Just released: a joint investigation by Amnesty International and Forensic Architecture reconstructs Israel’s siege of Rafah during its assault on Gaza in 2014. You can read the Executive Summary here and access the full report, Black Friday: carnage in Rafah, here.

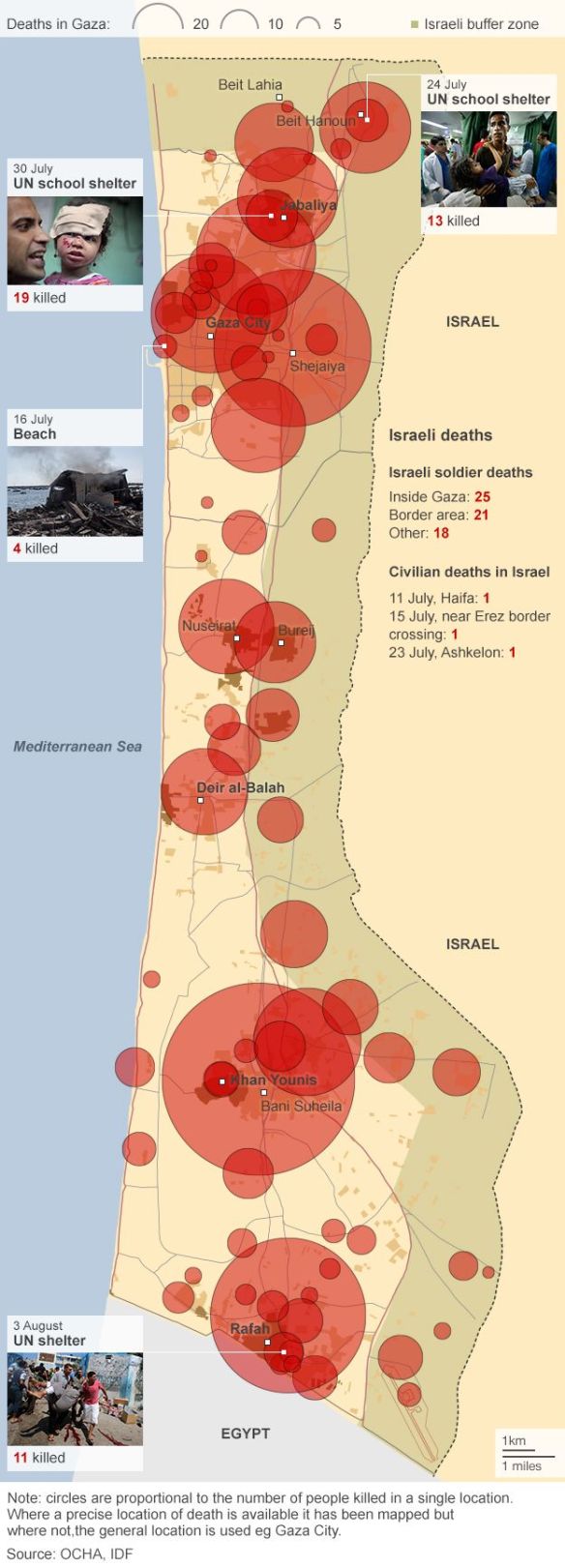

In Rafah, the southernmost city in the Gaza Strip, a group of Israeli soldiers patrolling an agricultural area west of the border encountered a group of Hamas fighters posted there. A fire fight ensued, resulting in the death of two Israeli soldiers and one Palestinian fighter. The Hamas fighters captured an Israeli officer, Lieutenant Hadar Goldin, and took him into a tunnel. What followed became one of the deadliest episodes of the war; an intensive use of firepower by Israel, which lasted four days and killed scores of civilians (reports range from at least 135 to over 200), injured many more and destroyed or damaged hundreds of homes and other civilian structures, mostly on 1 August.

In this report, Amnesty International and Forensic Architecture, a research team based at Goldsmiths, University of London, provide a detailed reconstruction of the events in Rafah from 1 August until 4 August 2014, when a ceasefire came into effect. The report examines the Israeli army’s response to the capture of Lieutenant Hadar Goldin and its implementation of the Hannibal Directive – a controversial command designed to deal with captures of soldiers by unleashing massive firepower on persons, vehicles and buildings in the vicinity of the attack, despite the risk to civilians and the captured soldier(s).

The report recounts events by connecting various forms of information including: testimonies from victims and witnesses including medics, journalists, and human rights defenders in Rafah; reports by human rights and other organizations; news and media feeds, public statements and other information from Israeli and Palestinian official sources; and videos and photographs collected on the ground and from the media.

