A characteristically smart post from Larry Lewis at War on the Rocks about Obama’s promise to investigate the mistakes made in the CIA-directed drone strike that unwittingly killed two hostages in Pakistan in January 2015. ‘We’ve been on that path before, in Afghanistan,’ he writes, ‘and we know where it leads: more promises followed by a repeat of similar mistakes.’

Larry explains that the US military was causing an ‘unacceptable number’ of civilian casualties in Afghanistan between 2006 and 2009:

When an incident occurred, they investigated the incident, made changes to guidance, and promised to keep such an incident from happening again. But these incidents kept happening. So the military repeated this ineffective review process again and again. This “repeat” cycle was only broken when military leaders approved the Joint Civilian Casualty Study, a classified outside review requested by General Petraeus. This effort had two key differences from earlier efforts. First, it was independent, so it was able to overcome false assumptions held by operating forces that contributed to their challenges. And second, the study looked at all potential civilian casualty incidents over a period of years, not just the latest incident. This approach helped identify systemic issues with current tactics and policies as the analysis examined the forest and not just the nearest tree. This study also considered different sets of forces operating within Afghanistan and their relative propensity for causing civilian casualties.

You can access the unclassified Executive Summary – co-written by Larry with Sarah Sewell – here. I’ve noted Larry’s important work on civilian casualties before – here, here and here – but his short Op-Ed raises two issues that bear emphasis.

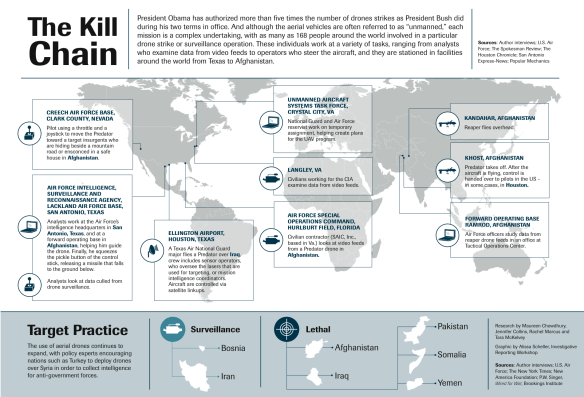

The first is that it is a mistake to abstract strikes carried out by a Predator or a Reaper from air strikes carried out from conventional platforms; the latter are often facilitated and even orchestrated by a UAV – as in the ‘signature’ case of the Uruzgan strike in 2010 – but, pace some drone activists, our central concern should surely be the wider matrix of military violence. This also implies the need to articulate any critique of CIA-directed drone strikes in Pakistan with the use of air power in Afghanistan (and not only because USAF pilots fly the ‘covert’ missions across the border). Here General Stanley McChrystal‘s Tactical Directive issued in July 2009 that directly addressed civilian casualties is a crucial divide. As Chris Woods emphasizes in Sudden Justice,

‘Radically different tactics were now being pursued on either side of the “AfPak” border…. Even as Stanley McChrystal was cutting back on airstrikes in Afghanistan, the CIA was escalating its secret air war in Pakistan’s tribal areas.’

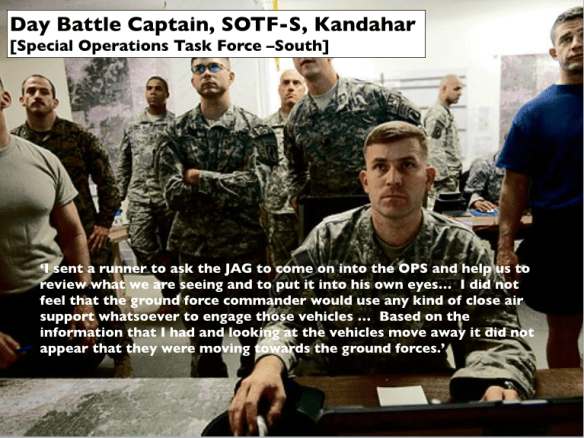

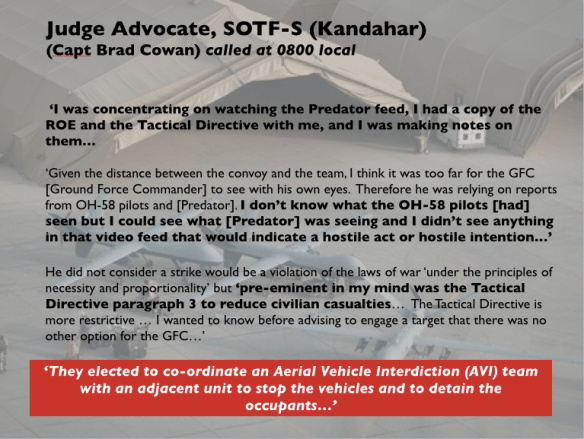

The second issue is the extraordinary partitions – blinkers might be more accurate – that seem to be imposed on military operations and investigations. In the case of the Uruzgan attack, for example, a military lawyer was called in at the eleventh hour to monitor the video feeds from the Predator as it tracked a ‘convoy’ (a term surely as leading as ‘Military-Aged Male’) in the early morning. As the next two slides show, taken from my ‘Angry Eyes’ presentation, the JAG knew the Rules of Engagement (ROE) and the Tactical Directive; he obviously also knew the legal requirements of proportionality, distinction and the rest.

Knowing the ROE, the Tactical Directive and the formal obligations of international law is one thing (or several things): but what about ‘case law’, so to speak? What about knowledge of other, similar incidents that could have informed and even accelerated the decision-making process? In this case, before the alternative course of action could be put into effect and an ‘Aerial Vehicle Interdiction’ set in motion – using helicopters to halt the three vehicles and determine what they were up to – two attack helicopters struck the wholly innocent ‘convoy’ and killed 15-21 civilians. Fast forward to the subsequent, I think forensic Army investigation. This is the most detailed accounting of a ‘CIVCAS’ incident I have read (and you’ll be able to read my analysis of it shortly), and yet here too – even with senior military legal advisers and other ‘subject experts’ on the investigating team – there appears to be no reference to other, similar incidents that could have revealed more of the ‘systemic issues’ to which Larry so cogently refers.

This is made all the stranger because there is no doubt – to me, anyway – that the US military takes the issue of civilian casualties far more seriously than many of its critics allow.