interview with “Justin Thompson“, a former British (Royal Air Force) pilot who flew Reapers over Afghanistan for three years from Creech Air Force Base in Nevada. He also spent several months forward-deployed to Afghanistan as a member of the Launch and Recovery element: remember that missions are controlled from the continental United States – or now from RAF Waddington in Lincolnshire – but the Reapers have an operational range of 1, 850 km so they have to be launched in or near the theatre of operations.

He served as a pilot of conventional strike aircraft before switching to remote operations early in the program’s development – the RAF started flying Reapers over Afghanistan for ISR in October 2007; armed missions began the following May – which gives Justin considerable insight into the differences between the platforms:

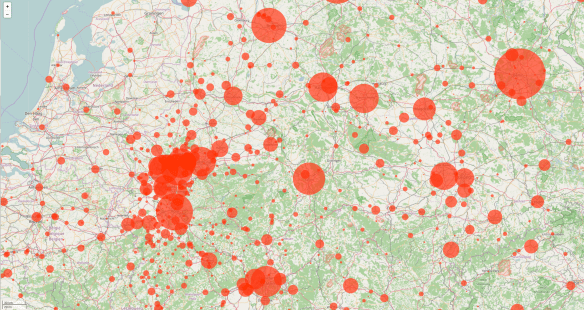

“The real difference with UAVS is persistence. That’s the big advantage as it allows you to build up a very detailed picture of what is going on in a particular area. So if you are in a particular area and a need for kinetic action arises, generally speaking you have already got knowledge of the kind of things you would need to know to assist that to happen. That’s versus a fast jet that might be called in having been there only five minutes, with limited fuel and with limited information – what it can get from the guys on the ground – Boom, bang and he’s off to get some fuel. That’s a bit flippant. It’s not quite like that, but you see what I mean.

“The big difference is the amount of detail we are able to amass about a particular area, not just on one mission, but over time. If you are providing support in a particular area, you develop a great deal of detailed information, to the point where you can recall certain things from memory because you were looking at this last week and spent two weeks previously looking at it and you know generally what goes on in this particular area. The other thing this persistence gives you is a good sense if something has changed or if something is unusual. You go ‘Hang on, that wasn’t there last week, someone’s moved it. Let’s have a look to see what is going on here.’”

Later, having discussed the Reaper’s entanglement of ISR (intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance) with lethal strike (‘kinetic’) capabilities, he returns to the theme:

“If you are talking about kinetic action, I think essentially they [conventional aircraft and drones] are no different. It’s a platform in the air that has a sensor on board you are using to look at the ground. The picture you seen in a [Ground Control Station] is essentially the same as you would see in a fast jet. The sort of weapons you are delivering are exactly the same sort as you would be delivering from a fast jet. Essentially all of the principles are the same…

“A lot of things are significantly better in that you get much more extensive and much more detailed information on the area you are looking at and on any specific targets. That’s not because of any particular capability, it’s just because you can spend a hell of a lot more time looking at it.

“A fast jet pilot would, say, do a four month tour in some place. He’s got four months’ worth of knowledge and then he’ll be gone. He might come back in a year or two, but we are there for three years. Constantly, every day, building up massive amounts of knowledge and a detailed picture of what goes on. We come armed with so much information, and so much information is available to you, not just from your own knowledge, but from sources you can reach out to. You’ve got the text. You’ve got phones. You have got other people you can call on and drag into the GCS. You can get other people to look at the video feed. You can get many opinions and views….”

At times, he concedes, that can become an issue (sometimes called ‘helmet-fire’: too many voices in your head):

“If you want it, there can be a lot of other ‘eyes on’ and advice given to you. If you want something explained to you, if you want a second opinion on something, if you want something checked you can say “Guys, are you seeing this?” Or “What do you think that is?” And that is really useful. You can also reach out for command advice, for legal advice. The number of people who can get a long screwdriver into your GCS is incredible and it does happen that occasionally you have to say ‘Please can you get your long screwdriver out of my GCS’. But generally speaking, it’s well managed and people don’t interfere unless they think there is a reason to.”

He makes it clear that as an RAF pilot his was the final decision about whether to strike – he was ‘the final arbiter’ – and discusses different situations where he over-ruled those other voices.