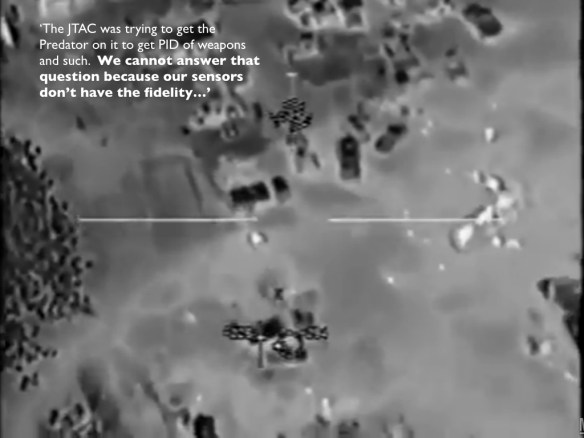

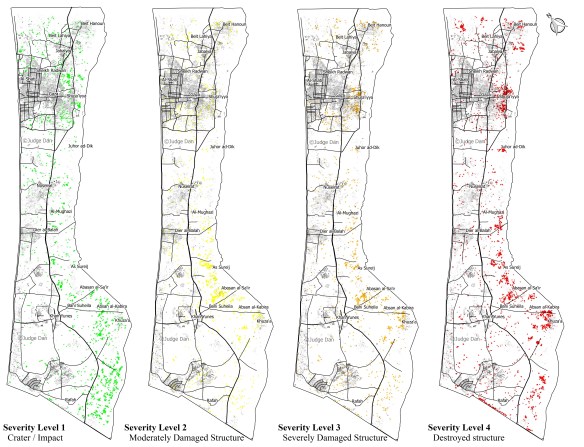

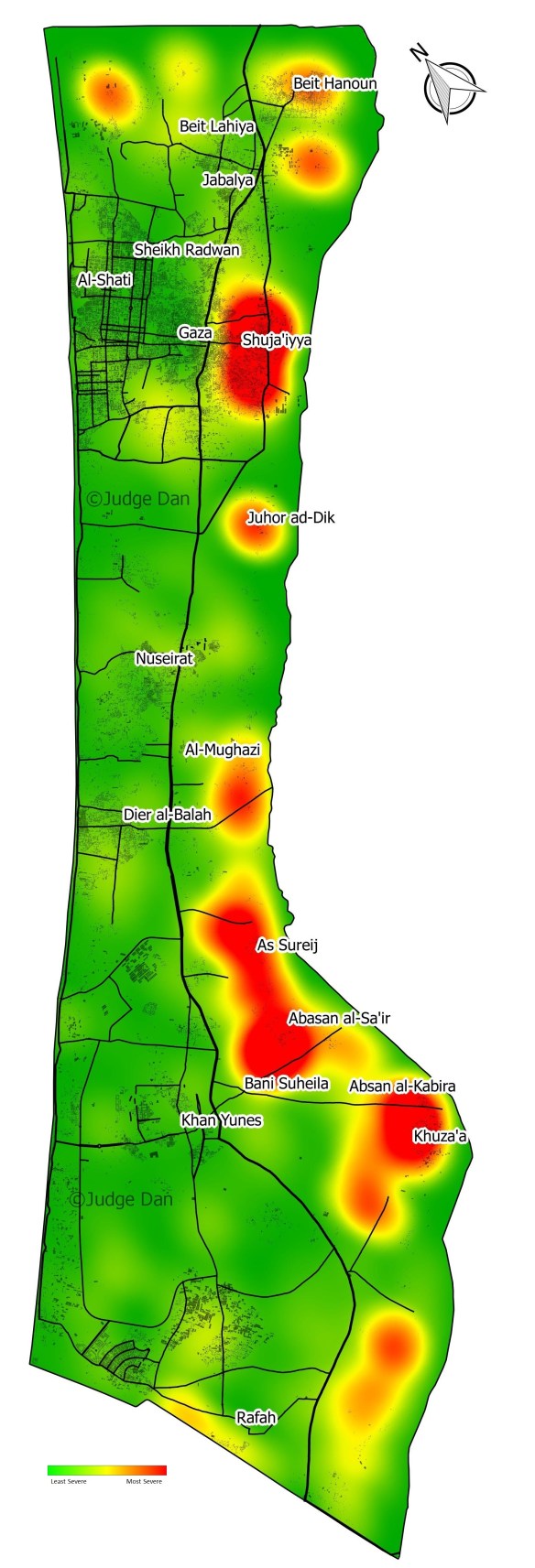

Amnesty International and Forensic Architecture worked with a number of field researchers and photographers who documented sites where incidents took place using protocols for forensic photography. Forensic Architecture located elements of witness testimonies in space and time and plotted the movement of witnesses through a three-dimensional model of urban spaces. It also modelled and animated the testimony of several witnesses, combining spatial information obtained from separate testimonies and other sources in order to reconstruct incidents. Three satellite images of the area, dated 30 July, 1 August and 14 August, were obtained and analysed in detail; the image of 1 August reveals a rare overview of a moment within the conflict. Forensic Architecture also retrieved a large amount of audiovisual material on social media and employed digital maps and models to locate evidence such as oral description, photography, video and satellite imagery in space and time. When audiovisual material from social media came with inadequate metadata, Forensic Architecture used time indicators in the image, such as shadow and smoke plumes analysis, to locate sources in space and time….

Public statements by Israeli army commanders and soldiers after the conflict provide compelling reasons to conclude that some attacks that killed civilians and destroyed homes and property were intentionally carried out and motivated by a desire for revenge – to teach a lesson to, or punish, the population of Rafah for the capture of Lieutenant Goldin.

There is consequently strong evidence that many such attacks in Rafah between 1 and 4 August were serious violations of international humanitarian law and constituted grave breaches of the Fourth Geneva Convention or other war crimes.

It really is worth accessing the full report and closely examining the video animations produced by Forensic Architecture.

You can find a commentary on the project and its wider implications, which also draws on a lecture FA’s Eyal Weizman gave at Médecins sans Frontières in Paris earlier this month, by Léopold Lambert over at Warscapes here: ‘The Hannibal Directive and the economy of lives: making sense of Black Friday in Gaza‘.

