I’ve been scribbling some notes for a short essay Léopold Lambert has invited me to write for his Funambulist Papers. The brief is to write ‘something about the body – nothing too complicated’, so I’ve decided to say something more about the idea of corpography I sketched in ‘Gabriel’s Map’ (DOWNLOADS tab), which will in turn – so I hope – prepare the ground for the long-form version of ‘The nature(s) of war’ for a special issue of Antipode devoted to the work of Neil Smith [next on my to-do list].

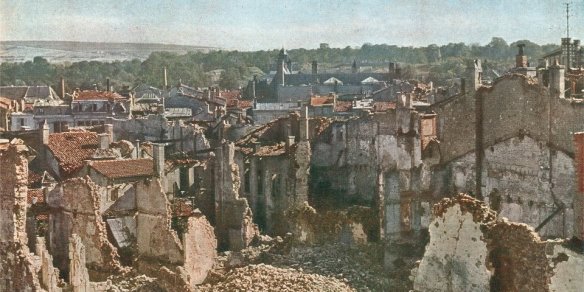

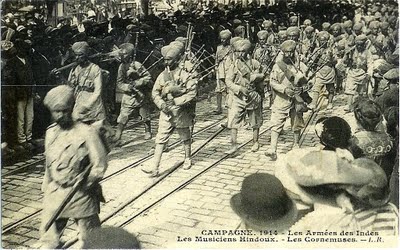

In ‘Gabriel’s Map’ (and in a preliminary sketch here) I contrasted the cartographic imaginary within which so much of the First World War was planned with a corpography improvised by soldiers caught up in the maelstrom of military violence on the ground; unlike the ‘optical war’ that relied, above all, on aerial reconnaissance, projected onto the geometric order of the map and the mechanical cadence of the military timetable – a remarkably abstract space, though its production was of course profoundly embodied – this was a way of apprehending the battle space through the body as an acutely physical field in which the senses of sound, smell and touch were increasingly privileged in the construction of a profoundly haptic or somatic geography.

This is hardly original; you can find intimations of all this in classics like Eric Leed‘s No Man’s Land, and once you start digging in to the accounts left by soldiers you find supporting evidence on page after page. What I’ve tried to do is show that this constituted more than a different way of experiencing war: it was also a different way of knowing and ordering (or, as Allan Pred would surely have said, of re-cognising) the space of military violence. These knowledges were situated and embodied – ‘local’, even – but they were also transmissable and mobile.

On the Western front, corpographies were at once an instinctive, jarring, visceral response to military violence –

‘When sound is translated into a blow on the nape of the neck, and light into a flash so bright that it actually scorches the skin, when feeling is lost in one disintegrating jar of every nerve and fibre … the mind, at such moments, is like a compass when the needle has been jolted from its pivot’ [‘A Corporal’, Field Ambulance Sketches (1919)]

– and an improvisational, learned accommodation to it:

‘We know by the singing of a shell when it is going to drop near us, when it is politic to duck and when one may treat the sound with contempt. We are becoming soldiers. We know the calibres of the shells which are sent over in search of us. The brute that explodes with a crash like that of much crockery being broken, and afterwards makes a “cheering” noise like the distant echoes of a football match, is a five-point-nine.The very sudden brute that you don’t hear until it has passed you, and rushes with the hiss of escaping steam, is a whizz-bang… The funny little chap who goes tonk-phew-bong is a little high-velocity shell which doesn’t do much harm… The thing which, without warning, suddenly utters a hissing sneeze behind us is one of our own trench-mortars. The dull bump which follows, and comes from the middle distance out in front, tells us that the ammunition is “dud.” The German shell which arrives with the sound of a woman with a hare-lip trying to whistle, and makes very little sound when it bursts, almost certainly contains gas.