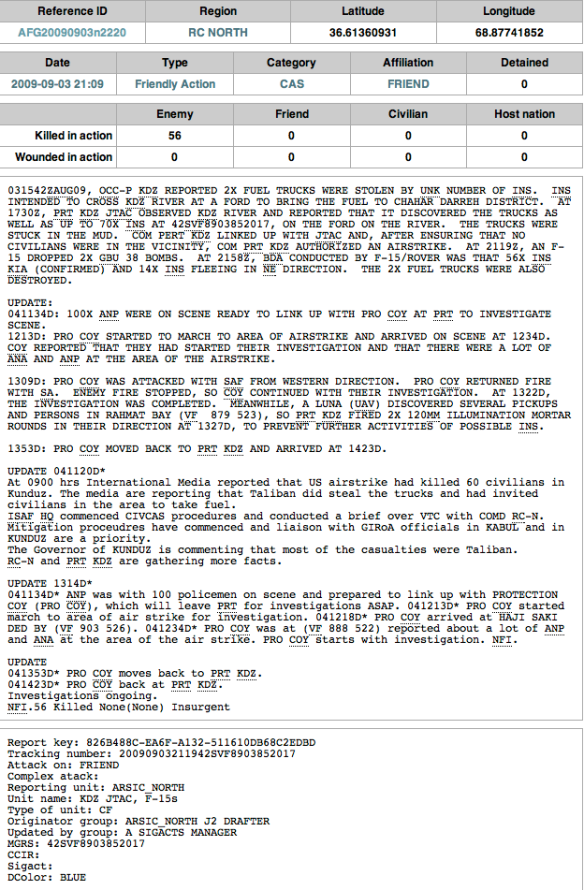

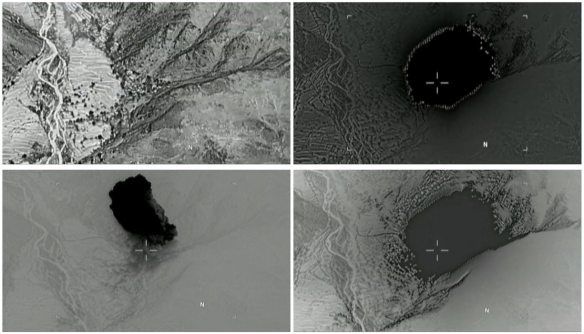

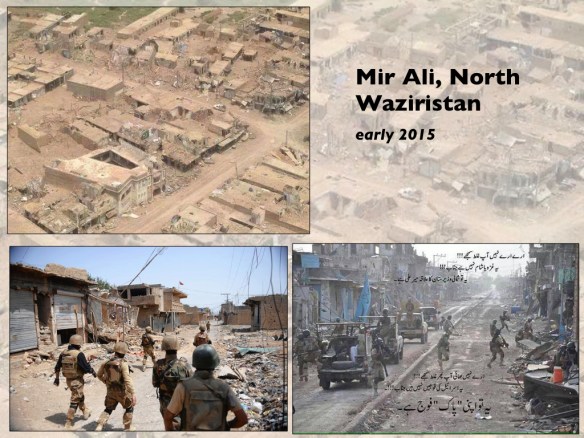

RAF Reaper strike in Afghanistan, 2010

Justin also talks about the ways his previous flying experience modulated his command of the Reaper (and here I think there are interesting parallels with Timothy Cullen‘s experience as an F-16 pilot and his important study of USAF Reaper crews: see also here):

“… [T]here is an idea that because you are not directly manipulating the control surfaces of an aircraft by being sat in it, that somehow lowers the skill level required in order to successfully operate one of these things. It may change some specifics in motor skills, but then so does an Airbus. Conceptually, you are wiggling a stick, pushing a peddle, turning a wheel. That gets converted into little ‘ones’ and ‘zeros’, sent down a wire to a computer that decides where to put the flying control surfaces and throttles the engines of the aircraft. It’s very similar, at least technically, in a modern airliner as in a Reaper. The level of skill required is similar. Piloting has only ever been 10% hand-flying skills, 90% is judgement and airmanship…

“For me, what I was seeing on the screen was very real. In addition to that for me it was more than just two-dimensional. My mind very easily perceived a three-dimensional scene that extended out of the side of the image. Whether that was because I was used to sitting in a cockpit and seeing that sort of picture I don’t know. Someone whose only background is flight simulators or playing computer games may have a different view. I relate it to sitting in an aircraft and flying it, others may relate it slightly differently…”

There’s much more in those packed 17 pages. You can find Chris’s own commentary on the interview here, though his questions during the interview are, as his regular readers would expect, also wonderfully perceptive and well-informed.

One cautionary note. The time-frame is extremely important in commenting on remote operations, even if we limit ourselves to the technology involved. The early Ground Control Stations were markedly different from those in use today, for example, while the quality of the video streams, their compression and resolution is also highly variable. And there is, of course, much more than technology involved.