The Hannibal Directive exists because of the historical asymmetrical characteristics of prisoner exchanges between the Israeli government and Palestinian and Lebanese political groups like Hamas and Hezbollah. The armed sections of these groups evidently rely on this precise asymmetrical relationship and undertake kidnappings of one or multiple Israeli soldiers when possible to negotiate the liberation of several Palestinians held in Israeli prisons. However, the economy of lives that can be perceived through this asymmetry is profoundly disturbing. The hidden message in the enunciation of the 2011 Shalit exchange is the following: One Israeli life is worth 1,027 Palestinian lives. The very fact that many of us know Shalit’s name, but not one of the 1,027 liberated Palestinian prisoners’, is symptomatic. In the case of “Black Friday,” this economy of lives exposes its violence through even more extreme and perverse forms: for the Israeli army, 135 to 200 Palestinian lives are worth ending in order to end an Israeli one, so to avoid freeing Palestinian prisoners.

We should not think of the concept of economy of lives as a retrospective reading of the Israeli Army’s crimes: This logic is at work in most Western military decision making, as Weizman shows in his book The Least of All Possible Evils (Verso 2011) through interviews with Human Rights Watch consultant Marc Garlasco, a former Pentagon “chief of high-value targeting” during the first years of the 2003 US war in Iraq. For each airstrike against an Iraqi political or military figure that Garlasco designed, he had to follow a “correct balance of civilian casualties in relation to the military value of a mission. ” In other words, there is a number of civilians the US army allows itself to kill as “collateral damage” when targeting a strategic assassination. In Iraq, this number was 30, Garlasco reveals. “In this system of calculation,” writes Weizman, “twenty-nine deaths designates a threshold. Above it, in the eyes of the US military lawyers, is potentially ‘unlawful killing’; below it, ‘necessary sacrifice.’” Here, again, lives are disincarnated into statistics calculated in relation to military and ideological objectives.

I should not that there are also important critiques of Amnesty’s other investigations into ‘Operation Protective Edge’, most significantly from Normal Finkelstein at Jadaliyya.

I should not that there are also important critiques of Amnesty’s other investigations into ‘Operation Protective Edge’, most significantly from Normal Finkelstein at Jadaliyya.

He takes particular exception to Amnesty’s Unlawful and Deadly: Rocket and mortar attacks by Palestinian armed groups during the 2014 Gaza/Israel conflict.

He insists that Amnesty too often cites official Israeli sources in ways that ‘magnify Hamas’s and diminish Israel’s criminal culpability’. You can access what he describes as his ‘forensic analysis’ of that report in two parts, here and here.

My own posts on ‘Operation Protective Edge’ are here, here, here, here, here (my own attempt at a forensic analysis of sorts), and here.