‘We know when to ignore machine-gun and rifle bullets and when to take an interest in them. A steady phew-phew-phew means that they are not dangerously near. When on the other hand we get a sensation of whips being slashed in our ears we know that it is time to seek the embrace of Mother Earth’ [A.M. Burrage, War is war]

This was not so much a re-setting of the compass, as the anonymous stretcher-bearer had it, as the formation of a different bodily instrument altogether. As Burrage’s last sentence shows, corpographies were at once re-cognitions of a butchered landscape – one that seemed to deny all sense – and reaffirmations of an intimate, intensely sensible bond with the earth:

‘To no man does the earth mean so much as to the soldier. When he presses himself down upon her, long and powerfully, when he buries his face and his limbs deep in her from the fear of death by shell-fire, then she is his only friend, his brother, his mother; he stifles his terror and his cries in her silence and her security…. ’ [Erich Remarque, All quiet on the Western Front]

And corpographies were not only a means through which militarised subjects accommodated themselves to the warscape – providing a repertoire of survival of sorts – but also a way of resisting at least some its impositions and affirming, in the midst of what so many of them insisted was ‘murder not war’, what Santanu Das calls a ‘tactile tenderness’ between men. This, he argues,

‘must be seen as a celebration of life, of young men huddled against long winter nights, rotting corpses, and falling shells. Physical contact was a transmission of the wonderful assurance of being alive, and more sex-specific eroticism, though concomitant, was subsidiary. In a world of visual squalor, little gestures – closing a dead comrade’s eyes, wiping his brow, or holding him in one’s arms – were felt as acts of supreme beauty that made life worth living.’

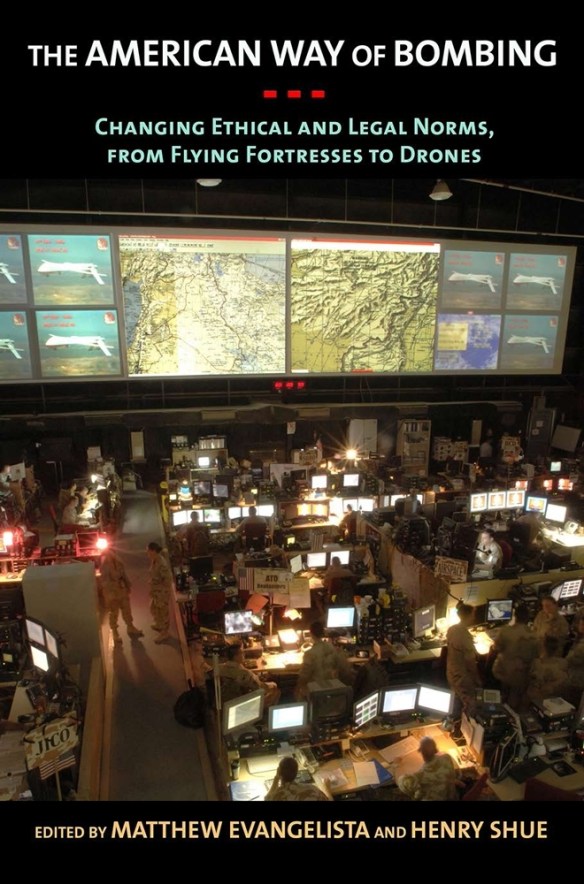

A hundred years later, I have no doubt that much the same is true in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria and elsewhere, and so my interest in corpography is also part of my refusal to acquiesce to the thoroughly disingenuous de-corporealization of today’s ‘virtuous war’.

In fleshing out these ideas I’ve been indebted to a stream of work on the body in human geography. Most of it has been remarkably silent about war, even though Kirsten Simonsen once wrote about ‘the body as battlefield‘, but it’s now difficult for me to read her elegant essay ‘In quest of a new humanism: Embodiment, experience and phenomenology as critical geography’ [Progress in human geography 37 (1) (2013): open access here] – especially Part III where she discusses ‘Thinking the body’ and ‘Orientation and disorientation’ – without peopling it with bodies in khaki, blue or field grey tramping towards the front-line trenches, clambering over the top, or crawling from shell-hole to shell-hole in No Man’s Land.

That is partly down to the suggestiveness of Kirsten’s prose, but it’s also the result of my debt to the work of Santanu Das [Touch and intimacy in First World War literature], Ken MacLeish [especially Chapter 2 of his Making War at Fort Hood; the dissertation version is here] and Kevin McSorley [whose introduction to War and the body is here] which directly addresses military violence. I wish I’d been able to attend the Sensing War conference that Kevin co-organised in London last month; I had to turn down the invitation because I was marooned on my mountaintop in Umbria, but the original Call For Papers captured some of the ways in which the materialities and corporealities of war in the early twentieth century continue to inhabit later modern war:

War is a crucible of sensory experience and its lived affects radically transform ways of being in the world. It is prosecuted, lived and reproduced through a panoply of sensory apprehensions, practices and ‘sensate regimes of war’ (Butler 2012) – from the tightly choreographed rhythms of patrol to the hallucinatory suspicions of night vision; from the ominous mosquito buzz of drones to the invasive scrape of force-feeding tubes; from the remediation of visceral helmetcam footage to the anxious tremors of the IED detector; from the desperate urgencies of triage to the precarious intimacies of care; from the playful grasp of children’s war-toys to the feel of cold sweat on a veteran’s skin.

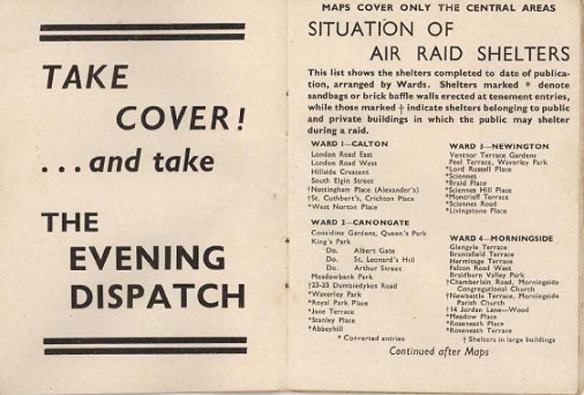

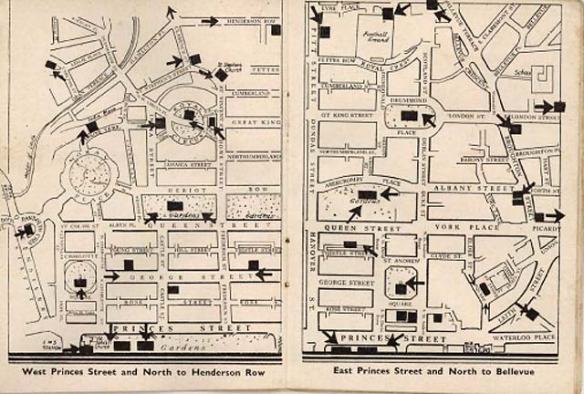

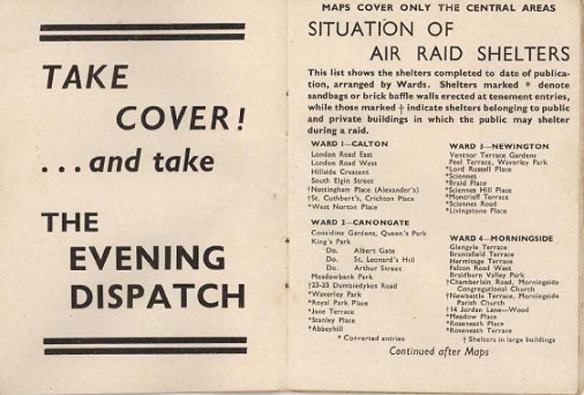

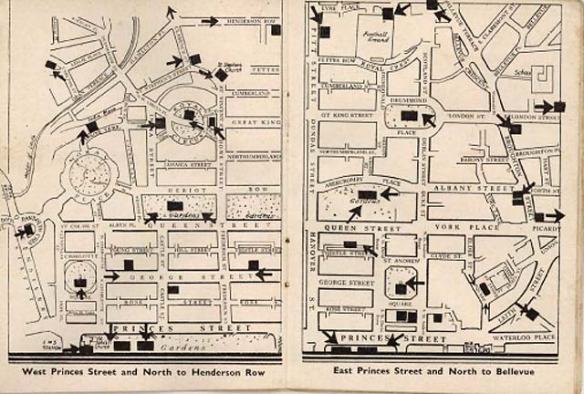

Thus far, like most of the writers I’ve drawn from here, I’ve been thinking about corpographies in relation to the soldier’s body, but as the (in)distinctions between combatant and civilian multiply I’ve started to think about the knowledges that sustain civilians caught up in military and paramilitary violence too. Some of them are undoubtedly cartographic – formal and informal maps of shelters (the images below are for Edinburgh during the Second World War), camps, checkpoints and roadblocks – and some of them rely on visual markers of territory: barriers and wires, posters and graffiti. Today much of this information is shared by social media (as the battle space has become both digital and physical).

But much of this knowledge is also, as it has always been, corpographic. Pete Adey once wrote – beautifully – about what he called ‘the private life of an air raid’, drawing on the files of Mass Observation during the Second World War to sketch a geography of ‘stillness’ even as the urban landscape was being violently ‘un-made’. ‘Stillness in this sense,’ he explained,

‘denotes apprehending and anticipating spaces and events in ways that sees the body enveloped within the movement of the environment around it; bobbing along intensities that course their way through it; positioned towards pasts and futures that make themselves felt, and becoming capable of intense forms of experience and thought.’

This was a corpo-reality, and one in which – as he emphasised – sound played a vital role: ‘Waves of sound disrupted fragile tempers as they passed through the waiting bodies in the physical language of tensed muscles and gritted teeth.’ But, as he also concedes, this was also a ‘not-so private’ life – there was also a social life under the bombs – and we need to think about how these experiences were shared by and with other bodies. These apprehensions of military violence, then as now, were not only modalities of being but also modes of knowing: as Elizabeth Dauphinée suggests, in a different but closely related context, ‘pain is not an invisible interior geography’ but rather ‘a mode of knowing (in) the world – of knowing and making known’ [‘The politics of the body in pain’, Security dialogue 38 (2) (2007) 139-55]. During an air raid these knowledges could be shared by talking with others – the common currency of comfort and despair, advice and rumour – but they also arose from making cognitive sense of physical sensations: the hissing and roaring of the bombs, the suction and compression from the blast, the stench of ruptured gas mains or sewage pipes.

Steven Connor once suggested that air raids involve a ‘grotesquely widened bifurcation of visuality and hearing’, in which the optical-visual production of a target contrasts with ‘the absolute deprivation of sight for the victims of the air raid on the ground, compelled as they are to rely on hearing to give them information about the incoming bombs.’ Those crouching beneath the bombs have ‘to learn new skills of orientating themselves in this deadly auditory field without clear coordinates or dimensions but in which the tiniest variation in pitch and timbre can mean obliteration.’ What then can you know – and how can you know – when your world contracts to a room, a cellar, the space under the bed? When you can’t go near a window in case it shatters and your body is sliced by the splinters? When all you have to go on, all you can trust, are your ears parsing the noise or your fingers scrabbling at the rubble?

Here too none of this is confined to the past, and so I start to think about the thanatosonics of Israel’s air strikes on Gaza. Sound continues to function as sensory assault; here is Mohammed Omer:

‘At just 3 months old, my son Omar cries, swaddled in his crib. It’s dark. The electricity and water are out. My wife frantically tries to comfort him, shield him and assure him as tears stream down her face. This night Omar’s lullaby is Israel’s rendition of Wagner’s Ride of the Valkyries, with F-16s forming the ground-pounding percussion, Hellfire missiles leading the winds and drones representing the string section. All around us crashing bombs from Israeli gunships and ground-based mortars complete the symphony, their sound as distinct as the infamous Wagner tubas…. Above, the ever-present thwup-thwup of hovering Apache helicopters rock Omar’s cradle through vibration. Warning sirens pierce the night—another incoming missile from an Israeli warship.’

And, as before, sound can also be a source of knowledge. Here is Wasseem el Sarraj, writing from Gaza in November 2012:

In our house we have become military experts, specializing in the sounds of Israeli and Palestinian weapons. We can distinguish with ease the sound of Apaches, F-16 missiles, drones, and the Fajr rockets used by Hamas. When Israeli ships shell the coast, it’s a distinct and repetitive thud, marked by a one-second delay between the launch and the impact. The F-16s swoop in like they are tearing open the sky, lock onto their target and with devastating precision destroy entire apartment blocks. Drones: in Gaza, they are called zananas, meaning a bee’s buzz. They are the incessant, irritating creatures. They are not always the harbingers of destruction; instead they remain omnipresent, like patrolling prison guards. Fajr rockets are absolutely terrifying because they sound like incoming rockets. You hear them rarely in Gaza City and thus we often confuse them for low-flying F-16s. It all creates a terrifying soundscape, and at night we lie in our beds hoping that the bombs do not drop on our houses, that glass does not shatter onto our children’s beds. Sometimes, we move from room to room in an attempt to feel some sense of safety. The reality is that there is no escape, neither inside the house nor from the confines of Gaza.

The last haunting sentences are a stark reminder that knowledge, cartographic or corpographic, is no guarantee of safety. But military and paramilitary violence is always more than a mark on a map or a trace on a screen, and the ability to re-cognise its more-than-optical dimensions can be a vital means of navigating the wastelands of war. As in the past, so today rescue from the rubble often involves a heightened sense of sound and smell, and survival is often immeasurably enhanced by the reassuring touch of another’s body. And these fleshy affordances – which you can find in accounts of air raids from Guernica to Gaza – are also a powerful locus for critique.

So: corpographies. I thought I’d made the word up, but as I completed ‘Gabriel’s Map’ I discovered that Joseph Pugliese uses ‘geocorpographies’ to designate ‘the violent enmeshment of the flesh and blood of the body within the geopolitics of war and empire’ in his State violence and the execution of law (New York: Routledge, 2013; p. 86). This complements my own study, though I’ve used the term to confront the optical privileges of cartography through an appeal to the corporeal (and to the corpses of those who were killed in the names of war and empire).

And I’ve since discovered that the term has a longer history and multiple meanings that intersect, in various ways, with what I’m trying to work out. Perhaps not surprisingly, it also serves as a medical term: cranio-corpography is a procedure devised by Claus-Frenzen Claussen in 1968 to capture in a visual trace the longitudinal and lateral movements of a patient’s body in order to detect and calibrate disorders of the ‘equilibrium function’. More recently, corpography has also been used by dance theorists and practitioners, including Francesca Cataldi and Sebastian Prantl, to describe a critical, creative practice: a ‘dance of things’ in which the body is thoroughly immersed as a’ land.body.scape’, as Prantl puts it. Meanwhile, Allan Parsons has proposed a ‘psycho-corpography’ – explicitly not a psycho-geography – as a way of ‘tracing the experience of living-a-body’. Elsewhere, Alex Chase attends to specific bodies-in-the-world, those of cultural ‘figures’ (Artaud, Bataille, Foucault, Genet, Jarman and Mishima among them), that resist normalization – hence emphatically ‘queer’ bodies – and which figure bodies as events. ‘I hope to develop a methodology of “corpography”,’ he says, ‘which would write between biography and textual analysis, material lived bodies and fictional work, life and representation, in order to work through other queer concepts such as temporality, space, and ethics.’

It would of course be absurd to summon all of these different usages onto a single conceptual terrain. But they do take me back to Kirsten’s essay (and to long-ago memories of an enthralling seminar in Roskilde which she introduced through her dance teacher), to ways of apprehending the danse macabre on the Western Front as both a cartography and a corpography whose junction was to be found, perhaps, in a choreography, and to think about the ways in which the sentient bodies of soldiers were at once habituated to and resisted the forceful normalizations of military violence. They also make me wonder about civilian corpographies – about the multiple ways in which violence is inflicted on the body and yet may be resisted through the body – and in doing so they direct my steps from the past to the present and to the fragile bodies that continue to lie at the heart of today’s conflicts. If that is to speak with Walter Benjamin, I want to insist that the ‘tiny, fragile human body’ does not only lie ‘in a field of force of destructive torrents and explosions’, as he wrote in 1936: for the body is a vector as well as a victim of military and paramilitary violence. And it can also be a means of undoing its effects.

I suspect that these ideas will eventually thread their way into my new project on the evacuation of combatant and civilian casualties (and the sick) from war zones, 1914-2014, where it’s already clear to me that cartography and corpography are tightly locked together. All of this is highly provisional, as you’ll realise, and as always I would welcome comments and suggestions.